Association between Work-Related Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms among Child Welfare Workers in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

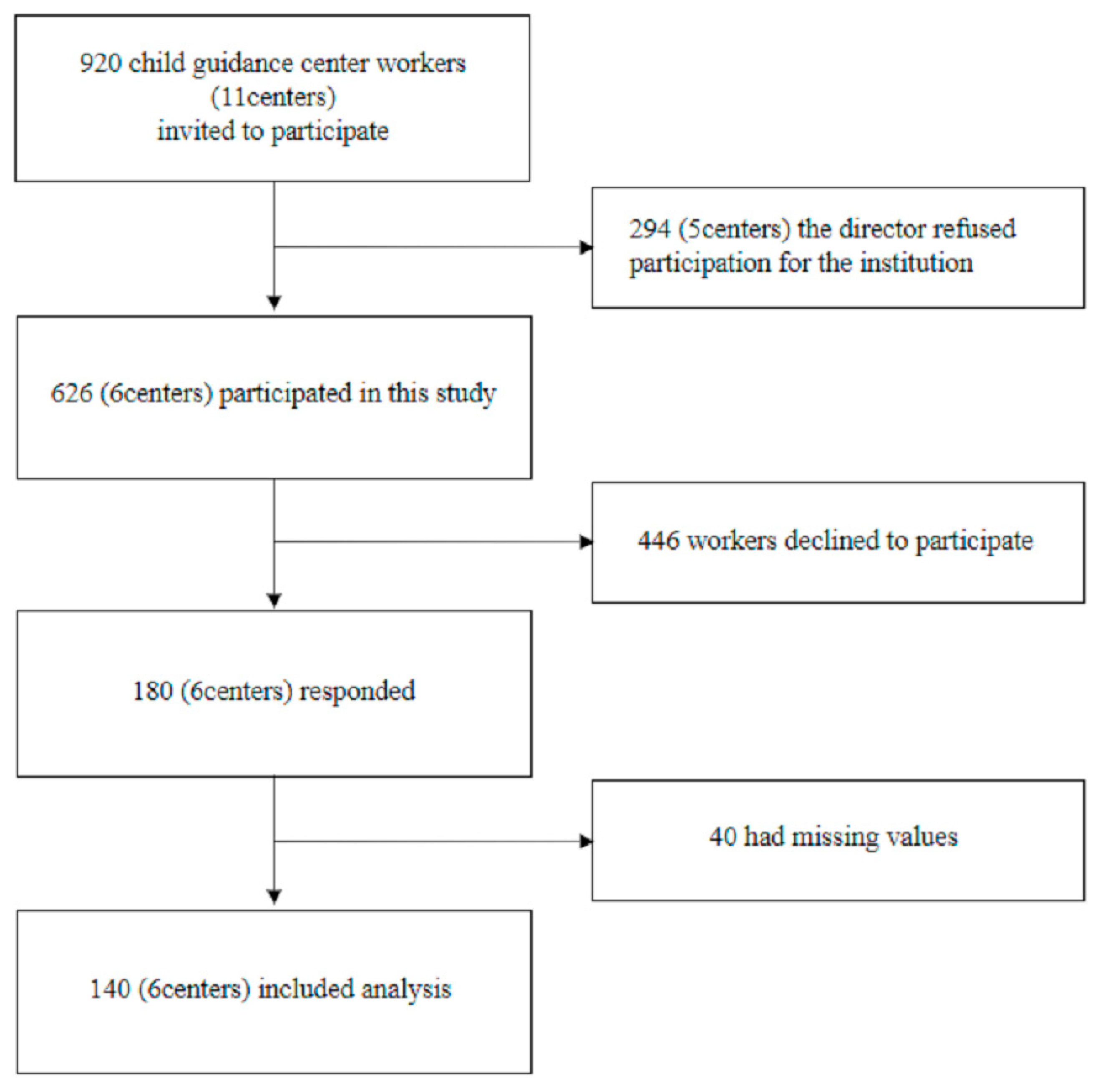

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Outcomes: The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)

2.3.2. Exposure: Work-Related Traumatic Events Checklist

2.3.3. Covariates

Brief Job Stress Questionnaire (BJSQ)

Tachikawa Resilience Scale (TRS)

2.3.4. Demographics and Characteristics

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tortella-Feliu, M.; Fullana, M.A.; Pérez-Vigil, A.; Torres, X.; Chamorro, J.; Littarelli, S.A.; Solanes, A.; Ramella-Cravaro, V.; Vilar, A.; González-Parra, J.A.; et al. Risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 107, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Brown, D.S.; Florence, C.S.; Mercy, J.A. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abus. Negl. 2012, 36, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, I.; Igarashi, A. The social costs of child abuse in Japan. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 46, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child Guidance Center in Tokyo. Operations Overview; Child Guidance Center in Tokyo: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Regehr, C.; Leblanc, V.R. PTSD, Acute Stress, Performance and Decision-Making in Emergency Service Workers. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2017, 45, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Breslau, N.; Chilcoat, H.D.; Kessler, R.C.; Davis, G.C. Previous Exposure to Trauma and PTSD Effects of Subsequent Trauma: Results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A. Post-traumatic stress disorder: A state-of-the-art review of evidence and challenges. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapke, U.; Schumann, A.; Rumpf, H.-J.; John, U.; Meyer, C. Post-traumatic stress disorder: The role of trauma, pre-existing psychiatric disorders, and gender. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollica, R.F.; McInnes, K.; Pool, C.; Tor, S. Dose-effect relationships of trauma to symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among Cambodian survivors of mass violence. Br. J. Psychiatry 1998, 173, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuner, F.; Schauer, M.; Karunakara, U.; Klaschik, C.; Robert, C.; Elbert, T. Psychological trauma and evidence for enhanced vulnerability for posttraumatic stress disorder through previous trauma among West Nile refugees. BMC Psychiatry 2004, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilker, S.; Pfeiffer, A.; Kolassa, S.; Koslowski, D.; Elbert, T.; Kolassa, I.-T. How to quantify exposure to traumatic stress? Reliability and predictive validity of measures for cumulative trauma exposure in a post-conflict population. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2015, 6, 28306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Takebayashi, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Horikoshi, M. Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5: Psychometric properties in a Japanese population. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 247, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, M. Social worker trauma: Building resilience in child protection social workers. Smith Coll. Stud. Soc. Work. 1998, 68, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regehr, C.; Chau, S.; Leslie, B.; Howe, P. An Exploration of Supervisor’s and Manager’s Responses to Child Welfare Reform. Adm. Soc. Work. 2002, 26, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlinghton, VA, USA; Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shimomitsu, T. The Final Development of the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire Mainly Used for Assessment of the Individuals. In Ministry for Labour Sponsored Grant for the Prevention of Work-Related Illness: The 1999 Report; The Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare: Tokyo, Japan, 2000; pp. 126–164. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi, D.; Uehara, R.; Yoshikawa, E.; Sato, G.; Ito, M.; Matsuoka, Y. Culturally sensitive and universal measure of resilience for Japanese populations: Tachikawa Resilience Scale in comparison with Resilience Scale 14-item version. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 67, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewin, C.R.; Andrews, B.; Valentine, J.D. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 748–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, E.J.; Best, S.R.; Lipsey, T.L.; Weiss, D.S. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwitz, M.J. Work-Related Trauma Effects in Child Protection Social Workers. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2006, 32, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlechild, B. The Stresses Arising from Violence, Threats and Aggression against Child Protection Social Workers. J. Soc. Work. 2005, 5, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ettorre, G.; Mazzotta, M.; Pellicani, V.; Vullo, A. Preventing and managing workplace violence against healthcare workers in Emergency Departments. Acta Biomed. 2018, 89, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge, E.A.; Austin, E.D.; Pollack, M.H. Resilience: Research evidence and conceptual considerations for posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2007, 24, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Ahn, Y.-S.; Jeong, K.-S.; Chae, J.-H.; Choi, K.-S. Resilience buffers the impact of traumatic events on the development of PTSD symptoms in firefighters. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 162, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCanlies, E.C.; Mnatsakanova, A.; Andrew, M.E.; Burchfiel, C.M.; Violanti, J.M. Positive Psychological Factors are Associated with Lower PTSD Symptoms among Police Officers: Post Hurricane Katrina. Stress Health 2014, 30, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mealer, M.; Jones, J.; Newman, J.; McFann, K.K.; Rothbaum, B.O.; Moss, M. The presence of resilience is associated with a healthier psychological profile in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses: Results of a national survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, S.K.; Sopp, M.R.; Staginnus, M.; Lass-Hennemann, J.; Michael, T. Correlates of mental health in occupations at risk for traumatization: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | n | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 43.98 | 12.34 | ||

| Years of work experience | 4.86 | 4.17 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 36 | 25.7 | ||

| Female | 104 | 74.3 | ||

| Qualification | ||||

| None | 9 | 6.4 | ||

| Welfare a | 76 | 54.3 | ||

| Psychology | 21 | 15.0 | ||

| Medical | 5 | 3.6 | ||

| Others | 12 | 8.6 | ||

| Multiple | 17 | 12.1 | ||

| Job stressors | ||||

| Job demand | 10.27 | 1.94 | ||

| Job control | 7.25 | 2.10 | ||

| Social support from supervisors | 7.79 | 2.05 | ||

| Social support from colleagues | 8.36 | 1.96 | ||

| TRS score | 44.98 | 10.01 | ||

| PCL-5 score | 10.75 | 13.17 |

| Once (a) | Two or More Times (b) | (a) + (b) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Directly experiencing the traumatic event(s) | ||||||

| 11 | 7.9 | 15 | 10.7 | 26 | 18.6 |

| 10 | 7.1 | 22 | 15.7 | 32 | 22.8 |

| 4 | 2.9 | 1 | 0.7 | 5 | 3.6 |

| Witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurred to others | ||||||

| 6 | 4.3 | 18 | 12.9 | 24 | 17.2 |

| 4 | 2.9 | 13 | 9.3 | 17 | 12.2 |

| 2 | 1.4 | 2 | 1.4 | 4 | 2.8 |

| 3 | 2.1 | 5 | 3.6 | 8 | 5.7 |

| 5 | 3.6 | 14 | 10.0 | 19 | 13.6 |

| Learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a close family member or close friend | ||||||

| 10 | 7.1 | 20 | 14.3 | 30 | 21.4 |

| 15 | 10.7 | 21 | 15.0 | 36 | 25.7 |

| 4 | 2.9 | 5 | 3.6 | 9 | 6.5 |

| Experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s) | ||||||

| 5 | 3.6 | 93 | 66.4 | 98 | 70.0 |

| 22 | 15.7 | 51 | 36.4 | 73 | 52.1 |

| 8 | 5.7 | 66 | 47.1 | 74 | 52.8 |

| Cumulative Number of Types of Work-Related Trauma Events Experienced a | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 18 | 12.9 |

| 1 | 23 | 16.4 |

| 2 | 16 | 11.4 |

| 3 | 34 | 24.3 |

| 4 | 17 | 12.1 |

| 5 | 13 | 9.3 |

| ≥6 | 19 | 13.6 |

| Univariate | Multivariate (First) | Multivariate (Second) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | 95% CI | Beta | SE | 95% CI | Beta | SE | 95% CI | |

| Age | −0.20 | 0.08 | (−0.38, −0.02) * | −0.03 | 0.10 | (−0.23, 0.16) | −0.02 | 0.09 | (−0.21, 0.17) |

| Years of work experience | −0.36 | 0.26 | (−0.89, 0.16) | −0.30 | 0.30 | (−0.91, 0.29) | −0.35 | 0.29 | (−0.93, 0.21) |

| Gender, women | −0.52 | 2.55 | (−5.57, 4.53) | −0.88 | 2.47 | (−5.77, 4.01) | −1.74 | 2.43 | (−6.55, 3.07) |

| TRS score | −0.59 | 0.10 | (−0.79, −0.39) ** | −0.60 | 0.12 | (−0.84, −0.36) ** | −0.60 | 0.11 | (−0.84, −0.36) ** |

| Qualification | |||||||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Welfare a | 7.00 | 4.59 | (−2.08, 16.09) | 4.37 | 4.48 | (−4.50, 13.25) | 5.82 | 4.38 | (−2.86, 14.50) |

| Psychology | 4.01 | 5.19 | (−6.25, 14.28) | 5.78 | 5.02 | (−4.17, 15.74) | 6.23 | 4.93 | (−3.54, 16.01) |

| Medical | −2.88 | 7.27 | (−17.27, 11.49) | 1.82 | 7.10 | (−12.23, 15.89) | 3.46 | 7.07 | (−10.54, 17.48) |

| Others | −1.38 | 5.74 | (−12.75, 9.98) | 2.41 | 5.48 | (−8.45, 13.29) | 4.08 | 5.37 | (−6.55, 14.73) |

| Multiple | 5.58 | 5.37 | (−5.04, 16.21) | 7.40 | 5.18 | (−2.87, 17.68) | 7.65 | 5.13 | (−2.50, 17.82) |

| Job stressors | |||||||||

| Job demand | 2.04 | 0.55 | (0.95, 3.13) ** | 1.09 | 0.65 | (−0.20, 2.40) | 1.15 | 0.65 | (−0.14, 2.44) |

| Job control | −0.95 | 0.52 | (−1.99, 0.08) | 0.04 | 0.61 | (−1.17, 1.25) | 0.04 | 0.58 | (−1.11, 1.21) |

| Social support from supervisors | −0.19 | 0.54 | (−1.27, 0.88) | 0.83 | 0.68 | (−0.52, 2.19) | 0.68 | 0.67 | (−0.64, 2.00) |

| Social support from colleagues | −0.85 | 0.56 | (−1.97, 0.27) | −0.30 | 0.69 | (−1.67, 1.06) | −0.25 | 0.68 | (−1.61, 1.10) |

| Type of traumatic event experienced b | |||||||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 1 | −2.84 | 3.66 | (−10.09, 4.41) | −0.43 | 3.35 | (−7.07, 6.21) | |||

| 2 | 0.51 | 3.22 | (−5.86, 6.89) | 2.52 | 2.91 | (−3.24, 8.30) | |||

| 3 | −3.98 | 6.32 | (−16.49, 8.52) | −8.31 | 5.75 | (−19.70, 3.07) | |||

| 5 | 3.88 | 4.30 | (−4.62, 12.40) | 1.53 | 3.87 | (−6.15, 9.21) | |||

| 7 | 12.29 | 5.43 | (1.53, 23.06) * | 11.96 | 4.97 | (2.11, 21.80) * | |||

| 8 | −3.30 | 3.90 | (−11.02, 4.42) | −1.65 | 3.52 | (−8.63, 5.31) | |||

| 9 | 0.75 | 3.23 | (−5.63, 7.15) | 1.74 | 2.94 | (−4.09, 7.58) | |||

| 10 | −1.17 | 2.82 | (−6.76, 4.41) | −1.31 | 2.56 | (−6.40, 3.76) | |||

| 11 | 5.52 | 5.04 | (−4.45, 15.51) | 4.46 | 4.55 | (−4.56, 13.49) | |||

| 12 | 0.93 | 2.75 | (−4.50, 6.37) | 0.27 | 2.68 | (−5.04, 5.59) | |||

| 13 | −0.13 | 2.49 | (−5.07, 4.81) | −0.84 | 2.42 | (−5.64, 3.96) | |||

| 14 | 1.53 | 2.52 | (−3.47, 6.53) | 1.84 | 2.36 | (−2.83, 6.52) | |||

| Cumulative number of types of traumatic events experienced | |||||||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 1 | 1.93 | 4.14 | (−6.26, 10.13) | 3.22 | 3.72 | (−4.14, 10.59) | |||

| 2 | 0.54 | 4.52 | (−8.40, 9.50) | −1.55 | 4.15 | (−9.77, 6.66) | |||

| 3 | 0.19 | 3.84 | (−7.39, 7.79) | 0.40 | 3.70 | (−6.93, 7.74) | |||

| 4 | −0.30 | 4.45 | (−9.11, 8.51) | 2.04 | 4.42 | (−6.71, 10.81) | |||

| 5 | 4.11 | 4.79 | (−5.37, 13.59) | 6.51 | 4.64 | (−2.68, 15.70) | |||

| ≥6 | 8.00 | 4.33 | (−0.56, 16.57) | 8.24 | 4.20 | (−0.07, 16.56) | |||

| R2 | 0.36 ** | 0.34 ** | |||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.23 ** | 0.23 ** | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kataoka, M.; Nishi, D. Association between Work-Related Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms among Child Welfare Workers in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073541

Kataoka M, Nishi D. Association between Work-Related Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms among Child Welfare Workers in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(7):3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073541

Chicago/Turabian StyleKataoka, Mayumi, and Daisuke Nishi. 2021. "Association between Work-Related Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms among Child Welfare Workers in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 7: 3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073541

APA StyleKataoka, M., & Nishi, D. (2021). Association between Work-Related Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms among Child Welfare Workers in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073541