Evaluation of the Dissemination of the South African 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Birth to 5 Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The feasibility of implementing the dissemination workshops;

- The acceptability of the dissemination workshops (and the guidelines) for different end-user groups; and

- The extent to which CBO representatives disseminated the guidelines to their staff and end-users.

2. Materials and Methods

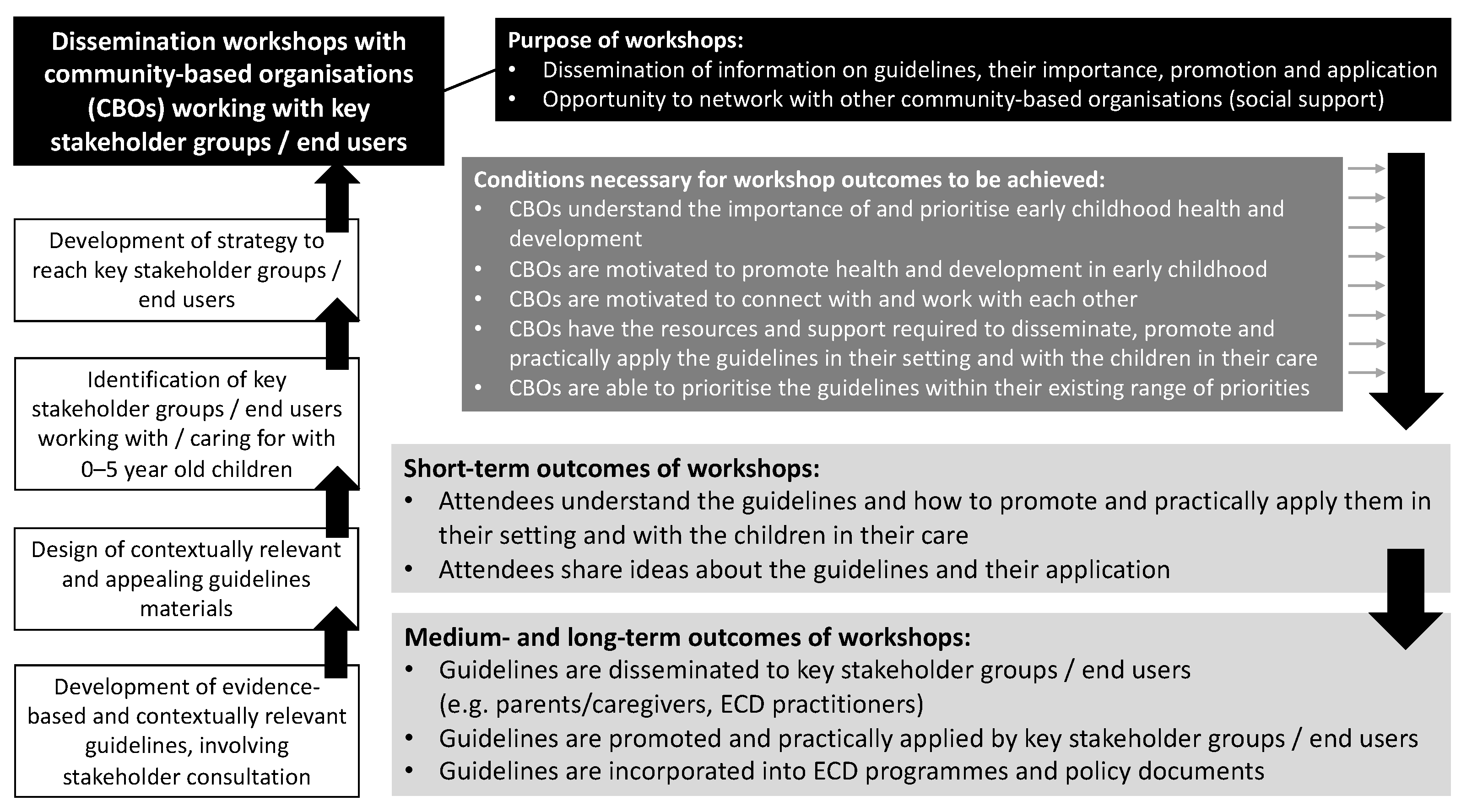

2.1. Programme Theory

2.2. Phase 1: Compilation of CBO Database and Dissemination Workshop Planning

2.3. Phase 2: Implementation and Evaluation of Dissemination Workshops

2.4. Phase 3: Marketing Campaign Development

2.5. Phase 4: Follow-Up Focus Groups

3. Results

3.1. Implementation of Dissemination Workshops

3.2. Quantitative Evaluation of Workshops

3.3. Qualitative Evaluation of the Workshops

3.3.1. Perceptions of the Workshops

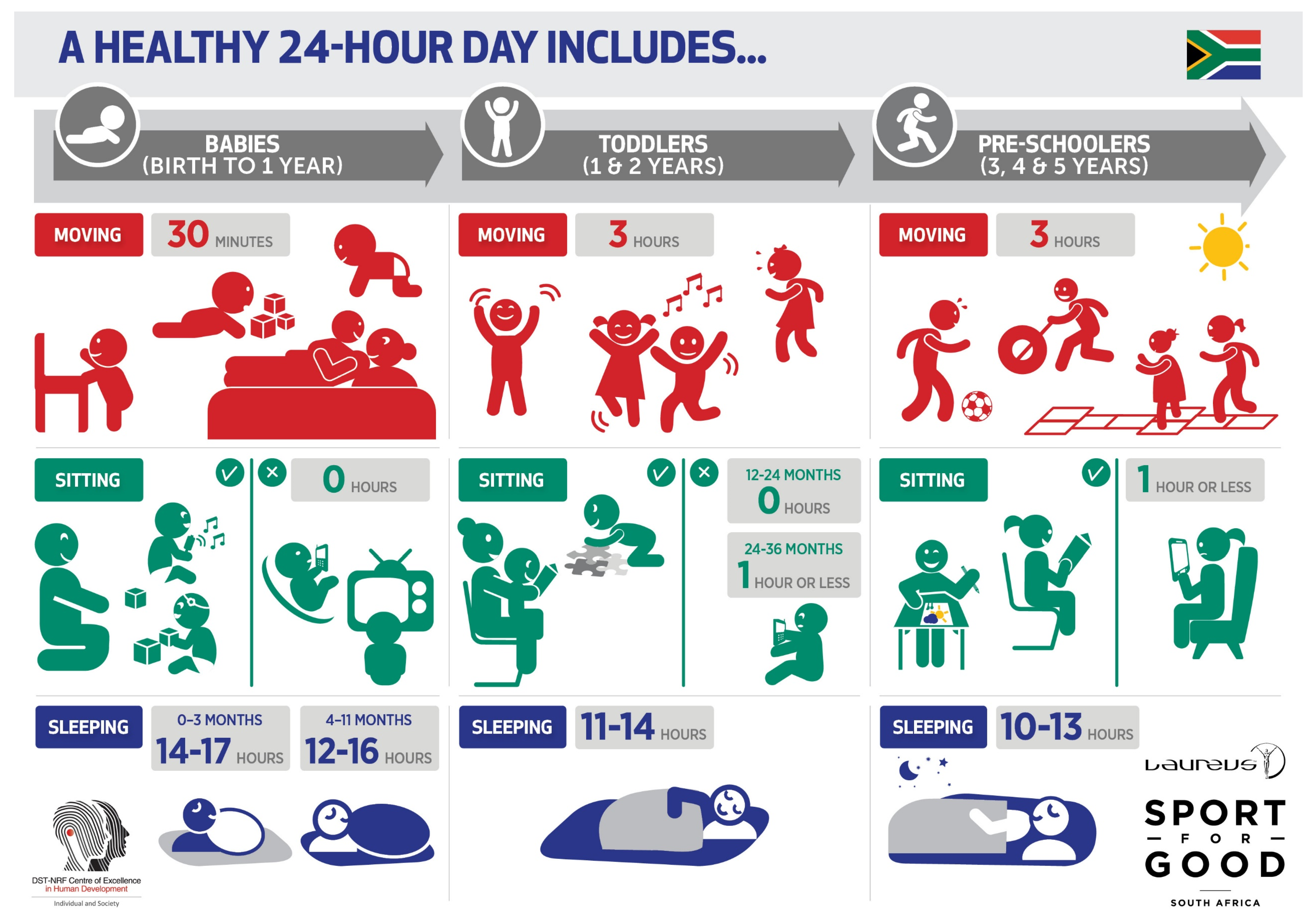

It showed us a lot on what they need and what is important and what not to do, and how to explain to the parents like what not to do. (Bloemfontein)This workshop helped me to understand a child who is aged from 0–1 years old, that from that age what a child is supposed to be doing and the activities that they should be taking part in. Then they move from 1–2 years old…I didn’t know that they mustn’t watch TV because when they don’t watch TV they have a higher concentration span. So it helped to get information like that and to even know how a child from 3–5 acts. (Giyani)Another thing that I’ve learned from the workshop we need to have a proper talk with our grandmothers because most of the time our children especially at the early age they are spending the time with their grandmothers especially while you are working. So, we need to share the information with them so they can know what is expected from them and what they are doing. It is going to affect the life of the child. I’m happy about this workshop. (Mbombela)I have learnt more because the training has helped me to see and learn a lot. I have seen and heard a lot of things like improvising, I cannot sit with children in our centre and say we don’t have money for toys. We can involve our parents to come to the centre and make these toys for our children with our own hands, home-made toys. (Polokwane)So from my side I think you know it helps me to understand that technology is not the only way to make the children learn and move, because sometimes you think that if we have those tablets we put or some children with TV on their desk they watch the TV the whole day, they are learning while they do a lot of activities. (Pretoria)

3.3.2. The Role of Parents

You mentioned that restricting children with screen time especially. If we set a good example of not being on our phones the whole day, or in front of the television all day. That example is what the child remembers as well, it’s up to us to set good example especially for screen time, in this day and age where everyone has a phone and everyone has a television on the whole day we actually set an example for that. (Pretoria)

3.3.3. Challenges to Implementation

So think one of the biggest…challenges of implementing something new is the idea of behaviour change and trying to influence that is quite difficult. In our setting it is sort of easy to revert back to that, oh we don’t have the time, we don’t have the space…I don’t have the money to be able to do this. (Cape Town)Unfortunately, everyone is busy these days. You go to the clinic and hospitals and they tell you that they are too busy for that. You go to a pre-school where they have a full class of kids and they don’t know what to do with them. So everyone is busy, the parents are busy, they wake up at 3 am to go to work, but the least they can do in dedicate a few minutes of their time to their child. (Johannesburg)

I think certainly with ECD practitioners and caregivers working with your children they sometimes feel like they have to limit what the children are doing because it is more about keeping them disciplined and safe and it is often for good reasons like safety and security and that sort of thing. (Cape Town)There is a lot of factors that influence this 24-h day…where we work, the number one factor is nutrition and I think that we need to factor that in when we think about the 24-h day. There are also a lot of social challenges, there is a lot of poverty and where there is poverty, the kids are not eating there is malnutrition. (Cape Town)

And funding and mentoring after the workshop, you can mentor us until you see the things happening and funding, funding is a key problem. (Sweetwaters)

3.3.4. Suggestions for the Workshops

Because we as the teachers would be giving them a brief workshop here but the problem is the parents and they always have the questions that need to be answered. So, my plea is not let it be a once-off thing. Yes, we hear it but when you get to the centre and stand in front of them there is some information that you forget about. So, please we hope to see you next time again. (Mbombela)

What I think what would be great to maybe even add to this because obviously you weren’t able to add all the details and some more extensive ideas. Like what we would do with those activities, what we would do in that programme is that we have a ball, the one day you let the children roll it, and the next day do something different with it. You will teach the caregivers something done in a different way and these are the 20 different things that you can do with it. And some more practical ideas like that might help and also in infographic form and even in this type of form as well. (Sweetwaters)

3.4. “Woza, Mntwana” Campaign

3.5. Follow-Up Focus Groups

3.5.1. Feedback on Workshops

I would say at first, they were like laughing…”what is happening with the screen?”…then until we explained to them that the screen is not good for the child, because the screen takes too much time of the child. And that is when they had to understand that okay, maybe that is why some of the things…At first, we didn’t know…So if you explain it better to the parents, then the parents tend to understand. (Gauteng, peri-urban 1)I think screen time affects the entire daily routine because as I have been saying the children watch TV till late and this affects them in preschool the next day so I am really keen to give this information to the teachers so they can relay it to the parents. (KZN 1)The workshop really helped us in terms of strengthening our knowledge, especially around physical movement because we were looking at the milestones of the children. So, it would help us to educate our parents and our caregivers, especially around physical activity for the child around, movement, around sleep and around screen time…So, it really helped us from a parenting perspective so that we can empower our caregivers or our beneficiaries that they can also do those activities during the day with their children as well. (Gauteng, peri-urban 1)We’d like to just sincerely thank you for the knowledge that you gave us, and it has been helpful for us in through our work and with the clients that we are working with, and building as well the relationship between the mother and us, so that they trust us more with their children, and they trust us more that we’re going to help them in so many ways; not just…in a health related way, but also in a way of bonding with their children and learning the child’s stimulation and the milestone for their children. So, we really appreciate that. (Gauteng, peri-urban 1)

3.5.2. Extent of Dissemination to CBO Staff and End-Users

When it had just came out I think it was through (ECD network name), we heard about it and we were so excited. And we did a…training morning about it and it was quite interesting for us to us to see the numbers and we played a little bit of a guessing games on “how much do you think they can sit?” And it was very interesting for the team to see what it was, so we were already enthusiastic about it, and then we managed to attend that meeting…that was also helpful. And then what we did with it was that, in the homes we already have a curriculum where we do different things every week so movement has always been part of what we did but we could add more from of your ideas, and we could change one whole lesson from our curriculum so it could be based around the movement guideline. During that lesson we were able to hand out the pamphlets and things so there was that extra focus and then we could remind them that when we talk about TV time or sitting time then it would link back to these movement guidelines. (KZN)

We shared with the team at the office, to say these are the guidelines and then with the side teams because they took the resources and they were able to incorporate it in their health education, in their play sessions…We took the hard copies and the nice things that we took there were in different languages. So if we were having a session with a Zulu speaking client, then we were able to share those hard copies as well…we also share with the health professional team that we work with in the facilities, so that they also understand what we are doing, they mustn’t be surprised that now we are doing this to the children. We show them that these are the guidelines from the workshop that we attended and these are what the recommendations are. (Gauteng, peri-urban 1)We took from you and we made copies for all our centres, we gave it to them, laminated them for them and they put them up in the classrooms so that the teachers can be reminded that this is what they need to follow and what they can instil in the classes and the children. (Cape Town)Fortunately, we do trainings every Fridays, so as soon as we received the, the whole memo we kind of integrated it with mental health also around children…we took the whole pamphlet and broke it down to trainings also on mental health around children, also on reporting incidents, and also on like developmental milestones for children. (Gauteng, urban)After the training, we went to the facility managers…that’s where we shared the guidelines with them and they were so excited for the guideline…some of the posters, they took it and they paste it in each and every room where mother and child has been feeding, or where a mother comes in, can be able to identify and maybe be able to stimulate the child…They were actually excited and happy for us to bring those guidelines to them. (Gauteng, peri-urban 2)

Remember we have that tendency that in order for the child to play, we have to go to the shops and buy the toys. So what we did, we had to go back to them and show them other, I would say other skills to make toys for the child. We don’t have to go and buy because remember not all of us are working. Not all of us are getting enough money to buy the toys, so we have to teach them how to make toys, and then we have to teach them how to play with the children. (Gauteng, peri-urban 1)

3.5.3. Responses of CBO Staff and End-Users

Because the biggest questions were coming from parents…let’s say for instance you say no screen time, they’re asking then what must I do? What can I substitute the screen time with? Or what can I do with the child or what can the child do in the meantime, just so they don’t cry? Because then it’s not fair for you to take away the TV without introducing something else. (Gauteng, urban)The professionals…after sharing with them those things, I would say the response was good, especially the PMTC (prevention of mother to child transmission) staff. Because they are the ones who are helping us with the children and all that. It also gave them…I would say a wake-up call on how relaxed we are with our children at home. (Gauteng, peri-urban 1)The babies were not moving that much because…the parents would just put them in bed and not do anything with them throughout the day. So, we actually told them that they can move with the babies, do some activities, play with the babies and let them sit, not allow them to watch TV or any screens. And it was actually so great for them because they did not know what to do and we got some really good feedback from them was really good because they could see some changes as time went on. (KZN 1)After they tried implementing what we taught them they started seeing results, like kids remembering things they had learned from outside of TV more than what they learned on TV. So I think they were quite happy with the information. (KZN 1)

Most of the women are very young, they’re not able to talk to the children maybe to play with the children; they’re used to making them watch TV… In our district we have a lot of teenage pregnancy…They have to go back to school, so the grannies have to look after the child. So, we also teach the grannies how to look after the child when the mother is at school. (KZN 2)People who were listening more to these more were more the grandparents who were there; I mean older ladies they will understand this information better than the younger ones. (Gauteng, urban)

3.5.4. Perceptions of “Woza, Mntwana” Song and Recommendations for Dissemination

I can hear it playing on a radio, it is and it’s quite catchy with the chorus you know. I think I like the fact that there’s, what four, four five different languages. (Cape Town)Very beautiful indeed. (Gauteng, urban)I love the rhythm…And I love the message as well, and the fact that uh we’ll be able to be singing and playing uh along with the babies…It encourage the mother to… say to the child come closer baby, come closer…it’s a good sing along…I think if the mother can sing and dance with the child…even now the babies were concentrating on the song… Here is the baby singing (laughs)…Can you hear the baby singing? (Gauteng, peri-urban 2)

So that’s where you can play with your child while listening to the song, and then you can… the baby can even fall asleep, you can sing it to the baby… yes and it helps uh, uh I think it will help a mother and a child to bond…It is the perfect song; you can sing along with the baby or play it when bathing the baby. (Gauteng, peri-urban 2)The song is useful to our children especially in vocabulary, the children uh when they are singing they are developing their language…And another thing, they, they will be singing in a group; so when singing in a group they’ll, they’ll socialise with other children…so for me this song is very useful especially for our children. (Gauteng, peri-urban 1)I would use the song in the morning as a morning ring just before the activities and maybe add a few dance moves so we can be active. (KZN 1)

They (children) would probably sing it, but it would be nice to have something that you could put actions to as well, which you could, that you could also do more. (Cape Town)I think for them to sing it with me first would be really nice so they know how to dance to it so they know how to use it otherwise it’s pointless to give them something they don’t know how to use you know, I mean it’s a very simple song so there shouldn’t be anything complicated about it. (KZN 1)

In our play group, so they usually… one would be bringing their own… oh, I know all of them actually brought their Bluetooth speakers and then whatever song they needed to do uh I would just help them download it and then circulate it on our WhatsApp group and that’s how they would get it. (Gauteng, urban)I also think if you want it, it becomes like, for practitioners, like a nursery rhyme, they do it every day with the kids, the kids go out, go home and sing it all the way, so the same with the song, if they teach the children in class, they will go home and parents will listen to what they singing. (Cape Town)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tremblay, M.S.; Chaput, J.-P.; Adamo, K.B.; Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Choquette, L.; Duggan, M.; Faulkner, G.; Goldfield, G.S.; Gray, C.E.; et al. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the Early Years (0–4 years): An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep, 2nd ed.; BMC Public Health: London, UK, 2017; Volume 17, pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Okely, A.D.; Ghersi, D.; Hesketh, K.D.; Santos, R.; Loughran, S.P.; Cliff, D.P.; Shilton, T.; Grant, D.; Jones, R.A.; Stanley, R.M.; et al. A Collaborative Approach to Adopting/Adapting Guidelines—The Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the Early Years (Birth to 5 Years): An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Sleep, 2nd ed.; BMC Public Health: London, UK, 2017; Volume 17, p. 869. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, J.J.; Hughes, A.R.; Janssen, X.; Hesketh, K.; Livingstone, S.; Hill, C.; Kipping, R.; Draper, C.E.; Okely, A.D.; Martin, A. GRADE ADOLOPMENT Process to Develop 24-Hour Movement Behavior Recommendations and Physical Activity Guidelines for the Under 5s in the UK, 2019. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Sit Less, Move More, Sleep Well: Active Play Guidelines for Under-Fives; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2017; pp. 1–34.

- Willumsen, J.; Bull, F. Development of WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Sleep for Children Less Than 5 Years of Age. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper, C.E.; Tomaz, S.A.; Biersteker, L.; Cook, C.J.; Couper, J.; de Milander, M.; Flynn, K.; Giese, S.; Krog, S.; Lambert, E.V.; et al. The South African 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Birth to 5 Years: An Integration of Physical Activity, Sitting Behavior, Screen Time, and Sleep. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaz, S.A.; Okely, A.D.; van Heerden, A.; Vilakazi, K.; Samuels, M.-L.; Draper, C.E. The South African 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Birth to 5 Years: Results From the Stakeholder Consultation. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinembiri, T. Despite Reduction in Mobile Data Tariffs, Data still Expensive in South Africa; Research ICT Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Blignaut, P.; Fuchs, C.; Horak, E. Levels of Digital Divide in South Africa; SANGONeT: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2020; Available online: http://www.ngopulse.org/article/2020/08/28/levels-digital-divide-south-africa (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Department of Trade, Industry and Competition. Recommended Guidelines—Fabric Face Masks; Department of Trade, Industry and Competition: Pretoria, South Africa, 2020; pp. 1–16.

- Vorster, H.H.; Badham, J.B.; Venter, C.S. An introduction to the revised food-based dietary guidelines for South Africa. South Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 26, S5–S12. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, I.; Lang, T. Food-based dietary guidelines and implementation: Lessons from four countries—Chile, Germany, New Zealand and South Africa. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper, C.E.; Howard, S.J.; Rochat, T.J. Feasibility and acceptability of a home-based intervention to promote nurturing interactions and healthy behaviours in early childhood: The Amagugu Asakhula pilot study. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingberg, S.; van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Jong, S.; Draper, C.E. Can public sector community health workers deliver a nurturing care intervention in South Africa? A qualitative process evaluation of Amagugu Asakhula. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasone, J.R.; Kauffeldt, K.D.; Morgan, T.L.; Magor, K.W.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Faulkner, G.; Ross-White, A.; Poitras, V.; Kho, M.E.; Ross, R. Dissemination and implementation of national physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and/or sleep guidelines among community-dwelling adults aged 18 years and older: A systematic scoping review and suggestions for future reporting and research. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45 (Suppl. 2), S258–S283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, P.R.; Lye, S.J.; Proulx, K.; Yousafzai, A.K.; Matthews, S.G.; Vaivada, T.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Rao, N.; Ip, P.; Fernald, L.C.; et al. Nurturing care: Promoting early childhood development. Lancet 2017, 389, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Pell, C.; Cheah, P.Y. Community engagement and ethical global health research. Glob. Bioeth. 2020, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 10 min | Arrivals and refreshments Provide name tags |

| 5 min | Welcome and introductions |

| 45 min | Presentation of guidelines Question time |

| 30 min | Case studies (depending on time) |

| 20 min | Verbal feedback from the group (group discussion) |

| 10 min | Written feedback (evaluation form) |

| (120 min) | Workshop end |

| Workshop | Location | Attendees | Attendees (n) | Evaluation Forms (n, % Response) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cape Town, Western Cape Province (urban) | CBO representatives, local government representatives, ECD practitioners, academics, students | 30 | 30 (100%) |

| 2 | Cape Town, Western Cape Province (urban) | CBO representatives | 11 | 8 (72.7%) |

| 3 | Durban, KwaZulu-Natal Province (urban) | CBO representatives | 9 | 9 (100%) |

| 4 | Sweetwaters, KwaZulu-Natal Province (rural) | CBO representatives, community college representative | 5 | 5 (100%) |

| 5 | Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape Province (urban) | ECD practitioners, biokineticist (exercise therapist), student biokineticist | 8 | 5 (6.3%) |

| 6 | Johannesburg, Gauteng Province (urban) | CBO representatives, community stakeholders | - * | - * |

| 7 | Johannesburg, Gauteng Province (urban) | CBO representatives, ECD practitioners | 13 | 7 (53.8%) |

| 8 | Pretoria, Gauteng Province (urban) | CBO representatives, academics, students, ECD practitioners | 101 | 78 (77.2%) |

| 9 | Polokwane, Limpopo Province (urban—small city) | CBO representatives | 21 | 19 (90.5%) |

| 10 | Giyani, Limpopo Province (rural) | ECD practitioners | 20 | 20 (100%) |

| 11 | Giyani, Limpopo Province (rural) | ECD practitioners | 28 | 28 (100%) |

| 12 | Mbombela, Mpumalanga (urban—small city) | CBO representatives | 7 | 2 (28.6) |

| 13 | Mbombela, Mpumalanga (urban—small city) | Provincial government representatives | 14 | 14 (100%) |

| 14 | Bloemfontein, Free State Province (urban) | Academics, students | 14 | 14 (100%) |

| 15 | Worcester, Western Cape Province (rural) | ECD practitioners | 42 | 42 (100%) |

| Total | 323 | 281 (87%) |

| Workshop Evaluation Questions (n = 281) | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The workshop helped me to understand 24-h movement behaviours | 54.8% | 41.3% | 3.2% | 0% | 0.7% |

| The workshop helped me to understand how to share the guidelines with others | 51.2% | 44.8% | 3.2% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| The workshop helped me to see the importance of healthy movement behaviours in young children | 55.9% | 40.2% | 3.2% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| I think that these guidelines are needed in South Africa | 64.8% | 33.1% | 2.1% | 0% | 0% |

| I have the resources I need to promote the guidelines with the people I work with | 37.7% | 46.6% | 13.2% | 1.8% | 0.7% |

| I have the support I need to promote the guidelines with the people I work with | 38.4% | 49.1% | 11.4% | 1.1% | 0% |

| I feel confident that I can share these guidelines with the people I work with | 54.8% | 41.6% | 3.2% | 0.4% | 0% |

| I would recommend this workshop to others who work with carers of children from birth to five years | 60.5% | 37.0% | 1.1% | 0.7% | 0.7% |

| Open-ended responses to “Do you have any other feedback about the workshop on the guidelines?” | |||||

| “Discussion at the end was good. it is good for practitioners to discuss issues.” “Well-presented and clearly articulated as well as easy to follow and most importantly implement.” “Infographic was easy to understand.” “The importance of a routine according to age was novel.” “A very good workshop, sleep time was a revelation.” “I have gained a lot of knowledge. I was given ideas on how to implement these guidelines.” “I have gained a lot of knowledge and I will share with communities.” “I have been equipped with knowledge that I can pass on to parents.” “Parent workshops are needed.” “Practical examples needed, training of new parents and new teachers.” “Annual workshop would be beneficial.” “This is only the beginning; behavioural change is needed. Behavioural change needs multifaceted support.” “Media needs to be used to disseminate information. Parents need to be educated.” | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Draper, C.E.; Silubonde, T.M.; Mukoma, G.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Evaluation of the Dissemination of the South African 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Birth to 5 Years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063071

Draper CE, Silubonde TM, Mukoma G, van Sluijs EMF. Evaluation of the Dissemination of the South African 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Birth to 5 Years. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063071

Chicago/Turabian StyleDraper, Catherine E., Takana M. Silubonde, Gudani Mukoma, and Esther M. F. van Sluijs. 2021. "Evaluation of the Dissemination of the South African 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Birth to 5 Years" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 3071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063071

APA StyleDraper, C. E., Silubonde, T. M., Mukoma, G., & van Sluijs, E. M. F. (2021). Evaluation of the Dissemination of the South African 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Birth to 5 Years. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3071. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063071