Identification of Workplace Bullying: Reliability and Validity of Indonesian Version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Workplace Bullying

1.2. Prevalence of Workplace Bullying

1.3. Impact of Workplace Bullying

1.4. Workplace Bullying Assessment

1.5. Present Study

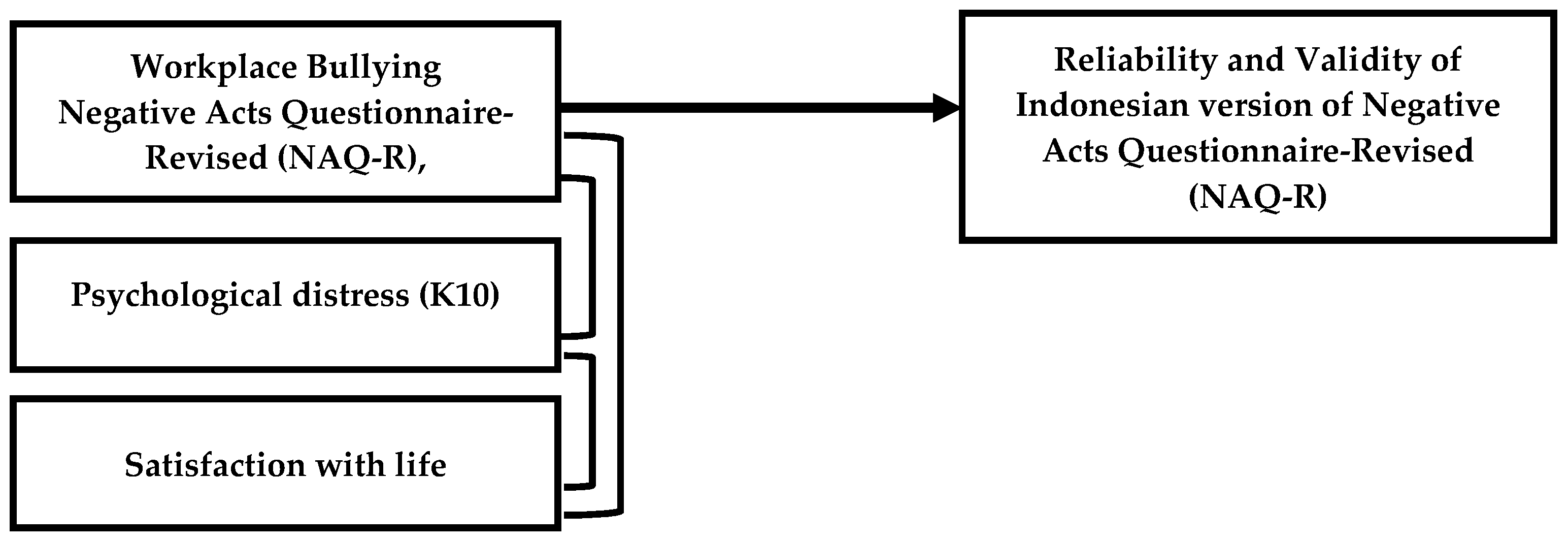

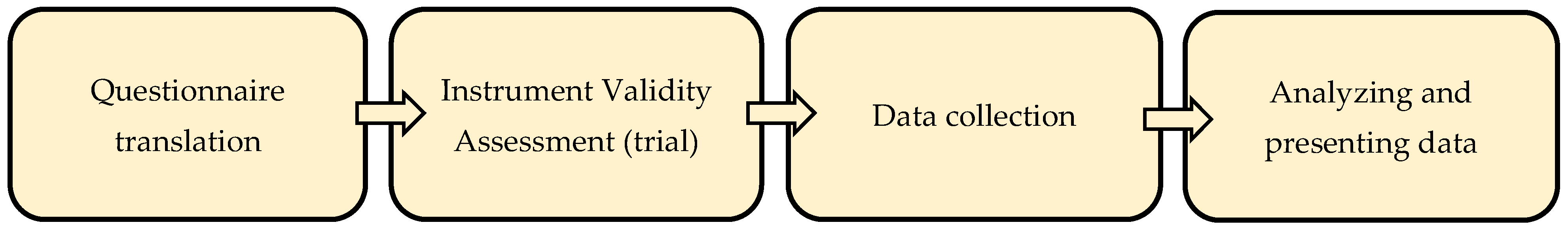

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subject Participants

2.2. Methods

2.3. Instrument

2.3.1. Indonesian Version of NAQ-R

2.3.2. Psychosocial Distress

2.3.3. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants

3.2. Reliability Analysis of the Indonesian Version of NAQ-R

3.3. Factor Structure of the Indonesian Version of NAQ-R

3.4. Concurrent and Constructive Validity of Indonesian NAQ-R

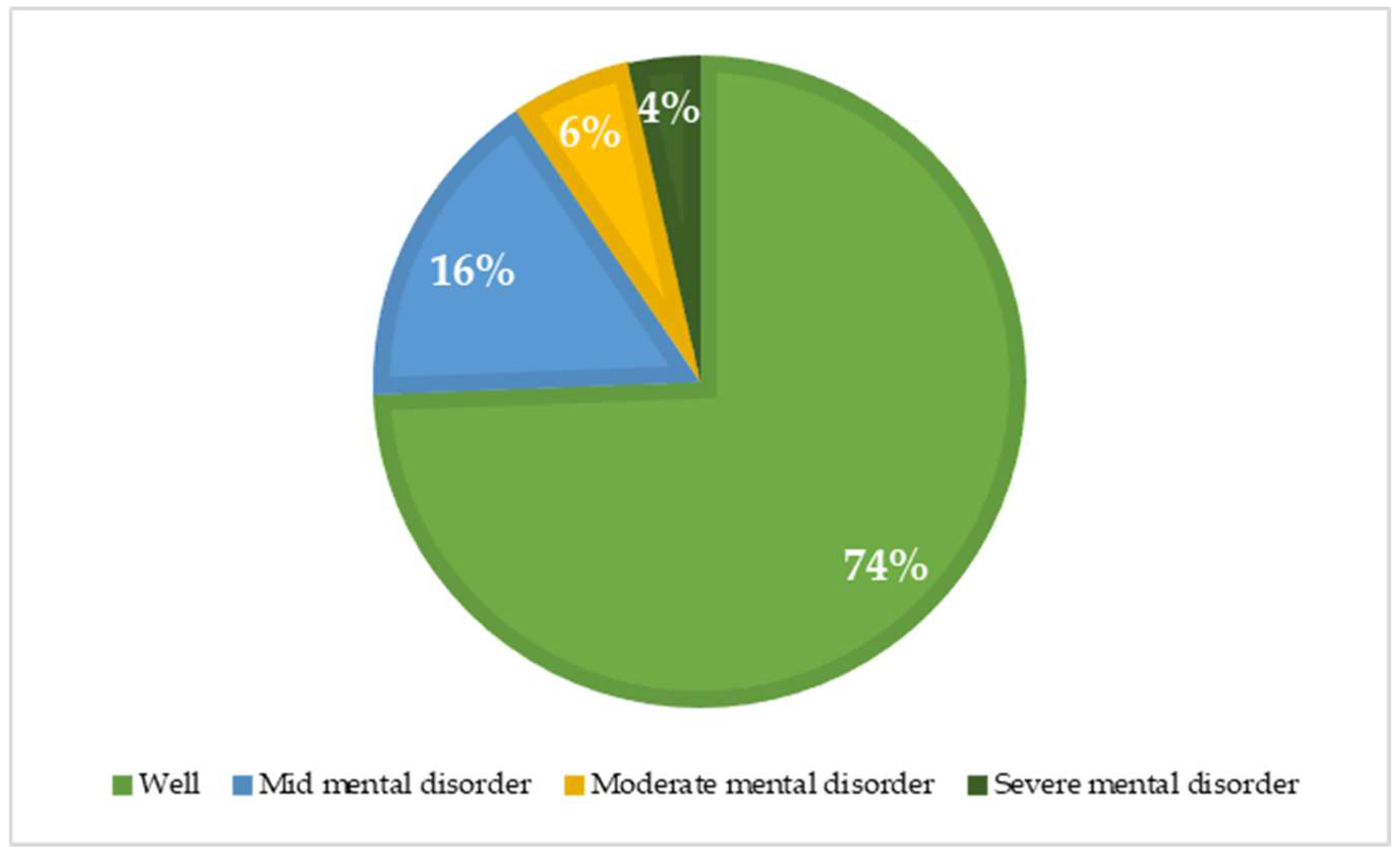

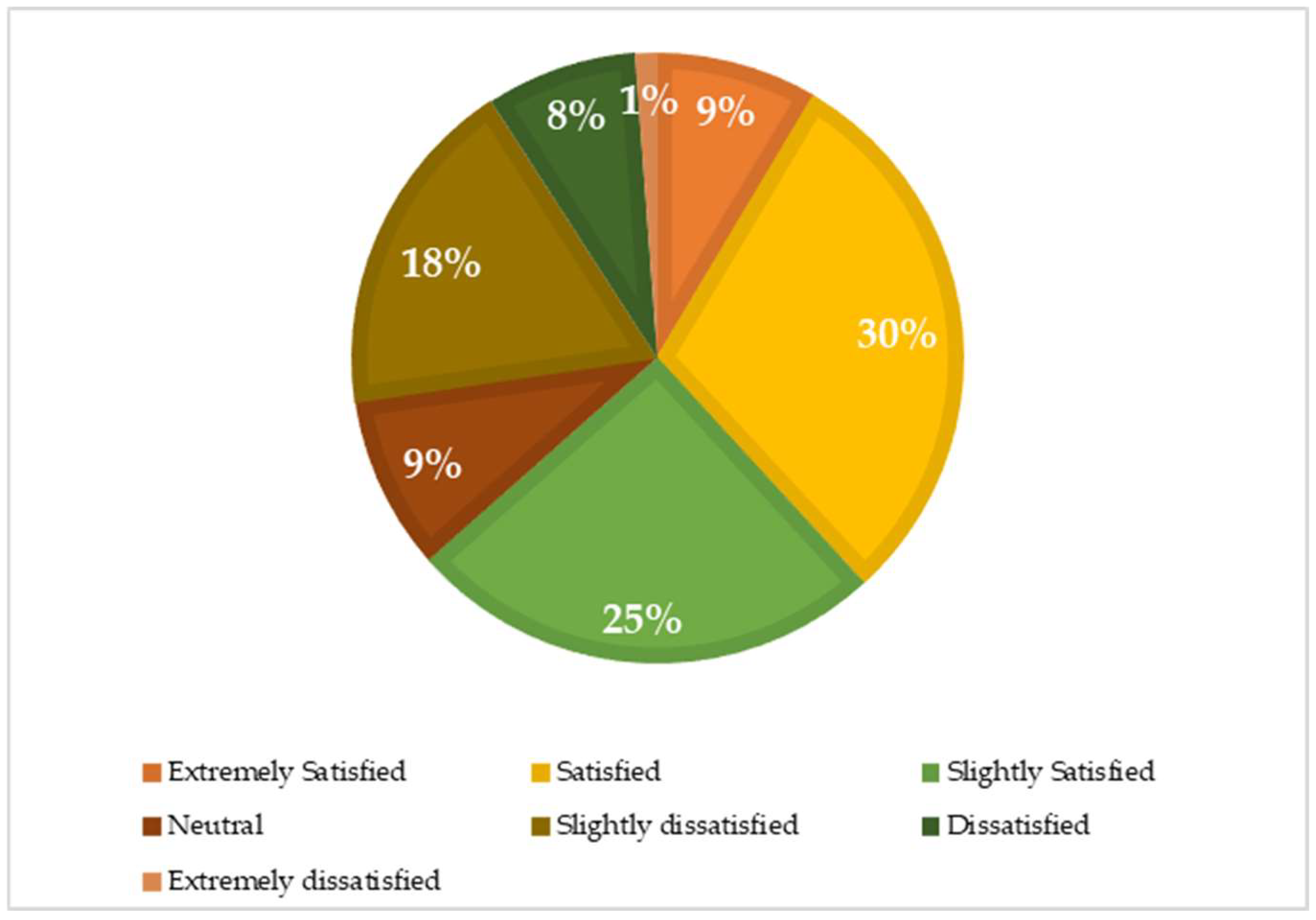

3.5. The Prevalence of Workplace Bullying, Psychosocial Distress, and Satisfaction with Life

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

|

- Tidak Pernah

- Kadang-kadang

- Setiap Bulan

- Setiap Minggu

- Setiap Hari

| No. | Pernyataan | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Seseorang menahan informasi yang mempengaruhi ke kinerja Saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. | Saya dipermalukan atau ditertawakan karena hal yang berkaitan dengan pekerjaan saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. | Saya diperintahkan untuk melakukan pekerjaan dibawah tingkat kompetensi Saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. | Tanggung jawab utama Saya dihilangkan atau diganti dengan tugas yang lebih remeh/tidak penting/rendah/tidak menyenangkan | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5. | Ada yang menyebarkan gosip dan desas desus tentang saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. | Saya diabaikan atau dikucilkan (dianggap tidak ada) di lingkungan kerja saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7. | Saya dihina atau menerima kata-kata kasar tentang diri saya (misalnya tentang kebiasaan dan latar belakang saya, sikap, atau kehidupan pribadi saya) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8. | Saya dibentak atau menjadi target kemarahan spontan (atau amukan spontan) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9. | Saya menerima perlakuan yang intimidatif seperti ditunjuk-tunjuk, pelanggaran ruang pribadi/privasi, didorong, dihambat/dihalangi saat berjalan | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10. | Saya menerima kata-kata sindiran atau tanda-tanda dari rekan lain bahwa saya seharusnya mengundurkan diri dari pekerjaan saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11. | Saya terus menerus diingatkan pada kesalahan dan kelalaian saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12. | Saya diabaikan atau menerima reaksi yang tidak bersahabat ketika saya mendekati seseorang | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 13. | Saya terus menerus menerima kritikan terkait pekerjaan dan usaha saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 14. | Pendapat dan pandangan saya tidak didengar | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 15. | Saya menjadi korban lelucon orang-orang yang tidak cocok dengan saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 16. | Saya diberi tugas dengan target atau tenggat waktu yang tidak masuk akal | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 17. | Saya pernah dituduh berbuat salah atau ilegal tanpa bukti | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 18. | Saya diawasi secara berlebihan di tempat kerja saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 19. | Saya tidak diperbolehkan untuk mengambil apa yang menjadi hak saya di tempat kerja (misalnya cuti sakit, hak libur, biaya perjalanan) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 20. | Saya menjadi target ejekan dan sindirian sindiran kasar (sarcasm) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 21. | Saya diberi beban kerja yang tidak mungkin dapat saya kelola | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 22. | Saya menerima ancaman kekerasan atau pelecehan secara fisik atau verbal/ujaran (perkataan) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 23. | Apakah Anda pernah mengalami perundungan di tempat kerja? Kami mendefinisikan perundungan sebagai suatu situasi ketika seseorang atau beberapa orang secara terus-menerus mempersepsikan dirinya menerima tindakan negatif dari satu orang atau lebih selama suatu jangka waktu tertentu dalam situasi ketika korban perundungan merasa tidak berdaya untuk membela dirinya terhadap Tindakan tersebut. Jika hanya terjadi satu kali, maka kami tidak akan menganggapnya sebagai perundungan. Dengan menggunakan definisi di atas, mohon jawab apakah Anda pernah mengalami perundungan (bully) di tempat kerja selama enam bulan terakhir?

| |||||

| 24. | Jika Anda menjawab“Ya”pada pertanyaan sebelumnya, mohon beri tanda centang pada kotak yang sesuai untuk pernyataansiapa saja yang melalukan perundunganterhadap Anda. (Jawaban boleh lebih dari satu)

| |||||

| 25. | Sebutkan jumlah pelaku atau orang yang melakukan perundungan terhadap Anda. Pelaku laki-laki.: __________________________________ Pelaku Perempuan: __________________________________ | |||||

|

- Tidak pernah

- Jarang

- Kadang-kadang

- Hampir setiap saat

- Setiap saat

| A. | merasa sangat lelah tanpa alasan yang kuat? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| B. | merasa gugup/cemas? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| C. | merasa sangat gugup/cemas sampai-sampai tidak ada sesuatupun yang bisa menenangkan Anda? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| D. | merasa putus asa/tidak ada harapan ? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| E. | merasa gelisah atau resah? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| F. | merasa sangat gelisah sampai-sampai Anda tidak bisa duduk dengan tenang? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| G. | merasa tertekan? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| H. | merasa sangat tertekan sampai-sampai tidak ada yang dapat membuat Anda ceria/terhibur? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I. | merasakan bahwa semua yang diinginkan membutuhkan usaha keras? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| J. | merasa tidak berguna? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

- (1)

- Sedikit lebih jarang dari biasanya

- (2)

- Agak lebih jarang dari biasanya

- (3)

- Sangat lebih jarang dari biasanya

- (4)

- Hampir sama seperti biasanya

- (5)

- Sedikit lebih sering dari biasanya

- (6)

- Agak lebih sering dari biasanya

- (7)

- Sangat lebih sering dari biasanya

- Tidak pernah

- Jarang

- Kadang-kadang

- Hampir setiap saat

- Setiap saat

|

| No. | Pernyataan | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Dalam banyak hal, hidup saya hampir sesuai dengan keinginan saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 2. | Kondisi hidup saya sangat baik | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 3. | Saya merasa puas dengan hidup saya | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 4. | Sejauh ini, saya mendapatkan hal-hal penting yang sesuai dengan keinginan saya dalam hidup | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 5. | Walaupun saya dapat mengulang waktu hidup saya kembali, saya tidak akan merubah apapun yang telah terjadi. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Copyright©2021: |

| Dadan Erwandi, Abdul Kadir, Fatma Lestari |

| Occupational Health and Safety Department, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia, Depok West Java 16424, Indonesia; dadan@ui.ac.id (D.E.), abdul_kadir@ui.ac.id (A.K.), fatma@ui.ac.id (F.L.) |

References

- Volk, A.A.; Dane, A.V.; Marini, Z.A. What Is Bullying? A Theoretical Redefinition. Dev. Rev. 2014, 34, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, M. Stigma Is the Origin of Bullying. J. Cathol. Educ. 2016, 19, 166–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarem, N.N.; Tavitian-Elmadjian, L.R.; Brome, D.; Hamadeh, G.N.; Einarsen, S. Assessment of Workplace Bullying: Reliability and Validity of an Arabic Version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R). BMJ Open 2018, 8, e024009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuno, K.; Kawakami, N.; Inoue, A.; Abe, K. Measuring Workplace Bullying: Reliability and Validity of the Japanese Version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire. J. Occup. Health 2010, 52, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonald, D.N.; Brown, E.D.; Smith, K.F.; Street, S.J. Workplace Bullying: A Review of Its Impact on Businesses, Employees, and the Law. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- D’cruz, P. Depersonalized Bullying at Work from Evidence to Conceptualization; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hoel, H.; Cooper, C.L.; Faragher, B. The Experience of Bullying in Great Britain: The Impact of Organizational Status. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 443–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.V.; Aquino, E.M.L.; Matos Pinto, I.C. Psychometric Properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire for the Detection of Workplace Bullying: An Evaluation of the Instrument with a Sample of State Health Care Workers. Rev. Bras. Saude Ocup. 2017, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.; Bakhshi, A.; Einarsen, S. Investigating Workplace Bullying in India: Psychometric Properties, Validity, and Cutoff Scores of Negative Acts Questionnaire–Revised. SAGE Open 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, E.G.; Einarsen, S. Bullying in Danish Work-Life: Prevalence and Health Correlates. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullyonline. The Difference between Bullying and Harassment. Available online: https://www.bullyonline.org/index.php/bullying/3-the-difference-between-bullying-and-harassment (accessed on 7 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.; Notelaers, G.; Einarsen, S. Measuring Exposure to Workplace Bullying. Bullying Harass. Work. 2010, 133–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C. Bullying and Emotional Abuse in the Workplace: International Perspectives in Research and Practice; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Salin, D.; Cowan, R.; Adewumi, O.; Apospori, E.; Bochantin, J.; D’Cruz, P.; Djurkovic, N.; Durniat, K.; Escartín, J.; Guo, J.; et al. Workplace Bullying across the Globe: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Personal. Rev. 2019, 48, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S. Harassment and Bullying at Work: A Review of the Scandinavian Approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2000, 5, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, E.P. Workplace Bullying and Harassment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Agarwal, U. Workplace Bullying: A Review and Future Research Directions. South Asian J. Manag. 2016, 23, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Survey, U.S.W.B.; Namie, G. 2017 Workplace Bullying Institute Stopping the Bullying. 2017. Available online: https://anannkefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2017-WBI-US-Survey.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Zapf, D.; Gross, C. Conflict Escalation and Coping with Workplace Bullying: A Replication and Extension. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangar, R.U. Workplace Bullying; Boundary for Employees and Organizational Workplace Bullying; Boundary for Employees and Organizational Development; Dr. Rashad Yazdanifard American Degree Progr; Rupini Uthaya Shangar American Degree Program Upper Iowa University: Hong Kong, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, W.; LaVan, H. Workplace Bullying: A Review of Litigated Cases. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2010, 22, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baixauli, E.; Beleña, Á.; Díaz, A. Evaluation of the Effects of a Bullying at Work Intervention for Middle Managers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoel, H. Workplace Bullying in United Kingdom. Work. Bullying Harass. 2013, 61. Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/english/reports/documents/jilpt-reports/no.12.pdf#page=67 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Leymann, H. The Content and Development of Mobbing at Work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Thomas, H.; Gardner, D.; O’Driscoll, M.; Catley, B.; Bentley, T.; Trenberth, L. Neutralizing Workplace Bullying: The Buffering Effects of Contextual Factors. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Blanshard, C.; Child, S. The new zealand medical journal Workplace Bullying of Junior Doctors: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Survey. J. N. Zeal. Med. Assoc. NZMJ 2008, 121, 8716. [Google Scholar]

- Askew, D.A.; Schluter, P.J.; Dick, M.L.; Ŕgo, P.M.; Turner, C.; Wilkinson, D. Bullying in the Australian Medical Workforce: Cross-Sectional Data from an Australian e-Cohort Study. Aust. Health Rev. 2012, 36, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairy, K.; Thirumalaikolundusubramanian, P.; Sivagnanam, G.; Saraswathi, S.; Sachidananda, A.; Shalini, A. Bullying among Trainee Doctors in Southern India: A Questionnaire Study. J. Postgrad. Med. 2007, 53, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, V.; Hoel, H.; Cooper, C.L. Preventing Violence and Harassment in the Workplace; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Dublin, Ireland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Field, E.M. Strategies for Surviving Bullying at Work; Australian Academic Press: Queensland, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson’s, C. Bullying and Harassment. Occup. Health 2014, 66, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Bradfield, M. Perceived Victimization in the Workplace: The Role of Situational Factors and Victim Characteristics. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Grover, S.L.; Bradfield, M.; Allen, D.G. The Effects of Negative Affectivity, Hierarchical Status, and Self-Determination on Workplace Victimization. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, S.M.; MacIntosh, J.A. Gender and Workplace Bullying. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolfe, G.; Cirillo, M.; Iavarone, A.; Negro, A.; Garofalo, E.; Cotena, A.; Lazazzara, M.; Zontini, G.; Cirillo, S. Bullying at Workplace and Brain-Imaging Correlates. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Moore, M.; Crowley, N. The Clinical Effects of Workplace Bullying: A Critical Look at Personality Using SEM. Int. J. Work. Health Manag. 2011, 4, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmes, L. Bullying and Behavioural Conflict at Work: The Duality of Individual Rights; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Trépanier, S.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S. Workplace Bullying and Psychological Health at Work: The Mediating Role of Satisfaction of Needs for Autonomy, Competence and Relatedness. Work Stress Int. J. Work Health Organ. 2013, 27, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, E.Z.; Isahak, M.; Rampal, S.; Rosnah, I.; Zakaria, M.I. Individual Antecedents of Workplace Victimisation: The Role of Negative Affect, Personality and Self-Esteem in Junior Doctors’ Exposure to Bullying at Work. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pörhölä, M.; Karhunen, S.; Rainivaara, S. Bullying at School and in the Workplace: A Challenge for Communication Research. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2006, 30, 249–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Human Rights Commission. Good Practice, Good Business. Available online: https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/info_for_employers/pdf/7_workplace_bullying.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Daniel, T.A. Stop Bullying at Work:Strategies and Tools for HR and Legal Professionals; Society for Human Resource Management: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lutgen-Sandvik, P.; Tracy, S.J. Answering Five Key Questions about Workplace Bullying: How Communication Scholarship Provides Thought Leadership for Transforming Abuse at Work. Manag. Commun. Q. 2012, 26, 3–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, L.P. Bruising the Bottom Line: Cost of Workplace Bullying and the Compromised Access for Underrepresented Community College Employees. Divers. High. Educ. 2016, 18, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.; Bashir, S.; Earnshaw, V.A. Bullying, Internalized Hepatitis (Hepatitis C Virus) Stigma, and Self-Esteem: Does Spirituality Curtail the Relationship in the Workplace. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 1860–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluver, L.; Orkin, M. Cumulative Risk and AIDS-Orphanhood: Interactions of Stigma, Bullying and Poverty on Child Mental Health in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, M.; Barker, M.; Rayner, C. Applying Strategies for Dealing with Workplace Bullying. Int. J. Manpow. 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illing, J.; Thompson, N.; Paul, C.; Rothwell, C.; Kehoe, A.; Carter, M. Workplace Bullying: Measurements and Metrics to Use in the NHS Final Report for NHS Employers; Newcastle University: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Matthiesen, S.B.; Einarsen, S. Perpetrators and Targets of Bullying at Work: Role Stress and Individual Differences. Violence Vict. 2007, 22, 735–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Notelaers, G. Measuring Exposure to Bullying and Harassment at Work: Validity, Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work Stress 2009, 23, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Skogstad, A.; Matthiesen, S.B.; Glasø, L.; Aasland, M.S.; Notelaers, G.; Einarsen, S. Prevalence of Workplace Bullying in Norway: Comparisons across Time and Estimation Methods. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2009, 18, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francioli, L.; Conway, P.M.; Hansen, Å.M.; Holten, A.L.; Grynderup, M.B.; Persson, R.; Mikkelsen, E.G.; Costa, G.; Høgh, A. Quality of Leadership and Workplace Bullying: The Mediating Role of Social Community at Work in a Two-Year Follow-Up Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogh, A.; Hansen, Å.M.; Mikkelsen, E.G.; Persson, R. Exposure to Negative Acts at Work, Psychological Stress Reactions and Physiological Stress Response. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 73, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabarani, S. Can We End School Violence, Once and for All? Available online: https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2017/11/14/can-we-end-school-violence-once-and-for-all.html (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Fitriyah, L.; Rokhmawan, T. “You’re Fat and Not Normal!” From Body Image to Decision of Suicide. Indones. J. Learn. Educ. Couns. 2019, 1, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutgers. Stigma, Fear, Bullying and Sexuality in Indonesia: An Untold Perspective. Available online: https://rutgers.international/news/news-archive/stigma-fear-bullying-and-sexuality-indonesia-untold-perspective (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Jatim.idntimes.com. Sakit Hati Karena Di-Bully Gendut, Tega Membunuh dan Bakar Teman Kerja. Available online: https://jatim.idntimes.com/news/jatim/mohamad-ulil/sakit-hati-karena-di-bully-gendut-tega-membunuh-dan-bakar-teman-kerja (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Survey, N.C. K10 and K6 Scales. Available online: https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/k6_scales.php (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Randy, J.L.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Skogstad, A. Bullying at Work: Epidemiological Findings in Public and Private Organizations. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.S.; Grimsrud, A.; Myer, L.; Williams, D.R.; Stein, D.J.; Seedat, S. The Psychometric Properties of the K10 and K6 Scales in Screening for Mood and Anxiety Disorders in the South African Stress and Health Study. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 20, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, G.; Slade, T. Interpreting Scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2001, 25, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. Review of the Satisfaction with Life. Psychol. Assess. 1993, 5, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charilaos, K.; Michael, G.; Chryssa, B.-T.; Panagiota, D.; George, C.P.; Christina, D. Validation of the Negative Acts Questionnaire (NAQ) in a Sample of Greek Teachers. Psychology 2015, 6, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dujo López, V.; González Trijueque, D.; Graña Gómez, J.L.; Andreu Rodríguez, J.M. A Psychometric Study of a Spanish Version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised: Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Arenas, A.; Leon-Perez, J.M. An Operative Measure of Workplace Bullying: The Negative Acts Questionnaire across Italian Companies. Ind. Health 2011, 49, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawanto, D.W. An Analysis Of National Culture And Leadership Practices In Indonesia. J. Divers. Manag. 2009, 4, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, M. Understanding Indonesian Business Culture. Marvin Hough Int. Res. Anal. 2020, 1–17. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjRjPeH-vDvAhWFe30KHZ9qCr4QFjAAegQIAxAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fmiraservices.ca%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F05%2FMIRA-May-4-20-Understanding-Indonesian-Business-Culture.pdf&usg=AOvVaw09QAxIwLwqQsdjAfZg78tg (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Ngutor, D.; Corresponding, I. Workplace Bullying, Job Satisfaction and Job Performance among Employees in a Federal Hospital in Nigeria. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, P.; Leach, L.S.; Kiely, K.M. The Relationship Between Work Depression and Workplace Bullying Summary Report; Safe Work Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2013. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1702/wellbeing-depression-bullying-summary-report.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Bonde, J.P.; Gullander, M.; Hansen, Å.M.; Grynderup, M.; Persson, R.; Hogh, A.; Willert, M.V.; Kaerlev, L.; Rugulies, R.; Kolstad, H.A. Health Correlates of Workplace Bullying: A 3-Wave Prospective Follow-up Study. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2016, 42, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.A.; Björkqvist, K. Workplace Bullying and Occupational Stress among University Teachers: Mediating and Moderating Factors. Eur. J. Psychol. 2019, 15, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Virtanen, M.; Vartia, M.; Elovainio, M.; Vahtera, J.; Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. Workplace Bullying and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Depression. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 60, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, P.; Ocaktan, M.E.; Çelen, Ü.; Örsal, Ö. The Effect of Workplace Bullying Perception on Psychological Symptoms: A Structural Equation Approach. Saf. Health Work 2018, 9, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.C.; Advisor, F.; Schaffer, B. Workplace Bullying and Job Satisfaction: The Moderating Effect of Perceived Organizational Support University of North Carolina at Asheville. Proc. Natl. Conf. Undergrad. Res. 2014, 95–104. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.925.2807&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Nauman, S.; Malik, S.Z.; Jalil, F. How Workplace Bullying Jeopardizes Employees’ Life Satisfaction: The Roles of Job Anxiety and Insomnia. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, J.; Malone, M.; Varma, A.; Markel, C.; Biondic, D.; Tannock, R.; Humphries, T. Children’s Perceptions of Their ADHD Symptoms: Positive Illusions, Attributions, and Stigma. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2012, 27, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliance, A.-B. Bullying and Mental Health: Guidance for Teachers and Other Professionals SEN and Disability: Developing Effective Anti-Bullying Practice. 2015, pp. 1–27. Available online: https://www.anti-bullyingalliance.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/attachment/Mental-health-and-bullying-module-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Pradhan, A.; Joshi, J. Impact of Workplace Bullying on Employee Performance. Int. Res. J. Manag. Sci. 2019, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mete, E.S.; Sökmen, A. The Influence of Workplace Bullying on Employee’s Job Performance, Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention in a Newly Established Private Hospital. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2016, 5, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Panayiotou, E.A. Workplace Harassment and Depression in Mental Health Nurses: A National Survey from Cyprus. Community Med. Public Heal. Care 2019, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariadou, T.; Zannetos, S.; Chira, S.E.; Gregoriou, S.; Pavlakis, A. Prevalence and Forms of Workplace Bullying Among Health-Care Professionals in Cyprus: Greek Version of “Leymann Inventory of Psychological Terror” Instrument. Saf. Health Work 2018, 9, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, R.A.; Sansone, L.A. Workplace Bullying: A Tale of Adverse Consequences. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 12, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niedhammer, I.; David, S.; Degioanni, S. Association between Workplace Bullying and Depressive Symptoms in the French Working Population. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006, 61, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 2370 (75.5) |

| Female | 770 (24.5) |

| Age | |

| <25 years old | 390 (12.4) |

| 25–29 years old | 784(25) |

| 30–34 years old | 607 (19.3) |

| 35–40 years old | 558 (17.8) |

| >40 years old | 801 (25.5) |

| Educational Background | |

| Elementary School | 77 (2.5) |

| Junior High School | 141 (4.5) |

| Senior High School | 1042 (33.2) |

| Diploma (D3) | 365 (11.6) |

| Undergraduate (D4/S1) | 1327 (42.3) |

| Master Program (S2) | 185 (5.9) |

| Doctoral Program (S3) | 3 (0.1) |

| Types of Industry | |

| Oil and Gas | 727 (23.2) |

| Manufacturing | 228 (7.3) |

| Construction | 1011 (32.2) |

| Education | 351 (11.2) |

| Health services | 327 (10.4) |

| Call Centre | 201 (6.4) |

| Power plant | 220 (7) |

| Others | 75 (2.2) |

| Level of Position | |

| Operator/Admin | 968 (30.8) |

| Staff | 922 (29.4) |

| Supervisor | 327 (10.4) |

| Assistant Manager | 97 (3.1) |

| Manager | 167 (5.3) |

| Others | 659 (21) |

| Employment Status | |

| Permanent employee | 1267 (40.3) |

| Contract employee | 1219 (38.8) |

| Outsourcing/third party employee | 437 (13.9) |

| Daily | 220 (7) |

| Duration of working | |

| <3 years | 1398 (44.6) |

| 4–6 years | 487 (15.5) |

| 7–10 years | 518 (16.4) |

| >10 years | 714 (22.7) |

| Minimum Wage | |

| Under Minimum Regional Wage (UMR) | 303 (9.6) |

| Similar Minimum Regional Wage (SMR) | 987 (31.4) |

| Higher than Minimum Regional Wage (HMR) | 1850 (58.9) |

| History of illness (experience of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart problems, stroke, osteoporosis, hypertension, etc.) | |

| Yes | 212 (6.8) |

| No | 2696 (85.9) |

| Unknown | 225 (7.2) |

| Absenteeism (Due to illness) | |

| 0 day | 1785 (56.8) |

| 1–5 days | 1120 (35.7) |

| 6–10 days | 146 (4.6) |

| >10 days | 89 (2.8) |

| Absenteeism (Due to non-illness) | |

| 0 day | 1460 (46.5) |

| 1–5 days | 1213 (38.6) |

| 6–10 days | 275 (8.8) |

| >10 days | 192 (6.1) |

| Instrument | N | N Items | Cronbach’s (α) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAQ-R Total | 3140 | 22 | 0.897 |

| Factor 1 (person-related bullying) | 3140 | 11 | 0.860 |

| Factor 2 (work-related bullying) | 3140 | 7 | 0.777 |

| Factor 3 (intimidation towards a person) | 3140 | 4 | 0.721 |

| Psychosocial Distress | 3140 | 10 | 0.881 |

| Satisfaction with life | 3140 | 5 | 0.841 |

| Factor | Item | Item Wording * | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 (person-related bullying) | 2 | Being humiliated or ridiculed in connection with your work (p) (pw’) (p”) | 0.605 |

| 5 | Spreading of gossip and rumors about you (p) (pw’) (p”) | 0.594 | |

| 6 | Being ignored or excluded (being ‘sent to Coventry’) (p) (pw’) (p”) | 0.634 | |

| 7 | Having insulting or offensive remarks made about your person (i.e., habits and background), your attitudes, or your private life (p) (pw’) (p”) | 0.716 | |

| 9 | Intimidating behavior such as finger-pointing, invasion of personal space, shoving, or blocking/barring the way (i) (pw’) (p”) | 0.530 | |

| 10 | Hints or signals from others that you should quit your job (p) (pi’) (p”) | 0.636 | |

| 12 | Being ignored or facing a hostile reaction when you approach (p) (pw’) (p”) | 0.583 | |

| 15 | Practical jokes carried out by people you do not get on with (p) (pi’) (p”) | 0.661 | |

| 17 | Having allegations made against you (p) (pw’) (p”) | 0.517 | |

| 20 | Being the subject of excessive teasing and sarcasm (p) (pw’) | 0.712 | |

| 22 | Threats of violence or physical abuse or actual abuse (i) (pi’) | 0.584 | |

| Factor 2 (work-related bullying) | 1 | Someone withholding information which affects your performance (w) (pw’) (w”) | 0.515 |

| 3 | Being ordered to do work below your level of competence (w) (od’) (w”) | 0.595 | |

| 4 | Having key areas of responsibility removed or replaced with more trivial or unpleasant tasks (p) (od’) (w”) | 0.603 | |

| 14 | Having your opinions and views ignored (w) (pw’) (p”) | 0.595 | |

| 16 | Being given tasks with unreasonable or impossible targets or deadlines (w) (pw’) (w”) | 0.657 | |

| 19 | Pressure not to claim something which by right you are entitled to (e.g., sick leave, holiday entitlement, travel expenses) (w) (pw’) | 0.474 | |

| 21 | Being exposed to an unmanageable workload (w) (pw’) (w”) | 0.639 | |

| Factor 3 (intimidation towards a person) | 8 | Being shouted at or being the target of spontaneous anger (or rage) (i) (pw’) (p”) | 0.633 |

| 11 | Repeated reminders of your errors or mistakes (p) (pw’) | 0.589 | |

| 13 | Persistent criticism of your work and effort (p) (pw’) (p”) | 0.663 | |

| 18 | Excessive monitoring of your work (w) (pw’) (w”) | 0.636 |

| No | Item | Mean (SD) | 5 Psychosocial Distress | 6 Satisfaction with Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NAQ-R Total | 27.50 (6.43) | 0.627 | −0.242 |

| 2 | Person-related bullying | 12.72 (2.90) | 0.515 | −0.227 |

| 3 | Work-related bullying | 9.37 (2.69) | 0.566 | −0.163 |

| 4 | Intimidation towards a person | 5.41 (1.90) | 0.505 | −0.246 |

| 5 | Psychosocial Distress | 16.54 (5.77) | 1 | |

| 6 | Satisfaction with life | 22.97 (6.15) | −0.307 | 1 |

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Bullied at work | |

| No | 2801 (89.2) |

| Yes, but rarely | 255 (8.1) |

| Yes, now and then | 67 (2.1) |

| Yes, several times in a week | 10 (0.3) |

| Yes, almost daily | 7 (0.2) |

| Perpetrators | |

| Immediate superior | 76 (2.4) |

| Other superiors/managers in the organization | 67 (2.1) |

| Colleagues | 266 (8.5) |

| Subordinates | 27 (0.9) |

| Customers/patients/students, etc. | 26 (0.8) |

| Others | 16 (05) |

| The number and gender of perpetrators Male perpetrators | |

| None | 2862 (91.1) |

| 1–2 persons | 197 (6.3) |

| 3–4 persons | 50 (1.6) |

| 5–6 persons | 21 (0.7) |

| >6 persons | 10 (0.3) |

| Female perpetrators | |

| None | 2983 (95) |

| 1–2 persons | 117 (3.7) |

| 3–4 persons | 22 (0.7) |

| 5–6 persons | 10 (0.3) |

| >6 persons | 2 (0.0) |

| Over the Last Six Months, How Often Have You Been Subjected to the Following Negative Acts at Work | Never (%) | Now and then (%) | Monthly (%) | Weekly (%) | Daily (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 (63.3) | 1079 (34.4) | 28 (0.9) | 25 (0.8) | 19 (0.6) |

| 2451 (78.1) | 647 (20.6) | 31 (1) | 8 (0.3) | 3 (0.1) |

| 1987 (63) | 1306 (33) | 52 (1.7) | 24 (0.8) | 50 (1.6) |

| 2525 (80.4) | 555 (17.7) | 24 (0.8) | 21 (0.7) | 15 (0.5) |

| 2107 (67.1) | 968 (30.8) | 27 (0.9) | 17 (0.5) | 21 (0.7) |

| 2710 (86.3) | 408 (13) | 10 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | 7 (0.2) |

| 2686 (85.5) | 432 (13.8) | 10 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) |

| 2464 (78.5) | 620 (19.7) | 31 (1) | 22 (0.7) | 3 (0.1) |

| 2948 (93.9) | 175 (5.6) | 9 (0.3) | 4 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) |

| 2834 (90.3) | 281 (8.9) | 12 (0.4) | 6 (0.2) | 7 (0.2) |

| 1927 (61.4) | 1028 (32.7) | 83 (2.6) | 53 (1.7) | 49 (1.6) |

| 2602 (82.9) | 521 (16.6) | 9 (0.3) | 4 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) |

| 2034 (64.8) | 985 (31.4) | 70 (2.2) | 34 (1.1) | 17 (0.5) |

| 1748 (55.7) | 1336 (42.5) | 30 (1) | 9 (0.3) | 17 (0.5) |

| 2560 (81.5) | 551 (17.5) | 15 (0.5) | 5 (0.2) | 9 (0.3) |

| 2030 (64.6) | 950 (30.3) | 91 (2.9) | 46 (1.5) | 23 (0.7) |

| 2844 (90.6) | 280 (8.9) | 10 (0.3) | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) |

| 2515 (80.1) | 510 (16.2) | 58 (1.8) | 26 (0.8) | 31 (1) |

| 2797 (89.1) | 315 (10) | 21 (0.7) | 3 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) |

| 2885 (91.9) | 243 (7.7) | 8 (0.3) | 1 (0.0) | 3 (0.1) |

| 2454 (78.2) | 630 (20.1) | 37 (1.2) | 9 (0.3) | 10 (0.3) |

| 2977 (94.8) | 153 (4.9) | 7 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erwandi, D.; Kadir, A.; Lestari, F. Identification of Workplace Bullying: Reliability and Validity of Indonesian Version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083985

Erwandi D, Kadir A, Lestari F. Identification of Workplace Bullying: Reliability and Validity of Indonesian Version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083985

Chicago/Turabian StyleErwandi, Dadan, Abdul Kadir, and Fatma Lestari. 2021. "Identification of Workplace Bullying: Reliability and Validity of Indonesian Version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083985

APA StyleErwandi, D., Kadir, A., & Lestari, F. (2021). Identification of Workplace Bullying: Reliability and Validity of Indonesian Version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083985