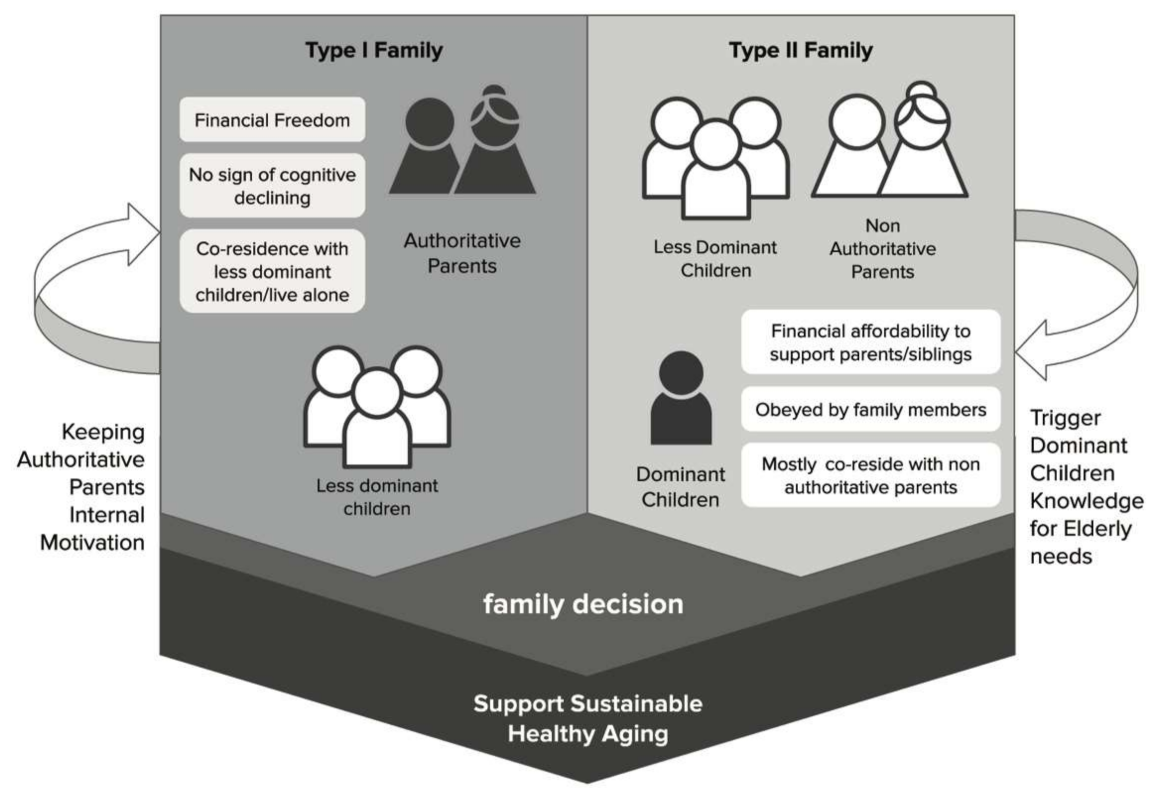

Authoritative Parents and Dominant Children as the Center of Communication for Sustainable Healthy Aging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Filial Piety in Indonesia

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methods

- basic value/norms/role ethics between the respondents towards the elderly;

- the interactivity between the respondents towards the elderly;

- differences between the value/norm/role ethics and interaction between the respondents towards the elderly.

3.2. Sampling Structures

- Living arrangement: Co-residence and not co-residence with the elderly

- Area of living: Urban and rural area.

- Major ethnicities in Indonesia: such as Javanese, Sundanese, Tionghoa (Chinese Indonesian), Batak, or Balinese people.

- Inclusion criterion: the respondent should be an Independent Indonesian adult, as this stage of age arguably already implements filial piety as part of their role ethics, so the gap in the intergenerational elderly will be more likely able to reach the age of 60. People in this group already have firsthand experience of intensely interacting with the elderly, which act as the older generation of the respondents.

- Exclusion criterion: (1) if the elderly in the family are younger than 60 years old; (2) if the experience was more than ten years ago (the elderly in the family already passed away more than ten years ago), as this would create deviation between experience and memory recollection; (3) if the respondents paid for taking care of the elderly.

3.3. Data Analysis

- Transcription in Bahasa Indonesia. All of the interviews were done in Bahasa Indonesia and local dialect, and the coding was transcribed verbatim in Bahasa Indonesia to avoid decontextualization.

- Familiarization of the data and identifying items of potential interest. After transcription, the data were familiarized by the researcher, and if several ambiguities were found, the researcher asked for confirmation on the true meaning of the respondent’s statement and rechecked the transcription with other co-researchers.

- Classification of the respondent’s demographic information. Demographic classification was predetermined prior to the interviews. Besides the sampling structures differentiating living arrangement (co-residence/not co-residence) and area of living (urban–rural), there was also other demographic classification based on the elderly (relationship, independency, age, financial status, living children, residencies ownership, mobility, supported, and living arrangement of the elderly) and demographic classification based on respondents (age, child status in the family, marital status, socio-economic status, highest education, and sex). A detailed description of demographic data collection is presented in detail in Table 1.

- Generating initial coding without considering the classification made. Initial coding was generated based on the respondent’s overall expression to represent a broader filial piety context.

- Categorizing the themes into the 10-item Contemporary Filial Piety Scale (CFPS). The 10-item CFPS is a modified instrument to measure experience and practice of filial piety down from three to two factors: Pragmatic Obligation and Compassionate Reverence. These are proven to be data-driven, efficient, and straightforward, with strong psychometric properties to assess contemporary filial piety with an internal consistency of 0.88 and 0.95 goodness of fit [34]. The constructs were divided into 10 items as follows. There were six items to construct pragmatic obligations: (1) arranging care for parents when they can no longer care for themselves; (2) providing financial subsistence to parents when they can no longer financially support themselves; (3) arranging an appropriate treatment for parents when they fall ill; (4) attending parents’ funerals no matter where one is; (5) visit parents regularly if one is not living with them; (6) being thankful for parents’ nurturing. The four items of the compassionate reverence construct consist of (1) trying one’s best to achieve parents’ expectations; (2) always being polite when talking to parents; (3) trying one’s best to complete parents’ unachieved goals; and (4) always caring about parents’ well-being. By coding participants’ expressions, we would like to make sure that Indonesian society adopts these values. The filled construct gathered by initial coding reveals whether the concept of filial piety is implemented wholly or partially in the Indonesian family and society. Thus, this coding became the first validation of this study; however, it was used by construct to measure the scales. Therefore, we did not ask the participants to fill the instrument.

- Cross-tabulating categorized answers to demographic information. Cross-tabulating participant’s answers was done based on demographic information to contrast specific expressions or representations generally.

- Clustering the categorized answers into themes. Themes were generated after clustering the participants’ categorization, so we were able to articulate the construction between the categories into a sound report.

- Mapping the relations between themes.

- Drawing conclusions based on unique answers to the phenomenon of the sedentary lifestyle of the elderly and whether or not it is related to how the intergenerational interaction is implemented in everyday life.

- Translating the related transcription into English for making the report.

4. Results

4.1. Ten-Item Contemporary Filial Piety Scale Result

4.2. Categorization and Themes

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, G.W. Contemporary Demographic Transformations in China, India and Indonesia. Demographic Transformation and Socio-Economic Development. In Ageing in China, India and Indonesia: An Overview; Guilmoto, C.Z., Jones, G.W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, P. A Population Projection for Indonesia, 2010–2035. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2014, 50, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indonesia Health Profile 2018; 351.077 Ind p; Pusat Data dan Informasi Kementrian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia): Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019.

- Gil-Lacruz, A.; Gil-Lacruz, M.; Saz-Gil, M.I. Socially Active Aging and Self-Reported Health: Building a Sustainable Solidarity Ecosystem. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briede-Westermeyer, J.C.; Pacheco-Blanco, B.; Luzardo-Briceño, M.; Pérez-Villalobos, C. Mobile Phone Use by the Elderly: Relationship between Usability, Social Activity, and the Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazuleviciute-Vileniske, I.; Seduikyte, L.; Teixeira-Gomes, A.; Mendes, A.; Borodinecs, A.; Buzinskaite, D. Aging, Living Environment, and Sustainability: What Should be Taken into Account? Sustainability 2020, 12, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dėdelė, A.; Miškinytė, A.; Andrušaitytė, S.; Bartkutė, Ž. Perceived Stress among Different Occupational Groups and the Interaction with Sedentary Behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Ding, C.; Gong, W.; Yuan, F.; Ma, Y.; Feng, G.; Song, C.; Liu, A. The Relationship between Leisure-Time Sedentary Behaviors and Metabolic Risks in Middle-Aged Chinese Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.T.; Chen, M.; Ho, C.C.; Lee, T.S. Relationships among Leisure Physical Activity, Sedentary Lifestyle, Physical Fitness, and Happiness in Adults 65 Years or Older in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.L.; Cattell, R.B. Age differences in fluid and crystallized intelligence. Acta Psychol. 1967, 26, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wianto, E.; Chen, Y.-H.; Chang, C.-Y.; Kaburuan, E.R.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-H. Enhancing Quality of Life Based on Physical Activity for Indonesian Elderly: A Preliminary Study for Design Recommendation. In Proceedings of the CONMEDIA 2019, Kuta, Bali, Indonesia, 9–11 October 2019; Curran Associates, Inc.: Kuta, Bali, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wianto, E.; Chen, C.-H.; Defi, I.R.; Sartika, E.M.; Hangkawidjaja, A.D.; Lin, Y.-C. Understanding Interactivity for the Needs of the Elderly’s Strength Training at Nursing Home in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the DRS2020, Synergy, Brisbane, Australia, 11–14 August 2020; Tsekleves, E., Ed.; Design Research Society: Brisbane, Australia, 2020; p. 1408. [Google Scholar]

- Setiyani, R.; Windsor, C. Filial Piety: From the Perspective of Indonesian Young Adults. Nurse Media J. Nurs. 2019, 9, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll-Dayton, B.; Saengtienchai, C. Respect for the Elderly in Asia: Stability and Change. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1999, 48, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, K.H.; Bedford, O. Filial belief and parent-child conflict. Int. J. Psychol. 2004, 39, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, N. The practice of filial piety and its impact on long-term care policies for elderly people in Asian Chinese communities. Asian J. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2006, 1, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, C.G. Bystander attitudes toward parents? The perceived meaning of filial piety among Koreans in Australia, New Zealand and Korea. Australas. J. Ageing 2016, 35, E25–E29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guang, X. The Teaching and Practice of Filial Piety in Buddhism. J. Law Relig. 2016, 31, 212–226. [Google Scholar]

- Pharr, J.R.; Francis, C.D.; Terry, C.; Clark, M.C. Culture, Caregiving, and Health: Exploring the Influence of Culture on Family Caregiver Experiences. ISRN Public Health 2014, 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.W.; Long, Y.; Essex, E.L.; Sui, Y.; Gao, L. Elderly Chinese and Their Family Caregivers’ Perceptions of Good Care: A Qualitative Study in Shandong, China. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2012, 55, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadar, K.S.; Francis, K.; Sellick, K. Ageing in Indonesia—Health Status and Challenges for the Future. Ageing Int. 2013, 38, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witoelar, F. Household Dynamics and Living Arrangements of the Elderly in Indonesia: Evidence from a Longitudinal Survey. In National Research Council (US) Panel on Policy Research and Data Needs to Meet the Challenge of Aging in Asia; Smith, J.P., Majmundar, M., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, M.S.; Liew, C.V.; Holloway, B.; McKinnon, S.; Little, T.; Cronan, T.A. Honor Thy Parents: An Ethnic Multigroup Analysis of Filial Responsibility, Health Perceptions, and Caregiving Decisions. Res. Aging 2015, 38, 665–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, M.; Maruyama, S. Does Coresidence Improve an Elderly Parent’s Health? J. Appl. Econom. 2014, 29, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggles, S.; Heggeness, M. Intergenerational Coresidence in Developing Countries. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2008, 34, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, A.; Mcdonald, P.; Utomo, I.; Cahyadi, N.; Sparrow, R. Social engagement and the elderly in rural Indonesia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 229, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bern-Klug, M. I should be doing more for my parent: Chinese adult children’s worry about performance in providing care for their oldest-old parents. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarberg, K.; Kirkman, M.; Lacey, S.D. Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Human Reprod. 2016, 31, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitto, S.C.; Chesters, J.; Grbich, C. Quality in qualitative research. Med. J. Aust. 2008, 188, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Government Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia on Efforts to Increase the Social Welfare of the Elderly (Peraturan Pemerintah Republik Indonesia tentang Pelaksanaan Upaya Peningkatan Kesejahteraan Sosial Lanjut Usia). 2004. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/66188 (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Li, T.; Wu, B.; Yi, F.; Wang, B.; Baležentis, T. What Happens to the Health of Elderly Parents When Adult Child Migration Splits Households? Evidence from Rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Act of Republic of Indonesia on Village (Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia tentang Desa). 2014, Volume 6. Available online: https://www.dpr.go.id/dokjdih/document/uu/UU_2014_6.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Lum, T.Y.; Yan, E.C.; Ho, A.H.; Shum, M.H.; Wong, G.H.; Lau, M.M.; Wang, J. Measuring Filial Piety in the 21st Century: Development, Factor Structure, and Reliability of the 10-Item Contemporary Filial Piety Scale. Appl. Gerontol. 2015, 35, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyett, P.M. Validation of Qualitative Research in the “Real World”. Qual. Health Res. 2003, 13, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Gu, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Tian, D. Does an Empty Nest Affect Elders’ Health? Empirical Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N. Parenting Style and Its Correlates, ED427896 ed.; ERIC Publications: Washington DC, USA, 1999; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Q.; Treiman, D.J. Living Arrangements of the Elderly in China and Consequences for Their Emotional Well-being. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 47, 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.S.; Kim, S.J.; Shin, H.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, S.W.; Yoon, J.S. Comparison of depression between elderly living alone and those living with a spouse. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, S394–S395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Wang, D.; Guerrien, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis on basic psychological need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in later life: Contributions of self-determination theory. Psych. J. 2020, 9, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. Family support or social support? The role of clan culture. J. Popul. Econ. 2019, 32, 529–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, L.A.; Cobb-Clark, D. Do Coresidency and Financial Transfers from the Children Reduce the Need for Elderly Parents to Works in Developing Countries? J. Popul. Econ. 2008, 21, 1007–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichberg, H.; Kosiewicz, J.; Contiero, D. Pilgrimage: Intrinsic Motivation and Active Behavior in the Eldery. Phys. Cult. Sport. Stud. Res. 2017, 75, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kivipelto, M.; Mangialasche, F.; Ngandu, T. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lottum, J.v.; Marks, D. The determinants of internal migration in a developing country: Quantitative evidence for Indonesia, 1930–2000. Appl. Econ. 2012, 44, 4485–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speare, A.; Harris, J. Education, Earnings, and Migration in Indonesia. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1986, 34, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliki. Health Card and Health Care Facilities Demand Among the Indonesian Elderly. Singap. Econ. Rev. 2008, 53, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, B. Solidarity and care as relational practices. Bioethics 2018, 32, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szinovacz, M.E.; Davey, A. The division of parent care between spouses. Ageing Soc. 2008, 28, 571–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammohan, A.; Magnani, E. Modelling the influence of caring for the elderly on migration: Estimates and evidence from Indonesia. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2012, 48, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, S.R.; Krieger, J.L.; Stellefson, M.L. The Influence of eHealth Literacy on Perceived Trust in Online Health Communication Channels and Sources. J. Health Commun. 2017, 22, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.; McEwan, B. Distinguishing technologies for social interaction: The perceived social affordances of communication channels scale. Commun. Monogr. 2017, 84, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekleves, E.; Cooper, R. Design Research Opportunities in the Internet of Health Things. In Proceedings of the DRS 2018, Design as a Catalyst for Change, Limerick, Ireland, 25–28 June 2018; Bohemia, E., Storni, C., Leahy, K., McMahon, M., Lloyd, P., Eds.; Design Research Society: Limerick, Ireland, 2018; pp. 2366–2379. [Google Scholar]

- Santana-Mancilla, P.C.; Anido-Rifón, L.E.; Contreras-Castillo, J.; Buenrostro-Mariscal, R. Heuristic Evaluation of an IoMT System for Remote Health Monitoring in Senior Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-J.; Tasi, W.-C.; Yang, W.-L.; Guo, J.-L. How to help older adults learn new technology? Results from a multiple case research interviewing the internet technology instructors at the senior learning center. Comput. Educ. 2019, 129, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaval, L.; Li, Y.; Johnson, E.J.; Weber, E.U. Complementary Contributions of Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence to Decision Making Across the Life Span. In Aging and Decision Making; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar]

| No | Classification Attributes | Class | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Living area | rural; urban | Living area of the elderly. |

| 2 | Elderly relationship with the respondents | parents; parents-in-law; unmarried aunt; and grandparents | Elderly relationship with the respondents. |

| 3. | Elderly dependency | independent; partly dependent; and totally dependent | Dependency status of the elderly according to the respondents.a |

| 4 | Elderly Age | 66–65; 66–70; 71–75; 76–89; 81–85; and 86–90 | Elderly age range. |

| 5 | Elderly financial status | financially independent; still have income, and dependent | Financial ability of the elderly.b |

| 6 | Children of the elderly (number) | 1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; and 7 | Relates to how many children alive they still have. |

| 7 | Elderly co-residency status | with children; without children c | The co-residency status is not always with the respondents. |

| 9 | Elderly mobility | able to do independent mobility; not able to do independent mobility | Mobility capacity of the elderly. |

| 10 | Elderly supported by | all children; available/willing children; and no support | Related to who supports the elderly.d |

| 11 | Respondents’ living arrangement with the elderly | respondents living arrangement with the elderly: co-residency; and non-co-residency | It is separated by the number 7 (elderly co-residency status). |

| 12 | Respondents’ age range | 26–30; 31–35; 36–40; 41–45; 46–50; and 51–55 | Age range of the respondents. |

| 13 | Respondents’ child status in the family | only child; eldest; middle; and youngest | Respondents’ child status in the family. |

| 14 | Respondents’ marital status | married; un-married | Respondents’ marital status. |

| 15 | Respondents socio-economic status | 1 to 10 (1 for not enough, 10 for more than enough) | Subjective socio-economic of the respondents. |

| 16 | Respondents’ highest education | Bachelor’s degree; Master’s degree; doctoral degree. | Highest education achieved by the respondents. |

| 17 | Respondents’ sex | female; male | Respondents’ sex. |

| No | Categories | Description | Subcategories |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Related to older people (in general) | Opinion in a broader context related to how younger and older generations should act. In these categories, older generation includes non-familial elderly. | Brain activation for the elderly; judgment of elderly’s physical condition; societal power through blood relation; parents cannot compare with anyone; independent and capable younger people; younger people needs to act less superior towards the elderly |

| 2 | Relationship between parents—children | Opinion related to how the respondents in their role of children state their relationship with their parents exclusively. | Affordability; decency; emotionally; reciprocity; respect |

| 3 | Children’s supported to | Opinion related to how, when, and why the respondents support their parents | How; when; why. |

| 4 | Factors influence relationship | All of the factors can comprise the baseline of their thought and act. | Cultural value (including religious value) and personal value |

| 5 | Respondents’ point of view | Specific opinion regarding anything explaining their relationship to supporting their parents. Some sort of reason on how they thought or act towards their parents. | Blessing from the elderly; changing priority; I do what I like people do to me; I will be disappointed if I can’t do it; reason to keep the ideal norm; appropriate to pay respect to parents; and tolerance between siblings |

| 6 | Wrongdoing to my parents | Specific opinion regarding respondent’s guilt for the action they did to their parents. | I’m not doing what supposed to do; I don’t feel like (to do) it; I don’t have enough knowledge before; I failed the manner; I failed to calm him down; I failed to give what best for him; I lied to them; I think that it is not important; and my parents think differently |

| 7 | Related to elderly physical activities | Specific opinions from the respondents related to physical activities of the elderly people. | because they are old; they need to have rest; disease; the elderly are not supposed to/not allowed to do it; full dependency of the elderly; physical assist for those who need it (not only to elderly); physically independent |

| No | Item | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | STRENGTH |

|

| 2 | WEAKNESS |

|

| 3 | OPPORTUNITY |

|

| 4 | THREAT |

|

| No | Item | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | STRENGTH |

|

| 2 | WEAKNESS |

|

| 3 | OPPORTUNITY |

|

| 4 | THREAT |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wianto, E.; Sarvia, E.; Chen, C.-H. Authoritative Parents and Dominant Children as the Center of Communication for Sustainable Healthy Aging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063290

Wianto E, Sarvia E, Chen C-H. Authoritative Parents and Dominant Children as the Center of Communication for Sustainable Healthy Aging. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063290

Chicago/Turabian StyleWianto, Elizabeth, Elty Sarvia, and Chien-Hsu Chen. 2021. "Authoritative Parents and Dominant Children as the Center of Communication for Sustainable Healthy Aging" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063290

APA StyleWianto, E., Sarvia, E., & Chen, C.-H. (2021). Authoritative Parents and Dominant Children as the Center of Communication for Sustainable Healthy Aging. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063290