Interaction Structures in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy for Adolescents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Evidence Base and IS for PDT in Adolescents

1.2. Aims of the Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Therapists

2.4. Treatment Adherence

2.5. Measures

2.6. Procedures

2.7. Data–Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Extraction of IS

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Partial Correlations

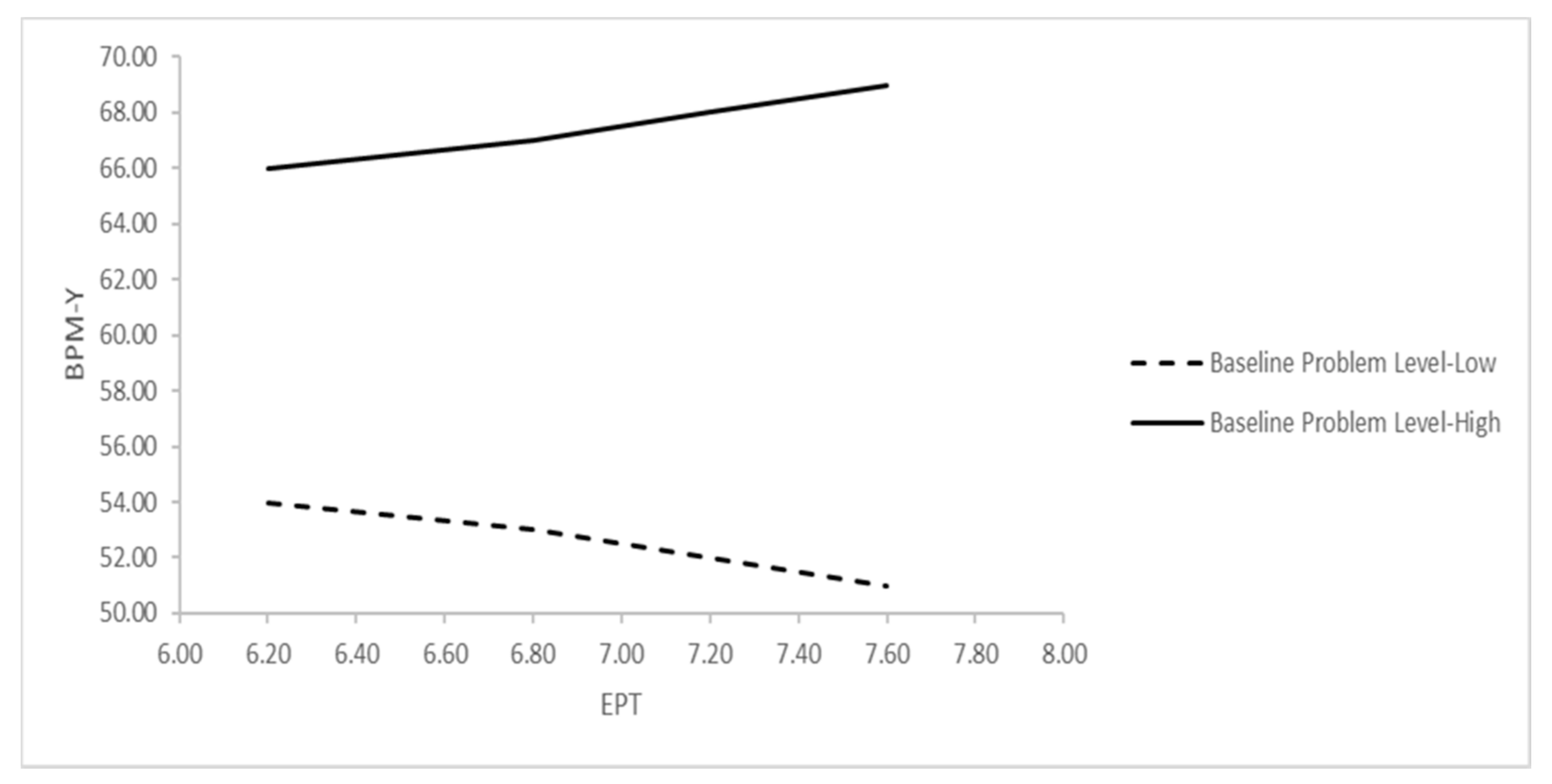

3.3. MLM Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical and Research Implications

4.2. Study Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| IS 1: Negative Therapeutic Alliance | ||

| Item | Loading | Description |

| 15 | 0.681 | YP does not initiate or elaborate topics |

| 7 | 0.669 | YP is anxious or tense |

| 44 | 0.609 | YP feels wary or suspicious of the T |

| 30 | 0.559 | YP has difficulty beginning the session |

| 12 | 0.523 | Silences occur during the session |

| 20 | 0.503 | YP is provocative, tests limits of therapy relationship |

| 1 | 0.496 | YP expresses, verbally or nonverbally, negative feelings toward the T |

| 42 | 0.448 | YP rejects T’s comments and observations |

| 23 | −0.471 | YP is curious about the thoughts, feelings, or behavior of others |

| 24 | −0.478 | YP demonstrates capacity to link mental states with action or behavior |

| 28 | −0.482 | YP communicates a sense of agency |

| 74 | −0.575 | Humor is used |

| 13 | −0.627 | YP is animated or excited |

| 95 | −0.654 | YP feels helped by the therapy |

| 72 | −0.684 | YP demonstrates lively engagement with thoughts and ideas |

| 73 | −0.785 | YP is committed to the work of therapy |

| IS 2: Demanding Patient, Accommodating Therapist | ||

| Item | Loading | Description |

| 87 | 0.757 | YP is controlling of the interaction with the T |

| 83 | 0.669 | YP is demanding |

| 78 | 0.602 | YP seeks T’s approval, affection, or sympathy |

| 14 | 0.528 | YP does not feel understood by T |

| 93 | 0.501 | T refrains from taking position in relation to YP’s thoughts or behavior |

| 89 | 0.461 | T makes definite statements about what is going on in the YP’s mind |

| 47 | 0.421 | When the interaction with YP is difficult, T accommodates in an effort to improve relations |

| 51 | 0.411 | YP attributes own characteristics or feelings to T |

| 37 | 0.401 | T remains thoughtful when faced with YP’s strong affect or impulses |

| 29 | −0.408 | YP talks about wanting to be separate or autonomous from others |

| 80 | −0.439 | T presents an experience or event from a different perspective |

| 54 | −0.458 | YP is clear and organized in self-expression |

| 33 | −0.609 | T adopts a psychoeducational stance |

| IS 3: Emotionally Distant Resistant Patient | ||

| Item | Loading | Description |

| 58 | 0.565 | YP resists T’s attempts to explore thoughts, reactions, or motivations related to problems |

| 53 | 0.507 | YP discusses experiences as if distant from his feelings |

| 10 | 0.500 | YP displays feelings of irritability |

| 67 | 0.495 | YP finds it difficult to concentrate or maintain attention during the session |

| 2 | 0.426 | T draws attention to YP’s nonverbal behavior |

| 22 | −0.404 | YP expresses feelings of remorse |

| 59 | −0.408 | YP feels inadequate and inferior |

| 32 | −0.459 | YP achieves a new understanding |

| 6 | −0.487 | YP describes emotional qualities of the interactions with significant others |

| 94 | −0.504 | YP feels sad or depressed |

| 41 | −0.514 | YP feels rejected or abandoned |

| 9 | −0.525 | T works with YP to try to make sense of experience |

| 26 | −0.660 | YP experiences or expresses troublesome (painful) effects |

| 8 | −0.722 | YP expresses feelings of vulnerability |

| IS 4: Inexpressive Patient, Inviting Therapist | ||

| Item | Loading | Description |

| 77 | 0.501 | T encourages YP to attend to somatic feelings or sensations |

| 61 | 0.496 | YP feels shy or self-conscious |

| 57 | 0.430 | T explains rationale behind technique or approach to treatment |

| 100 | 0.405 | T draws connections between the therapeutic relationship and other relationships |

| 52 | −0.448 | YP has difficulty with ending of sessions |

| 34 | −0.465 | YP blames others or external forces for difficulties |

| 88 | −0.539 | YP fluctuates between strong emotional states during the session |

| 55 | −0.641 | YP feels unfairly treated |

| 84 | −0.770 | YP expresses angry or aggressive feelings |

| IS 5: Exploratory Psychodynamic Technique (EPT) | ||

| Item | Loading | Description |

| 65 | 0.632 | T restates or rephrases YP’s communication in order to clarify its meaning |

| 99 | 0.579 | T raises questions about YP’s view |

| 3 | 0.545 | T’s remarks are aimed at facilitating YP’s speech |

| 97 | 0.533 | T encourages reflection on internal states and affects |

| 18 | 0.511 | T conveys a sense of nonjudgmental acceptance |

| 39 | 0.468 | T encourages YP to reflect on symptoms |

| 46 | 0.452 | T communicates with YP in a clear, coherent style |

| 31 | 0.407 | T asks for more information or elaboration |

| 66 | −0.408 | T is directly reassuring |

| 76 | −0.413 | T explicitly reflects on own behavior, words or feelings |

| 21 | −0.417 | T self-discloses |

| 85 | −0.484 | T encourages YP to try new ways of behaving with others |

| 81 | −0.575 | T reveals emotional responses |

| 43 | −0.618 | T suggests the meaning of others’ behavior |

| 49 | −0.618 | There is discussion of specific activities or tasks for the YP to attempt outside of session |

| 27 | −0.626 | T offers explicit advice and guidance |

References

- Abbass, A.A.; Rabung, S.; Leichsenring, F.; Refseth, J.S.; Midgley, N. Psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of short-term psychodynamic models. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolsc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midgley, N.; Kennedy, E. Psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents: A critical review of the evidence base. J. Child Psychother. 2011, 37, 232–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, N.; O’Keeffe, S.; French, L.; Kennedy, E. Psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents: An updated narrative review of the evidence base. J. Child Psychother. 2017, 43, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, N.; Mortimer, R.; Cirasola, A.; Batra, P.; Kennedy, E. The evidence-base for psychodynamic psychotherapy with children and adolescents: A narrative synthesis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R.; Nascimento, L.N.; Fonagy, P. The state of the evidence base for psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 22, 149–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Midgley, N. Research in child and adolescent psychotherapy: An overview. In The Handbook of Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy. Psychoanalytic Approaches, 2nd ed.; Lanyado, M., Horne, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Calderon, A.; Midgley, N.; Schneider, C.; Target, M. Adolescent Psychotherapy Q-Set. Coding Manual; Unpublished Manuscript; Anna Freud Centre, University College London: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.E. Therapeutic Action: A Guide to Psychoanalytic Therapy; Aronson: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.; Jones, E.E. Child Psychotherapy Q-Set. Coding Manual; Unpublished Manual; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Calderon, A.; Schneider, C.; Target, M.; Midgley, N. The adolescent psychotherapy Q-Set (APQ): A validation study. J. Infant Child Adolesc. Psychother. 2017, 16, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, G.; Athey-Lloyd, L. Interaction structures between a child and two therapists in the psychodynamic treatment of a child with Asperger’s disorder. J. Child Psychother. 2011, 37, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.E.; Ghannam, J.; Nigg, J.T.; Dyer, J.F.P. A paradigm for single-case research: The time series study of a long-term psychotherapy for depression. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1993, 61, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramires, V.R.R.; Carvalho, C.; Polli, R.G.; Goodman, G.; Midgley, N. The therapeutic process in psychodynamic therapy with children with different capacities for mentalizing. J. Infant Child Adolesc. Psychother. 2020, 19, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, G.; Fearon, P. The evaluation of mental health outcome at a community-based psychodynamic psychotherapy service for young people: A 12-month follow-up based on self-report data. Psychol. Psychother. 2002, 75, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronmüller, K.; Stefini, A.; Geiser-Elze, A.; Horn, H.; Hartmann, M.; Winklemann, K. The Heidelberg study of psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents. In Assessing Change in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy of Children and Adolescents; Tsiantis, J., Trowell, J., Eds.; Karnac: London, UK, 2010; pp. 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Mensi, M.M.; Orlandi, M.; Rogantini, C.; Borgatti, R.; Chiappedi, M. Effectiveness of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in preadolescents and adolescents affected by psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelmann, K.; Stefini, A.; Hartmann, A.; Geizer-Elze, A.; Kronmüller, A.; Schenkenbach, C.; Hildegard, H.; Kronmüller, K.T. Efficacy of psychodynamic and short-term psychotherapy for children and adolescents with behavior disorders. Prax. Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiatr. 2005, 54, 598–614. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer, I.; Tasncheva, S.; Byford, S.; Dubika, B.; Hill, J.; Raphael, K.; Reynolds, S.; Roberts, C.; Senior, R.; Sucking, J.; et al. Improving Mood with Psychoanalytic and Cognitive Therapies (IMPACT): A pragmatic effectiveness superiority trial to investigate whether specialized psychological treatment reduces the risk for relapse in adolescents with moderate to severe unipolar depression. Trials 2011, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodyer, I.M.; Reynolds, S.; Barrett, B.; Byford, S.; Dubicka, B.; Hill, J.; Holland, F.; Kelvin, R.; Midgley, N.; Roberts, C.; et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytical psychotherapy versus a brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depressive disorder (IMPACT): A multicentre, pragmatic, observer-blind, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calderon, A.; Schneider, C.; Target, M.; Midgley, N. ‘Interaction structures’ between depressed adolescents and their therapists in short-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grossfeld, M.; Calderon, A.; O’Keefe, S.; Green, V.; Midgley, N. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy with a depressed adolescent with borderline personality disorder: An empirical, single case study. J. Child Psychother. 2019, 45, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, M.; Maggiolini, A. Research on adolescent psychotherapy process: An Italian contribution to the adolescent psychotherapy Q-set (APQ). J. Infant Child Adolesc. Psychother. 2019, 18, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, S.; Goodman, G.; Bulut, P. Interaction structures as predictors of outcome in a naturalistic study of psychodynamic child psychotherapy. Psychother. Res. 2020, 30, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, S. Psychodynamic technique and therapeutic alliance in prediction of outcome in psychodynamic child psychotherapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 89, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.E.; Cumming, J.D.; Horowitz, M.J. Another look at the nonspecific hypothesis of therapeutic effectiveness. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile; Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L.A. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles; Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families, University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg, P.F.; Ritvo, R.; Keable, H. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI). Practice parameter for psychodynamic psychotherapy with children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 51, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bychkova, T.; Hillman, S.; Midgley, N.; Schneider, C. The psychotherapy process with adolescents: A first pilot study and preliminary comparisons between different therapeutic modalities using the Adolescent Psychotherapy Q-Set. J. Child Psychother. 2011, 37, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, N.; Simsek, Z. Mental health of Turkish children: Behavioral and emotional problems reported by parents, teachers, and adolescents. In International Perspectives on Child and Adolescent Mental Health: Proceedings of the First International Conference; Singh, N.N., Leung, J.P., Singh, A.N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Ivanova, M.; Rescorla, L. Manual for the ASEBA Brief Problem Monitor™ (BPM); ASEBA: Burlington, VT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, v26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rasbash, J.; Steele, F.; Browne, W.J.; Goldstein, H. A User’s Guide to MLwiN, v5.0; Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, W.J.; Draper, D. A comparison of Bayesian and likelihood-based methods for fitting multilevel model. Bayesian Anal. 2006, 1, 473–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Subramanian, S.V. Developing Multilevel Models for Analyzing Contextuality, Heterogeneity and Change Using MLwiN; Center for Multilevel Modeling, University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky, L. Principles of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A Manual for Supportive-Expressive Treatment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbard, G.O. Long-Term Psychodynamic Psychotherapy; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks-Carter, C.; Muran, C.J.; Safran, J.D. Alliance-focused training. Psychotherapy 2015, 52, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, P.B.; Jones, E.E. Examining the alliance using the psychotherapy Q-set. Psychotherapy 1998, 35, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blos, P. The second individuation process of adolescence. Psychoanal. Study Child 1967, 22, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity and Crisis; Faber & Faber: London, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D.W.; Winnicott, C.; Shepherd, R.; Davis, M. Home Is Where We Start From: Essays by a Psychoanalyst; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mishne, J.M. Therapeutic challenges in clinical work with adolescents. Clin. Soc. Work 1996, 24, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrell, R.D.; Paulson, B.L. The therapeutic alliance: Adolescent Perspectives. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2002, 2, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, K.; Cartwright, C.; Kerrisk, K.; Campbell, J.; Seymour, F. What young people want: A qualitative study of adolescents’ priorities for engagement across psychological services. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, N.; Holmes, J.; Parkinson, S.; Stapley, E.; Eatough, V.; Target, M. “Just like talking to someone about like shit in your life and stuff, and they help you”: Hopes and expectations for therapy among depressed adolescents. Psychother. Res. 2016, 26, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Midgley, N.; Reynolds, S.; Kelvin, R.; Loades, M.; Calderon, A.; Martin, P.; The IMPACT Consortium; O’Keeffe, S. Therapists’ techniques in the treatment of adolescent depression. J. Psychother. Integr. 2018, 28, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, S. Working with Adolescents: A Contemporary Psychodynamic Approach; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken, M.; Haltigan, J.D.; Szatmari, P.; Dubicka, B.; Fonagy, P.; Kelvin, R.; Midgley, N.; Reynolds, S.; Wilkinson, P.O.; Goodyer, I.M. Toward precision therapeutics: General and specific factors differentiate symptom change in depressed adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, S.; Martin, P.; Goodyer, M.; Kelvin, R.; Dubicka, B.; Midgley, N. Prognostic implications for adolescents with depression who drop out of psychological treatment during a randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 58, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, P.; Holgersen, H.; Nielsen, G.H. Re-establishing contact: A qualitative exploration of how therapists work with alliance ruptures in adolescent psychotherapy. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2008, 8, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.; Hilsenroth, M.J. Interaction between alliance and technique in predicting patient outcome during psychodynamic psychotherapy. J. Nerv. Ment. Des. 2011, 199, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersoug, A.G.; Ulberg, R.; Hoglend, P. When Is transference work useful in psychodynamic psychotherapy? Main results of the first experimental study of transference work (FEST). Contemp. Psychoanal. 2014, 50, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) BPM-Y | 60.619 | 8.472 | − | |||||

| (2) IS 1 | 4.101 | 0.710 | −0.033 | − | ||||

| (3) IS 2 | 4.460 | 0.500 | −0.111 | 0.180 | − | |||

| (4) IS 3 | 4.519 | 0.523 | −0.126 | 0.350 * | 0.248 | − | ||

| (5) IS 4 | 4.949 | 0.550 | −0.120 | 0.346 * | 0.026 | 0.244 | − | |

| (6) IS 5 (EPT) | 7.348 | 0.353 | 0.149 | −0.361 * | −0.322 * | −0.134 | −0.251 | − |

| Intercept and Predictors | BPM-Y | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% Credible Interval | |

| Intercept (β00) | 59.798 ** | 0.789 | 58.246; 61.352 |

| Sex (β01) | −1.176 | 1.109 | −3.337; 1.001 |

| Age (β02) | −0.451 | 0.309 | −1.039; 0.167 |

| YSR (β03) | 0.727 ** | 0.051 | 0.627; 0.832 |

| IS 1 (β10) | 0.402 | 0.681 | −0.935; 1.743 |

| IS 2 (β20) | 0.040 | 0.745 | −1.443; 1.510 |

| IS 3 (β30) | −1.257 | 0.780 | −2.830; 0.251 |

| IS 4 (β40) | −0.325 | 0.736 | −1.775; 1.132 |

| IS 5 (EPT) (β50) | 0.061 | 1.153 | −2.227; 2.334 |

| IS 5 (EPT) × YSR (β53) | 0.180 * | 0.102 | −0.016; 0.383 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Can, B.; Halfon, S. Interaction Structures in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy for Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13007. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413007

Can B, Halfon S. Interaction Structures in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy for Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13007. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413007

Chicago/Turabian StyleCan, Barış, and Sibel Halfon. 2021. "Interaction Structures in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy for Adolescents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13007. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413007

APA StyleCan, B., & Halfon, S. (2021). Interaction Structures in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy for Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13007. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413007