Tools and Methods to Include Health in Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies and Policies: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

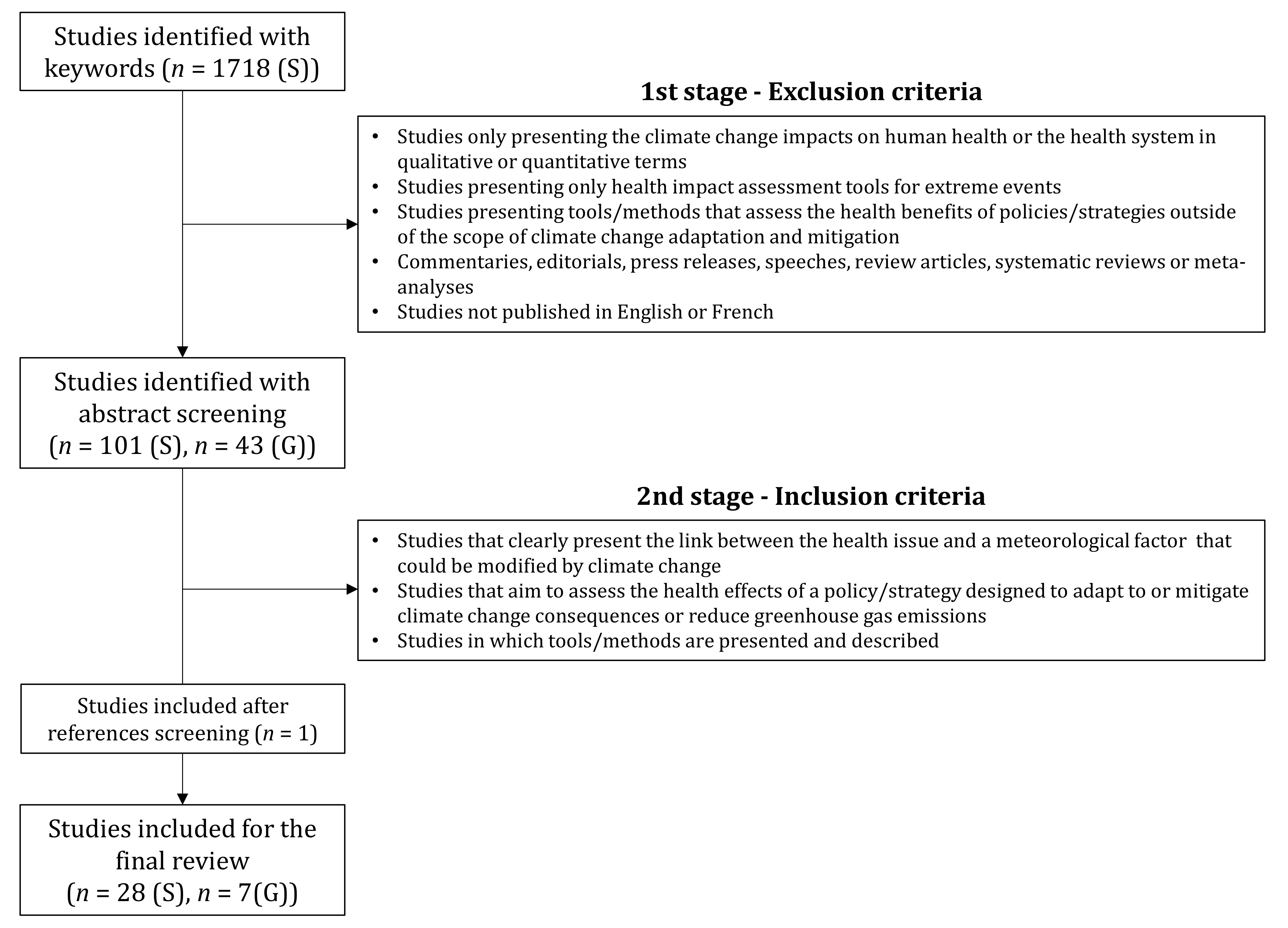

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Criteria

2.2. Selection Criteria

- Studies only presenting the climate change impacts on human health or the health system in qualitative or quantitative terms.

- Studies presenting only health impact assessment tools for extreme events (e.g., droughts, heatwaves, hurricanes).

- Studies presenting tools/methods that assess the health benefits of policies/strategies outside of the scope of climate change adaptation and mitigation.

- Commentaries, editorials, press releases, speeches, review articles, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses.

- Studies not published in English or French.

- Studies that clearly present the link between the health issue and a meteorological factor that could be modified by climate change.

- Studies that aim to assess the health effects of a policy/strategy designed to adapt to or mitigate climate change consequences or reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

- Studies in which tools/methods are presented and described.

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Description of Studies Selected

3.1.1. Scientific Literature

3.1.2. Grey Literature

3.2. Description of Tools Selected

3.2.1. Impact Assessment Tools

Health Impact Assessment (HIA)

Comparative Risk Assessment (CRA)

Integrated Environmental Health Impact Assessment (IEHIA)

Environmental Assessments

3.2.2. Adaptation tools

Vulnerability and Adaptation (V&A) Assessment

Health National Adaptation Process (HNAP)

- Step 1. Aligning the health adaptation planning process with the national process for developing a NAP;

- Step 2. Taking stock of available information;

- Step 3. Identifying approaches to address capacity gaps and weaknesses in HNAP implementation.

- Step 4. Conducting a V&A assessment in the health sector, including short- and long-term needs in the context of development priorities;

- Step 5. Examining the implications of climate change for development goals, legislation, strategies, policies, and plans related to health;

- Step 6. Developing a national health adaptation strategy that identifies priority adaptation options.

- Step 7. Elaborating an implementation strategy for operationalizing HNAPs and incorporating climate change adaptation in health-related planning processes at all levels, including strengthening the capacity for conducting future HNAPs;

- Step 8. Promoting coordination and synergies with the NAP process, especially with sectors affecting health, and with multilateral environmental agreements.

- Step 9. Following-up and reviewing the HNAP to assess progress, effectiveness, and gaps;

- Step 10. Updating the health component of the NAPs in an iterative manner;

- Step 11. Communicating and reporting on the progress and effectiveness of the HNAP implementation [45].

Economic Assessment Tool—Health and Adaptation Costs

3.2.3. Nested Models

3.2.4. Conceptual Frameworks

3.2.5. Other Methodological Approaches

Participatory approach

Mixed Methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; et al. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuor, L.; Meldrum, R.; Liberda, E.N. Institutional Engagement Practices as Barriers to Public Health Capacity in Climate Change Policy Discourse: Lessons from the Canadian Province of Ontario. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbhahn, N.; Fears, R.; Haines, A.; Ter Meulen, V. Urgent action is needed to protect human health from the increasing effects of climate change. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e333–e335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patz, J.A.; Frumkin, H.; Holloway, T.; Vimont, D.J.; Haines, A. Climate Change: Challenges and opportunities for global health. JAMA 2014, 312, 1565–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M. Achieving a cleaner, more sustainable, and healthier future. Lancet 2015, 386, e27–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.; Smith, B.A.; Fazil, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of extreme weather events and other weather-related variables on Cryptosporidium and Giardia in fresh surface waters. J. Water Health 2015, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, A. Health co-benefits of climate action. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e4–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jacob, D.; Taylor, M.; Bolaños, T.G.; Bindi, M.; Brown, S.; Camilloni, I.A.; Diedhiou, A.; Djalante, R.; Ebi, K.; et al. The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 °C. Science 2019, 365, eaaw6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maibach, E.W.; Sarfaty, M.; Mitchell, M.; Gould, R. Limiting global warming to 1.5 to 2.0 °C—A unique and necessary role for health professionals. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dannenberg, A.L.; Rogerson, B.; Rudolph, L. Optimizing the health benefits of climate change policies using health impact assessment. J. Public Health Policy 2020, 41, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, D.W.; Holloway, T.; Harkey, M.; Meier, P.; Ahl, D.; Limaye, V.S.; Patz, J.A. Air-quality-related health impacts from climate change and from adaptation of cooling demand for buildings in the eastern United States: An interdisciplinary modeling study. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, M.; Gosselin, P. An effective public health program to reduce urban heat islands in Québec, Canada. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2016, 40, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Briggs, D.J. A framework for integrated environmental health impact assessment of systemic risks. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 2008, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, J.J.; Luckow, P.; Fisher, J.; Kempton, W.; Levy, J. Health and climate benefits of offshore wind facilities in the Mid-Atlantic United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Hui, J.; Wang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Gong, P. The Lancet Countdown on PM 2·5 pollution-related health impacts of China’s projected carbon dioxide mitigation in the electric power generation sector under the Paris Agreement: A modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e151–e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Thatcher, M.; Barnett, G.; Kachenko, A.; Prince, R. Urban vegetation for reducing heat related mortality. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 192, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabai, A.; Quiroga, S.; Martinez-Juarez, P.; Higgins, S.; Taylor, T. The nexus between climate change, ecosystem services and human health: Towards a conceptual framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, T.; Cantoreggi, N.; Simos, J. Co-bénéfices pour la santé des politiques urbaines relatives au changement climatique à l’échelon local: L’exemple de Genève. Environ. Risques Sante 2016, 15, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, T.; Cantoreggi, N.; Simos, J.; Christie, D.P.T.H. Is HIA the most effective tool to assess the impact on health of climate change mitigation policies at the local level? A case study in Geneva, Switzerland. Glob. Health Promot. 2017, 24, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Menendez, F.; Saari, R.K.; Monier, E.; Selin, N.E. U.S. Air Quality and Health Benefits from Avoided Climate Change under Greenhouse Gas Mitigation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 7580–7588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haluza, D.; Kaiser, A.; Moshammer, H.; Flandorfer, C.; Kundi, M.; Neuberger, M. Estimated health impact of a shift from light fuel to residential wood-burning in Upper Austria. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, A.; Prudent, N.; Scott, J.E.; Wade, R.; Luber, G. Climate change-related vulnerabilities and local environmental public health tracking through GEMSS: A web-based visualization tool. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 33, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, A. Health Impact Assessments A Tool for Designing Climate Change Resilience Into Green Building and Planning Projects. J. Green Build. 2011, 6, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, S.C.; Tainio, M.; Woodcock, J.; Hashim, J.H. Health co-benefits in mortality avoidance from implementation of the mass rapid transit (MRT) system in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Rev. Environ. Health 2016, 31, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Crawford-Brown, D.J. Assessing the co-benefits of greenhouse gas reduction: Health benefits of particulate matter related inspection and maintenance programs in Bangkok, Thailand. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 1774–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, G.; Macmillan, A.; Woodward, A. Moving urban trips from cars to bicycles: Impact on health and emissions. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2011, 35, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markandya, A.; Armstrong, B.G.; Hales, S.; Chiabai, A.; Criqui, P.; Mima, S.; Tonne, C.; Wilkinson, P. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: Low-carbon electricity generation. Lancet 2009, 374, 2006–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, L.; Trüeb, S.; Cowie, H.; Keuken, M.P.; Mudu, P.; Ragettli, M.S.; Sarigiannis, D.A.; Tobollik, M.; Tuomisto, J.; Vienneau, D.; et al. Transport-related measures to mitigate climate change in Basel, Switzerland: A health-effectiveness comparison study. Environ. Int. 2015, 85, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarigiannis, D.A.; Kontoroupis, P.; Nikolaki, S.; Gotti, A.; Chapizanis, D.; Karakitsios, S. Benefits on public health from transport-related greenhouse gas mitigation policies in Southeastern European cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 1427–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.R.; Haigler, E. Co-Benefits of Climate Mitigation and Health Protection in Energy Systems: Scoping Methods. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.A.; Ruthman, T.; Sparling, E.; Auld, H.; Comer, N.; Young, I.; Lammerding, A.M.; Fazil, A. A risk modeling framework to evaluate the impacts of climate change and adaptation on food and water safety. Food Res. Int. 2015, 68, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.M.; Rausch, S.; Saari, R.K.; Selin, N.E. Air quality co-benefits of subnational carbon policies. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2016, 66, 988–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobollik, M.; Keuken, M.; Sabel, C.; Cowie, H.; Tuomisto, J.; Sarigiannis, D.; Künzli, N.; Perez, L.; Mudu, P. Health impact assessment of transport policies in Rotterdam: Decrease of total traffic and increase of electric car use. Environ. Res. 2016, 146, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuomisto, J.T.; Niittynen, M.; Pärjälä, E.; Asikainen, A.; Perez, L.; Trüeb, S.; Jantunen, M.; Künzli, N.; Sabel, C.E. Building-related health impacts in European and Chinese cities: A scalable assessment method. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 2015, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Williams, M.L.; Lott, M.C.; Kitwiroon, N.; Dajnak, D.; Walton, H.; Holland, M.; Pye, S.; Fecht, D.; Toledano, M.B.; Beevers, S.D. The Lancet Countdown on health benefits from the UK Climate Change Act: A modelling study for Great Britain. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e202–e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkinger, B.; Haas, W.; Bachner, G.; Weisz, U.; Steininger, K.; Hutter, H.P.; Delcour, J.; Griebler, R.; Mittelbach, B.; Maier, P.; et al. Evaluating Health Co-Benefits of Climate Change Mitigation in Urban Mobility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodcock, J.; Edwards, P.; Tonne, C.; Armstrong, B.G.; Ashiru, O.; Banister, D.; Franco, O.H.; Haines, A.; Hickman, R.; Lindsay, G.; et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: Urban land transport. Lancet 2010, 374, 1930–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Worrell, E.; Crijns-Graus, W.; Krol, M.; de Bruine, M.; Geng, G.; Wagner, F.; Cofala, J. Modeling energy efficiency to improve air quality and health effects of China’s cement industry. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 574–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, L.; Harrison, C.; Buckley, L.; North, S. Climate Change, Health, and Equity: A Guide for Local Health Departments; Public Health Institute: Oakland, CA, USA; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Human Health. In CGE Training Materials for Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2011; Chapter 8. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO); Regional Office for Europe [ROE]. Climate Change and Health: A Tool to Estimate Health and Adaptation Costs; WHO-ROE: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Methods of Assessing Human Health Vulnerability and Public Health Adaptation to Climate Change; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Protecting Health from Climate Change: Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Guidance to Protect Health from Climate Change through Health Adaptation Planning; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ebi, K.; Anderson, V.; Berry, P.; Paterson, J.; Yusa, A.; Gough, W.; Herod, K. Ontario Climate Change and Health Toolkit; Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Public Health Policy and Programs Branch: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4606-7703-2.

- World Health Organization. Health in the Green Economy: Health Co-Benefits of Climate Change Mitigation—Transport Sector; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati, M.; Van der Hoorn, S.; Rodgers, A.; Lopez, A.D.; Mathers, C.D.; Murray, C.J.; Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Estimates of global and regional potentil health gains from reducing muliple major risk factors. Lancet 2003, 362, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Woodruff, R. Comparative Risk Assessment of the Burden of Disease from Climate Change. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 1935–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, P.; Enright, P.M.; Shumake-Guillemot, J.; Prats, E.V.; Campbell-Lendrum, D. Assessing Health Vulnerabilities and Adaptation to Climate Change: A Review of International Progress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, T.; Delgado, M.; Greenstone, M.; Houser, T.; Hsiang, S.; Hultgren, A.; Jina, A.; Kopp, R.E.; McCusker, K.; Nath, I.; et al. Valuing the Global Mortality Consequences of Climate Change Accounting for Adaptation Costs and Benefits (No. w27599); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Jiang, C.; Murtugudde, R.; Liang, X.-Z.; Sapkota, A. Global Population Exposed to Extreme Events in the 150 Most Populated Cities of the World: Implications for Public Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemm, J. Chapter—Quantitative assessment. In Health Impact Assessment—Past Achievement, Current Understanding, and Future Progress; Kemm, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Veerman, J.; Barendregt, J.; MacKenbach, J.P. Quantitative health impact assessment: Current practice and future directions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.M.; Forster, H.I.; Evans, M.J.; Gidden, M.J.; Jones, C.D.; Keller, C.A.; LambolliD, R.D.; Le Quéré, C.; Rogelj, J.; Rosen, D.; et al. Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ciais, P.; Deng, Z.; Lei, R.; Davis, S.J.; Feng, S.; Zheng, B.; Cui, D.; Dou, X.; Zhu, B.; et al. Near-real-time monitoring of global CO2 emissions reveals the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ching, J.; Kajino, M. Rethinking Air Quality and Climate Change after COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, M.; Huang, C.; Kinney, P.L.; Anastas, P.T. Air pollution reduction and mortality benefit during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e210–e212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brient, F. Reducing Uncertainties in Climate Projections with Emergent Constraints: Concepts, Examples and Prospects. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Literature- | Source | Number of Documents | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific literature | Web of science | 575 | 1718 * |

| Pubmed | 525 | ||

| Embase | 982 | ||

| Grey literature | WHO | 19 | 43 |

| IPCC | 3 | ||

| WMO | 5 | ||

| Ministry of Environment | British Columbia (1); United States (3); California (1) | ||

| Ministry of Health | Ontario (2); British Columbia (1); Canada (1); California (1); France (1) | ||

| Others | 5 |

| (a) | ||||||||||||

| Author | Year | Climatic Event | Exposure | Health Issue | Strategy (Adaptation/Mitigation) | Tool Type | Name | Provider | Tool’s Objective | Scale of Application | Area | Measure of the Health Effect |

| Abel et al. [12] | 2018 | Rising temperatures | Air pollution (PM2.5 and ozone) | Incidence of premature mortality and morbidity | Mitigation | Nested models | EPA’s BenMAP Community Edition version 1.3 | US EPA | BenMAP calculates adverse health outcomes of air quality changes linked with adaptation in building energy use | Region | East and Midwest USA | Yes |

| Beaudoin et Gosselin [13] | 2016 | Rising temperatures | Urban heat islands | Well-being | Adaptation | Other methodological approach | UNSP | National Institute of Public Health of Québec | Assess the effects of Urban Heat Island on well-being and quality of life of residents and users. 4 criteria assessed: beauty, comfort, coolness, and security | City | Montréal (Canada) | No |

| Briggs [14] | 2008 | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP | Impact assessment tool | Integrated environmental health impact assessment | Imperial College London | Assess health-related issues deriving from the environment, and health-related impacts of policies and other interventions that affect the environment, taking into account complexities, interdependencies and uncertainties of the real world | Different scales (local to global) | UNSP | Yes |

| Buonocore et al. [15] | 2016 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5, NOx and SO2) | Premature deaths | Mitigation | Nested models | UNSP | Harvard University | Assess reductions in NOx, PM2,5 and CO2 and health gains associated (Premature deaths avoided per year) with offshore wind electricity | States | New Jersey and Maryland (USA) | Yes |

| Cai et al. [16] | 2018 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5) | Premature deaths | Mitigation | Nested models | UNSP | Joint Center for Global Change Studies | Assess reductions in NOx, PM2,5 and CO2 and associated health gains of carbon dioxide mitigation in the electric power generation sector | Country (subregions) | China | Yes |

| Chen et al. [17] | 2014 | Heatwaves | Air temperature | Heat-related mortality | Mitigation | Nested models | UNSP | CSIRO | Assess the impact of urban vegetation in the reduction of heat related mortality rate | City | Melbourne (Australia) | Yes |

| Chiabai et al. [18] | 2018 | Heatwaves, floods and heavy rainfalls | Urban heat islands, floods and air pollution (3 classes) | Multiples (non-specific) | UNSP | Conceptual framework | “Ecosystems enriched” Driver, Pressure, State, Exposure, Effect, Action (eDPSEEA) | BC3-Basque Centre for Climate Change, Spain | Linking CC impacts and adaptation actions on environment and assess how these actions could affect human health through various ways of exposure | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP |

| Diallo et al. [19] | 2016 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM10, NOx), noise | Disability adjusted life years (DALY) of sleep disorders and annoyance | Mitigation | Impact assessment tool | Health Impact Assessment | WHO | Assess the effects on health and well-being of greenhouse gases (GHG) reduction measures | City | Geneva (Switzerland) | Yes |

| Diallo et al. [20] | 2017 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM10, NOx), noise | DALY of sleep disorders and annoyance | Mitigation | Impact assessment tools | Health impact assessment (HIA), Other environmental assessment tools * | WHO (HIA), Conseil fédéral Suisse (SA) | Assess the impacts of different GHG reduction measures | City | Geneva (Switzerland) | Yes |

| Garcia Menendez et al. [21] | 2015 | UNSP | Air pollution (Ozone, PM2.5) | Mortality | Mitigation (GHG reduction scenarios) | Nested models | UNSP | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | Allow an integrated analysis of the effects of CC mitigation measures on air pollution and health co-benefits | Country | United States | Yes |

| Haluza et al. [22] | 2012 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM10, NOx) | Cardiovascular and respiratory mortality | Mitigation (scenarios) | Other methodological approach | UNSP | Institute of Environmental Health, Center for Public Health, Medical University of Vienna | Region | Upper Austria | Yes | |

| Houghton et al. [23] | 2012 | Heatwaves, floods | Air temperature | Mortality (Cardiovascular, diabetes and hypertension) | Adaptation and Mitigation | Adaptation tools | Geospatial Emergency Management Support System (GEMSS) | Texas Water Development Board | City | Austin (USA) | No | |

| Houghton [24] | 2011 | Tornadoes, hurricanes, heat/drought, and lightning | Air temperature, wind | Mortality, injuries | Adaptation and Mitigation | Impact Assessment Tool | Health Impact Assessment | WHO | Assess climate change resilience in specific building projects | City | Houston (USA) | No |

| Kwan et al. [25] | 2016 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5), physical activity, and road crashes | Mortality | Mitigation | Impact Assessment Tool | Comparative Risk Assessment | WHO | Assess the co-benefits of a mass rapid transit project in terms of mortality reduction | City | Kuala Lumpur (Malaisia) | Yes |

| Li and Crawford-Brown [26] | 2011 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5 and PM10) | Cardiovascular and respiratory (asthma, bronchitis) mortality | Mitigation | Adaptation tools | UNSP | US EPA | Support decision-making using cost-benefit comparisons and health co-benefit assessments of air pollution reduction | City | Bangkok (Thailand) | Yes |

| Lindsay et al. [27] | 2011 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM10, NO2, CO), physical activity, road crash | Cardiovascular and respiratory (bronchitis) mortality | Mitigation | Other methodological approach | Combination of tools and survey data | University of Auckland | Estimate the effects on health, costs, air pollution, GHG emissions if short trips were undertaken by bicycle rather than car | Country | New Zealand | Yes |

| Markandya et al. [28] | 2009 | UNSP | Air pollution (CO2, PM2.5) | Mortality (cardiorespiratory disease and lung cancer), acute respiratory infections | Mitigation | Nested models | Three models (POLES, GAINS, and WHO Comparative Risk Assessment) | WHO | Assess modifications of particulate air pollution and health effects resulting from GHG reduction measures in the electricity generation sector | Countries | European Union, China and India | Yes |

| Perez et al. [29] | 2015 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5, elemental carbon), physical activity, noise | Mortality (noise, air pollution); DALY | Adaptation | Impact assessment tools | Health Impact Assessment | WHO | Assess the health impacts of local CC mitigation policies in the transport sector | City | Bâle (Switzerland) | Yes |

| Sarigiannis et al. [30] | 2017 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5, PM10, NO2, and benzene) | Mortality, DALY | Mitigation (GHG reduction) | Nested models | UNSP | Aristotle University of Thessaloniki | Assess health co-benefits associated with GHG reduction policies in transportation | City | Thessaloniki (Greece) | Yes |

| Smith and Haigler [31] | 2008 | Rising temperatures | Air pollution (methane, CO2) | DALY, years of life lost (YLL) | Mitigation | Other methodological approaches | UNSP | WHO | Assess health co-benefits associated with GHG reduction policies in the energy sector | Country | China | Yes |

| Smith et al. [32] | 2015 | Rising temperatures | Water and food | DALY | Adaptation | Conceptual framework | UNSP | Public Health Agency of Canada | Provide a scientific assessment of CC adaptation measures to support risk management of climatic events | Region | Hypothetical case | Yes |

| Thompson et al. [33] | 2016 | UNSP | Air pollution (ozone and PM2.5) | Mortality risk, morbidity (hospital admissions, emergency room visits, lost school days, acute respiratory symptoms, acute myocardial infarction (nonfatal heart attacks) and acute bronchitis) | Mitigation | Nested models | UNSP | US EPA (BenMAP) | Assess health and monetary impacts of a carbon policy at the subnational scale | Region | Northeast USA (17 States) | Yes |

| Tobollik et al. [34] | 2016 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5, elemental carbon) and noise | YLL, years lived with disability (YLD) | Mitigation | Impact assessment tool | Health Impact Assessment | WHO | Assess the health co-benefits of local CC mitigation policies in the transport sector | City | Rotterdam (Netherlands) | Yes |

| Tuomisto et al. [35] | 2015 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5) | Mortality, DALY | Mitigation | Nested models | Opasnet | URGENCHE (EU FP7 project) | Estimate health impacts of emissions due to heat and power consumption of buildings and give guidance on different climate mitigation options | Cities | Bâle (Switzerland), Kuopio (Finland) | Yes |

| Williams et al. [36] | 2018 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5, NO2 and ozone) | YLL | Mitigation | Nested models | UNSP | King’s College | Assess health co-benefits of different CC mitigation actions in the energy sector | Country | Great Britain | Yes |

| Wolkinger et al. [37] | 2018 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5, PM10 and NO2) | Mortality, hospital admissions, and years lived with disability for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Physical activity. | Mitigation | Nested models | UNSP | Center for Climate and Global Change, (Austria) | Allow a detailed health and macroeconomic assessment of CC adaptation policies | Cities | Graz, Vienna and Linz (Austria) | Yes |

| Woodcock et al. [38] | 2009 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5, PM10) | YLL, YLD, DALY, and mortality | Mitigation | Impact assessment tool | Comparative Risk Assessment | WHO | Compare the health effects of different mitigation scenarios with a reference situation | Cities | New Delhi (India); London, (United Kingdom) | Yes |

| Zhang et al. [39] | 2016 | UNSP | Air pollution (PM2.5) | Mortality and morbidity | Mitigation | Nested models | UNSP | Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development (Utrecht University) | Assess the potential for energy savings and emission mitigation of air pollution from China’s cement industry, and quantify the health co-benefits linked with air pollution reduction in this sector | Regions | China (all provinces) | Yes |

| (b) | ||||||||||||

| Author | Year | Climatic Event | Exposure | Health Issue | Strategy (Adaptation, Mitigation) | Tool Type | Name | Provider | Tool’s Objective | Scale | Area | Measure of the Health Effect |

| Rudolph et al. [40] | 2018 | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP | Mitigation | Conceptual framework | Climate, health, and equity vulnerability assessment | Public Health Institute Center for Climate Change and Health | Assess health and climate vulnerabilities | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP |

| UNFCCC [41] | 2011 | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP | Impact assessment tool | Health Impact Assessment | WHO, Curtin University WHO Collaborating Centre | Assess potential CC impacts and develop adaptation responses to support governmental decision making | UNSP | UNSP | Yes |

| WHO (Europe regional office) [42] | 2013 | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP | Adaptation | Adaptation tools | Health and adaptation costs | WHO | Support health adaptation planning in European states by estimating health and adaptation costs and efficiency of adaptation measures | Country | Europe | Yes |

| WHO [43] | 2003 | UNSP | UNSP | Mortality morbidity | Adaptation and Mitigation | Impact assessment tool | Quantitative health impact assessment | WHO | Quantify the burden of disease from specific risk factors and estimate the benefit of realistic interventions that remove or reduce risk factors | UNSP | UNSP | Yes |

| WHO [44] | 2013 | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP | Adaptation | Adaptation tools | Vulnerability and adaptation assessment | WHO | Provide guidelines to improve the elaboration of vulnerability and adaptation assessment and plan the adaptation of the health sector (similar to Health National adaptation process) | Country | UNSP | Yes |

| WHO [45] | 2014 | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP | Adaptation | Adaptation tools | Health National adaptation process | WHO | Ensure that the process of iteratively managing the health risks of climate change is integrated into the overall National Adaptation Plan process to achieve the goals of healthy people in healthy communities | Country | Directed to developing countries and least-developed countries | Yes (indicators) |

| Ontario government [46] | 2016 | UNSP | UNSP | UNSP | Adaptation | Adaptation tools | Vulnerability and adaptation assessment | WHO | Support a resilient and adaptive public health system to anticipate, take into account, and attenuate the emerging risks and impacts of CC (similar to National health adaptation process) | Province | Ontario, Canada | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delpla, I.; Diallo, T.A.; Keeling, M.; Bellefleur, O. Tools and Methods to Include Health in Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies and Policies: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052547

Delpla I, Diallo TA, Keeling M, Bellefleur O. Tools and Methods to Include Health in Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies and Policies: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052547

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelpla, Ianis, Thierno Amadou Diallo, Michael Keeling, and Olivier Bellefleur. 2021. "Tools and Methods to Include Health in Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies and Policies: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052547

APA StyleDelpla, I., Diallo, T. A., Keeling, M., & Bellefleur, O. (2021). Tools and Methods to Include Health in Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies and Policies: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052547