Examination of Symptoms of Depression among Cooperative Dairy Farmers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Survey Development

2.4. Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Operation Characteristics

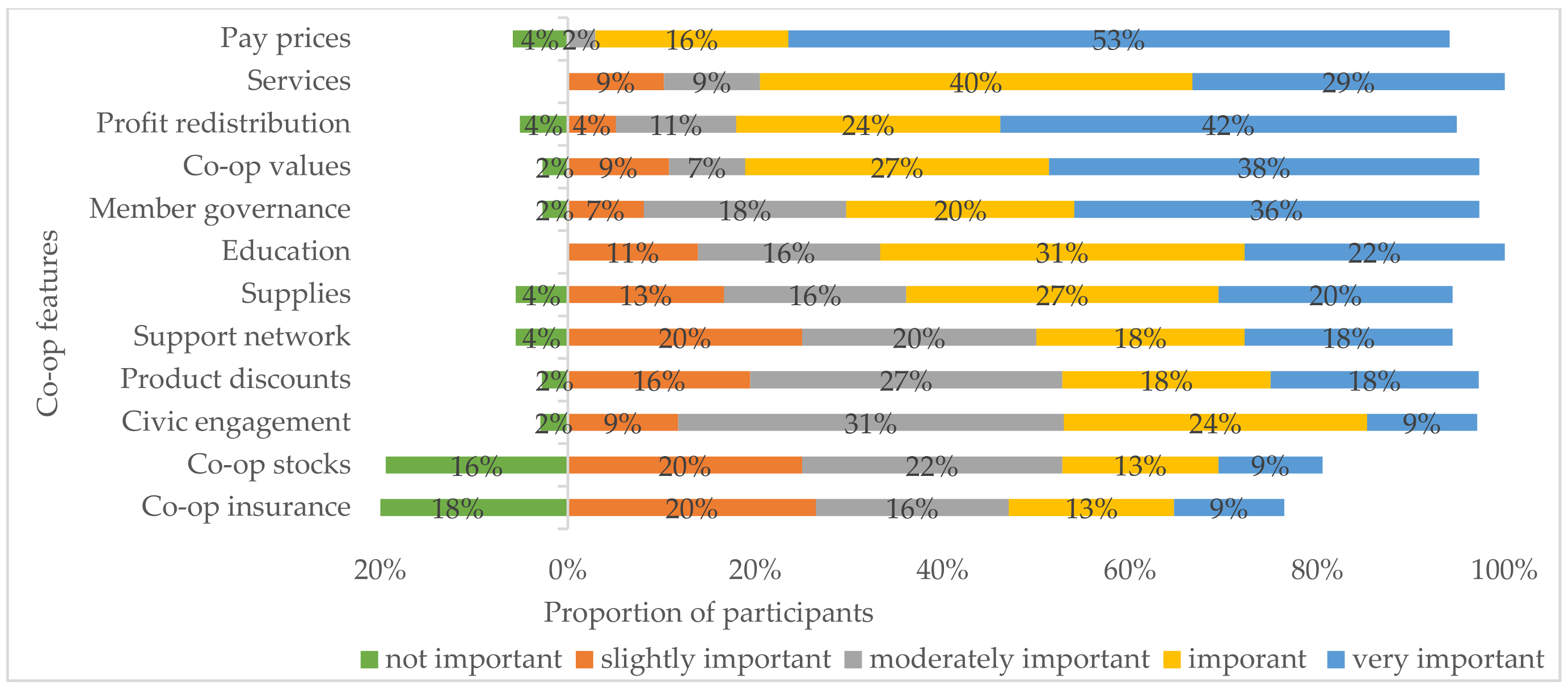

3.2. Co-op Attributes

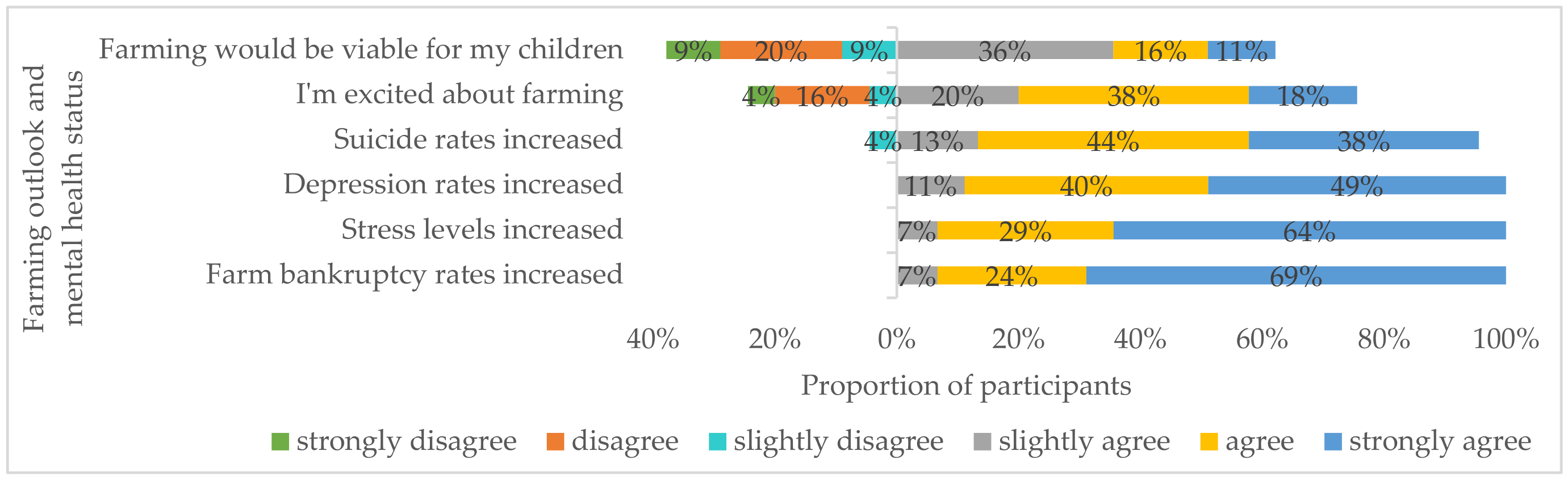

3.3. Mental Health Status among Farmers

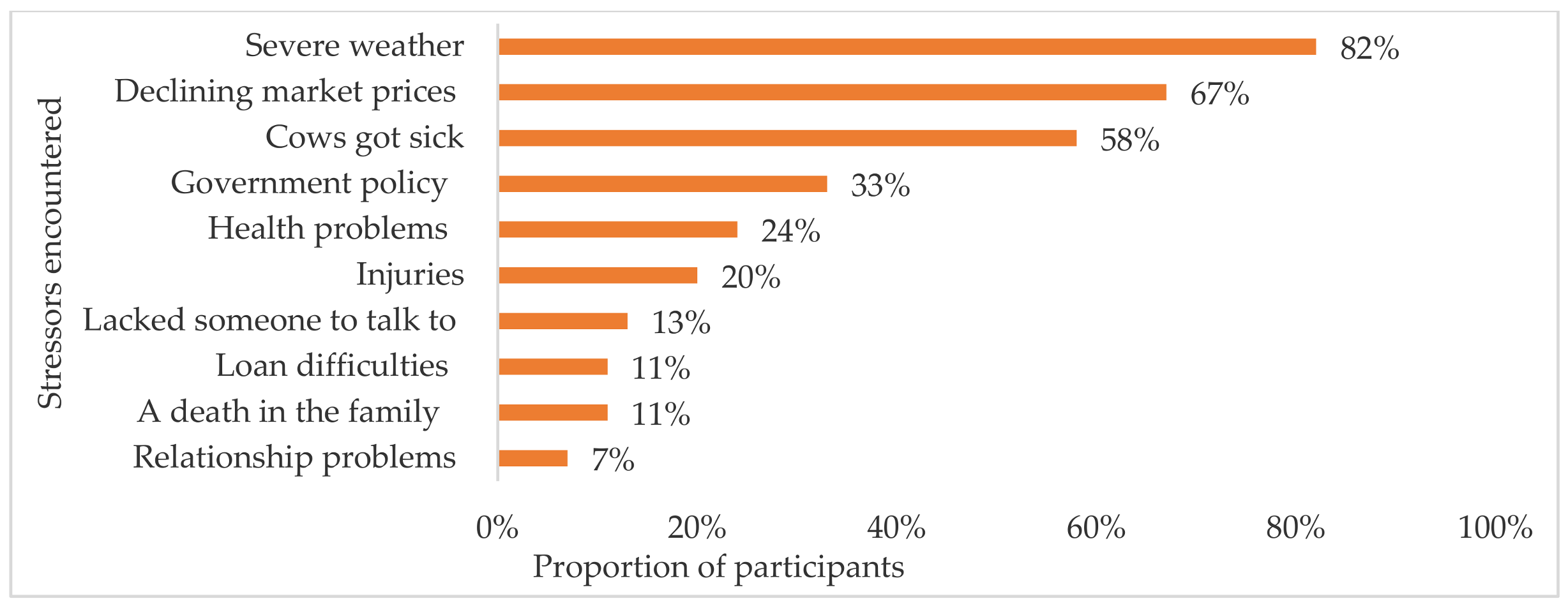

3.4. Stressors

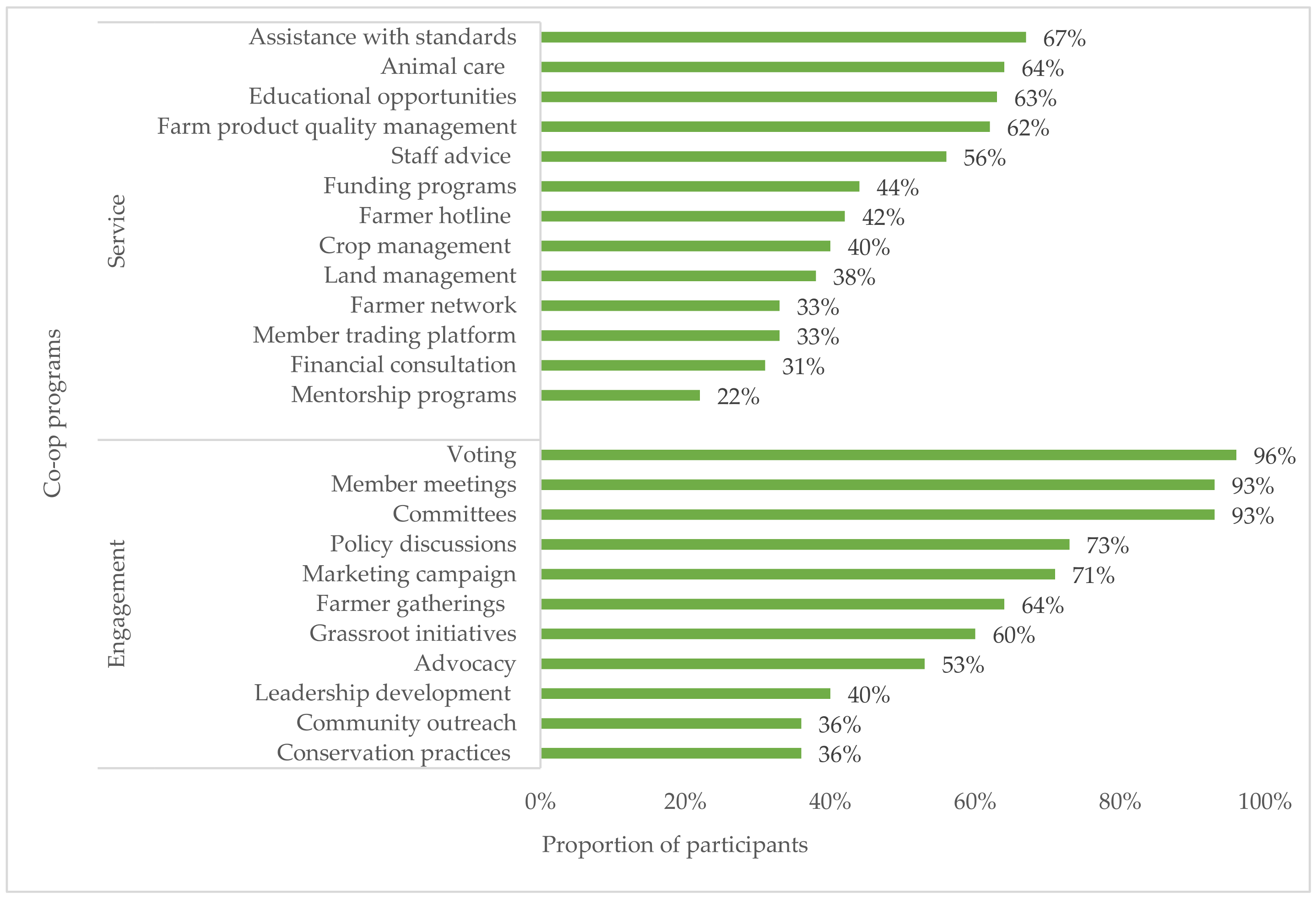

3.5. Co-op Services and the Symptoms of Depression Score

3.6. Co-op Engagement Activities and Symptoms of Depression Score

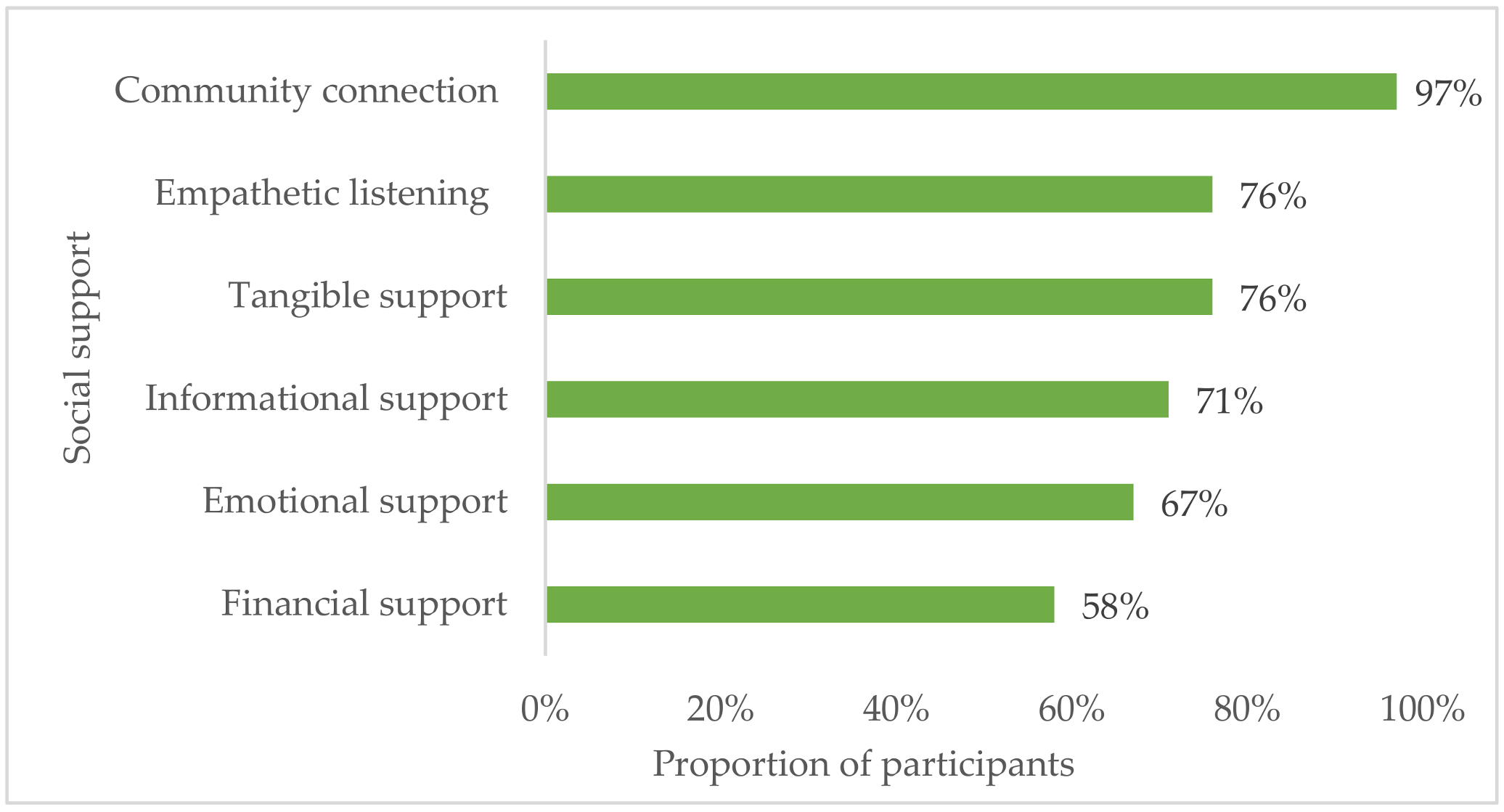

3.7. Social Support Availability and Symptoms of Depression Score

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Themes | Core Survey Items |

|---|---|

| Stress among Famers: Farm bankruptcy Stress Depression Suicide | Rank the following statements (on a 6-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree):

|

| Stressors: Occupational Financial Relationship Isolation Loneliness | During the last 12 months were you in any of the following situations? (check all that apply)

|

| Co-op Services: Advice Technical support Education/training/ mentorship Financial consultation Funding opportunities | Please indicate whether these services and resources offered by your co-ops during the last 12 months. (Services and resources include technical support, consultations and education offered by co-ops to assist members in farm practice and professional development.) Participants indicating “yes” offered were asked: Please enter the number of times you used the services and resources offered by your co-ops during the last 12 months AND rank your satisfaction. Participants entering a none zero number were asked: How satisfied are you with the _____ from your co-ops? (on a 6-point scale from 1 = strongly dissatisfied to 6 = strongly satisfied)

|

| Co-op Engagement: Meetings Decision-making Civic engagement Leadership Advocacy Social interactions Representation | Please indicate if these engagement activities were offered by any of the co-ops you were a member of during the last 12 months: (Engagement activities include activities and events offered or sponsored by co-ops that encourage members to participate in co-op affairs.) Participants indicating “yes” offered were asked: Please enter the number of times you participated in these engagement activities of your co-ops during the last 12 months AND rank your satisfaction. Participants entering a none zero number were asked: How satisfied are you with the _____ from your co-ops? (on a 6-point scale from 1 = strongly dissatisfied to 6 = strongly satisfied)

|

| Role of Co-ops in Farmers’ Mental Health: Services Engagement programs Support networks | The following statements may be protective factors for farmers’ mental health. Indicate the extent to which you agree and disagree to the following conditions (on a 6-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree):

|

References

- Reed, B.D.; Claunch, T.D. Risk for depressive symptoms and suicide among U.S. primary farmers and family members: A systematic literature review. Workplace Health Saf. 2020, 68, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belyea, M.J.; Lobao, L.M. Psychosocial consequences of agricultural transformation: The farm crisis and depression. Rural Sociol. 1990, 55, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolphi, M.J.; Berg, L.R.; Parsaik, A. Depression, anxiety and stress among young farmers and ranchers: A pilot study. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarth, R.D.; Stallones, L.; Zwerling, C.; Burmeister, L.F. The prevalence of depressive symptoms and risk factors among Iowa and Colorado farmers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2000, 37, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringgenberg, W.; Peek-Asa, C.; Donham, K.; Ramirez, M. Trends and characteristics of occupational suicide and homicide in farmers and agriculture workers, 1992–2010. J. Rural Health. 2018, 34, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.; Stone, D.; Marsh, S.; Schumacher, P.K.; Tiesman, H.M.; McIntosh, W.L.; Lokey, C.N.; Trudeau, A.T.; Bartholow, B.; Luo, F. Suicide rates by occupational group—17 States, 2012 and 2015. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Suicide. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Daghagh, S.Y.; Wheeler, A.S.; Zuo, A. Key risk factors affecting farmers’ mental health: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, J.R.; Crooks, A.C.; Frederick, D.A.; Kennedy, T.L.; Wadsworth, J.J. Agricultural Cooperatives in the 21st Century; USDA Rural Business-Cooperative Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cropp, B.; Graf, T. The History and Role of Dairy Cooperatives; UW Center for Cooperatives: Madison, WI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schneiberg, M.; King, M.; Smith, T. Social movements and organizational form: Cooperative alternatives to corporations in the American insurance, dairy, and grain industries. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 73, 635–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebrand, B.C. Dairy Cooperatives in the 21st Century: The First Decade; USDA Rural Business and Cooperative Programs: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth, J.; Coleman, C. Agricultural Cooperative Statistics 2017; USDA Rural Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, M.D.; Armstrong, P.S. The farm crisis: An analysis of social psychological distress among North Carolina farm operators. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1989, 17, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stain, H.J.; Kelly, B.; Lewin, T.J.; Higginbotham, N.; Beard, J.R.; Hourihan, F. Social networks and mental health among a farming population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornestad, A.; Brown, L.; Weidauer, L. The relationship between social support and depressive symptoms in Midwestern farmers. J. Rural Ment. Health 2019, 43, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Rohlman, D.; Janssen, B.; Casteel, C.; Nonnenmann, M. Agricultural cooperatives in mental health: Farmers’ perspectives on potential influence. J. Rural Stud. 2021. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, E.H.; Curry, L.A.; Spatz, E.S.; Herrin, J.; Cherlin, E.J.; Curtis, J.P.; Thompson, J.W.; Ting, H.H.; Wang, Y.; Krumholz, H.M. Hospital strategies for reducing risk-standardized mortality rates in acute myocardial infarction. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 156, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.C.; Polen, R.M.; Janoff, L.S.; Castleton, D.K.; Wisdom, J.P.; Vuckovic, N.; Perrin, N.A.; Paulson, R.I.; Oken, S.L. Understanding how clinician-patient relationships and relational continuity of care affect recovery from serious mental illness: STARS Study results. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2008, 32, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, I.G.; Levine, M.H.; Basham, B.R.; Sarason, R.B. Assessing social support: The Social Support Questionnaire. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, I.G.; Sarason, B.R.; Shearin, E.N.; Pierce, G.R. A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoretical implications. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1987, 4, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, V.M. Family response to the farm crisis: A study in coping. Soc. Work 1990, 35, 425–431. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, S.T.; Johnson, D.R.; Beeson, P.G.; Craft, B.J. The farm crisis and mental-health: A longitudinal-study of the 1980s. Rural Sociol. 1994, 59, 598–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohout, F.J.; Berkman, L.F.; Evans, D.A.; Cornoni-Huntley, J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J. Aging Health 1993, 5, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; O’Brien, N.; Forrest, J.I.; Salters, K.A.; Patterson, T.L.; Montaner, J.S.; Hogg, R.S.; Lima, V.D. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andresen, E.M.; Malmgren, J.A.; Carter, W.B.; Patrick, D.L. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1994, 10, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Carlo, G.; Grant, K.; Trinidad, N.; Correa, A. Stress, depression, and occupational injury among migrant farmworkers in Nebraska. Safety 2016, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Alterman, T.; Muntaner, C.; Shen, R.; Li, J.; Gabbard, S.; Nakamoto, J.; Carroll, D.J. Mental health research with Latino farmworkers: A systematic evaluation of the short CES-D. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2010, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. 2017 Census of Agriculture; USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman, C.H.; Rapp, G.; Ingalsbe, G.; Duffey, P.; Wadsworth, J. Co-Op Essentials: What They Are and the Role of Members, Directors, Managers, and Employees; USDA Rural Development Cooperative Programs: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, B.J. Decision-Making in Cooperatives with Diverse Member Interests; USDA Rural Business-Cooperative Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, F.; Jackson, H.; Komiti, A.; Murray, G.; Fraser, C.; Grieve, A.; Gomez, R. Help-seeking by rural residents for mental health problems: The importance of agrarian values. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassley, C.; Tester, J.; Brindisi, A.; Craig, A.; Katko, J. Seeding Rural Resilience Act; United States Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, T.; Ernst, J.; Moran, J.; Heitkamp, H.; Gardner, C.; Bennet, M.F.; Hoeven, J.; Smith, T.; Grassley, C.; McCaskill, C.; et al. FARMERS FIRST Act; United States Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, M. Assessing Occupational Health among Transitional Agricultural Workforces: A mixed Methods Study among US Beginning Farmers and South Indian Tea Harvesting Workers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA, May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Bitton, A.; Best, C.; MacTavish, J.; Fleming, S.; Hoy, S. Stress, anxiety, depression, and resilience in Canadian farmers. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, B.; Nonnenmann, W.M. Public health science in agriculture: Farmers’ perspectives on respiratory protection research. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 55, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.C.; Bondy, M.C. Madeleine, Meeting farmers where they are—Rural clinicians’ views on farmers’ mental health. J. Agromed. 2020, 25, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perceval, M.; Ross, V.; Kõlves, K.; Reddy, P.; De Leo, D. Social factors and Australian farmer suicide: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Tremblay, G.; Oliffe, J.L.; Jbilou, J.; Robertson, S. Male farmers with mental health disorders: A scoping review. Aust. J. Rural Health 2013, 21, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, S.K.; Jenkin, G.; Collings, S. Men’s perspectives of common mental health problems: A metasynthesis of qualitative research. Int. J. Men’s Health. 2016, 15, 80–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torvik, F.A.; Rognmo, K.; Tambs, K. Alcohol use and mental distress as predictors of non-response in a general population health survey: The HUNT study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Llorca, J. Bias. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2004, 58, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, M.K.; Pratt, C.; Galea, S.; McLaughlin, A.K.; Koenen, C.K.; Shear, K.M. The burden of loss: Unexpected death of a loved one and psychiatric disorders across the life course in a national study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014, 171, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.A.; Schwab, C.V.; Jiang, Q. Quantifying stressors among Iowa farmers. J. Agric. Saf. Health. 2008, 14, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, S.; Challis, C. Resilience among men farmers: The protective roles of social support and sense of belonging in the depression-suicidal ideation relation. Death Stud. 2009, 33, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariepy, G.; Honkaniemi, H.; Quesnel-Vallee, A. Social support and protection from depression: Systematic review of current findings in western countries. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 209, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, Z.I.; Koyanagi, A.; Tyrovolas, S.; Mason, C.; Haro, J.M. The association between social relationships and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukull, W.A.; Ganguli, M. Generalizability: The trees, the forest, and the low-hanging fruit. Neurology 2012, 78, 1886–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Themes | Core Survey Items |

|---|---|

| Co-op Resources: Attributes Services Engagement activities | Thinking about your experience with all the co-ops you are a member of, rank how important the following co-op attributes are to you (on a 5-point scale from 1 = not important to 5 = very important):

|

| Demographics and Farming Characteristics | Median [(Interquartile Range (IQR)] | Percent (n) | Symptoms of Depression Median Score (IQR) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54 (39–61) | 0.1694 | ||

| ≤54 years | 51% (23) | 9 (4–11) | ||

| >54 years | 49% (22) | 5 (3–12) | ||

| Sex | 0.2031 | |||

| Male | 60% (27) | 7 (4–11) | ||

| Female | 38% (17) | 8 (4–11) | ||

| Other | 2% (1) | 22 (22–22) | ||

| Marital Status | 0.1613 | |||

| Married | 93% (42) | 7 (4–11) | ||

| Unmarried | 7% (3) | 10.5 (9–12) | ||

| Living Situation | 0.0139 | |||

| Alone | 9% (4) | 14.5 (10.5–23.5) | ||

| Not alone | 91% (41) | 7 (4–10) | ||

| Owner-Operator | * | |||

| Yes | 98% (44) | 7.5 (4.0–11.5) | ||

| No | 2% (1) | 10 (10–10) | ||

| Primary Source of Household Income ** | 0.1526 | |||

| Farming | 76% (34) | 6.5 (4–11) | ||

| Off-farm employment | 22% (10) | 8.5 (7–14) | ||

| Farm Enterprise | 0.4046 | |||

| Dairy | 67% (30) | 7.5 (4–11) | ||

| Non-dairy | 33% (15) | 8 (4–12) | ||

| Dairy Herd Size (head) | 70 (45–100) | 0.1292 | ||

| ≤70 | 71% (32) | 7 (3.5–11.0) | ||

| >70 | 29% (13) | 8 (5–16) | ||

| Field Crop Size (acres) | 315 (120–500) | 0.0929 | ||

| ≤315 | 80% (36) | 7 (4.0–10.5) | ||

| >315 | 20% (9) | 9 (8–16) | ||

| Years of Farming | 30 (10–38) | 0.4908 | ||

| ≤30 | 58% (26) | 8.5 (4–11) | ||

| >30 | 42% (19) | 6 (4–17) | ||

| Co-op Membership | 0.7908 | |||

| Co-op A | 31% (14) | 7 (4–10) | ||

| Co-op B | 36% (16) | 7.5 (4.0–10.5) | ||

| Co-op C | 13% (6) | 8 (3–11) | ||

| Dual memberships (A and C, B and C) | 18% (8) | 7.5 (3.5–12) | ||

| Other | 2% (1) | 17 (17–17) |

| Stressors Occurring during the Last 12 Months | Symptoms of Depression Median Score (Interquartile Range) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Severe weather negatively affected crops or livestock | 0.2758 | |

| Yes | 7 (4–10) | |

| No | 9.5 (4–16.5) | |

| Declining market prices negatively affected farm income | 0.037 | |

| Yes | 9 (4–16) | |

| No | 5 (3–9) | |

| Sick cows | 0.0043 | |

| Yes | 9.5 (5–14) | |

| No | 4 (3–8) | |

| Government policy negatively affected operation | 0.1671 | |

| Yes | 9 (5–11) | |

| No | 7 (3–12) | |

| Health problems (e.g., chronic conditions, backpain) | 0.0545 | |

| Yes | 10 (6–18) | |

| No | 7 (4–11) | |

| Injuries | 0.0028 | |

| Yes | 10 (10–17) | |

| No | 5.5 (3.5–10.5) | |

| Lacked someone to talk to | 0.0022 | |

| Yes | 16.5 (10–21) | |

| No | 7 (4–10) | |

| A death in the family | 0.0059 | |

| Yes | 2.5 (1.5–4) | |

| No | 8 (4–12) | |

| Difficulties getting operating loans | 0.0062 | |

| Yes | 20 (13–26) | |

| No | 7 (4–10) | |

| Relationship problems (e.g., divorced or separated) | 0.0046 | |

| Yes | 18 (17–30) | |

| No | 7 (4–10) |

| Co-op Services | Symptoms of Depression Median Score (Interquartile Range) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Educational opportunities | 0.0426 | |

| Available | 7.5 (4–11) | |

| Unavailable | 9 (5–12) | |

| Mentorship programs | 0.041 | |

| Available | 7.5 (3–10) | |

| Unavailable | 8 (4–12) | |

| Staff advice | 0.0423 | |

| Available | 8 (4–11) | |

| Unavailable | 8 (4.0–11.5) | |

| Farmer network | 0.0692 | |

| Available | 5 (3–10) | |

| Unavailable | 9 (4–12) | |

| Assistance with standards * | 0.1101 | |

| Available | 8.5 (4–14) | |

| Unavailable | 5 (3–10) | |

| Crop management * | 0.1145 | |

| Available | 6.5 (4–11) | |

| Unavailable | 9 (4–12) | |

| Farm product quality management * | 0.1305 | |

| Available | 7.5 (4.0–14.5) | |

| Unavailable | 8 (5–10) | |

| Financial consultation ** | 0.1321 | |

| Available | 7.5 (4–12) | |

| Unavailable | 8 (4–11) | |

| Animal care * | 0.2203 | |

| Available | 8 (3–14) | |

| Unavailable | 7 (5–10) | |

| Land management * | 0.2647 | |

| Available | 7 (4–14) | |

| Unavailable | 8.5 (4.0–10.5) | |

| Funding programs ** | 0.3786 | |

| Available | 10 (4–17) | |

| Unavailable | 5.5 (3–10) | |

| Farmer hotline | 0.3084 | |

| Available | 10 (4–17) | |

| Unavailable | 5.5 (3–10) | |

| Member trading platform | 0.4904 | |

| Available | 8 (3–11) | |

| Unavailable | 7 (4–12) |

| Co-op Engagement Activities | Symptoms of Depression Median Score (Interquartile Range) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Policy discussions | 0.0325 | |

| Available | 9 (4–12) | |

| Unavailable | 5 (3.5–9.0) | |

| Member meetings | 0.0515 | |

| Available | 7.5 (4–11) | |

| Unavailable | 10 (5–12) | |

| Farmer gatherings | 0.0949 | |

| Available | 8 (4–11) | |

| Unavailable | 7 (3.5–11.5) | |

| Marketing campaign | 0.1271 | |

| Available | 7 (4.0–10.5) | |

| Unavailable | 9 (5–12) | |

| Committees | 0.1551 | |

| Available | 7.5 (4–11) | |

| Unavailable | 10 (5–12) | |

| Voting | 0.1207 | |

| Available | 8 (4–11) | |

| Unavailable | 8.5 (5–12) | |

| Conservation practices | 0.2433 | |

| Available | 7.5 (4.0–10.5) | |

| Unavailable | 8 (4–12) | |

| Leadership development | 0.2556 | |

| Available | 8.5 (4–11) | |

| Unavailable | 7 (4–12) | |

| Community outreach | 0.2082 | |

| Available | 7.5 (4–12) | |

| Unavailable | 8 (4–11) | |

| Grassroot initiatives | 0.3559 | |

| Available | 8 (4–11) | |

| Unavailable | 7.5 (4–12) | |

| Advocacy | 0.4103 | |

| Available | 5.5 (3.0–10.5) | |

| Unavailable | 8 (5–12) |

| Types of Social Support | Symptoms of Depression Median Score (Interquartile Range) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional (when struggling) | 0.0126 | |

| Available | 6 (4–9) | |

| Unavailable | 11 (6–17) | |

| Informational (questions about farm operation) | 0.0157 | |

| Available | 6 (3.5–10.0) | |

| Unavailable | 10 (8–17) | |

| Tangible (help with farm chores) | 0.0237 | |

| Available | 7 (4–10) | |

| Unavailable | 11 (6–18) | |

| Financial (concerns about farm finance) | 0.0545 | |

| Available | 7 (3–10) | |

| Unavailable | 9 (4–17) | |

| Empathetic listening (someone to listen to) | 0.1173 | |

| Available | 7 (4–11) | |

| Unavailable | 10 (4–16) | |

| Community connection (member of other groups or organizations) | 0.439 | |

| Available | 8 (4.0–11.5) | |

| Unavailable | 7 (7–7) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, Y.; Wang, K.; Janssen, B.; Casteel, C.; Nonnenmann, M.; Rohlman, D.S. Examination of Symptoms of Depression among Cooperative Dairy Farmers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073657

Liang Y, Wang K, Janssen B, Casteel C, Nonnenmann M, Rohlman DS. Examination of Symptoms of Depression among Cooperative Dairy Farmers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(7):3657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073657

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Yanni, Kai Wang, Brandi Janssen, Carri Casteel, Matthew Nonnenmann, and Diane S. Rohlman. 2021. "Examination of Symptoms of Depression among Cooperative Dairy Farmers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 7: 3657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073657

APA StyleLiang, Y., Wang, K., Janssen, B., Casteel, C., Nonnenmann, M., & Rohlman, D. S. (2021). Examination of Symptoms of Depression among Cooperative Dairy Farmers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073657