Social Ecological Model of Problem Gambling: A Cross-National Survey Study of Young People in the United States, South Korea, Spain, and Finland

Abstract

1. Introduction

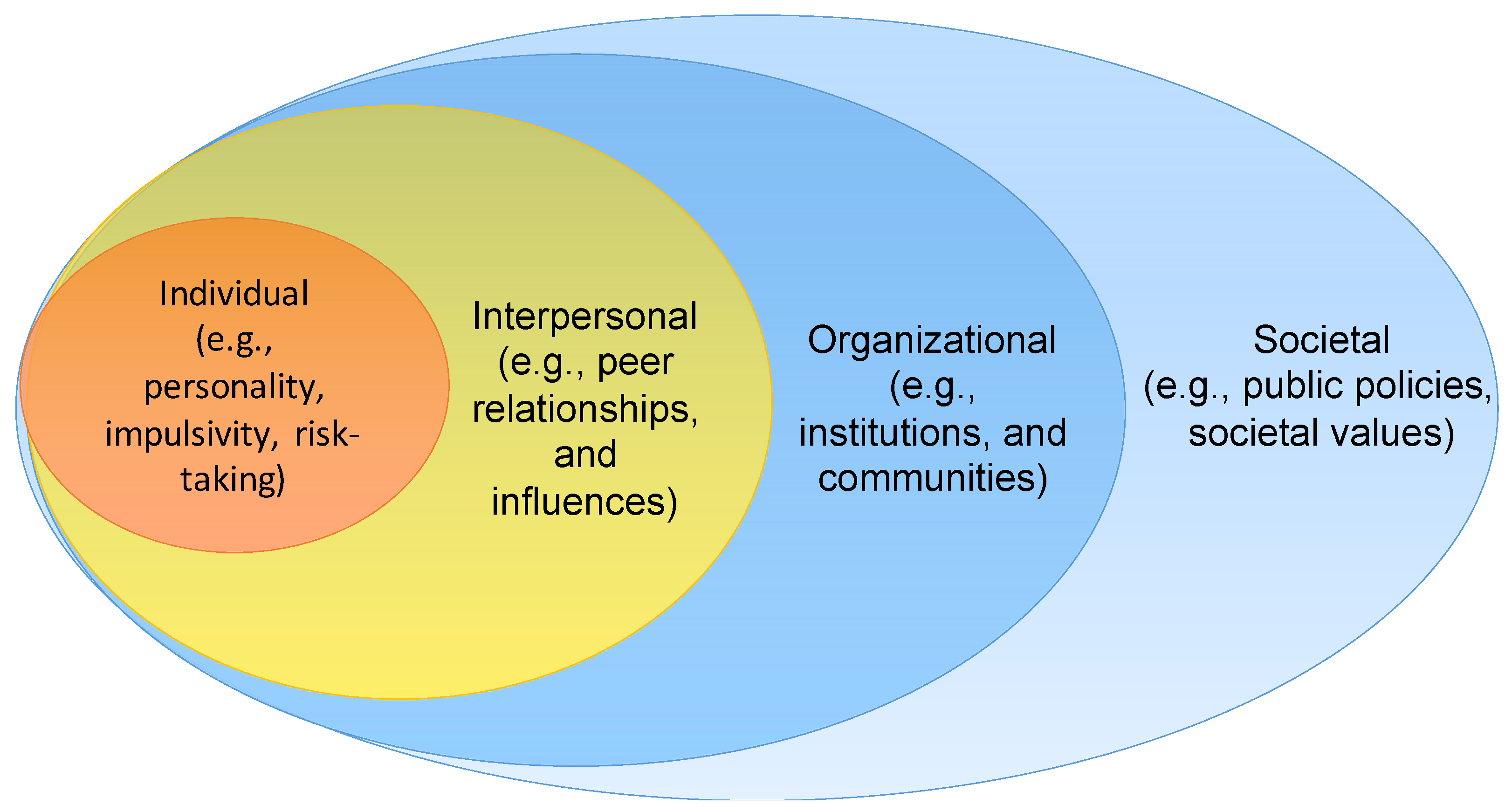

1.1. Social Ecological Model for Gambling Problems

1.2. Evidence on Problem Gambling in Different Spheres

1.3. This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Problem Gambling

2.2.2. Intrapersonal Sphere

2.2.3. Interpersonal Sphere

2.2.4. Organizational Sphere

2.2.5. Societal Sphere

2.3. Statistical Modelling

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Finland | United States | South Korea | Spain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 21.29 | 20.05 | 20.61 | 20.07 |

| Male (%) | 50.00 | 49.83 | 49.58 | 51.24 |

| University degree (%) | 13.42 | 20.38 | 28.1 | 28.38 |

| Occupational status | ||||

| Student (%) | 64.33 | 53.96 | 67.53 | 58.33 |

| Working (%) | 20.33 | 34.16 | 21.82 | 31.36 |

| Unemployed/other (%) | 15.34 | 11.88 | 10.65 | 10.31 |

| Born abroad (%) | 4.08 | 4.54 | 0.59 | 12.21 |

| Lives with parents (%) | 35.92 | 51.16 | 81.80 | 66.67 |

| Significant financial support from parents or relatives (%) * | 17.56 | 35.47 | 65.90 | 58.42 |

Appendix B

| Linear | Logistic | ZINB | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | OR | 95% | CI | p | IRR | 95% | CI | p | |

| Intrapersonal | ||||||||||

| Male gender | 0.11 | <0.001 | 1.96 | 1.36 | 2.82 | <0.001 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 1.40 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.145 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 1.07 | 0.725 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.039 |

| Impulsivity | 0.10 | <0.001 | 1.33 | 1.19 | 1.48 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.11 | <0.001 |

| Self-esteem | −0.03 | 0.042 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.99 | 0.030 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.005 |

| Risk-taking | 0.08 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 0.99 | 1.17 | 0.099 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 0.007 |

| Interpersonal | ||||||||||

| Perceived social support (high) | −0.07 | <0.001 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 1.04 | 0.076 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.98 | 0.018 |

| Belonging offline | −0.02 | 0.178 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 1.01 | 0.080 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.004 |

| Belonging online | 0.03 | 0.052 | 1.08 | 0.99 | 1.17 | 0.068 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 0.013 |

| Social media identity bubble | 0.03 | 0.029 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 1.26 | 0.035 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 0.074 |

| Conformity to group norm | 0.04 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 0.92 | 1.27 | 0.349 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 0.016 |

| Organizational | ||||||||||

| Consumer debt | 0.11 | <0.001 | 2.91 | 2.00 | 4.23 | <0.001 | 1.23 | 1.11 | 1.36 | <0.001 |

| Online casino participation | 0.22 | <0.001 | 2.56 | 1.58 | 4.14 | <0.001 | 1.20 | 1.09 | 1.32 | <0.001 |

| Online gambling comm. partic. | 0.28 | <0.001 | 2.68 | 1.70 | 4.20 | <0.001 | 1.39 | 1.26 | 1.54 | <0.001 |

| Pop-up gambling adv. (ref. never) | ||||||||||

| Max monthly | 0.03 | 0.014 | 1.39 | 0.67 | 2.90 | 0.381 | 1.02 | 0.88 | 1.19 | 0.748 |

| Weekly | 0.09 | <0.001 | 2.41 | 1.13 | 5.14 | 0.022 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 1.36 | 0.047 |

| Societal | ||||||||||

| Country difference (ref. Spain) Finland | 0.00 | 0.929 | 0.76 | 0.48 | 1.20 | 0.237 | 1.06 | 0.94 | 1.18 | 0.348 |

| The U.S. | −0.05 | 0.003 | 0.80 | 0.52 | 1.22 | 0.295 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 1.03 | 0.135 |

| South Korea | −0.06 | <0.001 | 0.66 | 0.38 | 1.13 | 0.132 | 1.07 | 0.97 | 1.18 | 0.195 |

| Model N | 4546 * | 4816 | 4816 | |||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 38% | |||||||||

| Pseudo adj. R2 (McFadden) | 24% | 42% | ||||||||

References

- Calado, F.; Griffiths, M.D. Problem gambling worldwide: An update and systematic review of empirical research (2000–2015). J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 592–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calado, F.; Alexandre, J.; Griffiths, M.D. Prevalence of adolescent problem gambling: A systematic review of recent research. J. Gambl. Stud. 2017, 33, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberg, R.; Gupta, R.; Griffiths, M.D.; Olason, D.; Delfabbro, P.H. An international perspective on youth gambling prevalence studies. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2010, 22, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszczynski, A.; Nower, L. A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction 2002, 97, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudriaan, A.E.; Slutske, W.S.; Krull, J.L.; Sher, K.J. Longitudinal patterns of gambling activities and associated risk factors in college students. Addiction 2009, 104, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livazović, G.; Bojčić, K. Problem gambling in adolescents: What are the psychological, social and financial consequences? BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfabbro, P. Problem and pathological gambling: A conceptual review. J. Gambl. Bus. Econ. 2013, 7, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainsbury, S.M.; Russell, A.; Wood, R.; Hing, N.; Blaszczynski, A. How risky is Internet gambling? A comparison of subgroups of Internet gamblers based on problem gambling status. New Media Soc. 2015, 17, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H. Early exposure to digital simulated gambling: A review and conceptual model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirola, A.; Savela, N.; Savolainen, I.; Kaakinen, M.; Oksanen, A. The Role of Virtual Communities in Gambling and Gaming Behaviors: A Systematic Review. J. Gambl. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakinen, M.; Sirola, A.; Savolainen, I.; Oksanen, A. Young people and gambling content in social media: An experimental insight. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020, 39, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Kaptsis, D.; Zwaans, T. Adolescent simulated gambling via digital and social media: An emerging problem. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirola, A.; Kaakinen, M.; Oksanen, A. Excessive gambling and online gambling communities. J. Gambl. Stud. 2018, 34, 1313–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keipi, T.; Näsi, M.; Oksanen, A.; Räsänen, P. Online Hate and Harmful Content: Cross-National Perspectives; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. A Dynamic Theory of Personality. Selected Papers; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1935; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory. In Six Theories of Child Development: Revised Formulations and Current Issues; Vasta, R., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 1992; pp. 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. Read. Dev. Child. 1994, 2, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, D. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.C.; Stjepanović, D.; Lim, C.; Sun, T.; Anandan, A.S.; Connor, J.P.; Gartner, C.; Hall, W.D.; Leung, J. Gateway or common liability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of adolescent e-cigarette use and future smoking initiation. Addiction 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenewald, P.J.; Remer, L.G.; LaScala, E.A. Testing a social ecological model of alcohol use: The California 50-city study. Addiction 2014, 109, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, H.-J.; Hove, T. Determinants of underage college student drinking: Implications for four major alcohol reduction strategies. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayberry, M.L.; Espelage, D.L.; Koenig, B. Multilevel modeling of direct effects and interactions of peers, parents, school, and community influences on adolescent substance use. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 1038–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, C.M.; Gilreath, T.D.; Aklin, W.M.; Brex, R.A. Social-ecological influences on patterns of substance use among non-metropolitan high school students. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 45, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.R.; Creasy, S.L.; Mair, C.F.; Burke, J.G. Drivers of opioid use in Appalachian Pennsylvania: Cross-cutting social and community-level factors. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2020, 78, 102706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, S.; Logie, C.H.; Grosso, A.; Wirtz, A.L.; Beyrer, C. Modified social ecological model: A tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, D.; Barnes, A.; Papageorgiou, A.; Hadwen, K.; Hearn, L.; Lester, L. A social–ecological framework for understanding and reducing cyberbullying behaviours. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 23, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.; Binde, P.; Clark, L.; Hodgins, D.; Korn, D.; Pereira, A.; Quilty, L.; Thomas, A.; Volberg, R.; Walker, D.; et al. Conceptual Framework of Harmful Gambling: An International Collaboration Revised Edition; Gambling Research Exchange Ontario (GREO): Guelph, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbrecht, M.; Baxter, D.; Abbott, M.; Binde, P.; Clark, L.; Hodgins, D.C.; Manitowabi, D.; Quilty, L.; SpÅngberg, J.; Volberg, R.; et al. The Conceptual Framework of Harmful Gambling: A revised framework for understanding gambling harm. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reith, G. Beyond addiction or compulsion: The continuing role of environment in the case of pathological gambling. Addiction 2012, 107, 1736–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orford, J. Excessive Appetites: A Psychological View of Addictions, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- West, R.; Brown, J. Theory of Addiction, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, A. Deleuze and the theory of addiction. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2013, 45, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, N.A.; Merkouris, S.S.; Greenwood, C.J.; Oldenhof, E.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Youssef, G.J. Early risk and protective factors for problem gambling: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 51, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dussault, F.; Brendgen, M.; Vitaro, F.; Wanner, B.; Tremblay, R.E. Longitudinal links between impulsivity, gambling problems and depressive symptoms: A transactional model from adolescence to early adulthood. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slutske, W.S.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Poulton, R. Personality and problem gambling: A prospective study of a birth cohort of young adults. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, A.; Aaltonen, M.; Majamaa, K.; Rantala, K. Debt problems, home-leaving, and boomeranging: A register-based perspective on economic consequences of moving away from parental home. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthy, S.L.; Jonkman, J.; Blinn-Pike, L. Sensation-seeking, risk-taking, and problematic financial behaviors of college students. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2010, 31, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinn-Pike, L.; Worthy, S.L.; Jonkman, J.N. Adolescent gambling: A review of an emerging field of research. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 47, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canale, N.; Vieno, A.; Lenzi, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Borraccino, A.; Lazzeri, G.; Lemma, P.; Scacchi, L.; Santinello, M. Income inequality and adolescent gambling severity: Findings from a large-scale Italian representative survey. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoon, K.K.; Gupta, R.; Derevensky, J.L. Psychosocial variables associated with adolescent gambling. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2004, 18, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, N.M.; Weiss, L. Social support is associated with gambling treatment outcomes in pathological gamblers. Am. J. Addict. 2009, 18, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgar, F.J.; Canale, N.; Wohl, M.J.; Lenzi, M.; Vieno, A. Relative deprivation and disordered gambling in youths. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinaro, S.; Canale, N.; Vieno, A.; Lenzi, M.; Siciliano, V.; Gori, M.; Santinello, M. Country-and individual-level determinants of probable problematic gambling in adolescence: A multi-level cross-national comparison. Addiction 2014, 109, 2089–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, S.; Benedetti, E.; Scalese, M.; Bastiani, L.; Fortunato, L.; Cerrai, S.; Canale, N.; Chomynova, P.; Elekes, Z.; Feijão, F.; et al. Prevalence of youth gambling and potential influence of substance use and other risk factors throughout 33 European countries: First results from the 2015 ESPAD study. Addiction 2018, 113, 1862–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, I.; Sirola, A.; Kaakinen, M.; Oksanen, A. Peer group identification as determinant of youth behavior and the role of perceived social support in problem gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 2019, 35, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakinen, M.; Sirola, A.; Savolainen, I.; Oksanen, A. Shared identity and shared information in social media: Development and validation of the identity bubble reinforcement scale. Media Psychol. 2020, 23, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, I.; Kaakinen, M.; Sirola, A.; Koivula, A.; Hagfors, H.; Zych, I.; Paek, H.-J.; Oksanen, A. Online Relationships and Social Media Interaction in Youth Problem Gambling: A Four-Country Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisel, M.K.; Goodie, A.S. Descriptive and injunctive social norms’ interactive role in gambling behavior. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derevensky, J.L.; Gainsbury, S.M. Social casino gaming and adolescents: Should we be concerned and is regulation in sight? Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2016, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, A.; Savolainen, I.; Sirola, A.; Kaakinen, M. Problem gambling and psychological distress: A cross-national perspective on the mediating effect of consumer debt and debt problems among emerging adults. Harm Reduct. J. 2018, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, A.; Widinghoff, C. Over-Indebtedness and Problem Gambling in a General Population Sample of Online Gamblers. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarbanel, B.; Gainsbury, S.M.; King, D.; Hing, N.; Delfabbro, P.H. Gambling games on social platforms: How do advertisements for social casino games target young adults? Policy Internet 2017, 9, 184–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binde, P. Gambling Advertising: A Critical Research Review; Responsible Gambling Trust: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parke, A.; Harris, A.; Parke, J.; Rigbye, J.; Blaszczynski, A. Responsible marketing and advertising in gambling: A critical review. J. Gambl. Bus. Econ. 2014, 8, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newall, P.W.; Moodie, C.; Reith, G.; Stead, M.; Critchlow, N.; Morgan, A.; Dobbie, F. Gambling marketing from 2014 to 2018: A literature review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2019, 6, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.M.; Hing, N.; Browne, M.; Rawat, V. Are direct messages (texts and emails) from wagering operators associated with betting intention and behavior? An ecological momentary assessment study. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J.; Lee, C.K.; Back, K.J. The prevalence and nature of gambling and problem gambling in South Korea. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D.L.; Russell, A.; Hing, N. Adolescent Land-Based and Internet Gambling: Australian and International Prevalence Rates and Measurement Issues. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2020, 7, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPAD Group. ESPAD Report 2019: Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs; EMCDDA Joint Publications, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: http://www.espad.org/sites/espad.org/files/2020.3878_EN_04.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 0-7456-0665-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera, M. The ‘Southern model’ of welfare in social Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 1996, 6, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Value Survey. The Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural Map—World Values Survey 7. [Provisional Version]. 2020. Available online: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/ (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Inglehart, R. Cultural Evolution: People’s Motivations Are Changing, and Reshaping the World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, E.; Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Triandis, H.C. The shifting basis of life satisfaction judgments across cultures: Emotions versus norms. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H. Collectivism and Individualism: Cultural and Psychological Concerns. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 4, pp. 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirola, A.; Kaakinen, M.; Savolainen, I.; Paek, H.J.; Zych, I.; Oksanen, A. Online Identities and Social Influence in Social Media Gambling Exposure: A Four-Country Study on Young People. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welte, J.W.; Barnes, G.M.; Tidwell, M.C.; Hoffman, J.H.; Wieczorek, W.F. Gambling and Problem Gambling in the United States: Changes Between 1999 and 2013. J. Gambl. Stud. 2015, 31, 695–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammi, T.; Castrén, S.; Lintonen, T. Gambling in Finland: Problem gambling in the context of a national monopoly in the European Union. Addiction 2015, 110, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Granero, R.; Menchón, J.M. Gambling in Spain: Update on experience, research and policy. Addiction 2014, 109, 1595–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Ok, J.S.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.S. The Gambling Factors Related with the Level of Adolescent Problem Gambler. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J.; Volberg, R.A.; Stevens, R.M.G. The Population Prevalence of Problem Gambling: Methodological Influences, Standardized Rates, Jurisdictional Differences, and Worldwide Trends. 2012. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10133/3068 (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Salonen, A.; Lind, K.; Hagfors, H.; Castrén, S.; Kontto, J. Rahapelaaminen, Peliongelmat ja Rahapelaamiseen Liittyvät Asenteet ja Mielipiteet Vuosina 2007–2019: Suomalaisten Rahapelaaminen 2019; Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare: Helsinki, Finland, 2020; ISBN 978-952-343-594-0. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Observatory of Drugs and Addictions and Government Delegation for the National Drugs Plan. Adicciones Comportamentales; Ministerio de Sanidad: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://pnsd.sanidad.gob.es/eu/profesionales/sistemasInformacion/sistemaInformacion/pdf/2019_Informe_adicciones_comportamentales_2.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Chóliz, M.; Lamas, J. ¡ Hagan juego, menores! Frecuencia de juego en menores de edad y su relación con indicadores de adicción al juego. Rev. Esp. Drogodepend. 2017, 42, 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Yáñez, J.A.; Lalanda Fernández, C. Anuario del Juego en España 2020; Instituto de Política y Gobernanza de la Universidad Carlos III y CEJUEGO: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: http://cejuego.com/documentacion/files/Anuario%20del%20Juego%20en%20Espa%C3%B1a%202020.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- González-Roz, A.; Fernández-Hermida, J.R.; Weidberg, S.; Martínez-Loredo, V.; Secades-Villa, R. Prevalence of Problem Gambling among Adolescents: A Comparison across Modes of Access, Gambling Activities, and Levels of Severity. J. Gambl. Stud. 2017, 33, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, D.E.; Aloe, A.M. The prevalence of pathological gambling among college students: A meta-analytic synthesis, 2005–2013. J. Gambl. Stud. 2014, 30, 819–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.M.; Hong, S.; Kim, S.B.; Sohn, S. Examining risk and protective factors of problem gambling among college students in South Korea. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 105, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.M. Structural analysis on the path of problem gambling among college students: Using Jacob’s general theory of addiction. Korean J. Soc. Welf. 2013, 65, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Cho, M.J.; Jeon, H.J.; Lee, H.W.; Bae, J.N.; Park, J.I.; Sohn, J.H.; Lee, Y.R.; Lee, J.Y.; Hong, J.P. Prevalence, clinical correlations, comorbidities, and suicidal tendencies in pathological Korean gamblers: Results from the Korean Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 45, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehdonvirta, V.; Oksanen, A.; Räsänen, P.; Blank, G. Social media, web, and panel surveys: Using non-probability samples in social and policy research. Policy Internet 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, A.; Sirola, A.; Savolainen, I.; Kaakinen, M. Gambling patterns and associated risk and protective factors among Finnish young people. Nord. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2019, 36, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, P.G. Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 66, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, D.; Blaszczynski, A. Paid online convenience samples in gambling studies: Questionable data quality. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesieur, H.R.; Blume, S.B. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. Am. J. Psychiatry 1987, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby, T. Substance and Behavioral Addictions Assessment Instruments. In The Cambridge Handbook of Substance and Behavioral Addictions; Sussman, S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrén, S.; Kontto, J.; Alho, H.; Salonen, A.H. The relationship between gambling expenditure, socio-demographics, health-related correlates and gambling behaviour—A cross-sectional population-based survey in Finland. Addiction 2018, 113, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, A.H.; Alho, H.; Castrén, S. Attitudes towards gambling, gambling participation, and gambling-related harm: Cross-sectional Finnish population studies in 2011 and 2015. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodie, A.S.; MacKillop, J.; Miller, J.D.; Fortune, E.E.; Maples, J.; Lance, C.E.; Campbell, W.K. Evaluating the South Oaks Gambling Screen with DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria: Results from a diverse community sample of gamblers. Assessment 2013, 20, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenck, S.B.G.; Eysenck, H.J. Impulsiveness and Venturesomeness: Their Position in a Dimensional System of Personality Description. Psychol. Rep. 1978, 43, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, R.W.; Hendin, H.M.; Trzesniewski, K.H. Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NLSY79 Children & Young Adults. NLSY79 Child & Young Adults Data Users Guide; Center for Human Resource Research, The Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.nlsinfo.org/pub/usersvc/Child-Young-Adult/2006ChildYA-DataUsersGuide.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Harden, K.P.; Tucker-Drob, E.M. Individual differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity during adolescence: Further evidence for a dual systems model. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 47, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Harlow, L.L.; Puggioni, G.; Redding, C.A. A comparison of different methods of zero-inflated data analysis and an application in health surveys. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2017, 16, 518–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Regression Analysis of Count Data, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; p. 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, A.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Suler, J. Fostering empowerment in online support groups. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 1867–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.T.; Wood, S.A. An evaluation of two United Kingdom online support forums designed to help people with gambling issues. J. Gambl. Issues 2009, 23, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Castren, S.; Murto, A.; Salonen, A. Rahapelimarkkinointi yhä aggressiivisempaa–unohtuvatko hyvät periaatteet? Yhteiskuntapolitiikka 2014, 79, 438–443. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2014090444492 (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Littler, A.; Jarvinen-Tassopoulos, J. Online Gambling, Regulation, and Risks: A Comparison of Gambling Policies in Finland and the Netherlands. J. Law Soc. Policy 2018, 30, 100–126. Available online: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/jlsp/vol30/iss1/6 (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Hörnle, J.; Littler, A.; Tyson, G.; Padumadasa, E.; Schimidt-Kessen, M.J.; Ibosiola, D.I. Evaluation of Regulatory Tools for Enforcing Online Gambling Rules and Channelling Demand towards Controlled Offers; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6bac835f-2442-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Kuentzel, J.G.; Henderson, M.J.; Melville, C.L. The impact of social desirability biases on self-report among college student and problem gamblers. J. Gambl. Stud. 2008, 24, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Finland | United States | South Korea | Spain | All | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Scale | M/% | M/% | M/% | M/% | M/% |

| Problem gambling (SOGS) | 0–20 | 1.59 | 1.26 | 0.73 | 1.81 | 1.35 |

| ≥8 points | 3.67% | 3.63% | 1.76% | 6.27% | 3.84% | |

| Independent variables | ||||||

| Intrapersonal | Scale | M/% | M/% | M/% | M/% | M/% |

| Gender (male) | F/M | 50.00% | 49.83% | 49.58% | 51.24% | 50.17% |

| Age | 15–25 | 21.29 | 20.05 | 20.61 | 20.07 | 20.50 |

| Impulsivity | 0–5 | 1.96 | 1.90 | 1.56 | 2.05 | 1.87 |

| Self-esteem | 1–10 | 5.99 | 6.04 | 5.81 | 6.10 | 5.99 |

| Risk-taking | 1–10 | 5.12 | 5.74 | 4.21 | 5.41 | 5.12 |

| Interpersonal | Scale | M/% | M/% | M/% | M/% | M/% |

| Perceived social support (high) | low/high | 52.92% | 41.34% | 23.07% | 48.76% | 41.57% |

| Belonging offline | 1–10 | 6.73 | 6.78 | 6.69 | 7.11 | 6.83 |

| Belonging online | 1–10 | 5.04 | 5.38 | 4.38 | 4.91 | 4.93 |

| Social media identity bubble | 1–10 | 4.63 | 5.96 | 5.26 | 5.75 | 5.40 |

| Conformity to group norms | 0–4 | 1.27 | 1.66 | 1.67 | 1.79 | 1.60 |

| Organizational | Scale | % | % | % | % | % |

| Consumer debt | No/yes | 12.17% | 9.32% | 5.54% | 8.83% | 8.97% |

| Online casino participation | No/yes | 42.33% | 18.23% | 8.05% | 28.22% | 24.23% |

| Online gambling community participation | No/yes | 14.42% | 13.94% | 7.13% | 25.58% | 15.30% |

| Pop-up gambling advertisements | Never | 9.00% | 27.15% | 37.58% | 8.17% | 20.43% |

| Max monthly | 59.58% | 53.80% | 49.92% | 53.71% | 54.26% | |

| Weekly | 31.42% | 19.06% | 12.5% | 38.12% | 25.31% |

| Finland | United States | South Korea | Spain | All | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p |

| Male gender | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.05 | 0.060 | 0.18 | <0.001 | −0.06 | 0.073 | 0.15 | <0.001 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Impulsivity | 0.19 | <0.001 | 0.21 | <0.001 | 0.12 | <0.001 | 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Self-esteem | −0.15 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.383 | −0.07 | 0.012 | −0.05 | 0.097 | −0.06 | <0.001 |

| Risk-taking | 0.11 | 0.002 | 0.10 | <0.001 | 0.19 | <0.001 | 0.17 | <0.001 | 0.16 | <0.001 |

| Model adjusted R2 | 12% | 11% | 8% | 15% | 11% | |||||

| Interpersonal | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p |

| Perceived social support (high) | −0.08 | 0.012 | −0.16 | <0.001 | −0.04 | 0.193 | −0.20 | <0.001 | −0.09 | <0.001 |

| Belonging offline | −0.13 | 0.001 | −0.03 | 0.418 | −0.11 | <0.001 | −0.03 | 0.399 | −0.08 | <0.001 |

| Belonging online | 0.04 | 0.149 | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.13 | <0.001 | 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Social media identity bubble | 0.02 | 0.630 | 0.08 | 0.008 | 0.08 | 0.002 | 0.12 | <0.001 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Conformity to group norm | 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.10 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.002 | 0.06 | 0.014 | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| Model adjusted R2 | 5% | 6% | 4% | 11% | 5% | |||||

| Organizational | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p |

| Consumer debt | 0.19 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 00.067 | 0.18 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.004 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Online casino participation | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.002 | 0.12 | 0.175 | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| Online gambling community partic. | 0.25 | <0.001 | 0.26 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 0.001 | 0.26 | <0.001 | 0.28 | <0.001 |

| Pop-up gambling advertisements (ref. never) | ||||||||||

| Max monthly | −0.04 | 0.504 | 0.07 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.005 | 0.06 | 0.018 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Weekly | −0.03 | 0.650 | 0.17 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.18 | <0.001 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Model adjusted R2 | 22% | 23% | 29% | 26% | 26% | |||||

| Societal | β | p | ||||||||

| Country difference (ref. Spain) Finland | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.04 | 0.049 |

| United States | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.09 | 0.000 |

| South Korea | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.18 | 0.000 |

| Model adjusted R2 | 3% | |||||||||

| Finland | United States | South Korea | Spain | All | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p |

| Male gender | 0.12 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.08 | <0.001 | 0.13 | <0.001 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.06 | 0.015 | 0.10 | 0.001 | −0.08 | 0.009 | 0.06 | 0.026 | 0.01 | 0.398 |

| Impulsivity | 0.13 | <0.001 | 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.102 | 0.13 | <0.001 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Self-esteem | −0.06 | 0.027 | 0.01 | 0.867 | −0.06 | 0.028 | −0.03 | 0.289 | −0.03 | 0.048 |

| Risk-taking | 0.05 | 0.094 | 0.05 | 0.092 | 0.07 | 0.010 | 0.07 | 0.003 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Interpersonal | ||||||||||

| Perceived social support (high) | −0.03 | 0.206 | −0.06 | 0.053 | 0.02 | 0.490 | −0.09 | 0.003 | −0.06 | <0.001 |

| Belonging offline | −0.07 | 0.029 | −0.01 | 0.864 | −0.04 | 0.236 | −0.02 | 0.596 | −0.04 | 0.030 |

| Belonging online | −0.02 | 0.411 | 0.02 | 0.494 | 0.00 | 0.908 | 0.08 | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.033 |

| Social media identity bubble | 0.02 | 0.446 | 0.00 | 0.946 | 0.03 | 0.158 | 0.02 | 0.368 | 0.03 | 0.058 |

| Conformity to group norm | 0.06 | 0.037 | 0.04 | 0.089 | 0.06 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.435 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Organizational | ||||||||||

| Consumer debt | 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.352 | 0.18 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.034 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Online casino participation | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.011 | 0.11 | 0.214 | 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| Online gambling comm. partic. | 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 0.002 | 0.21 | <0.001 | 0.23 | <0.001 |

| Pop-up gambling advertisements (ref. never) | ||||||||||

| Max monthly | −0.02 | 0.739 | 0.04 | 0.045 | 0.03 | 0.106 | 0.04 | 0.205 | 0.02 | 0.073 |

| Weekly | −0.02 | 0.790 | 0.13 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.008 | 0.13 | <0.001 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Societal | ||||||||||

| Country difference (ref. Spain) Finland | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.01 | 0.446 |

| United States | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.03 | 0.056 |

| South Korea | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.05 | 0.004 |

| Model adjusted R2 | 28% | 27% | 31% | 33% | 31% | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oksanen, A.; Sirola, A.; Savolainen, I.; Koivula, A.; Kaakinen, M.; Vuorinen, I.; Zych, I.; Paek, H.-J. Social Ecological Model of Problem Gambling: A Cross-National Survey Study of Young People in the United States, South Korea, Spain, and Finland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063220

Oksanen A, Sirola A, Savolainen I, Koivula A, Kaakinen M, Vuorinen I, Zych I, Paek H-J. Social Ecological Model of Problem Gambling: A Cross-National Survey Study of Young People in the United States, South Korea, Spain, and Finland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063220

Chicago/Turabian StyleOksanen, Atte, Anu Sirola, Iina Savolainen, Aki Koivula, Markus Kaakinen, Ilkka Vuorinen, Izabela Zych, and Hye-Jin Paek. 2021. "Social Ecological Model of Problem Gambling: A Cross-National Survey Study of Young People in the United States, South Korea, Spain, and Finland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063220

APA StyleOksanen, A., Sirola, A., Savolainen, I., Koivula, A., Kaakinen, M., Vuorinen, I., Zych, I., & Paek, H.-J. (2021). Social Ecological Model of Problem Gambling: A Cross-National Survey Study of Young People in the United States, South Korea, Spain, and Finland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063220