Motivation to Move Out of the Community as a Moderator of Bullying Victimization and Delinquent Behavior: Comparing Non-Heterosexual/Cisgender and Heterosexual African American Adolescents in Chicago’s Southside

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.4. Analysis Plan

3. Results

4. Multivariate Model Results

4.1. Results Based on the Total Sample

4.2. Results Based on Subgroup Analyses

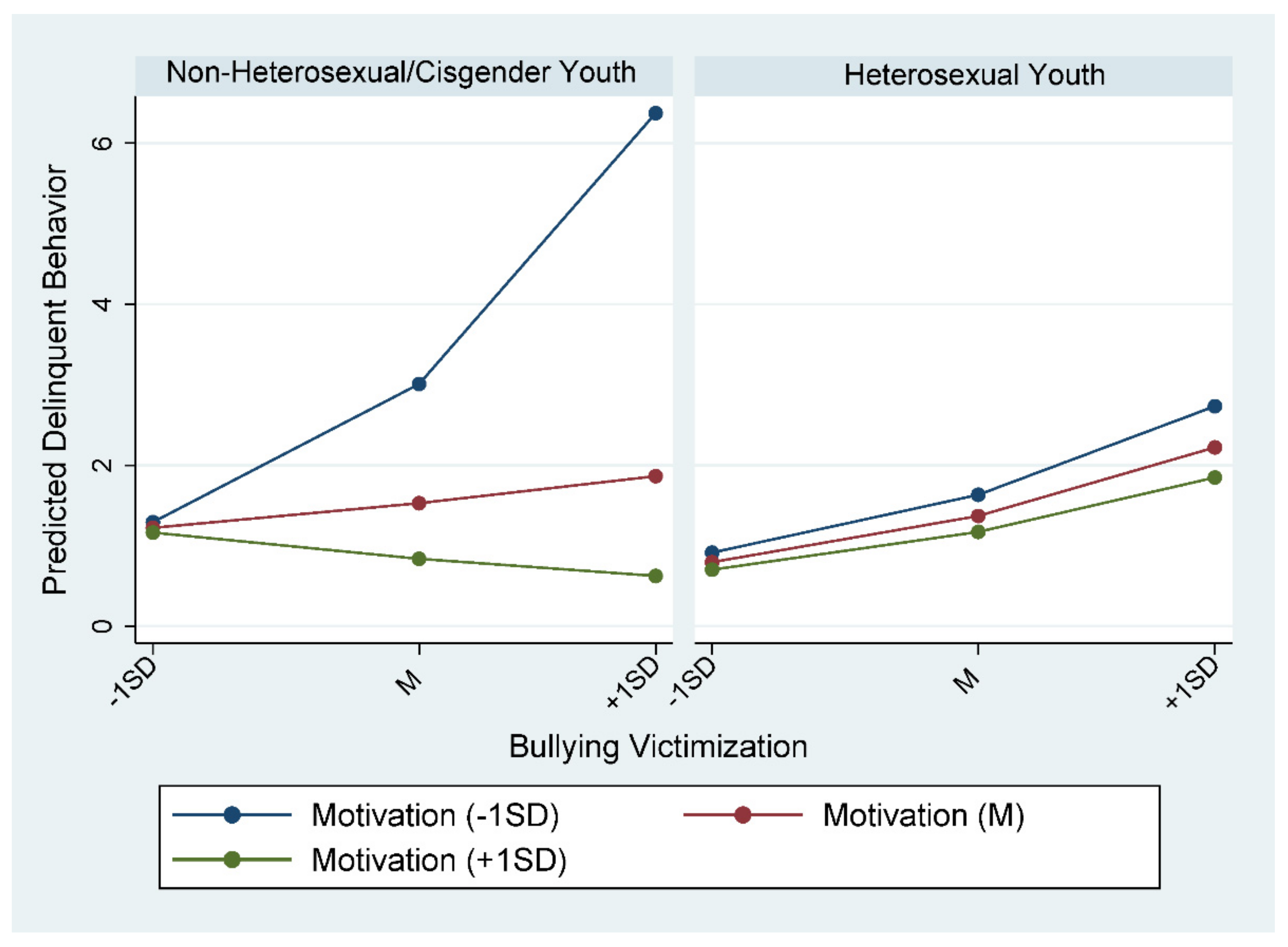

4.3. Moderating Effect Illustration

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations and Implications for Research

5.2. Implications for Theory and Practice

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Graham, S. Peer victimization in school: Exploring the ethnic context. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 15, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosciw, J.G.; Clark, C.M.; Truong, N.L.; Zongrone, A.D. The 2019 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation’s Schools, Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN): New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Koo, D.J.; Peguero, A.A.; Shekarkhar, Z. Gender, immigration, and school victimization. Vict. Offenders 2012, 7, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nansel, T.R.; Overpeck, M.; Pilla, R.S.; Ruan, W.J.; Simons-Morten, B.; Scheidt, P. Bullying behaviors among U.S. youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA 2001, 285, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitoroulis, I.; Vaillancourt, T. Meta-analytic results of ethnic group differences in peer victimization. Aggress. Behav. 2015, 41, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Jung, S.H. Ethnic differences in bullying victimization and psychological distress: A test of an ecological model. J. Adolesc. 2017, 60, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). Preventing Bullying through Science, Policy, and Practice; National Academies Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.T.; Sinclair, K.O.; Poteat, V.P.; Koenig, B.W. Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2013, 1, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, J.M.; Schick, V.; Romijnders, K.; Bauldry, J.; Butame, S. Social support, depression, self-esteem, and coping among LGBTQ adolescents participating in Hatch Youth. Health Promot. Pract. 2017, 18, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.L.; Eliason, M. Coming-out process related to substance use among gay, lesbian and bisexual teens. Brown Univ. Dig. Addict. Theory Appl. 2002, 24, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, G.E.; Khey, D.N.; Dawson-Edwards, B.C.; Marcum, C.D. Examining the link between being a victim of bullying and delinquency trajectories among an African American sample. Int. Crim. Justice Rev. 2012, 22, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Metcalfe, C. Bullying victimization as a strain: Examining changes in bullying victimization and delinquency among Korean students from a developmental general strain theory perspective. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2020, 57, 31–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassner, S.D.; Cho, S. Bullying victimization, negative emotions, and substance use: Utilizing general strain theory to examine the undesirable outcomes of childhood bullying victimization in adolescence and young adulthood. J. Youth Stud. 2018, 21, 1232–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuddy, T.; Esbensen, F.A. After the bell and into the night: The link between delinquency and traditional, cyber-, and dual-bullying victimization. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2017, 54, 409–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology 1992, 30, 47–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Felson, M. Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1979, 44, 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezina, T. Adapting to strain: An examination of delinquent coping responses. Criminology 1996, 34, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Pressured into Crime: An Overview of General Strain Theory; Roxbury: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McCrea, K.T.; Richards, M.; Quimby, D.; Scott, D.; Davis, L.; Hart, S.; Thomas, A.; Hopson, S. Understanding violence and developing resilience with African American youth in high-poverty, high-crime communities. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 99, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Rosenthal, R.; Carroll-Scott, A.; Peters, S.M.; McCaslin, C.; Ickovics, J.R. Teacher involvement as a protective factor from the association between race-based bullying and smoking initiation. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2014, 17, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Espelage, D.L.; Valido, A.; Hatchel, T.; Ingram, K.M.; Huang, Y.; Torgal, C. A literature review of protective factors associated with homophobic bullying and its consequences among children & adolescents. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 45, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.S.; Valido, A.; Rivas-Koehl, M.; Wade, R.M.; Espelage, D.L.; Voisin, D.R. Bullying victimization, psychosocial functioning, and protective factors: Comparing African American heterosexual and sexual minority adolescents in Chicago’s Southside. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 1358–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardaway, C.R.; McLoyd, V.C. Escaping poverty and securing middle class status: How race and socioeconomic status shape mobility prospects for African Americans during the transition to adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culyba, A.J.; Zbebe, K.Z.; Albert, S.M.; Jones, K.A.; Paglisotti, T.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Miller, E. Association of future orientation with violence perpetration among male youths in low-resource neighborhoods. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 877–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J.L.; Connolly, S.L.; Liu, R.T.; Stange, J.P.; Abramson, L.Y.; Alloy, L.B. It gets better: Future orientation buffers the development of hopelessness and depressive symptoms following emotional victimization during early adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 43, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddard, S.A.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Bauermeister, J.A. Thinking about the future as a way to succeed in the present: A longitudinal study of future orientation and violent behaviors among African American youth. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 48, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Voisin, D.R.; Jacobson, K.C. Community violence exposure and adolescent delinquency: Examining a spectrum of promotive factors. Youth Soc. 2013, 48, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotta, P.L.; Voisin, D.R. Testing three pathways to substance use and delinquency among low-income African American adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 75, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Espelage, D.L.; Holt, M.K. Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. J. Emot. Abuse 2001, 2, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylord-Harden, N.K.; Voisin, D.R. The Coping with Community Violence Scale; Unpublished Manuscript; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, S.; Paternoster, R.; Brame, R. Understanding the relationship between onset age and subsequent offending during adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, L.A.; Koeppel, M.D. Sex differences in the health risk behavior outcomes of childhood bullying victimization. Vict. Offenders 2016, 12, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazdowski, T.K.; Jaggi, L.; Borre, A.; Kliewer, W.L. Use of prescription drugs and future delinquency among adolescent offenders. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2015, 48, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walters, G.D.; Espelage, D.L. Mediating the bullying victimization-delinquency relationship with anger and cognitive impulsivity: A test of general strain and criminal lifestyle theories. J. Crim. Justice 2017, 53, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.P.; Molock, S.D.; Nieves-Lugo, K.; Zea, M.C. Anti-LGBT victimization, fear of violence at school, and suicide risk among adolescents. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2019, 6, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario, M.; Rotheram-Borus, M.J.; Reid, H. Gay-related stress and its correlates among gay and bisexual male adolescents of predominantly Black and Hispanic background. J. Community Psychol. 1996, 24, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnette, L.; Irvine, A.; Reyes, C.; Wilber, S. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth and the Juvenile Justice System. In Juvenile Justice: Advancing Research, Policy, and Practice; Sherman, F.T., Jacobs, F.H., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 156–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper, L.E.; Coleman, B.R.; Mustanski, B.S. Coping with LGBT and racial–ethnic-related stressors: A mixed-methods study of LGBT youth of color. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Reisner, S.L.; Menino, D.D.; Poteat, V.P.; Bogart, L.M.; Barnes, T.N.; Schuster, M.A. Stigma-based bullying interventions: A systematic review. Dev. Rev. 2018, 48, 178–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, N.; Tsao, B.; Hertz, M.; Davis, R.; Klevens, J. Connecting the Dots: An Overview of the Links Among Multiple Forms of Violence; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & Prevention Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2014.

- Cronholm, P.F.; Forke, C.M.; Wade, R.; Bair-Merritt, M.H.; Davis, M.; Harkins-Schwarz, M.; Pachter, L.M.; Fein, J.A. Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n = 541) | Non-Heterosexual/ Cisgender (n = 91) | Heterosexual (n = 450) | p a | Range | α | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M or % | SD | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | ||||

| Age | 15.85 | 1.37 | 15.77 | 1.31 | 15.87 | 1.38 | 0.535 | 12 to 18 | |

| Female | 0.55 | 0.84 | 0.49 | <0.001 | 1, 2 | ||||

| Ever using a drug (yes) | 0.6 | 0.77 | 0.57 | <0.001 | 0, 1 | ||||

| Ever involved in juvenile justice system (yes) | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 0, 1 | ||||

| Bullying victimization | 0.55 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 0.79 | 0.007 | 0 to 4 | 0.86 |

| Delinquent behavior | 1.65 | 3.64 | 2.57 | 4.8 | 1.47 | 3.33 | 0.08 | 0 to 20 | 0.88 |

| Motivation to move out of the community | 1.76 | 0.84 | 1.59 | 0.88 | 1.8 | 0.83 | 0.035 | 0 to 3 | 0.71 |

| Family structure | 0.08 | ||||||||

| Two-parent | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 1 | |||||

| Single-parent | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 2 | |||||

| Other | 0.1 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 3 | |||||

| Receiving public assistance | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.451 | 0, 1 | ||||

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 95% CI | p | IRR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Heterosexual (yes vs. no) | 0.72 | (0.44, 1.18) | 0.193 | 0.58 | (0.14, 2.34) | 0.443 | ||

| Age | 1.15 | (1, 1.31) | 0.044 | ** | 1.16 | (1.01, 1.33) | 0.03 | ** |

| Female (vs. male) | 0.62 | (0.43, 0.92) | 0.016 | ** | 0.66 | (0.45, 0.97) | 0.034 | ** |

| Ever using a drug (yes vs. no) | 2.36 | (1.61, 3.47) | <0.001 | *** | 2.6 | (1.76, 3.83) | <0.001 | *** |

| Ever involved in the juvenile justice system (yes vs. no) | 2.61 | (1.5, 4.53) | 0.001 | *** | 2.59 | (1.49, 4.5) | 0.001 | *** |

| Bullying victimization | 1.81 | (1.44, 2.28) | <0.001 | *** | 5.1 | (1.52, 17.12) | 0.008 | *** |

| Motivation to move out of the community | 0.74 | (0.58, 0.93) | 0.011 | ** | 0.75 | (0.37, 1.51) | 0.415 | |

| Family structure (two-parent) | ||||||||

| Single parent | 1.3 | (0.88, 1.92) | 0.185 | 1.3 | (0.89, 1.92) | 0.177 | ||

| Other | 1.18 | (0.62, 2.24) | 0.612 | 1.2 | (0.64, 2.25) | 0.573 | ||

| Receiving public assistance | 0.88 | (0.59, 1.34) | 0.559 | 0.84 | (0.55, 1.29) | 0.429 | ||

| Moderators | ||||||||

| Heterosexual × bullying | 0.39 | (0.09, 1.65) | 0.201 | |||||

| Heterosexual × Motivation to move out of the community | 1.13 | (0.53, 2.41) | 0.749 | |||||

| Bullying × Motivation to move out of the community | 0.46 | (0.23, 0.95) | 0.035 | ** | ||||

| Heterosexual × Bullying × Motivation to move out of the community | 2.06 | (0.92, 4.61) | 0.078 | * | ||||

| α | 3.07 | (2.47, 3.81) | <0.001 | *** | 2.94 | (2.36, 3.66) | <0.001 | *** |

| Pseudo-r2 | 0.06 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Log-likelihood | −771.67 | −767 | ||||||

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 95% CI | p | IRR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Age | 0.95 | (0.66, 1.36) | 0.769 | 0.96 | (0.68, 1.35) | 0.806 | ||

| Female (vs. male) | 0.39 | (0.14, 1.11) | 0.077 | * | 0.33 | (0.12, 0.92) | 0.033 | ** |

| Ever using a drug (yes vs. no) | 0.73 | (0.26, 2.01) | 0.54 | 0.79 | (0.29, 2.17) | 0.651 | ||

| Ever involved in the juvenile justice system (yes vs. no) | 4.61 | (1.66, 12.82) | 0.003 | *** | 4.23 | (1.6, 11.22) | 0.004 | *** |

| Bullying victimization | 2.09 | (1.32, 3.31) | 0.002 | *** | 7.31 | (2.48, 21.49) | <0.001 | *** |

| Motivation to move out of the community | 0.65 | (0.38, 1.11) | 0.112 | 1.13 | (0.6, 2.11) | 0.71 | ||

| Family structure (two-parent) | ||||||||

| Single parent | 1.09 | (0.43, 2.76) | 0.86 | 1.08 | (0.45, 2.57) | 0.863 | ||

| Other | 0.6 | (0.18, 2.07) | 0.423 | 0.7 | (0.22, 2.25) | 0.546 | ||

| Receiving public assistance | 0.52 | (0.21, 1.29) | 0.156 | 0.37 | (0.15, 0.91) | 0.031 | ** | |

| Moderators | ||||||||

| Bullying × Motivation to move out of the community | 0.43 | (0.23, 0.82) | 0.01 | *** | ||||

| α | 2.39 | (1.47, 3.9) | <0.001 | *** | 2.02 | (1.2, 3.38) | <0.001 | *** |

| Pseudo-r2 | 0.08 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Log-likelihood | −155 | 151.56 | ||||||

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 95% CI | p | IRR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Age | 1.22 | (1.05, 1.41) | 0.008 | *** | 1.22 | (1.06, 1.41) | 0.007 | *** |

| Female (vs. male) | 0.67 | (0.44, 1.02) | 0.061 | * | 0.68 | (0.45, 1.03) | 0.067 | * |

| Ever using a drug (yes vs. no) | 3.12 | (2.05, 4.74) | <0.001 | *** | 3.13 | (2.06, 4.76) | <0.001 | *** |

| Ever involved in the juvenile justice system (yes vs. no) | 2.54 | (1.33, 4.85) | 0.005 | *** | 2.5 | (1.3, 4.79) | 0.006 | *** |

| Bullying victimization | 1.93 | (1.46, 2.56) | <0.001 | *** | 2.24 | (1.04, 4.85) | 0.04 | ** |

| Motivation to move out of the community | 0.82 | (0.63, 1.06) | 0.136 | 0.85 | (0.63, 1.15) | 0.284 | ||

| Family structure (two-parent) | ||||||||

| Single parent | 1.18 | (0.77, 1.82) | 0.448 | 1.19 | (0.77, 1.84) | 0.427 | ||

| Other | 1.36 | (0.66, 2.83) | 0.408 | 1.37 | (0.66, 2.85) | 0.401 | ||

| Receiving public assistance | 1.02 | (0.63, 1.65) | 0.932 | 1.04 | (0.64, 1.68) | 0.886 | ||

| Moderators | ||||||||

| Bullying × Motivation to move out of the community | 0.93 | (0.64, 1.34) | 0.683 | |||||

| α | 2.98 | (2.33, 3.82) | <0.001 | *** | 2.98 | (2.33, 3.81) | <0.001 | *** |

| Pseudo-r2 | 0.07 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Log likelihood | −607.3 | −607.2 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, J.S.; Zhang, S.; Garthe, R.C.; Hicks, M.R.; deLara, E.W.; Voisin, D.R. Motivation to Move Out of the Community as a Moderator of Bullying Victimization and Delinquent Behavior: Comparing Non-Heterosexual/Cisgender and Heterosexual African American Adolescents in Chicago’s Southside. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12998. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412998

Hong JS, Zhang S, Garthe RC, Hicks MR, deLara EW, Voisin DR. Motivation to Move Out of the Community as a Moderator of Bullying Victimization and Delinquent Behavior: Comparing Non-Heterosexual/Cisgender and Heterosexual African American Adolescents in Chicago’s Southside. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):12998. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412998

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Jun Sung, Saijun Zhang, Rachel C. Garthe, Megan R. Hicks, Ellen W. deLara, and Dexter R. Voisin. 2021. "Motivation to Move Out of the Community as a Moderator of Bullying Victimization and Delinquent Behavior: Comparing Non-Heterosexual/Cisgender and Heterosexual African American Adolescents in Chicago’s Southside" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 12998. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412998

APA StyleHong, J. S., Zhang, S., Garthe, R. C., Hicks, M. R., deLara, E. W., & Voisin, D. R. (2021). Motivation to Move Out of the Community as a Moderator of Bullying Victimization and Delinquent Behavior: Comparing Non-Heterosexual/Cisgender and Heterosexual African American Adolescents in Chicago’s Southside. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 12998. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412998