“Coronavirus Changed the Rules on Everything”: Parent Perspectives on How the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced Family Routines, Relationships and Technology Use in Families with Infants

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment

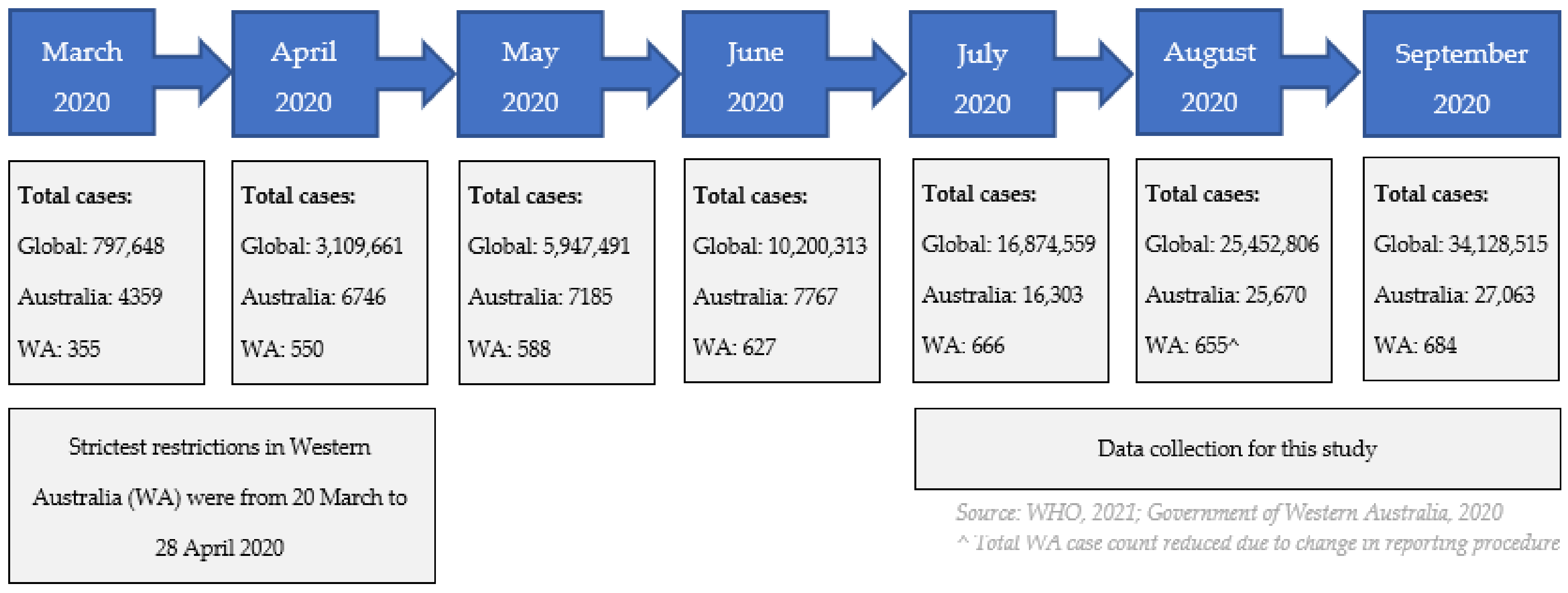

2.3. COVID-19 Context

2.4. Data Collection/Instrument

- (1).

- routines including work and childcare;

- (2).

- interactions and relationships;

- (3).

- device use by parents and infants.

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Influence of COVID-19 on Family Routines

3.3. Influence of COVID-19 on Family Relationships

3.4. Role of Mobile Touch Screen Device Use during COVID-19

3.4.1. Time Using Devices

3.4.2. Reasons for Using Devices

- Communication with family and friends, especially family interstate and overseas;

- Keeping children entertained while at home;

- Home-schooling and educational apps;

- Exercise such as yoga classes on YouTube;

- Online shopping;

- Working from home such as meetings via Zoom;

- Appointments such as physiotherapy;

- Reading news about the pandemic; and

- Searching for ideas for home activities to do with children.

3.4.3. Influence of Device Use

4. Discussion and Implications

5. Strengths and Limitations

5.1. Strengths

5.2. Limitations

6. Future Research

7. Conclusions

- Families described staying at home and stopping all external activities during the strictest pandemic-related restrictions in Western Australia.

- Three themes relating to family interactions and wellbeing were found due to the pandemic and associated restrictions: enhanced family relationships; prompted reflection on family schedules; and increased parental stress.

- Two themes related to family device use were found: enabled connections to be maintained; and source of disrupted interactions within the family unit.

- Overall, participants described more advantages than downsides of device use during COVID-19.

- Findings will be of value in providing useful information for families, health professionals and government advisors for use during future pandemic-related restrictions.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Announces COVID-19 Outbreak a Pandemic. World Health Organization. 2020. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Brooks, S.; Webster, R.; Smith, L.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rudin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, M.; Takeda, T.; Kumagai, K. A qualitative study of impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on lives in adults with attention deficit hyperactive disorder in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, E.E.; Presskreischer, R.; Han, H.; Barry, C.L. Psychological Distress and Loneliness Reported by US Adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA 2020, 324, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostacoli, L.; Cosma, S.; Bevilacqua, F.; Berchialla, P.; Bovetti, M.; Carosso, A.R.; Malandrone, F.; Carletto, S.; Benedetto, C. Psychosocial factors associated with postpartum psychological distress during the Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, F.; Sequerira, C.; Teixeria, L. Nurses’ mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, S.W.; Henkhaus, L.E.; Zickafoose, J.S.; Lovell, K.; Halvorson, A.; Loch, S.; Letterie, M.; Davis, M.M. Well-being of Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey. Pediatrics 2020, 146, 2020016824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalash, A.; Roushdy, T.; Essam, M.; Fathy, M.; Dawood, N.L.; Abushady, E.M.; Elrassas, H.; Helmi, A.; Hamid, E. Mental Health, Physical Activity, and Quality of Life in Parkinson’s Disease During COVID-19 Pandemic. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1097–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, A.K.; Sharma, N.; Samuel, A.J. Impact of Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) lockdown on physical activity and energy expenditure among physiotherapy professionals and students using web-based open E-survey sent through WhatsApp, Facebook and Instagram messengers. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 9, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.C.; Zieff, G.; Stanford, K.; Moore, J.B.; Kerr, Z.Y.; Hanson, E.K.; Gibbs, B.B.; Kline, C.E.; Stoner, L. COVID-19 impact on behaviors across the 24-h day in children and adolescents: Physical activity, sedentary behavior and sleep. Children 2020, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Boyland, E.; Chisholm, A.; Harrold, J.; Maloney, N.G.; Marty, L.; Mead, B.R.; Noonan, R.; Hardman, C.A. Obesity, eating behavior and physical activity during COVID-19 lockdown: A study of UK adults. Appetite 2021, 156, 104853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulic, D.; Blazevic, M.; Gilic, B.; Kvesic, I.; Zenic, N. Prospective Analysis of Levels and Correlates of Physical Activity during COVID-19 Pandemic and Imposed Rules of Social Distancing; Gender Specific Study among Adolescents from Southern Croatia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prime, H.; Wade, M.; Browne, D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss. Loss, Sadness and Depression (Vol.3); Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1980; pp. 1–472. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.; Blehar, M.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1979; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.; Klein, D. The Systems Framework. Family Theories, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 151–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P. The bioecological model of human development. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical Models of Human Development, 6th ed.; Lerner, R.M., Damon, W., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Straker, L.; Pollock, C. Optimizing the interaction of children with information and communication technologies. Ergonomics 2005, 48, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Straker, L.; Abbott, R.; Collins, R.; Campbell, A. Evidence-based guidelines for wise use of electronic games by children. Ergonomics 2014, 57, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.; Lanier, P.; Wong, P.Y.J. Mediating Effects of Parental Stress on Harsh Parenting and Parent-Child Relationship during Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in Singapore. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, B.; Lam, T.-H.; Lai, A.; Wang, M.; Ho, S.-Y. Perceived Benefits and Harms of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Well-Being and Their Sociodemographic Disparities in Hong Kong: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.Y.; Lockyer, B.; Dickerson, J.; Endacott, C.; Bridges, S.; McEachan, R.R.C.; Pickett, K.E.; Whalan, S.; Bear, N.L.; Silva, D.T.; et al. Comparison of Experiences in Two Birth Cohorts Comprising Young Families with Children under Four Years during the Initial COVID-19 Lockdown in Australia and the UK: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.A.; Zeanah, C.H.; Fox, N.A. How Early Experience Shapes Human Development: The Case of Psychosocial Deprivation. Neural Plast. 2019, 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theran, S.A.; Levendosky, A.A.; Bogat, A.G.; Huth-Bocks, A.C. Stability and change in mothers’ internal representations of their infants over time. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2005, 7, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, M.P.; O’Connor, E.E.; Barnes, S.P. Mother–child attachment styles and math and reading skills in middle childhood: The mediating role of children’s exploration and engagement. Early Child. Res. Q. 2016, 36, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Webb, H.J.; Pepping, C.A.; Swan, K.; Merlo, O.; Skinner, E.; Avdagic, E.; Dunbar, M. Review: Is parent-child attachment a correlate of children’s emotion regulation and coping? Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2017, 41, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Bunke, S.; Garwicz-Psouni, E. Attachment relationships and physical activity in adolescents: The mediation role of physical self-concept. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 22, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Huang, L.; Si, T.; Wang, N.Q.; Qu, M.; Zhang, X.Y. The role of only-child status in the psychological impact of COVID-19 on mental health of Chinese adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, M.M. Using tablets and apps to enhance emergent literacy skills in young children. Early Child. Res. Q. 2018, 42, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, A.W.; Wu, H.; Coryn, C.L. The effects of mobile phone use on academic performance: A meta-analysis. Comput. Educ. 2018, 127, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Coyne, S.M.; Fraser, A.M. Getting a High-Speed Family Connection: Associations Between Family Media Use and Family Connection. Fam. Relat. 2012, 61, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildare, C.A.; Middlemiss, W. Impact of parents mobile device use on parent-child interaction: A literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, R.; Zabatiero, J.; Zubrick, S.R.; Silva, D.; Straker, L. The association of mobile touch screen device use with parent-child attachment: A systematic review. Ergonomics 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamana, S.K.; Ezeugwu, V.; Chikuma, J.; Lefebvre, D.L.; Azad, M.B.; Moraes, T.J.; Subbarao, P.; Becker, A.B.; Turvey, S.E.; Sears, M.R.; et al. Screen-time is associated with inattention problems in preschoolers: Results from the CHILD birth cohort study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, A. Screen Time: What’s Happening in Our Homes? 2017. Available online: https://www.childhealthpoll.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ACHP-Poll7_Detailed-Report-June21.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Mangan, E.; Leavy, J.E.; Jancey, J. Mobile device use when caring for children 0-5 years: A naturalistic playground study. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2018, 29, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, V.A.; Starc, G.; Brandes, M.; Kaj, M.; Blagus, R.; Leskošek, B.; Suesse, T.; Dinya, E.; Guinhouya, B.C.; Zito, V.; et al. Physical activity, screen time and the COVID-19 school closures in Europe—An observational study in 10 countries. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drouin, M.; McDaniel, B.T.; Pater, J.; Toscos, T. How Parents and Their Children Used Social Media and Technology at the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Associations with Anxiety. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detnakarintra, K.; Trairatvorakul, P.; Pruksananonda, C.; Chonchaiya, W. Positive mother-child interactions and parenting styles were associated with lower screen time in early childhood. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. 12 June 2021. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 13 June 2021).

- Prime Minister of Australia. Border restrictions. Prime Minister of Australia. 2020a. Available online: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/border-restrictions (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Government of Western Australia. Changes to government school learning from Monday. Media Statements. 2020. Available online: https://www.mediastatements.wa.gov.au/Pages/McGowan/2020/03/Changes-to-government-school-learning-from-Monday.aspx (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Prime Minister of Australia. Update on coronavirus measures. Prime Minister of Australia. 2020b. Available online: https://www.pm.gov.au/media/update-coronavirus-measures-24-March-2020 (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Thorne, S.; Reimer Kirkham, S.; MacDonald-Emes, J. Interpretive description: A noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res. Nurs. Health 1997, 20, 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Condon, J. Maternal Postnatal Attachment Scale [Measurement Instrument]. 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2328/35291 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kompas, T.; Grafton, R.Q.; Che, T.N.; Chu, L.; Camac, J. Health and economic costs of early and delayed suppression and the unmitigated spread of COVID-19: The case of Australia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbiadini, A.; Baldissarri, C.; Durante, F.; Valtorta, R.R.; De Rosa, M.; Gallucci, M. Together Apart: The Mitigating Role of Digital Communication Technologies on Negative Affect During the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 554678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther-Bel, C.; Vilaregut, A.; Carratala, E.; Torras-Garat, S.; Pérez-Testor, C. A Mixed-method Study of Individual, Couple, and Parental Functioning During the State-regulated COVID-19 Lockdown in Spain. Fam. Process. 2020, 59, 1060–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Xiang, M.; Cheung, T.; Xiang, Y.-T. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal Children’s Hospital National Child Health Poll. COVID-19 pandemic: Effects on the lives of Australian children and families. Poll Number 18; The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne: Parkville, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Kuwahara, K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents’ lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kracht, C.; Katzmaryzk, P.T.; Stainano, A.E. Household chaos, family routines, and young child movement behaviours in the U.S. during the COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 860. [Google Scholar]

- Kolokotroni, O.; Mosquera, M.C.; Quattrocchi, A.; Heraclides, A.; Demetriou, C.; Philippou, E. Lifestyle habits of adults during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Cyprus: Evidence from a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.L.; Smith, D.; Caccavale, L.J.; Bean, M.K. Parents Are Stressed! Patterns of Parent Stress Across COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 626456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryluck, L.; Gold, W.L.; Robinson, S.; Pogorski, S.; Galea, S.; Styra, R. SARS Control and Psychological Effects of Quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccia, M. The relation between length of lockdown, numbers of infected people and deaths of COVID-19, and economic growth of countries: Lessons learned to cope with future pandemics similar to COVID-19 and to constrain the deterioration of the economic system. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, A.; Gorwood, P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chandola, T.; Kumari, M.; Booker, C.L.; Benzeval, M.J. The mental health impact of COVID-19 and lockdown-related stressors among adults in the UK. Psychol. Med. 2020, 20-12-07, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieh, C.; Budimir, S.; Humer, E.; Probst, T. Comparing Mental Health During the COVID-19 Lockdown and 6 Months After the Lockdown in Austria: A Longitudinal Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 625973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Participants | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changes to parent(s) work hours | Parent(s) had increased hours | 1, 11, 12, 21, 28 |

|

| Parent(s) had reduced hours | 9, 16, 18, 19, 23, 29 |

| |

| Parent(s) worked from home | 3, 12, 14, 18, 21, 22, 25, 27, 30 |

| |

| Parent(s) made redundant | 5, 13 |

| |

| Changes to childcare | No changes | 2, 7, 8, 10, 26 |

|

| Commenced daycare | 1 |

| |

| Abstained from daycare | 9, 11, 16, 20, 30 |

| |

| Changes to other activities | Stopped usual activities and stayed home during lockdown | 1, 3, 4, 13, 15, 24, 28 |

|

| Continued to reduce activities after lockdown restrictions eased | 3, 15, 28 |

|

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Participants | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced family relationships | Enhancing relationship between mother and infant | 4, 9, 16, 17, 18, 22, 23, 26 |

|

| Enhancing relationship between father and infant | 19, 28 |

| |

| Enhanced relationship within family unit | 2, 13, 16, 22, 23, 30 |

| |

| Prompted a reflection on family schedules | Reflection on family schedules | 6, 16, 22, 30 |

|

| Changes to family interactions | 2, 13, 21, 22, 23 |

| |

| Increased parental stress | Parental stress | 1, 5, 13, 20, 29 |

|

| Social isolation | 13, 15, 18, 20, 21, 24, 27 |

|

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Participants | Representative Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintained connections | Enabling communication with family | 3, 7, 10, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27 |

|

| Enabling activities to continue | 7, 13, 15, 17, 21, 22, 24, 25 |

| |

| Disrupted interactions within family unit | Increasing distraction from family | 4, 11, 20, 23 |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hood, R.; Zabatiero, J.; Silva, D.; Zubrick, S.R.; Straker, L. “Coronavirus Changed the Rules on Everything”: Parent Perspectives on How the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced Family Routines, Relationships and Technology Use in Families with Infants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312865

Hood R, Zabatiero J, Silva D, Zubrick SR, Straker L. “Coronavirus Changed the Rules on Everything”: Parent Perspectives on How the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced Family Routines, Relationships and Technology Use in Families with Infants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312865

Chicago/Turabian StyleHood, Rebecca, Juliana Zabatiero, Desiree Silva, Stephen R. Zubrick, and Leon Straker. 2021. "“Coronavirus Changed the Rules on Everything”: Parent Perspectives on How the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced Family Routines, Relationships and Technology Use in Families with Infants" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312865

APA StyleHood, R., Zabatiero, J., Silva, D., Zubrick, S. R., & Straker, L. (2021). “Coronavirus Changed the Rules on Everything”: Parent Perspectives on How the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced Family Routines, Relationships and Technology Use in Families with Infants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312865