Factors Associated with Unfavourable Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Tuberculosis: A 16-Year Cohort Study (2005–2020), Republic of Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.2.1. General Setting

2.2.2. TB Control

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Source of Data, Data Collection and Data Variables

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population and Their Overall Treatment Outcomes

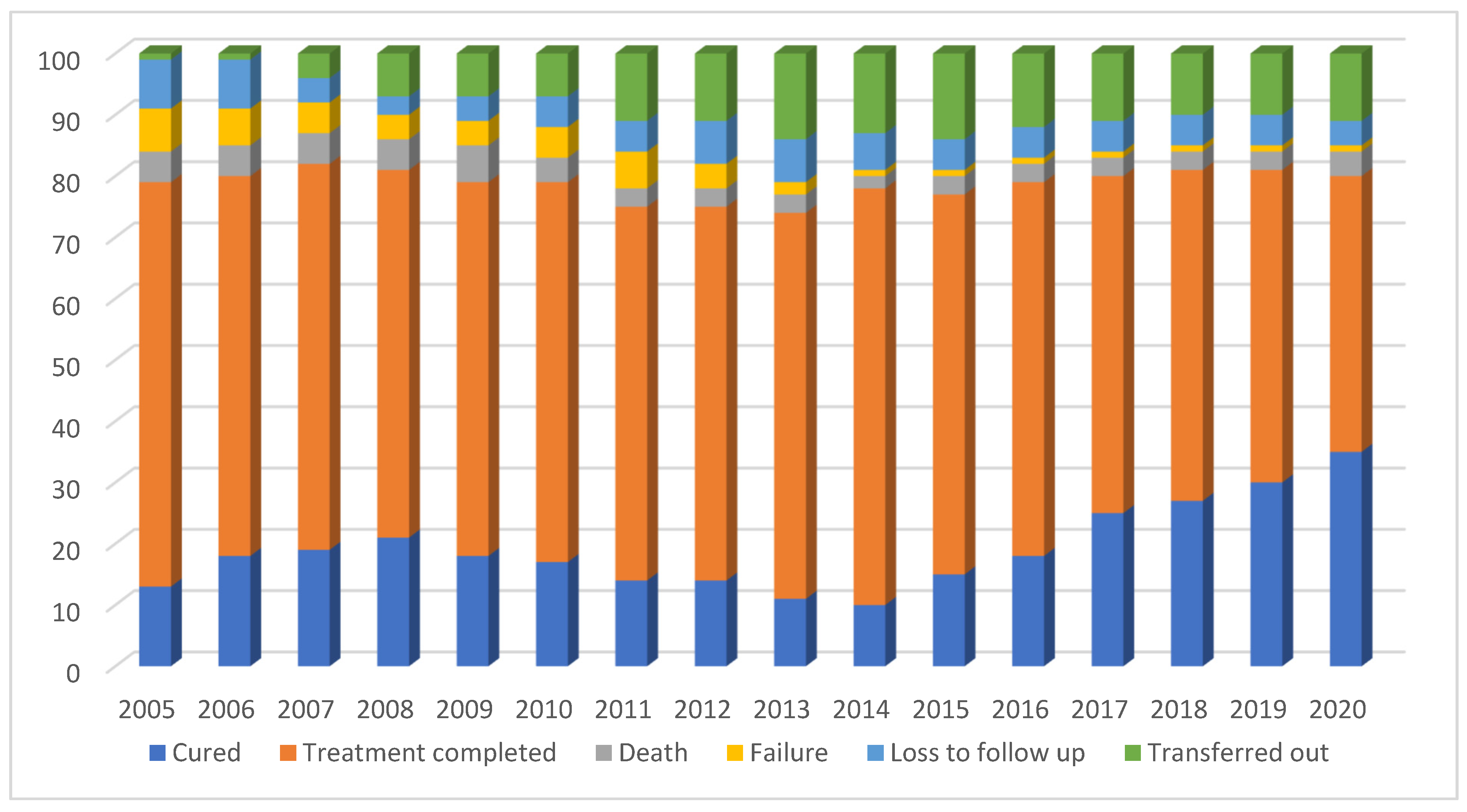

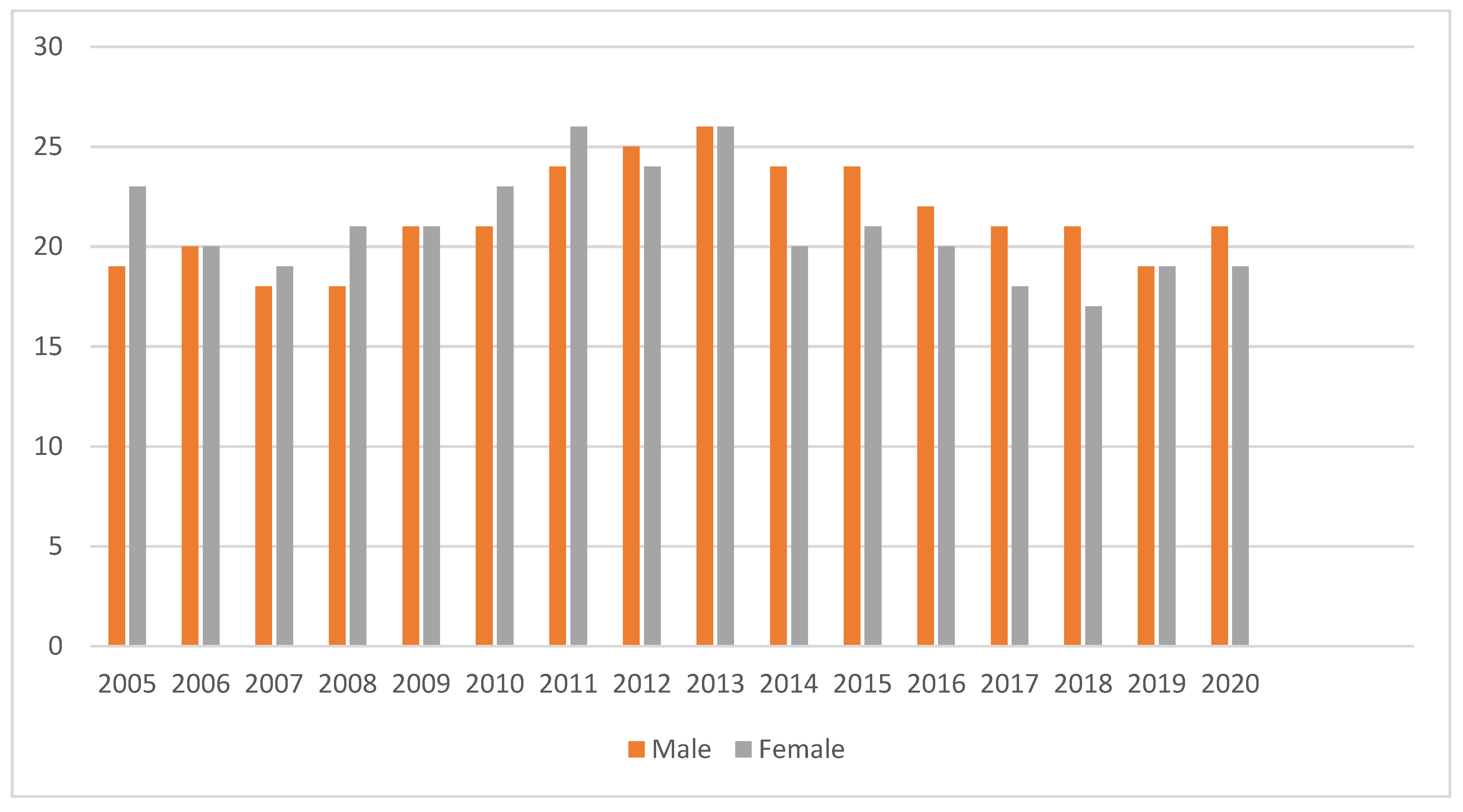

3.2. Trends in Annual Treatment Outcomes between 2005 and 2020

3.3. Risk Factors for Unfavourable Outcomes, Death, Failure and Loss to Follow-Up

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

References

- World Health Organization (Global Tuberculosis Programme). Global Tuberculosis Report 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 9789240013131. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/336069 (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Floyd, K.; Falzon, D.; Getahun, H.; Kanchar, A.; Mirzayev, F.; Raviglione, M.; Timimi, H.; Weyer, K.; Zignol, M. Use of High Burden Country Lists for TB by WHO in the Post-2015 Era; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Small, I.; Van Der Meer, J.; Upshur, R.E.G. Acting on an environmental health disaster: The case of the Aral Sea. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadoev, J.; Asadov, D.; Tillashaykhov, M.; Tayler-Smith, K.; Isaakidis, P.; Dadu, A.; De Colombani, P.; Hinderaker, S.G.; Parpieva, N.; Ulmasova, D.; et al. Factors Associated with Unfavorable Treatment Outcomes in New and Previously Treated TB Patients in Uzbekistan: A Five Year Countrywide Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmasova, D.J.; Uzakova, G.; Tillyashayhov, M.N.; Turaev, L.; Van Gemert, W.; Hoffmann, H.; Zignol, M.; Kremer, K.; Gombogaram, T.; Gadoev, J.; et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Uzbekistan: Results of a nationwide survey, 2010 to 2011. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics. Available online: https://stat.uz/en/o?cial-statistics/demography (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Ahmedov, M.; Azimov, R.; Mutalova, Z.; Huseynov, S.; Tsoyi, E.; Rechel, B. Uzbekistan: Health Systems in Transition. Health Syst. Transit. 2014, 16, 5. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/270370/Uzbekistan-HiT-web.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- The Government Portal of the Republic of Karakalpakstan. Available online: http://www.karakalpakstan.uz/en/page/show/4 (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Sakiev, K.Z. On evaluation of public health state in Aral Sea. Meditsina Tr. Promyshlennaia Ekol. 2014, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Massavirov, S.; Akopyan, K.; Abdugapparov, F.; Ciobanu, A.; Hovhanessyan, A.; Khodjaeva, M.; Gadoev, J.; Parpieva, N. Risk Factors for Unfavorable Treatment Outcomes among the Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Tuberculosis Population in Tashkent City, Uzbekistan: 2013–2017. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuldashev, S.; Parpieva, N.; Alimov, S.; Turaev, L.; Safaev, K.; Dumchev, K.; Gadoev, J.; Korotych, O.; Harries, A.D. Scaling up molecular diagnostic tests for drug-resistant tuberculosis in Uzbekistan from 2012–2019: Are we on the right track? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubnikov, A.; Hovhannesyan, A.; Akopyan, K.; Ciobanu, A.; Sadirova, D.; Kalandarova, L.; Parpieva, N.; Gadoev, J. Effectiveness and Safety of a Shorter Treatment Regimen in a Setting with a High Burden of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaev, K.; Parpieva, N.; Liverko, I.; Yuldashev, S.; Dumchev, K.; Gadoev, J.; Korotych, O.; Harries, A. Trends, Characteristics and Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Uzbekistan: 2013–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmanova, R.; Parpieva, N.; Davtyan, H.; Denisiuk, O.; Gadoev, J.; Alaverdyan, S.; Dumchev, K.; Liverko, I.; Abdusamatova, B. Treatment compliance of multidrug resistant tuberculosis in Uzbekistan: Does practice follow policy? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hest, R.; Ködmön, C.; Verver, S.; Erkens, C.G.; Straetemans, M.; Manissero, D.; de Vries, G. Tuberculosis treatment outcome monitoring in European Union countries: Systematic review. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 41, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, K.; Rodriguez, C.A.; Berhanu, R.; Ismail, N.; Mvusi, L.; Long, L.; Evans, D. Treatment outcomes among children, adolescents, and adults on treatment for tuberculosis in two metropolitan municipalities in Gauteng Province, South Africa. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amnuaiphon, W.; Anuwatnonthakate, A.; Nuyongphak, P.; Sinthuwatanawibool, C.; Rujiwongsakorn, S.; Nakara, P.; Komsakorn, S.; Wattanaamornkiet, W.; Moolphate, S.; Chiengsorn, N.; et al. Factors associated with death among HIV-uninfected TB patients in Thailand, 2004–2006. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2009, 14, 1338–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chung-Delgado, K.; Revilla-Montag, A.; Guillen-Bravo, S.; Velez-Segovia, E.; Soria-Montoya, A.; Nuñez-Garbin, A.; Caso, W.G.S.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A. Factors Associated with Anti-Tuberculosis Medication Adverse Effects: A Case-Control Study in Lima, Peru. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seid, M.A.; Ayalew, M.B.; Muche, E.A.; Gebreyohannes, E.A.; Abegaz, T.M. Drug-susceptible tuberculosis treatment success and associated factors in Ethiopia from 2005 to 2017: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadykova, L.; Abramavičius, S.; Maimakov, T.; Berikova, E.; Kurakbayev, K.; Carr, N.T.; Padaiga, Ž.; Naudžiūnas, A.; Stankevičius, E. A retrospective analysis of treatment outcomes of drug-susceptible TB in Kazakhstan, 2013–2016. Medicine 2019, 98, e16071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Wang, J.-Y.; Lin, H.-C.; Lin, P.-Y.; Chang, J.-H.; Suk, C.-W.; Lee, L.-N.; Lan, C.-C.; Bai, K.-J. Treatment delay and fatal outcomes of pulmonary tuberculosis in advanced age: A retrospective nationwide cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoheisel, G.; Hagert-Winkler, A.; Winkler, J.; Kahn, T.; Rodloff, A.C.; Wirtz, H.; Gillissen, A. Tuberkulose der Lunge und Pleura im Alter*. Med. Klin. 2009, 104, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbini, E.; Greco, A.; Estrada, S.; Cisneros, M.; Colombo, C.; Beltrame, S.; Boncompain, C.; Genero, S. Risk factors associated with tuberculosis mortality in adults in six provinces of Argentina. Medicina (B Aires) 2017, 77, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylski, G.; Dąbrowska, A.; Pilaczyńska-Cemel, M.; Krawiecka, D. Unemployment in TB patients—Ten-year observation at regional center of pulmonology in bydgoszcz, Poland. Med. Sci. Monit. 2014, 20, 2125–2131. [Google Scholar]

- Jagodziński, J.; Zielonka, T.M.; Błachnio, M. Socio-economic status and duration of TB symptoms in males treated at the Mazovian Treatment Centre of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases in Otwock. Pneumonol. Alergol. Pol. 2012, 80, 533–540. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, P.K.; Arguin, P.M.; Kiryanova, H.; Kondroshova, N.V.; Khorosheva, T.M.; Laserson, K. Risk factors for death during tuberculosis treatment in Orel, Russia. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2004, 8, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahlburg, D.A.; Stop TB Initiative & Ministerial Conference on Tuberculosis and Sustainable Development (2000: Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The Economic Impacts of Tuberculosis. World Health Organization. 2000. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66238 (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control: WHO Report 2011. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44728 (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Cardoso, M.A.; Brasil, P.E.; Schmaltz, C.A.S.; Sant’Anna, F.M.; Rolla, V.C. Tuberculosis Treatment Outcomes and Factors Associated with Each of Them in a Cohort Followed Up between 2010 and 2014. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatechompol, S.; Kawkitinarong, K.; Suwanpimolkul, G.; Kateruttanakul, P.; Manosuthi, W.; Sophonphan, J.; Ubolyam, S.; Kerr, S.J.; Avihingsanon, A.; Ruxrungtham, K. Treatment outcomes and factors associated with mortality among individuals with both TB and HIV in the antiretroviral era in Thailand. J. Virus Erad. 2019, 5, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chem, E.D.; Van Hout, M.C.; Hope, V. Treatment outcomes and antiretroviral uptake in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV co-infected patients in Sub Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noertjojo, K.; Tam, C.M.; Chan, S.L.; Chan-Yeung, M.M.W. Extra-pulmonary and pulmonary tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2002, 6, 879–886. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.B.; Meghji, J.; Squire, S.B. A systematic review of clinical outcomes on the WHO Category II retreatment regimen for tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2018, 22, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitikov, E.; Vyazovaya, A.; Malakhova, M.; Guliaev, A.; Bespyatykh, J.; Proshina, E.; Pasechnik, O.; Mokrousov, I. Simple Assay for Detection of the Central Asia Outbreak Clade of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing Genotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, D.; Martinez, L.; Lu, P.; Zhu, L.; Lu, W.; Wang, J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype strains and unfavourable treatment outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 26, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piubello, A.; Harouna, S.H.; Souleymane, M.B.; Boukary, I.; Morou, S.; Daouda, M.; Hanki, Y.; Van Deun, A. High cure rate with standardised short-course multi drug resistant tuberculosis treatment in Niger: No relapses. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2014, 18, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trébucq, A.; Schwoebel, V.; Kashongwe, Z.; Bakayoko, A.; Kuaban, C.; Noeske, J.; Hassane, S.; Souleymane, B.; Piubello, A.; Ciza, F.; et al. Treatment outcome with a short multidrug-resistant tuberculosis regimen in nine African countries. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2018, 22, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 35,122 |

| Age in years | |

| Children (0–14) | 2339 (7) |

| Adolescent (15–18) | 2038 (6) |

| Adults (19–55) | 24,394 (69) |

| Elderly (above 55) | 6351 (18) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 18,032 (51) |

| Female | 17,090 (49) |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban | 9289 (26) |

| Rural | 19,774 (56) |

| Missing data | 6059 (17) |

| Geographic distribution | |

| Central part | 18,572 (53) |

| North-West | 9060 (26) |

| South-East | 7490 (21) |

| Social characteristics | |

| Worker | 1605 (5) |

| Employee | 1440 (4) |

| Pupil | 2572 (7) |

| Disabled | 819 (2) |

| Preschool age, kindergarten | 125 (<1) |

| Preschool not attending kindergarten | 671 (2) |

| Pensioner | 3577 (10) |

| Unemployed | 15,409 (44) |

| Missing data | 8904 (25) |

| HIV status | |

| HIV positive | 19 (<1) |

| HIV negative | 26,373 (75) |

| Missing data | 8730 (24) |

| Past prisoner | |

| No | 2582 (7) |

| Yes | 9 (<1) |

| Missing data | 32,531 (92) |

| Contact with TB patient | |

| Yes | 23,417 (67) |

| No | 1915 (5) |

| Missing data | 9790 (28) |

| TB type | |

| PTB (Pulmonary TB) | 29,130 (83) |

| EPTB (Extrapulmonary TB) | 5992 (17) |

| TB treatment category | |

| I category (2(3)HRZE(S)/4 H3R3) a | 27,465 (79) |

| II category (2HRZES/1(2)HRZE/5 H3R3E3) b | 7497 (21) |

| III category (2HRZ/4 H3R3) c | 160 (<1) |

| Treatment Outcomes | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Favourable outcomes | 27,682 (79) |

| Cured | 6193 (18) |

| Treatment completed | 21,489 (61) |

| Unfavourable outcomes | 7440 (21) |

| Died | 1419 (4) |

| Failure | 1220 (3) |

| Loss to follow up | 1948 (6) |

| Transfer out | 2853 (8) |

| Variable | n | Unfavourable Treatment Outcome | Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | RR | 95%CI | p Value | aRR | 95%CI | p Value | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| Children (0–14) | 2339 | 186 | 8.0 | 0.36 | (0.32–0.42) | <0.001 | 0.55 | (0.43–0.69) | <0.001 |

| Adolescent (15–18) | 2038 | 394 | 19.3 | 0.88 | (0.81–0.97) | <0.009 | 0.99 | (0.85–1.1) | <0.838 |

| Adults (19–55) | 24,394 | 5331 | 21.9 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Elderly (above 55) | 6351 | 1529 | 24.1 | 1.1 | (1–1.16) | <0.001 | 1.27 | (1.12–1.44) | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 18,032 | 3816 | 21.2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 17,090 | 3624 | 21.2 | 1 | (0.96–1.04) | 0.921 | 1.00 | (0.95–1.05) | 0.882 |

| Place of residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 9289 | 2191 | 23.6 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Rural | 19,774 | 3466 | 17.5 | 0.74 | (0.71–0.78) | <0.001 | 0.88 | (0.84–0.93) | <0.001 |

| Geographic variations | |||||||||

| South-East | 7490 | 1077 | 14.4 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| North-West | 9060 | 1722 | 19.0 | 1.32 | (1.23–1.42) | <0.001 | 1.29 | (1.17–1.41) | <0.001 |

| Central part | 18,572 | 4641 | 25.0 | 1.74 | (1.64–1.85) | <0.001 | 1.68 | (1.55–1.83) | <0.001 |

| Social characteristics | |||||||||

| Worker | 1605 | 217 | 13.5 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Employee | 1440 | 203 | 14.1 | 1.04 | (0.87–1.25) | 0.645 | 1.00 | (0.84–1.20) | 0.965 |

| Pupil | 2572 | 297 | 11.5 | 0.85 | (0.73–1.03) | 0.059 | 1.13 | (0.92–1.40) | 0.245 |

| Disabled | 819 | 185 | 22.6 | 1.67 | (1.40–2.00) | 0.000 | 1.49 | (1.25–1.78) | <0.001 |

| Preschool age, kindergarten | 125 | 9 | 7.2 | 0.53 | (0.28–1.01) | 0.054 | 0.84 | (0.44–1.61) | 0.598 |

| Preschool not attending kindergarten | 671 | 44 | 6.6 | 0.49 | (0.36–0.66) | 0.000 | 0.90 | (0.61–1.32) | 0.581 |

| Pensioner | 3577 | 779 | 21.8 | 1.61 | (1.40–1.85) | 0.000 | 1.28 | (1.07–1.53) | 0.006 |

| Unemployed | 15,409 | 2981 | 19.3 | 1.43 | (1.26–1.62) | 0.000 | 1.38 | (1.22–1.57) | <0.001 |

| HIV status | |||||||||

| HIV positive | 19 | 10 | 52.6 | 2.90 | (1.89–4.45) | <0.001 | 3.16 | (1.96–5.09) | <0.001 |

| HIV negative | 26,373 | 4782 | 18.1 | 1.00 | 1 | ||||

| Contact with TB patient | |||||||||

| No | 23,417 | 4068 | 17.4 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1915 | 391 | 20.4 | 1.18 | (1.07–1.29) | 0.001 | 1.20 | (1.09–1.31) | 0.011 |

| TB type | |||||||||

| PTB(Pulmonary TB) | 29,130 | 6712 | 23.0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| EPTB (Extrapulmonary TB) | 5992 | 728 | 12.1 | 0.53 | (0.49–0.57) | <0.001 | 0.67 | (0.62–0.72) | <0.001 |

| TB treatment category | |||||||||

| I category | 27,465 | 5018 | 18.3 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| II category | 7497 | 2417 | 32.2 | 1.76 | (1.69–1.84) | <0.001 | 1.22 | (1.05–1.43) | 0.011 |

| III category | 160 | 5 | 3.1 | 0.17 | (0.07–0.41) | <0.001 | 0.26 | (0.11–0.62) | 0.002 |

| Variable | n | Deaths | Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | RR | 95%CI | p Value | aRR | 95%CI | p Value | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| Children (0–14) | 2339 | 26 | 1.1 | 0.33 | (0.22–0.48) | <0.001 | 0.48 | (0.23–1.02) | 0.056 |

| Adolescent (15–18) | 2038 | 40 | 2.0 | 0.58 | (0.42–0.79) | 0.001 | 0.69 | (0.38–1.25) | 0.225 |

| Adults (19–55) | 24,394 | 826 | 3.4 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Elderly (above 56) | 6351 | 527 | 8.3 | 2.45 | (2.20–2.72) | <0.001 | 2.35 | (1.82–3.02) | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 18,032 | 692 | 3.8 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 17,090 | 727 | 4.3 | 1.11 | (1.00–1.23) | 0.048 | 1.05 | (0.91–1.21) | 0.522 |

| Place of residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 9289 | 362 | 3.9 | 1 | |||||

| Rural | 19,774 | 727 | 3.7 | 0.94 | (0.83–1.07) | 0.356 | |||

| Geographic variations | |||||||||

| South-East | 7490 | 281 | 3.8 | 1 | |||||

| North-West | 9060 | 348 | 3.8 | 1.02 | (0.88–1.19) | 0.765 | |||

| Central | 18,572 | 790 | 4.3 | 1.13 | (0.99–1.30) | 0.065 | |||

| Social characteristics | |||||||||

| Worker | 1605 | 32 | 2.0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Employee | 1440 | 21 | 1.5 | 0.73 | (0.42–1.26) | 0.261 | 0.66 | (0.38–1.17) | 0.161 |

| Pupil | 2572 | 22 | 0.9 | 0.43 | (0.25–0.74) | 0.002 | 0.80 | (0.38–1.69) | 0.565 |

| Disabled | 819 | 61 | 7.4 | 3.74 | (2.46–5.68) | <0.001 | 2.93 | (1.91–4.48) | <0.001 |

| Preschool age, kindergarten | 125 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.40 | (0.056–2.91) | 0.367 | 0.86 | (0.10–7.13) | 0.887 |

| Preschool not attending kindergarten | 671 | 6 | 0.9 | 0.45 | (0.19–1.07) | 0.070 | 1.08 | (0.37–3.09) | 0.892 |

| Pensioner | 3577 | 272 | 7.6 | 3.81 | (2.66–5.48) | <0.001 | 1.76 | (1.15–2.69) | 0.009 |

| Unemployed | 15,409 | 381 | 2.5 | 1.24 | (0.87–1.78) | 0.237 | 1.11 | (0.77–1.58) | 0.578 |

| HIV status | |||||||||

| HIV positive | 19 | 5 | 26.3 | 8.40 | (3.95–17.88) | <0.001 | 9.95 | (4.76–20.80) | <0.001 |

| HIV negative | 26,373 | 826 | 3.1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Contact with TB patient | |||||||||

| No | 23,417 | 665 | 2.8 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 1915 | 50 | 2.6 | 0.92 | (0.69–1.22) | 0.561 | |||

| TB type | |||||||||

| PTB(Pulmonary TB) | 29,130 | 1296 | 4.4 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| EPTB (Extrapulmonary TB) | 5992 | 123 | 2.1 | 0.46 | (0.38–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.72 | (0.58–0.90) | <0.001 |

| TB treatment category | |||||||||

| I category | 27,465 | 800 | 2.9 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| II category | 7497 | 616 | 8.2 | 2.82 | (2.55–3.12) | <0.001 | 3.27 | (2.63–4.07) | <0.001 |

| III category | 160 | 3 | 1.9 | 0.64 | (0.21–1.98) | 0.442 | 1.27 | (0.43–3.79) | 0.669 |

| Variable | n | Failure | Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | RR | 95%CI | p Value | aRR | 95%CI | p Value | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| Children (0–14) | 2339 | 29 | 1.2 | 0.32 | (0.22–0.46) | <0.001 | 0.76 | (0.43–1.34) | 0.343 |

| Adolescent (15–18) | 2038 | 115 | 5.6 | 1.44 | (1.20–1.75) | <0.001 | 1.55 | (1.12–2.15) | 0.008 |

| Adults (19–55) | 24,394 | 952 | 3.9 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Elderly (above 56) | 6351 | 124 | 2.0 | 0.50 | (0.42–0.60) | 0.027 | 0.67 | (0.44–1.03) | 0.069 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 18,032 | 541 | 3.0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 17,090 | 679 | 4.0 | 1.32 | (1.19–4.48) | <0.001 | 1.29 | (1.11–1.49) | 0.001 |

| Place of residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 9289 | 331 | 3.6 | 1 | |||||

| Rural | 19,774 | 711 | 3.6 | 1.01 | (0.89–1.15) | 0.890 | |||

| Geographic variations | |||||||||

| South-East | 7490 | 234 | 3.1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| North-West | 9060 | 380 | 4.2 | 1.34 | (1.14–1.58) | <0.001 | 1.21 | (0.98–1.49) | 0.069 |

| Central | 18,572 | 606 | 3.3 | 1.04 | (0.90–1.21) | 0.566 | 0.93 | (0.77–1.12) | 0.443 |

| Social characteristics | |||||||||

| Worker | 1605 | 45 | 2.8 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Employee | 1440 | 48 | 3.3 | 1.19 | (0.79–1.77) | 0.397 | 1.07 | (0.72–1.60) | 0.729 |

| Pupil | 2572 | 70 | 2.7 | 0.97 | (0.67–1.4) | 0.875 | 0.87 | (0.53–1.41) | 0.571 |

| Disabled | 819 | 25 | 3.1 | 1.09 | (0.67–1.76) | 0.729 | 1.05 | (0.65–1.71) | 0.834 |

| Preschool age, kindergarten | 125 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.29 | (0.03–2.05) | 0.213 | 0.43 | (0.06–3.21) | 0.409 |

| Preschool not attending kindergarten | 671 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.05 | (0–0.38) | 0.004 | 0.10 | (0.01–0.78) | 0.028 |

| Pensioner | 3577 | 78 | 2.2 | 0.78 | (0.54–1.11) | 0.174 | 0.97 | (0.58–1.62) | 0.898 |

| Unemployed | 15,409 | 519 | 3.4 | 1.20 | (0.88–1.62) | 0.231 | 1.05 | (0.77–1.42) | 0.772 |

| HIV status | |||||||||

| HIV positive | 19 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | (0.00–0.00) | <0.001 | 0.00 | (0.00–0.00) | <0.001 |

| HIV negative | 26,373 | 789 | 3.0 | 1 | |||||

| Contact with TB patient | |||||||||

| No | 23,417 | 630 | 2.7 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1915 | 105 | 5.5 | 2.04 | (1.67–2.49) | <0.001 | 1.94 | (1.58–2.39) | <0.001 |

| TB type | |||||||||

| PTB (Pulmonary TB) | 29,130 | 1200 | 4.1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| EPTB (Extrapulmonary TB) | 5992 | 20 | 0.3 | 0.08 | (0.05–0.13) | <0.001 | 0.10 | (0.06–0.17) | <0.001 |

| TB treatment category | |||||||||

| I category | 27,465 | 730 | 2.7 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| II category | 7497 | 490 | 6.5 | 2.46 | 1.34 | (0.87–2.07) | 0.179 | ||

| III category | 160 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | (0.00–0.00) | <0.001 | 0.00 | (0.00–0.00) | <0.001 |

| Variable | n | Loss to Follow Up | Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | RR | 95%CI | p Value | aRR | 95%CI | p Value | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| Children (0–14) | 2339 | 84 | 3.6 | 0.63 | (0.51–0.78) | <0.001 | 0.97 | (0.64–1.47) | 0.879 |

| Adolescent (15–18) | 2038 | 74 | 3.6 | 0.63 | (0.50–0.80) | 0.944 | 0.86 | (0.63–1.17) | 0.331 |

| Adults (19–55) | 24,394 | 1397 | 5.7 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Elderly (above 56) | 6351 | 393 | 6.2 | 1.08 | (0.97–1.20) | <0.001 | 1.16 | (0.91–1.47) | 0.237 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 18,032 | 1092 | 6.1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 17,090 | 856 | 5.0 | 0.83 | (0.75–0.90) | <0.001 | 0.81 | (0.72–0.90) | <0.001 |

| Place of residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 9289 | 568 | 6.1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Rural | 19,774 | 881 | 4.5 | 0.73 | (0.66–0.81) | <0.001 | 0.88 | (0.78–0.99) | 0.036 |

| Geographic variations | |||||||||

| South-East | 7490 | 279 | 3.7 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| North-West | 9060 | 430 | 4.7 | 1.01 | (0.8–1.27) | 0.924 | 1.17 | (0.96–1.43) | 0.112 |

| Central | 18,572 | 1239 | 6.7 | 0.89 | (0.76–1.02) | 0.116 | 1.78 | (1.50–2.11) | <0.001 |

| Social characteristics | |||||||||

| Worker | 1605 | 42 | 2.6 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Employee | 1440 | 32 | 2.2 | 0.85 | (0.53–1.33) | 0.481 | 0.87 | (0.55–1.36) | 0.535 |

| Pupil | 2572 | 71 | 2.8 | 1.05 | (0.72–1.53) | 0.781 | 1.16 | (0.73–1.86) | 0.527 |

| Disabled | 819 | 43 | 5.3 | 2.01 | (1.32–3.04) | 0.001 | 1.82 | (0.20–2.76) | 0.005 |

| Preschool age, kindergarten | 125 | 3 | 2.4 | 0.92 | (0.28–2.91) | 0.884 | 0.89 | (0.27–2.91) | 0.847 |

| Preschool not attending kindergarten | 671 | 32 | 4.8 | 1.82 | (1.16–2.86) | 0.009 | 1.76 | (0.96–3.22) | 0.067 |

| Pensioner | 3577 | 168 | 4.7 | 1.79 | (1.28–2.50) | 0.001 | 1.67 | (1.13–2.46) | 0.010 |

| Unemployed | 15,409 | 786 | 5.1 | 1.95 | (1.43–2.64) | <0.001 | 1.95 | (1.43–2.65) | <0.001 |

| HIV status | |||||||||

| HIV positive | 19 | 2 | 10.5 | 1.40 | (0.64–8.90) | 0.192 | |||

| HIV negative | 26,373 | 1159 | 4.4 | 1 | |||||

| Contact with TB patient | |||||||||

| No | 23,417 | 1031 | 4.4 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 1915 | 73 | 3.8 | 0.87 | (0.69–1.09) | 0.225 | |||

| TB type | |||||||||

| PTB (Pulmonary TB) | 29,130 | 1623 | 5.6 | 1 | |||||

| EPTB (Extrapulmonary TB) | 5992 | 325 | 5.4 | 0.97 | (0.87–1.09) | 0.649 | |||

| TB treatment category | |||||||||

| I category | 27,465 | 1282 | 4.7 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| II category | 7497 | 664 | 8.9 | 1.90 | (1.73–2.08) | <0.001 | 1.60 | (1.32–1.95) | <0.001 |

| III category | 160 | 2 | 1.3 | 0.27 | (0.07–1.06) | 0.061 | 0.34 | (0.08–1.34) | 0.122 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gadoev, J.; Asadov, D.; Harries, A.D.; Kumar, A.M.V.; Boeree, M.J.; Hovhannesyan, A.; Kuppens, L.; Yedilbayev, A.; Korotych, O.; Hamraev, A.; et al. Factors Associated with Unfavourable Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Tuberculosis: A 16-Year Cohort Study (2005–2020), Republic of Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312827

Gadoev J, Asadov D, Harries AD, Kumar AMV, Boeree MJ, Hovhannesyan A, Kuppens L, Yedilbayev A, Korotych O, Hamraev A, et al. Factors Associated with Unfavourable Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Tuberculosis: A 16-Year Cohort Study (2005–2020), Republic of Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312827

Chicago/Turabian StyleGadoev, Jamshid, Damin Asadov, Anthony D. Harries, Ajay M. V. Kumar, Martin Johan Boeree, Araksya Hovhannesyan, Lianne Kuppens, Askar Yedilbayev, Oleksandr Korotych, Atadjan Hamraev, and et al. 2021. "Factors Associated with Unfavourable Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Tuberculosis: A 16-Year Cohort Study (2005–2020), Republic of Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312827

APA StyleGadoev, J., Asadov, D., Harries, A. D., Kumar, A. M. V., Boeree, M. J., Hovhannesyan, A., Kuppens, L., Yedilbayev, A., Korotych, O., Hamraev, A., Kudaybergenov, K., Abdusamatova, B., Khudanov, B., & Dara, M. (2021). Factors Associated with Unfavourable Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Tuberculosis: A 16-Year Cohort Study (2005–2020), Republic of Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312827