Abstract

The retention of key human resources is a challenge and a necessity for any organisation. This paper analyses the impact of the existence and accessibility of work-family policies on the well-being of workers and their intention to leave the organisation. To test the proposed hypotheses, we applied a structural equation model based on the partial least squares path modelling (PLS-SEM) approach to a sample of 558 service sector workers. The results show that the existence and accessibility of work-family policies directly reduce the intention to leave the organisation. Moreover, this relationship also occurs indirectly, by mediating the well-being that is generated by these work-family policies. We also analysed the moderating role that gender and hierarchy could have in the above relationships. In addition to the above theoretical implications, this study has practical implications. The findings show that employees with family and work balance problems experience lower emotional well-being, more health problems and eventually higher turnover rates. To avoid these problems, management must focus not only on the implementation of work-family policies but also on their accessibility, without subsequent retaliation or prejudice to employees. Additionally, management should pay special attention to female managers, given their greater difficulty in balancing work and family life.

1. Introduction

Experienced and well-trained professionals who leave their organisations are a major problem for management []. Retaining key employees, who are fundamental to the growth and development of organisations, is both a challenge and a necessity []. Managing the turnover intention of these employees is vital to the survival of organisations, especially in the service industry [], since high turnover rates can mean high costs [] and organisations lose the investments made in training, development and retention when valuable employees leave. In addition, it is necessary to retrain new employees to replace those who have left []. For this reason, some human resource management practices aim at retaining workers by reducing their turnover intention []. These practices include work-family policies (WFPs). WFPs are human resources practices that organisations implement to promote and facilitate work-family balance []. Some examples of WFPs would be flexible working hours, teleworking, breastfeeding leave, and financial support for childcare [].

The determinants of turnover intention include work-related stress [,], job dissatisfaction [,,], harassment at work [,], burnout syndrome [], lack of commitment to the organisation [], and work-family conflict (WFC) [,]. The WFC arises when it is difficult to balance workers’ work and personal lives []. This difficulty, coupled with the ongoing demand for improved outcomes, puts strong psychological pressures on workers []. As a result, the WFC can lead to job stress, negative performance effects and worker turnover [].

Organisations aim to reduce the impact of WFC by implementing WFPs that mitigate it [] and ultimately prevent job abandonment. The implementation of WFPs reduces work stress [], absenteeism [], and turnover intention []. In addition, WFPs improve job satisfaction [], quality of life [,], and workers’ emotional commitment [,]. WFPs also have the virtue of reducing the negative effects of WFC on the psychological and physical well-being of workers []. For this reason, well-being can act as a mediator between WFPs and other variables such as work performance [,], absenteeism [], and, predictably, turnover intention.

Nevertheless, the mere existence of WFPs does not imply that employees can enjoy these policies without inconvenience []. For workers to be able to access WFPs without problems, they must be aware of them [] and perceive that they can use them freely without retaliation [,]. The concept of WFP accessibility is the degree of freedom perceived by workers to use the WFPs offered by their organisation without undermining their career, working conditions, social and professional respect and income [].

The literature sufficiently recognises the relationship between WFC and turnover [,]. However, there is a knowledge gap in the study of the impact of WFPs []. In addition, the separate analysis of the relationships of the existence and accessibility of WFPs with turnover and the mediating role of employees’ well-being in these relationships are also novel. In this regard, the aim of the present study is to analyse the impact that the existence and accessibility of WFPs have on turnover intention while considering the mediating effect that well-being has on this relationship. To achieve this objective, we tested these relationships using a structural equation model based on the partial least squares path modelling (PLS-SEM) approach to a sample of 558 service sector workers. The study of WFC and the implementation of WFPs deserves special attention in the service sector [], where workers commonly suffer from work-related stress [], which ultimately increases WFC and turnover prevalence.

The results of this study provide, as an added value to the literature on WFPs, a separate analysis of the effect that the existence and accessibility of these policies have on the well-being and turnover intention. In addition, we study how the emotional and physical well-being of employees influences turnover rates. Finally, we analyse the moderating role that gender and hierarchy might have in the above relationships. The interest in studying gender and hierarchy as moderating variables is supported by works that recommend implementing WFPs to avoid WFC for women with responsibilities in the organisation []. Similarly, Sharabi [] adds the importance of reducing WFC for women managers through specific WFPs, such as flexitime and teleworking.

This paper is structured as follows. Section two sets out the theoretical framework that supports the relationships between the existence and accessibility of WFPs, well-being and turnover intention. Section three describes the methodology that has been developed, in that we define the variables and their measures, and apply a structural equation model to the data that were collected from a service sector sample. In section four, the results show that all of the model assumptions are congruent with the postulated sign and all are supported. Furthermore, we found that the mediating effects of emotional and physical well-being are significant. This section also studies the moderating role of gender and the hierarchy. Finally, we discuss and conclude the results of the study.

2. Background and Hypotheses

In this section, we present the theoretical foundations of the model of the effect of WFPs on turnover intention, mediated by well-being. The development of this model provides the hypotheses under study.

2.1. WFPs and Turnover

According to Role Theory, job satisfaction reduces when there are work and family conflict [] and this negative relationship has been confirmed empirically by several studies [,], with inter-role conflict being considered as a predictor of the level of job satisfaction []. More specifically, work interference in the family reduces the level of employees’ satisfaction [] and this conflicting situation encourages employees to leave their organisations [,]. This phenomenon is even more pronounced in the case of long weekly working hours []. In this regard, studies consider WFC to be a significant predictor of turnover intention [].

The WFPs that organisations implement to reduce WFC increase employee commitment to their organisations [], thus decreasing the intention to leave []. Notwithstanding, the literature with studies of WFPs based on appraisal and coping theory [] indicates that WFPs have a positive correlation with job satisfaction, and reduce stress, deliberate wrong task performance and even abandonment of work [,]. Therefore, solving the WFC contributes to increasing job satisfaction and reducing the probability of employees leaving their jobs []. In addition, the existence of WFPs increases workers’ loyalty and commitment to their organisations [], which also reduces turnover rates [].

However, WFPs must be properly implemented if they are to definitively avoid certain behaviours that are counterproductive to the organisation and to a lesser degree, avoid abandonment []. Although WFPs can help reduce turnover, the mere existence of WFPs is not enough. To the best of our knowledge, previous research often forgets that these WFPs must also be accessible to the worker. For WFPs to generate the expected advantages, workers should know that they exist [], but they should also perceive that WFPs are accessible without retaliation or adverse consequences for their careers []. Otherwise, workers may not use WFPs for fear of a perceived lack of commitment to the organisation, losing promotion opportunities or even their jobs []. Since the mere existence of WFPs is not sufficient [], we should separately consider whether workers are aware of the existence of WFPs and whether they also perceive that they are accessible in practice.

On the basis of all the above arguments, we propose two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The existence of WFPs is negatively related to turnover intention.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The accessibility of WFPs is negatively related to turnover intention.

2.2. WFPs and Emotional Well-Being

WFC is a stress factor, as work responsibilities interfere with employees’ family responsibilities when they are forced to spend more time and energy on their work than on their family []. As argued by Role Conflict Theory [], an individual’s time and energy are limited. The resources spent on the employee’s role exhaust the resources that are available for the family role, thus creating conflict []. In this regard, previous studies in the literature associate WFC with burnout and psychological stress [,], which in turn reduces the emotional well-being of the worker []. On the other hand, WFPs can generate emotional well-being [,,,,], since reducing WFC would have positive effects on people’s happiness [] and would decrease negative emotions []. Further, lack of, or difficulty in accessing, WFPs is related to mental health issues such as anxiety and depression [,,]. Based on these arguments, we establish the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The existence of WFPs is positively related to the emotional well-being of employees.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The accessibility of WFPs is positively related to the emotional well-being of employees.

2.3. Emotional Well-Being and Physical Well-Being

Emotional and psychological problems can seriously affect health [,]. According to Gong et al. [], problems at work such as stress and burnout that are maintained over time can eventually lead to psychological problems. Moreover, the type of work and the extension of the working day reduces or even eliminates physical activity, both inside and outside the workplace [] generating adverse effects such as disorders of the musculoskeletal system [], obesity [] and diabetes []. In this regard, inadequate management causes some of the workers’ illnesses, as management demands on workers can lead to increased work-related and personal stress []. Further, stress, in turn, causes psychosocial and physical problems, leading to a deterioration in workers’ health [].

Based on the above, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Emotional well-being is positively related to physical well-being.

2.4. Physical Well-Being and Turnover Intention

Stress, anxiety and a lack of emotional well-being can lead to physical exhaustion and other physical problems, such as nausea, muscular pain, and cardiovascular disease, among others [,,,,]. These health problems and lack of physical well-being reduce workers’ performance and increase their possible intention to leave the organisation [,,].

Health problems and general physical discomfort can lead to functional difficulties, lack of capacity for adequate performance or even sick leave for workers. Nevertheless, one of the most common side effects of the lack of physical well-being is a decrease in employee motivation and organisational commitment, factors that increase turnover intention []. For this reason, retaining employees means improving motivation, which in turn requires improving their physical well-being [,].

The above arguments lead to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Physical well-being of the worker is negatively related to turnover intention.

2.5. Gender and Hierarchy Moderating Effect

The literature on the WFC shows that women experience more difficulty than men in balancing [,]. Working women carry a double burden as employees, as housewives and as primary caregivers [,]. In this regard, WFC is higher in women than in men as a result of the overload of family care, specifically for children and the elderly []. The work-life balance is more complex for women, as they find it harder to ignore family problems, especially children’s concerns [,]. The previous literature on women’s dual roles predicts that the existence and accessibility of WFPs will be more crucial to women, so WFPs impact on well-being and turnover intention may be different from that of men. However, there is also evidence that gender does not influence turnover intention []. These contradictory results could be the case in some situations because of the influence of cultural and sectoral determinants on this phenomenon [,].

However, the impact of WFPs may also depend on the position in the organisational hierarchy. In this regard, the greater the responsibility at work, the higher the level of WFC a worker might experience [,]. Thus, being a woman and a manager is a double challenge, which makes it particularly complex to balance work and family life [].

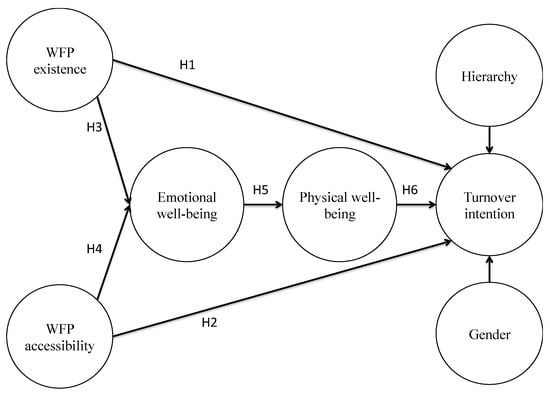

Given the relevance of this research question, this paper considers the moderating role that gender and the hierarchy might have in the above hypotheses. Considering the relations previously established in the hypotheses and the moderating role of gender and hierarchy noted above, Figure 1 depicts the theoretical model proposed for verification.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model and hypotheses.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

The sample obtained was made up of 584 workers from the Spanish service sector. We collected data by conducting a self-administered questionnaire survey. We emailed the participants a link to an online form. Managers collaborated in the survey process, prescribing their employees to participate and allowing them to complete the questionnaires during working hours. Considering the large number of emails sent, the response rate was 14.7%. The number of participating companies was thirteen. These companies included financial companies, IT companies, insurance companies, contact centres and, to a lesser extent, engineering companies, healthcare companies, retail companies and companies in the tourism sector.

Applying the pre-evaluation of the data proposed by Hair et al. [], we removed 26 observations due to their high percentage of missing data. Therefore, we carried out the study with 558 valid questionnaires. Of the total number of respondents, 45.3% were women, of whom 16.1% were managers, 68.0% had university studies, and the average age was 44.8 years. Other relevant characteristics that describe the sample are that 90.4% had a partner, 78.5% of whom both worked; 74.1% had a child, and 47.1% had two or more children; 23.5% had a dependent ascendant, and 5.2% had a disabled dependant. Considering the time worked, 18.1% had less than ten years of experience in the company, 42.3% had less than 20 years, and the remaining 39.6% had more than 20 years. Most of the contracts were stable, with only 3.4% being temporary. In terms of average weekly working hours, only 9.6% reported working up to a maximum of 30 h, 55.8% worked an average of up to 40 h, and 34.6% more than 40 h per week. Concerning working shifts, 51.1% worked only morning shifts, 39.7% worked morning and afternoon shifts, and the remaining 9.2% worked afternoon or night shifts, or variable shifts.

We divided the sample into four subsamples to analyse the interaction effect of gender and hierarchy variables, namely: (1) female managers, (2) female employees, (3) male managers, and (4) male employees, composed of 34, 219, 56 and 249 individuals, respectively.

Given that the statistical power of the sample is 0.8 and that the default alpha level is 0.05, we can say that the sample (n = 558) made it possible to detect very small effect sizes, which were difficult to identify [].

3.2. Measures

We modelled the variables included in the theoretical model as composites, since they were design variables formed by the linear combination of the indicators. In addition, since the indicators were correlated, we designed all the variables as composite in mode A, using the correlation weights [].

We used various indicators that assessed the degree of agreement of respondents with various statements using a 7-point Likert scale. These indicators or items were intended to reflect the subjective assessment made by the respondents of the variables of the theoretical model of this research.

We defined the variable existence of WFPs as the subjective perception of individuals that WFPs exist in their organisation. To measure the existence of WFPs, we adopted five items from the Families and Work Institute [,] scale, namely: (Regarding WFPs) (1) “Your organisation offers them”; (2) “Your organisation reports on them”; (3) “Know what they consist of”; (4) “You have ever used them”; and (5) “Know employees who have used them”.

As aforementioned, the concept of WFP accessibility is the degree of freedom perceived by individuals to use the WFPs offered by their organisation without undermining their career, working conditions, social and professional respect and income. The accessibility of WFPs combined the contributions of Anderson, Coffey and Byerly [] and the Families and Work Institute [,] into fifteen items, that were: (Considering the use of WFPs) (1*) “The application procedures are simple”; (2) “There is an unwritten rule in my job that an employee cannot attend to family or personal needs during work hours”; (3) “At my workplace, employees who put their family or personal needs ahead of their jobs are not well regarded”; (4) “If you have a problem combining your work responsibilities with family and personal ones, the attitude in my work is: It was your decision, now accept the consequences”; (5*) “When I am offered more hours than stipulated in the employment contract, I can refuse to work them without negative consequences at work”; (6) “In my workplace, employees have to choose between advancing their careers or devoting their attention to their personal or family lives”; (7) “In my workplace, employees who apply for permits or licenses for family or personal reasons, or who agree to different schedules for personal or family needs, are less likely to advance in their jobs or careers”; (8*) “I have the flexible working hours I need at work to manage my personal and family responsibilities”; (If I were to apply to use WFPS...) (9*) “My work responsibilities do not allow it”; (10) “There would be negative consequences regarding advancing my professional career”; (11) “There would be negative consequences regarding my current or future income”; (12) “My superior would not support it”; (13) “My colleagues would not support it”; (14*) It would mean that others would have to do more work; (15) “They would make me appear to be less committed to my job or career”. Subsequently, we removed from the measurement scale the items having a number marked with an asterisk (*).

We defined emotional well-being as a positive psychological, affective and mental health state of individuals. We measured the emotional well-being variable by integrating Warr [] and Kossek et al. [] scales into a reflective fifteen-item scale, which was: (“During the last few weeks, I’ve felt all the time....”) (1) “Tense”; (2) “Uneasy”; (3) “Preoccupied”; (4) “Calm”; (5) “Content”; (6) “Relaxed”; (7) “Depressed”; (8) “Sad”; (9) “Unhappy”; (10) “Cheerful”; (11) “Enthusiastic”; (12) “Optimistic”; (13) “Angry”; (14) “Annoyed”; and (15) “Irritated”.

We defined individuals’ physical well-being as the absence of diseases and the development of behaviours to prevent them from having a healthy lifestyle and sufficient energy to fulfil their obligations at work. To measure physical well-being, we used a nine-item scale from the study of Kossek et al. [], namely: (“During the last few weeks, I’ve felt all the time....”) (1) “Annoying trembling of my hands”; (2) “Shortness of breath when not working physically or hard”; (3) “Pounding heart”; (4) “Faster-than-normal pounding of my heart”; (5) “Sweat on my hands, feeling wet and sticky”; (6) “Momentary dizziness”; (7) “Stomach ache or upset”; (8) “Loss of appetite”; and (9) “Problems with sleeping at night”.

Turnover intention measures whether an organisation’s employees plan to leave their jobs or whether that organisation plans to remove employees from their jobs. In this paper, we only considered employee turnover intention. We measured turnover intention with a scale of eight items from the work of Boshoff and Mels [], Becker [], and De Cuyper, Mauno, Kinnunen, and Mäkikangas [], that was: (1) “I will probably actively look for another job soon”; (2) “I often think about resigning”; (3) “It would not take much to make me resign”; and (4) “There is not too much to be gained by sticking with the organisation indefinitely”.

Finally, we measured the moderating variables of gender (male/female) and hierarchy (worker/manager) dichotomously. In the case of the hierarchy variable, we considered managers to be those who held positions of responsibility or who were in charge of other workers.

3.3. Structural Equation Modelling

We proposed a SEM model based on the aforementioned PLS-SEM approach, to test the hypotheses. We followed the methodological guidelines of Hair Jr, Sarstedt, Hopkins, and Kuppelwieser [] to provide consistent estimations as we have variables modelled as composites. In this analysis, we used SmartPLS software (SmartPLS GmbH, Bönningstedt, Germany) [].

We evaluated the model by following these steps: assessment of the global model, assessment of the measurement model, assessment of the structural model and finally, analysis of the moderating effect.

3.4. Common Method Bias

Common method bias, or common-method variance, is a false variance caused by measuring variables using the same method or source []. To study this problem, we used the full collinearity test based on variance inflation factors (VIF) following Kock []. According to this test, a VIF value higher than 3.3 would mean that there is a pathological co-linearity, which would imply that the common method bias contaminates the model. In our study, the highest value was 1.54, hence the model was free of bias.

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of the Global Model

The goodness of the global model fit was the first step for the assessment of the model. If the model did not fit the data, the estimates obtained may be without meaning and therefore the conclusions may be opened to dispute []. We made two assessments of the global model. The first assessment considered all of the indicators in the model before the assessment of the measurement model. The second assessment followed the measurement model study and the removal of indicators that did not fulfil the requirements.

For the analysis of the global model, we used the approximate adjustment measures []. To be precise, we analysed the standardised root mean squared residual (SRMR), whose threshold was 0.8 []. The results showed values of 0.074 before the removal of the indicators and 0.060 after the removal of these indicators. Therefore, the model was better after the removal of the indicators which presented reliability and validity problems. In conclusion, we were able to state that we had an approximately true model.

4.2. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

Since the model contained composites estimated in Mode A, we analysed the reliability and validity. The reliability analysis checks that the indicators measured what they should measure, while the validity analysis verified that the measurement was stable and consistent.

Firstly, an analysis of the individual reliability of the item was done, in which a great quantity of the indicators with their respective constructs was examined. We considered the threshold proposed by Carmines and Zeller [], which accepts items with loads higher than 0.707. Notwithstanding, some researchers suggest not eliminating items with loads between 0.4 and 0.707, in case they do not formulate problems for the rest of the stages of the measurement model []. We had to remove three items corresponding to the accessibility of WFPs with very low loads (below 0.4). Subsequently, we removed two more items in this variable to fulfil the requirement for convergent validity. As a result, we managed to increase the value of the average variance extracted (AVE). As for the turnover intention variable, we eliminated four indicators with very low loads.

Secondly, we closely studied the reliability of the construct in order to determine if the items measuring a construct were similar in their scores. For this purpose, we considered the measures corresponding to composite reliability [] and Dijkstra-Henseler []. Nunnally and Bernstein [] suggest values higher than 0.8 for more advanced stages of research.

Subsequently, we studied the convergent validity to check that the indicators represented a single subjacent construct. This occurred when the AVE had values above 0.5 [].

Finally, we verified discriminant validity, i.e., the degree to which a given construct was different from other constructs. Table 1 shows this check utilising the HTMT ratio []. We also checked this discriminant validity by employing the criterion of Fornell and Larcker [], using the matrix of correlations between variables.

Table 1.

Measurement model. Discriminant validity. HTMT ratio (Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio).

Once we had removed the items described above, the model met the necessary reliability and validity requirements. Table 1 and Table 2 reflect these results. Correlation weights indicated the contribution of each indicator to the composite. The weights allowed us to check the reliability of the item in the model. Although we noted that one of the weights did not reach the minimum required threshold (λ >= 0.707), the construct reliability (Composite reliability and Dijkstra-Henseler’s (ρA)) was greater than 0.7 and the convergent validity (AVE) was greater than 0.5 in the corresponding latent variable, hence it was not necessary to remove it.

Table 2.

Results of the measurement model.

4.3. Structural model

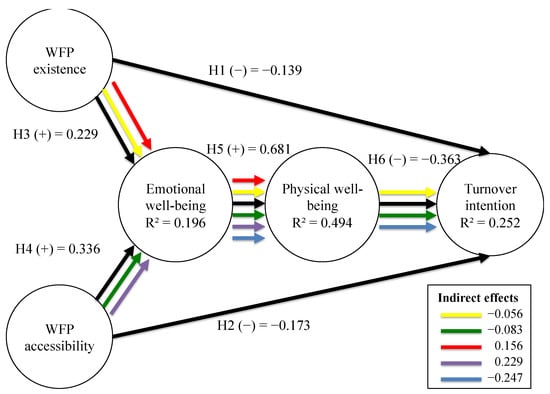

For the assessment of the structural model, we studied closely the relationships raised in the model utilising the bootstrap method with 5000 samples. Along these lines, we assessed the magnitude, sign and significance of the relationships between the variables. In addition, we analysed the model predictive power by means of the coefficient of determination (R²) of the endogenous variables and the decomposition of the explained variance. This permitted us to know the relevance of each of the antecedent variables in the dependent variable. Finally, we used the rules from Cohen [] to determine the size of the effects. These outcomes are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

Direct effects. Hypotheses.

Figure 2.

Direct effects. Diagram.

The R² values obtained in this model indicated a low predictive power for the dependent variables emotional well-being and turnover intention, and a moderate predictive power for the variable physical well-being. The postulated sign made all the relationships of the theoretical model congruent, supported with a small effect for hypotheses H1, H2, H3 and H4, and with a moderate effect for hypothesis H6 and a large effect for hypothesis H5. Finally, we could prove that the mediating effects of the model were significant. Therefore, we could conclude that the variables emotional well-being and physical well-being mediate within the proposed model (Table 4 and Figure 3).

Table 4.

Indirect effects. Mediation.

Figure 3.

Indirect effects. Diagram.

4.4. Moderating Effect

Finally, we tested the interaction effect of the moderating variable associated with gender and hierarchy by conducting a multi-group analysis. For this purpose, a division of the sample into four different groups was made: female managers, female employees, male managers and male employees. Firstly, we analysed the invariance of the measure to make sure that the parameters of the measurement model were not the reason for these differences, but rather the reason was linked to the path coefficients. We found partial invariance in two cases, total invariance in two other cases and in the further two cases the invariance of the measure was not met (Table 5). Therefore, for the latter cases, we could not apply the permutation analysis that was developed by Chin [] to evaluate whether there were significant differences between each pair of groups. We carried out the permutation analysis in the four cases where there was invariance of the measure (Table 6), and we realised that there were only significant differences in the WFPs’ existence and emotional well-being relationship, for the groups “female managers” and “female employees”, and the groups “female managers” and “male employee”.

Table 5.

Results of the measurement invariance assessment (MICOM).

Table 6.

Multi-group analysis based on the permutation test.

5. Discussion

The findings of this paper have theoretical implications with respect to the body of the literature and also practical implications for business management.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Regarding the theoretical implications, the results obtained reinforce and update the existing evidence in the literature about the negative relationship between WFPs and turnover []. In fact, these results are coherent with that part of the literature which proves the relationship between WFC and stress, performance and turnover []. In contrast, some authors do not see a direct or indirect relationship between WFC and turnover []. If this were the case, the implementation of WFPs to retain valuable staff would not be sufficiently justified. However, our findings are aligned with the literature that does recognise the negative relationship between WFPs and turnover.

In this paper, we analyse the accessibility and existence of WFPs separately. This differentiation allows us to study the impact of these two variables on turnover intention independently. This differentiation adds further value to the literature on WFPs. The results of our work consider that the mere existence of WFPs does not imply a decrease in turnover intention. In addition to the existence of WFPs, these WFPs must be accessible to workers without subsequent retaliation, or detriment to their economic incentives or professional career.

The results of this work also indicate positive relationships between the existence and accessibility of WFPs and the emotional well-being of employees. This relationship is consistent with the literature on the effects of WFPs on well-being []. Notwithstanding, these findings reinforce those provided by Medina-Garrido et al. []. As with those authors, we confirm that the mere existence of WFPs is not enough to have a positive impact on workers’ emotional well-being, but it is also necessary that these WFPs are accessible to workers.

Our research also corroborates that there is a significant relationship between emotional well-being and physical well-being of employees and that these two variables mediate between WFPs and turnover intention. In line with the literature, these findings confirm the negative relationship between well-being and turnover [,]. As examples in the literature point out, in practice, the absence of adequate WFPs can generate WFC, thus decreasing emotional well-being. This may lead to stress and anxiety in workers [] and subsequently to health problems [,,], thus contributing to increased turnover intention [,].

Regarding the moderating variables of gender and hierarchy, we observed significant differences in the existence of WFPs and the emotional well-being relationship between the “female manager” and “female employees” groups, and also between the “female managers” and “male employees” groups. The literature on WFPs does not describe these differences, hence they add value to the previous literature. Moreover, this result is consistent with the literature that generally argues on the particular difficulty female managers have in balancing family and work-life []. This result seems to suggest that female managers have more difficulties than other groups in achieving adequate emotional well-being.

5.2. Practical Implications for Management

The results of our study also have practical implications for management. If the managers of an organisation want to improve the emotional well-being of their workers and reduce WFC-motivated turnover, then the introduction of WFPs would be a necessary but not sufficient condition. Complementarily, employees should have access to WFPs without reprisals of any kind. Their possibilities of promotion within the organisation and their financial incentives should not be threatened. In this regard, the organisation should show its explicit support for the balance of family and personal life with working life. To this end, the organisation should disseminate a culture of acceptance of work-life balance which prevents social sanctions that would imply disapproval by colleagues and supervisors. We recommend carefully planning the process of implementing WFPs, starting with their proper selection. The WFPs that management should pay more attention to are those that are most valued by employees as a means of balancing work and family. In our research, the most valued measures were the following, in this order: flexible working hours, reduced working hours for child and family care, breastfeeding leave hours, personal leave days, long-term leave for family illness, leave for hospitalisation of a partner or relative, leave to accompany a family member for medical care, long-term leave to care for family and children, and transfer to the work centre closest to the family home.

After implementing the WFPs, the management should monitor that they are working correctly and that workers can access those WFPs without any inconvenience. In this regard, we suggest that management should establish a balanced scorecard, or similar monitoring tool, to compare the implementation objectives and the effective use of each practice. Periodic monitoring of this balanced score-card will ensure the correct functioning and use of the practices or highlight the need to intervene to correct any deviations.

In addition, given the vital role of well-being in reducing turnover intention, managers should be aware that employees with work-life balance problems may suffer from health problems, besides feeling lower emotional well-being. Managers should realise that turnover intention can increase not only because of employees’ difficulties in balancing family and work but also because they can subsequently suffer from stress, anxiety and even physical health problems.

Finally, managers should consider, for the specific case of female managers, the moderating role of gender and hierarchy in the relationship between existing WFPs and emotional well-being. We recommend that organisations pay special attention to female managers. This group experiences greater difficulty in balancing, compared to other groups. Moreover, female managers may have less emotional well-being. This is because they have to balance family responsibilities with management responsibilities. The latter is more demanding responsibilities with a higher level of stress and commitment than for other employees.

6. Conclusions

Retaining experienced and well-trained employees is a challenge and a vital need for many organisations [] but a major determinant of job abandonment is WFC [], hence reducing this conflict requires organisations to implement WFPs.

This paper aims to analyse the impact that WFPs have on reducing turnover intention. To achieve this objective, we propose a model in which the existence and accessibility of WFPs are negatively related to turnover intention, mediated sequentially by emotional well-being and physical well-being and moderated by gender and hierarchy. We contrast these relationships using a structural equation model based on the PLS-SEM approach to a sample of 558 service sector workers. As a result, all of the proposed relationships are verified, except in the case of moderation, where we only see significant differences between some groups in the relationship between the WFPs’ existence and emotional well-being.

The findings of this paper have theoretical implications for the literature and also practical implications for business management. From a theoretical point of view, we confirm that WFPs and well-being have a negative relationship with turnover intention. Furthermore, we found that both the existence of WFPs and their accessibility have an impact on emotional well-being and turnover intention. We also corroborate that there is a significant relationship between emotional well-being and physical well-being of employees and that these two variables mediate the relationship between WFPs and turnover intention. Finally, we found significant differences in the WFPs’ existence and emotional well-being relationship between “female managers” and “female employees” groups and also between “female managers” and “male employees” groups.

These theoretical findings have important practical implications. Given the results obtained, we recommend that managers take care not only of the implementation of WFPs but also of their accessibility. Regarding the implementation of WFPs, management should pay more attention to the WFPs that are most valued by employees to balance work and family. Once WFPs are in place, management should monitor that they are working correctly (e.g., using a balanced score-card or similar monitoring tool). Concerning the accessibility of WFPs, workers should perceive that the use of WFPs does not lead to retaliation or further damage. Managers should show their express support for the use of such WFPs and spread a culture of acceptance of work-life balance. In addition, managers should be aware that employees with work-life balance problems could experience a reduction in their emotional well-being and also suffer from health problems. The latter, in turn, could increase turnover intention. Finally, we recommend that organisations pay special attention to female managers. This group experiences greater difficulty in achieving work-life balance, compared to other groups.

Among the possible limitations of this study would be that the sample used belongs to the Spanish service sector; i.e., one country and one sector. Although the findings obtained are significant, this sample could suffer a particular bias that would limit the generalisation of the results at a global level and for other sectors. In this regard, a future line of work to overcome this limitation would be to replicate this study in other industries and countries. This would allow us to overcome the bias and compare different sectoral, cultural, economic and socio-demographic contexts.

Comparison between groups considering hierarchy could also be a limitation of this work as the number of managers surveyed was much lower than the number of employees. We recommend expanding the sample of managers in future studies to allow confirmation of the results obtained here but comparing groups of similar size.

Finally, we suggest another future line of research for analysis with, on the one hand, assessment of what the role of WFC could be in the theoretical model proposed in this paper and, on the other hand, assessment of whether there is a significant relationship between the existence and accessibility of WFPs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation of materials, J.A.M.-G. and J.M.B.-F.; development of questionnaire and fieldwork, J.A.M.-G. and J.M.B.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.M.-G., J.M.B.-F., and M.V.R.-C.; writing—review and editing, J.A.M.-G.; statistics and outcome, J.A.M.-G. and J.M.B.-F.; funding acquisition, J.A.M.-G., J.M.B.-F., and M.V.R.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research institute INDESS and the Department of Business Organisation of the Universidad de Cádiz partially funded the APC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval are not applicable in this case since this study does not concern health, physical or mental safety or the processing of private personal data of human beings. The questionnaires collected did not include data that posed ethical risks and were collected anonymously.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not applicable to this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the fact that access to them requires express and unique approval for each occasion.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Pasewark, W.R.; Viator, R.E. Sources of Work-Family Conflict in the Accounting Profession. Behav. Res. Account. 2006, 18, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeba, F. The Role of Data Analytics in Talent Acquisition and Retention with Special Reference to SMEs in India: A Conceptual Study. IUP J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 18, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.; Jagirani, T.S. Employee Turnover in Public Sector Banks of Pakistan. Mark. Forces 2019, 14, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vidal, M.E.; Cegarra-Leiva, D.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.G. ¿Influye el conflicto trabajo-vida personal de los empleados en la empresa? Universia Bus. Rev. 2011, 29, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Somaya, D.; Williamson, I.O. Rethinking the “War for Talent”. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2008, 49, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gullekson, N.L.; Griffeth, R.; Vancouver, J.B.; Kovner, C.T.; Cohen, D. Vouching for childcare assistance with two quasi-experimental studies. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 994–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Sanchez, A.; Perez-Perez, M.; Vela-Jimenez, M.J.; Abella-Garces, S. Job satisfaction and work–family policies through work-family enrichment. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Garrido, J.A.; Biedma-Ferrer, J.M.; Ramos-Rodríguez, A.R. Relationship between work-family balance, employee well-being and job performance. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2017, 30, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heponiemi, T.; Presseau, J.; Elovainio, M. On-call work and physicians’ turnover intention: The moderating effect of job strain. Psychol. Heal. Med. 2016, 21, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.S. The Relationship Between Human Resource Management Practices, Organizational Commitment, Career Concern, Job Stress and Turnover Intention. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tziner, A.; Rabenu, E.; Radomski, R.; Belkin, A. Work stress and turnover intentions among hospital physicians: The mediating role of burnout and work satisfaction. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2015, 31, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulachai, W.; Amaraphibal, A. Developing a causal model of turnover intention of police officers in the eastern region of Thailand. Int. J. Arts Sci. 2017, 10, 473–486. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.K.C. Perspective on the Influence of Leadership on Job Satisfaction and Lower Employee Turnover in the Mineral Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heponiemi, T.; Elovainio, M.; Presseau, J.; Eccles, M.P. General practitioners’ psychosocial resources, distress, and sickness absence: A study comparing the UK and Finland. Fam. Pract. 2014, 31, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuluaga, M.; Andrea, P.; Moreno Moreno, S. Relation between burnout syndrome, coping strategies and engagement. Psicol. Desde Caribe 2012, 29, 206–229. [Google Scholar]

- Nasution, M.I. Turnover intention medical representative. Mix J. Ilm. Manaj. 2017, 7, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Roche, M.; Taylor, D. Work-family conflict and turnover intentions of indigenous employees: The importance of the whanau/family for Maori. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2546–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hu, X.-M.; Huang, X.-L.; Zhuang, X.-D.; Guo, P.; Feng, L.-F.; Hu, W.; Chen, L.; Zou, H.; Hao, Y.-T.; et al. The relationship between job satisfaction, work stress, work-family conflict, and turnover intention among physicians in Guangdong, China: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, 14894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A. The relationship between work/family demands, personality and work-family conflict. Bus. Rev. J. 2013, 21, 272–277. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I.-H.; Brown, R.; Bowers, B.J.; Chang, W.-Y. Work-to-family conflict as a mediator of the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 2350–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Kotrba, L.M.; Mitchelson, J.K.; Clark, M.A.; Baltes, B.B. Antecedents of work-family conflict: A meta-analytic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 689–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, C.G.; Colombo, L.; Ghislieri, C. Determinants of nurses’ job satisfaction: The role of work-family conflict, job demand, emotional charge and social support. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Garrido, J.A.; Biedma-Ferrer, J.M.; Sánchez-Ortiz, J. I Can’t Go to Work Tomorrow! Work-Family Policies, Well-Being and Absenteeism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suifan, T.S.; Abdallah, A.B.; Diab, H. The influence of work life balance on turnover intention in private hospitals: The mediating role of work life conflict. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 8, 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, K.B.; Yang, G. The Effects of Family-Friendly Policies on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: A Panel Study Conducted on South Korea. Public Pers. Manage. 2017, 46, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda, L.; Ollo-López, A.; Goñi-Legaz, S. Family-friendly practices, high-performance work practices and work-family balance How do job satisfaction and working hours affect this relationship? Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2016, 14, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi-Legaz, S.; Ollo-López, A. The Impact of Family-Friendly Practices on Work–Family Balance in Spain. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2016, 11, 983–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, R.; Desiana, P.M. The Impact of Owners’ Intrinsic Motivation and Work-Life Balance on SMEs’ Performance: The Mediating Effect of Affective Commitment. Int. J. Bus. 2019, 24, 393–411. [Google Scholar]

- Anita, R.; Abdillah, M.R.; Wu, W.; Sapthiarsyah, M.F.; Sari, R.N. Married Female Employees’ Work-Life Balance and Job Performance: The Role of Affective Commitment. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 28, 1787–1806. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W.G.M. Subjective well-being in organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K.S., Spreitzer, G.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Garrido, J.A.; Biedma-Ferrer, J.M.; Ramos-Rodríguez, A.R. Moderating effects of gender and family responsibilities on the relations between work–family policies and job performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Parish, S.L. Family-supportive workplace policies and South Korean mothers’ perceived work-family conflict: Accessibility matters. Asian Popul. Stud. 2020, 16, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönlund, A.; Öun, I. In search of family-friendly careers? Professional strategies, work conditions and gender differences in work–family conflict. Community Work Fam. 2018, 21, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, N.; Zawawi, D.; Aziz, Y.A.; Ali, M.H. Work-family conflict and job performance: Moderating effect of social support among employees in malaysian service sector. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 21, 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M.; Shamshir, M.; Khan, K. Association of work-life balance and job satisfaction in commercial pilots: A case study of Pakistan. Indep. J. Manag. Prod. 2020, 11, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.K.; Kuan, N.Y.; Yang, F.C.; Hing, L.Y.; Yaw, W.K. Occupational Stress among Women Managers. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2017, 9, 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Sharabi, M. Work, family and other life domains centrality among managers and workers according to gender. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 1307–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R.L.; Wolfe, D.M.; Quinn, R.P.; Snoek, J.D.; Rosenthal, R.A. Organizational stress: Studies in Role Conflict and Ambiguity; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, S.; Tremblay, D.-G. Work–family conflict/family–work conflict, job stress, burnout and intention to leave in the hotel industry in Quebec (Canada): Moderating role of need for family friendly practices as “resource passageways”. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2399–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urs, L.; Schmidt, A.M. Work-family conflict among IT specialty workers in the US. Community Work Fam. 2018, 21, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, F.; Russo, M.; Ferrara, M. Work–family conflict and job insecurity: Are workers from different generations experiencing true differences? Community Work Fam. 2015, 18, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Allen, T.D.; Poelmans, S.A.Y.; Lapierre, L.M.; Cooper, C.L.; Michael, O.; Sanchez, J.I.; Abarca, N.; Alexandrova, M.; Beham, B.; et al. Cross-national differences in relationships of work demands, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions with work-family conflict. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 805–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautsch, B.A.; Scully, M.A. Restructuring time: Implications of work-hours reductions for the working class. Hum. Relat. 2007, 60, 719–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Ryu, S. Employee Satisfaction with Work-life Balance Policies and Organizational Commitment: A Philippine Study. Public Adm. Dev. 2017, 37, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.A.; Prottas, D.J. Relationships among organizational family support, job autonomy, perceived control, and employee well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.J.; Park, S.; Joshanloo, M.; Kim, M. Work–Family Spillover and Subjective Well-Being: The Moderating Role of Coping Strategies. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 2909–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Maldonado, A.; Salanova, M. Evolución de los modelos sobre el afrontamiento del estrés: Hacia el coping positivo. Àgora Salut Vol. III 2016, 3, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. Work Cultures and Work/Family Balance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.B.; McKechnie, S.; Swanberg, J. Predicting employee engagement in an age-diverse retail workforce. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorakian, A.; Nosrati, S.; Eslami, G. Conflict at work, job embeddedness, and their effects on intention to quit among women employed in travel agencies: Evidence from a religious city in a developing country. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan, T.T.; Singh, B.; Cloninger, P.A.; Misra, K. Work–family conflict and counterproductive work behaviors: Moderating role of regulatory focus and mediating role of affect. Organ. Manag. J. 2019, 16, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, T.A.; Henry, L.C. Making the link between work-life balance practices and organizational performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, G. Supported Employment: Evidence for an Evidence-Based Practice. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2004, 27, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, J.W.; Mumford, K.A. Family-Friendly Work Practices in Britain: Availability and Perceived Accessibility. IDEAS Work. Pap. Ser. RePEc 2006, 45, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Saksvik, P.Ø. Work-Family Conflict and Psychosocial Work Environment Stressors as Predictors of Job Stress in a Cross-Cultural Study. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2008, 15, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of Conflict Between Work and Family Roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutek, B.A.; Searle, S.; Klepa, L. Rational versus gender role expectations for family-work conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, P.; O’Driscoll, M.P.; Kalliath, T.J. The ability of “family friendly” organizational resources to predict work-family conflict and job and family satisfaction. Stress Heal. 2005, 21, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Qureshi, H.; Frank, J.; Keena, L.D.; Hogan, N.L. The relationship of work-family conflict with job stress among Indian police officers: A research note. Police Pract. Res. 2017, 18, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantanen, J.; Kinnunen, U.; Feldt, T.; Pulkkinen, L. Work-family conflict and psychological well-being: Stability and cross-lagged relations within one- and six-year follow-ups. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia-Casademunt, A.M.; Ariza-Montes, J.A.; Morales-Gutiérrez, A.C. Determinants of occupational well-being among executive women. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2013, 26, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, L.; Allen, T. Work-Supportive Family, Family-Supportive Supervision, Use of Organizational Benefits, and Problem-Focused Coping: Implications for Work–Family Conflict and Employee Well-Being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Molineux, J.; Mirshekary, S.; Scarparo, S. Developing individual and organisational work-life balance strategies to improve employee health and wellbeing. Empl. Relat. 2015, 37, 354–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Figueroa, A.; Moyano Díaz, E. Factores laborales de equilibrio entre trabajo y familia: Medios para mejorar la calidad de vida. Universum 2008, 23, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Psychosocial Risks and Stress at Work. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/themes/psychosocial-risks-and-stress (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Moreno Jiménez, B. Factores y riesgos laborales psicosociales: Conceptualización, historia y cambios actuales. Med. Segur. Trab. 2011, 57, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Han, T.; Yin, X.; Yang, G.; Zhuang, R.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Z. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and work-related risk factors among nurses in public hospitals in southern China: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiling, Q.; Moyle, W.; Jones, C.; Weeks, B. Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being in Older University Office Workers: Survey Findings. Workplace Health Saf. 2019, 67, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshmandi, H.; Choobineh, A.; Ghaem, H.; Karimi, M. Adverse effects of prolonged sitting behavior on the general health of office workers. J. lifestyle Med. 2017, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Schnall, P.; Yang, H.; Dobson, M.; Landsbergis, P.; Israel, L.; Karasek, R.; Baker, D. Sedentary Work, Low Physical Job Demand, and Obesity in US Workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmot, E.G.; Edwardson, C.L.; Achana, F.A.; Davies, M.J.; Gorely, T.; Gray, L.J.; Khunti, K.; Yates, T.; Biddle, S.J.H. Sedentary Time in Adults and the Association with Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and Death: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; Springer: Heidelberg/Berlin, Germany, 2012; ISBN 0012-186X. [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos, G. Vigilancia epidemiológica de los factores psicosociales. Aproximación conceptual y valorativa. Cienc. Trab. 2004, 14, 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, E. Relaciones de intercambio en las organizaciones y riesgos psicosociales: Un estudio sobre la relación del contrato psicológico y el burnout (desgaste ocupacional) en una muestra de empleados mexicanos. In Psicología del Trabajo. Un Entorno de Factores Psicosociales Saludables para la Productividad; Uribe, J.F., Ed.; Manual Moderno: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2016; pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O.; Karadas, G. The effect of psychological capital on conflicts in the work–family interface, turnover and absence intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 43, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timms, C.; Brough, P.; O’Driscoll, M.; Kalliath, T.; Siu, O.L.; Sit, C.; Lo, D. Flexible work arrangements, work engagement, turnover intentions and psychological health. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2015, 53, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; Agarwal, U.A. Exploring Work-Life Balance among Indian Dual Working Parents: A Qualitative Study. J. Manag. Res. 2017, 17, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Billing, T.K.; Bhagat, R.S.; Babakus, E.; Krishnan, B.; Ford, D.L.; Srivastava, B.N.; Rajadhyaksha, U.; Shin, M.; Kuo, B.; Kwantes, C.; et al. Work-Family conflict and organisationally valued outcomes: The moderating role of decision latitude in five national contexts. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 63, 62–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, S.; Navarro, J.; Yepes, M.; Berger, R.; Romero, M. La auditoría del sistema humano (ASH) para el análisis del comportamiento humano en las organizaciones. Papeles Psicólogo 2008, 29, 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhya, K.; Kumar, D. Employee retention by motivation. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2011, 4, 1778–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Bhatnagar, D. Linking emotional dissonance and organizational identification to turnover intention and emotional well-being: A study of medical representatives in India. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 49, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukrowska-Torzewska, E. Cross-Country Evidence on Motherhood Employment and Wage Gaps: The Role of Work–Family Policies and Their Interaction. Soc. Polit. 2017, 24, 122–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Collins, K.; Shaw, J. The relation between work-family balance and Quality of Life. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annink, A.; Dulk, L. Autonomy: The panacea for self-employed women’s work-life balance? Community 2012, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggesi, S.; Mari, M.; De Vita, L. Women entrepreneurs and work-family conflict: An analysis of the antecedents. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otálora Montenegro, G. La relación existente entre el conflicto trabajo-familia y el estrés individual en dos organizaciones colombianas. Cuad. Adm. 2007, 20, 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Boeckmann, I.; Misra, J.; Budig, M. Cultural and Institutional Factors Shaping Mothers’ Employment and Working Hours in Postindustrial Countries. Soc. Forces 2014, 93, 1301–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanch, A.; Aluja, A. Social support (family and supervisor), work–family conflict, and burnout: Sex differences. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 811–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. Gender Differences in Voluntary Turnover: Still a Paradox? Int. Bus. Res. 2012, 5, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinamon, R.G. Anticipated work-family conflict: Effects of gender, self-efficacy, and family background. Career Dev. Q. 2006, 54, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainer, C.D.; Subramaniam, C.; Arokiasamy, L. Determinants of Turnover Intention in the Private Universities in Malaysia: A Conceptual Paper. SHS Web Conf. 2018, 56, 03004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781483377445. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Social Sciences; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J. Bridging design and behavioral research with variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Families and Work Institute. Benchmarking Report on Workplace Effectiveness and Flexibility—Executive Summary; Families and Work Institute: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Families and Work Institute. Workplace Effectiveness and Flexibility Benchmarking Report; Families and Work Institute: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.E.; Coffey, B.S.; Byerly, R.T. Formal Organizational Initiatives and Informal Workplace Practices: Links to Work–Family Conflict and Job-Related Outcomes. J. Manage. 2002, 28, 787–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Colquitt, J.A.; Noe, R.A. Caregiving decisions, well-being, and performance: The effects of place and provider as a function of dependent type and work-family climates. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshoff, C.; Mels, G. The Impact of Multiple Commitments on Intentions to Resign: An Empirical Assessment. Br. J. Manag. 2000, 11, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.E. Foci and Bases of Commitment: Are They Distinctions Worth Making? Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cuyper, N.; Mauno, S.; Kinnunen, U.; Mäkikangas, A. The role of job resources in the relation between perceived employability and turnover intention: A prospective two-sample study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 78, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, F.J., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt SmartPLS GmbH. Available online: http//www.smartpls.com (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS Path Modeling in New Technology Research: Updated Guidelines. Ind. Manag. & Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines, E.G.; Zeller, R.A. Reliability and Validity Assessment; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Werts, C.E.; Linn, R.L.; Jöreskog, K.G. Intraclass reliability estimates: Testing structural assumptions. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. The assessment of reliability. Psychom. Theory 1994, 3, 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. A permutation procedure for multi-group comparison of PLS models. In PLS and Related Methods: Proceedings of the International Symposium PLS’03; Vilares, M., Tenenhaus, M., Coelho, P., Esposito Vinzi, V., Morineau, A., Eds.; Decisia: Lisbon, Portugal, 2003; Volume 3, pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Post, E.P.; Kilbourne, A.M.; Bremer, R.W.; Solano, F.X.; Pincus, H.A.; Reynolds, C.F. Organizational factors and depression management in community-based primary care settings. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raina, R.; Roebuck, D.B. Exploring Cultural Influence on Managerial Communication in Relationship to Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and the Employees’ Propensity to Leave in the Insurance Sector of India. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2016, 53, 97–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afenyo, S.K. The Effect of Motivation on Retention of Workers in the Private Sector: A Case Study of Zoomlion Company Ghana Ltd. Ph.D. Thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ashanti, Ghana, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hassard, J.; Teoh, K.R.H.; Visockaite, G.; Dewe, P.; Cox, T. The cost of work-related stress to society: A systematic review. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).