Speak like a Native English Speaker or Be Judged: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

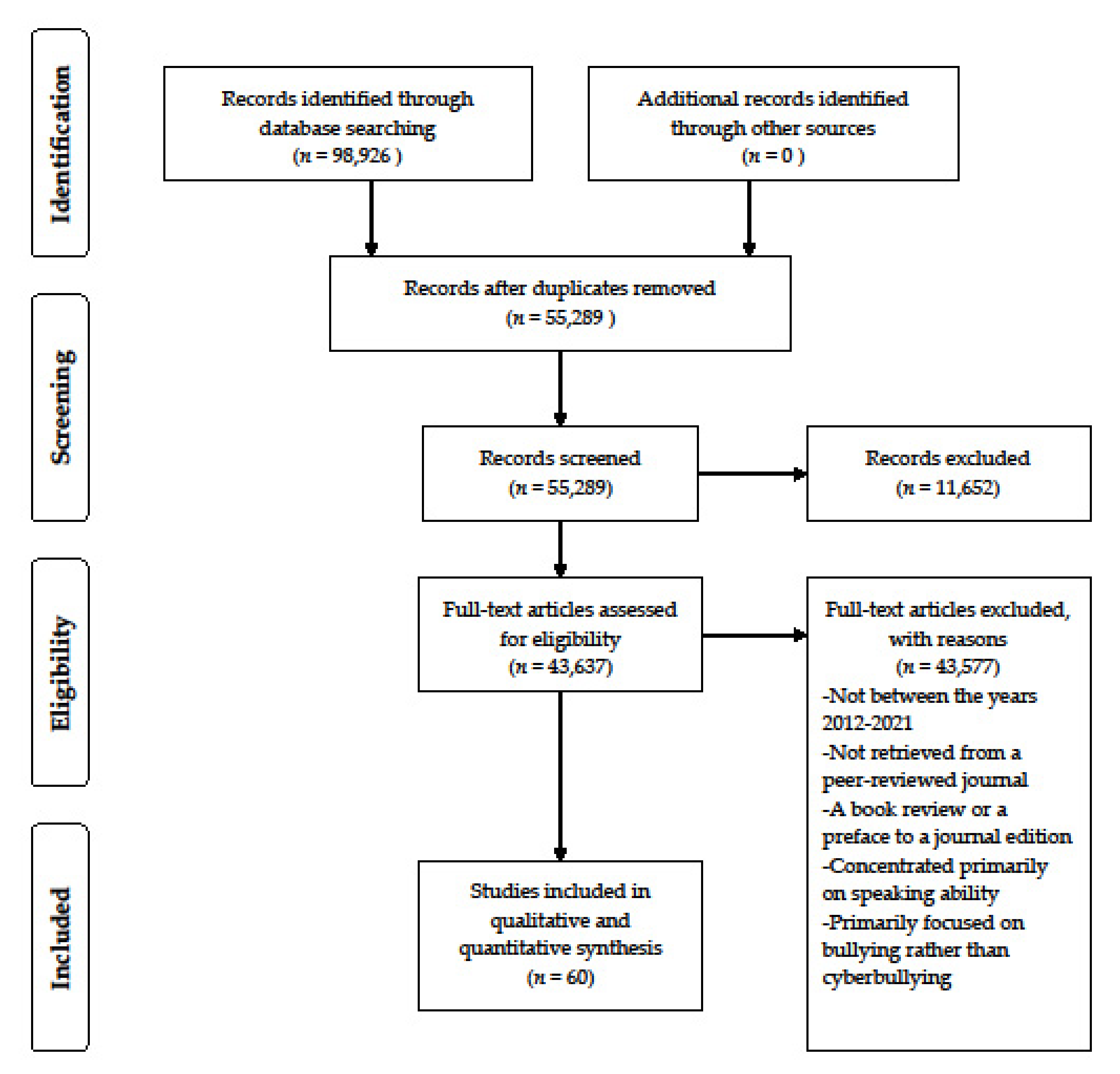

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scoping Review Research Question

2.2. Relevant Studies

- i.

- “How does speaking with accent lead to cyberbullying”, with 87 results from ERIC database and 830 results from Google Scholar;

- ii.

- “Speaking with accent” (20 results from ERIC website) (63.400 results from Google Scholar);

- iii.

- “Attitudes towards speakers of non-native English accent” (1749 results from ERIC website) (16.100 results from Google Scholar);

- iv.

- “Cyberbullying of teachers” (40 results from ERIC website) (16.700 results from Google Scholar).

2.3. Study Selection: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Charting the Data

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cerrato, L. Accent discrimination in the US: A hindrance to your employment and career development? International Degree. Programmes Thesis, European Business Administration, Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences. 2017. Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/129361/Cerrato_Laura.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Mitterer, H.; Eger, N.A.; Reinisch, E. My English sounds better than yours: Second language learners perceive their own accent as better than that of their peers. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 227643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, R. A Short Note on Accent–bias, Social Identity and Ethnocentrism. Adv. Lang. Lit. Stud. 2017, 8, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bolenbaugh, M.; Foley-Nicpon, M.; Young, R.; Tully, M.; Grunewald, N.; Ramirez, M. Parental Perceptions of Gender Differences in Child Technology Use and Cyberbullying. Psychol. Sch. 2020, 57, 1657–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, C.; Zuin, A. Cyberbullying Bystanders and Moral Engagement: A Psychosocial Analysis for Pastoral Care. Pastor. Care Educ. 2018, 36, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.S. Socialized Perception and L2 Pronunciation among Spanish-Speaking Learners of English in Puerto Rico. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Derwing, T.M.; Munro, M.J. Symposium—Accentuating the Positive: Directions in Pronunciation Research. Lang. Teach. 2010, 43, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, W.E. A Social Psychology of Bilingualism. J. Soc. Issues 1967, 23, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Communications Minister: Criticism, Mocking of Science Teacher on DidikTV is Cyberbullying. Malay Mail. Available online: https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2021/02/20/communications-minister-criticism-mocking-of-science-teacher-on-didiktv-is/1951418 (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Mendez, J.J.; Bauman, S.; Guillory, R.M. Bullying of Mexican immigrant students by Mexican American students: An examination of intracultural bullying. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2012, 34, 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordquist, R. Definition of Accent in English Speech. Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-accent-speech-1689054 (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Jones, M.(n.d.). Dialect vs. Accent: Definitions, Similarities, & Differences. Available online: https://magoosh.com/english-speaking/dialect-vs-accent-differences-and-examples/ (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.; Islam, G.; Koyuncu, B. Non-native accents and stigma: How self-fulfilling prophesies can affect career outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Roberson, L.; Russo, M.; Briganti, P. Language diversity, non-native accents, and their consequences at the workplace: Recommendations for individuals, teams, and organizations. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2019, 55, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralova, Z.; Mala, E. Non-Native Teachers ̓Foreign Language Pronunciation Anxiety. Int. J. Technol. Incl. Educ. 2018, 7, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, E.; Thompson, A.S. Native and non-native speaker teachers: Contextualizing perceived differences in the Turkish EFL setting. LIF–Lang. Focus J. 2016, 2, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zalaquett, C.P.; Chatters, S.J. Cyberbullying in college: Frequency, characteristics, and practical implications. Sage Open 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.E.; Wang, L.M. Effects of noise, reverberation and foreign accent on native and non-native listeners’ performance of English speech comprehension. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 139, 2772–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daftari, G.E.; Tavil, Z.M. The Impact of Non-native English Teachers’ Linguistic Insecurity on Learners’ Productive Skills. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 2017, 13, 379–398. [Google Scholar]

- Śliwa, M.; Johansson, M. How non-native English-speaking staff are evaluated in linguistically diverse organizations: A Socioling. Perspective. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 1133–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Ain, Q. Effects of non-native instructors’ L1, beliefs and priorities on pronunciation pedagogy at secondary level in district Rajanpur, Pakistan. J. Lang. Cult. Educ. 2019, 7, 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Frideger, M.; Pearce, J.L. Political skill: Explaining the effects of non- native accent on managerial hiring and entrepreneurial investment decisions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharkhiz Arabani, A.; Fathi, J.; Balalaei Somehsaraei, R. The effect of use of native- accent and non-native accent materials on the Iranian EFL learners’ listening comprehension: An EIL perspective. Int. J. Res. Engl. Educ. 2019, 4, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Muzamil, M.; Shah, G. Cyberbullying and self-perceptions of students associated with their academic performance. Int. J. Educ. Dev. Using Inf. Commun. Technol. (IJEDICT) 2016, 12, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Larrañaga, E.; Navarro, R.; Yubero, S. Socio-cognitive and emotional factors on perpetration of cyberbullying. Media Educ. Res. J. 2018, 56, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, T.; Mishna, F.; McInroy, L.B.; Shariff, S. Children’s experiences of cyberbullying: A Canadian national study. Child. Sch. 2015, 37, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, M.A.; Ovedovitz, A.C. Cyberbullying among College Students: A Look at Its Prevalence at a U.S. Catholic University. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 2018, 4, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Goodine, P. Exploring and Mitigating the Impact of Cyberbullying on Adolescents’ Mental Health. BU J. Grad. Stud. Educ. 2016, 8, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, W.; Faucher, C.; Jackson, M. What Parents Can Do to Prevent Cyberbullying: Students’ and Educators’ Perspectives. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, S.; Coyne, I.; Sprigg, C.; Axtell, C.; Subramanian, G. Exploring the impact of workplace cyberbullying on trainee doctors. Med Educ. 2015, 49, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, I.; Farley, S.; Axtell, C.; Sprigg, C.; Best, L.; Kwok, O. Understanding the relationship between experiencing workplace cyberbullying, employee mental strain and job satisfaction: a dysempowerment approach. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 945–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, S.; Coyne, I.; D’Cruz, P. Cyberbullying at work: Understanding the influence of technology. Concepts Approaches Methods 2021, 233–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyar, M.N.; Saeed, M.; Usta, A.; Shafique, I. Workplace cyberbullying and creativity: Examining the roles of psychological distress and psychological capital. Manag. Res. Rev. 2020, 44, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singthong, T. Impacts of Cyberbullying in the Workplace. Available online: https://archive.cm.mahidol.ac.th/handle/123456789/3513 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Poledňová, I.; Stránská, Z.; Čechová, M. Cyberbullying as a Form of Violence against Teachers in the Czech Republic. In Proceedings of the ICT Management for Global Competitiveness and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies Conference Theme: Economic, Social, and Psychological Aspects of ICT Implementation, Wrocław, Poland, 16–17 September 2013; p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, A.; Kee, D.M.H.; Ahmed, A. Workplace cyberbullying and interpersonal deviance: understanding the mediating effect of silence and emotional exhaustion. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, J.; Snyman, R. The tangled web: consequences of workplace cyberbullying in adult male and female employees. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 35, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhulo, J.N. Cyberbullying: Effect on work place production. Afr. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2019, 2, 24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.S. Cyberbullying and the Workplace: An Analysis of Job Satisfaction and Social Self-Efficacy. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, O. Relative impact of pronunciation features on ratings of non-native speakers’ oral proficiency. In Proceedings of the 4th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference, Ames, IA, USA, 24 August 2012; pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, C.W. Non-native pre-service English teachers’ narratives about their pronunciation learning and implications for pronunciation training. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Engl. Lit. 2014, 3, 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlbrecht, J.J. College Student Rankings of Multiple Speakers in a Public Speaking Context: A Language Attitudes Study on Japanese-accented English with a World Englishes Perspective. Ph.D. Dissertation, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, M. Attitudes towards Native and Non-Native Accents of English. Ph.D. Dissertation, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, G. Native or Non-Native-Speaking Teaching for L2 Pronunciation Teaching? An Investigation on Their Teaching Effect and Students’ Preferences. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2016, 9, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuse, A.; Navichkova, Y.; Alloggio, K. Perception of intelligibility and qualities of non-native accented speakers. J. Commun. Disord. 2018, 71, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, J.N.; Gottdiener, W.; Martin, H.; Gilbert, T.C.; Giles, H. A meta-analysis of the effects of speakers’ accents on interpersonal evaluations. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojastehrad, S.; Rafik-Galea, S.; Abdullah, A.N. International Students’ Attitudes Towards Malaysian English Ethnolects. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2015, 8, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Z.T.; Abdullah, A.N.; Heng, C.S. Malaysian university students’ attitudes towards six varieties of accented speech in English. Adv. Lang. Lit. Stud. 2014, 5, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, A.C.L. The Effect of Accent Strength in Lecturers’ Dutch-English Pronunciation on the Speaker Evaluations of Dutch Students with Different Study Backgrounds. 2018. Available online: https://theses.ubn.ru.nl/handle/123456789/6095?locale-attribute=en (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Kaur, P.; Raman, A. Exploring native speaker and non-native speaker accents: The English as a Lingua Franca perspective. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 155, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.C.A.; Roh, T.R.D.G. The effect of language attitudes on learner preferences: A study on South Koreans’ perceptions of the Philippine English accent. ELTWorldOnline.Com 2013, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Monfared, A.; Khatib, M. English or Englishes? Outer and expanding circle teachers’ awareness of and attitudes towards their own variants of English in ESL/EFL teaching contexts. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. (Online) 2018, 43, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, A.W. Attitudes towards Indonesian Teachers of English and Implications for their Professional Identity. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsou, S.Y.; Chen, Y. Taiwanese University Students’ Perceptions toward Native and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers in EFL Contexts. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2019, 31, 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Zahro, S.K. Native and Non-Native Listeners Perceptual Judgement of English Accentedness, Intelligibility, and Acceptability of Indonesian Speakers. Ling. Cult. 2019, 13, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkinshaw, I.; Duong, O.T.H. Native-and Non-Native Speaking English Teachers in Vietnam: Weighing the Benefits. Tesl-Ej 2012, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Walkinshaw, I.; Oanh, D.H. Native and non-native English language teachers: Student perceptions in Vietnam and Japan. Sage Open 2014, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardak, M. Native and Non-Native English Speaking Teachers’ Advantages and Disadvantages. Arab World Engl. J. 2014, 5, 124–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, R. Non-native EFL Teachers’ Perception of English Accent in Teaching and Learning: Any Preference? Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2018, 8, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilus, Z. Exploring ESL learners’ attitudes towards English accents. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 21, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Fauzi, N.M.; Hashim, H. Apple vs." Mangosteen": A Qualitative Study of Students’ Perception towards Native and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers. J. Educ. E-Learn. Res. 2020, 7, 218–228. [Google Scholar]

- Karakaş, A. Students’ perceptions of ‘Good English’ and the underlying ideologies behind their perceptions. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 2017, 13, 487–509. [Google Scholar]

- Alseweed, M.A. University Students’ Perceptions of the Influence of Native and Non- Native Teachers. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2012, 5, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Benzies, Y.J. English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) in ESP Contexts. Students’ Attitudes towards Non-Native Speech and Analysis of Teaching Materials. Alicante J. Engl. Stud. 2017, 30, 27–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chang, F.R. Taiwanese University Students’attitudes to Non-Native Speakers English Teachers. Teflin J. 2016, 27, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, N.R. Students’ preferences regarding native and non-native teachers of English at a university in the French Brittany. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 173, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuangkarn, K.; Rimkeeratikul, S. An Observational Study on the Effects of Native English-Speaking Teachers and Non-Native English-Speaking Teachers on Students’ English Proficiency and Perceptions. Arab World Engl. J. (AWEJ) 2020, 11, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candan, K.; Inal, D. EFL Learners’ Perceptions on Different Accents of English and (Non)Native English-Speaking Teachers in Pronunciation Teaching: A Case Study Through the Lens of English as an International Language. Engl. Int. Lang. 2020, 15, 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, B.; van Meurs, F.; Usmany, N. The effects of lecturers’ non-native accent strength in English on intelligibility and attitudinal evaluations by native and non-native English students. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021, 1362168820983145, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, D.O.; Ninggal, M.T.; Bolu-Steve, F.N. Relationship between Demographic Factors and Undergraduates’ Cyberbullying Experiences in Public Universities in Malaysia. Int. J. Instr. 2020, 13, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotler, J.L.; Fryling, M.; Rivituso, J. Causes of cyberbullying in multi-player online gaming environments: Gamer perceptions. J. Inf. Syst. Appl. Res. 2017, 10, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H.; Lee, H. Cyberbullying: Its Social and Psychological Harms among Schoolers. Int. J. Cybersecur. Intell. Cybercrime 2021, 4, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roessel, J.; Schoel, C.; Stahlberg, D. Modern notions of accent-ism: Findings, Conceptualizations, and implications for interventions and research on non-native accents. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 39, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassev, V.V. University Students’ Preferences of Assessing Levels of Intelligibility and Comprehensibility of Native English Teachers’(NETs) Accents Compared to Non- native English Teachers’(NNETs) Accents: A Case-Study with Undergraduate Students at Huachiew Chalerm. Asian J. Lit. Cult. Soc. 2020, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

| Search Terms | Limiters | Databases | Search Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| How does speaking with an accent lead to cyberbullying | Articles from 2012–2021 | ERIC website electronic database | 87 |

| Google Scholar electronic database | 830 | ||

| Speaking with an accent | Articles from 2012–2021 | ERIC website electronic database | 20 |

| Google Scholar electronic database | 63.400 | ||

| Attitudes toward speakers of non-native English accent | Articles from 2012–2021 | ERIC website electronic database | 1749 |

| Google Scholar electronic database | 16.100 | ||

| Cyberbullying of teachers | Articles from 2012–2021 | ERIC website electronic database | 40 |

| Google Scholar electronic database | 16.700 |

| Author | Year | Location | Research Design | Sample | Main Findings | Database | Dominant Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | 2017 | Italy | Quantitative | Numbers of sample are not stated. | Speaking with a non-native accent may cause speakers to (i) feel excluded and undervalued at work and (ii) adopt an avoidance strategy at work. | Google Scholar | Affective |

| [17] | 2019 | USA | Quantitative | n = 99 | Non-native speakers reported stereotype threat, worry, weariness, status loss, unpleasant emotions, avoidance goal orientations, and avoidance. Furthermore, non-native speakers reported cognitive fatigue as a result of conversing in a foreign language. | Google Scholar | Affective |

| [18] | 2018 | Slovakia | Quantitative (Scale and Test) | n = 100 | The positive association between age and pronunciation anxiety and negative relationship between age and pronunciation quality contradicts the common view that teaching experience duration is a role in reducing NNESTs’ nervousness. | ERIC | Affective |

| [19] | 2016 | Turkey | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 160 | The learners’ great tolerance for ambiguity in the classroom helps explain the perceived effectiveness of NESTs. | Google Scholar | Affective |

| [20] | 2014 | USA | Qualitative (Survey) | n = 613 | College students reported that cyberbullying made them unhappy, angry, or agitated, and increased their stress, demonstrating that the psychological impact of cyberbullying does not fade as the victim ages. | Google Scholar | Affective |

| [21] | 2016 | USA | Quantitative (Comprehension tasks) | n = 115 | Although greater background noise levels were often more detrimental to listeners with poor language skills, all listeners exhibited significant comprehension impairments with native speakers of English over RC-40. However, with Chinese speakers, the figure was lower. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [22] | 2017 | Turkey | Quantitative (Questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and proficiency tests) | Teachers n = 18 Learnersn = 300 | The linguistic insecurity of NNESTs, female and male, is not significantly connected to the learners’ writing and speaking scores. | ERIC | Behavioral |

| [23] | 2014 | UK | Qualitative (Interviews and Reflections) | n = 54 | Generally, native English-speaking workers hold high positions and make critical decisions, whereas non-native English speakers hold more subordinate roles and have less input into organizational administration and decision making. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [24] | 2019 | Pakistan | Qualitative (Interviews and observations) | n = 60 | A scarcity of English language subject specialists affects the students’ speaking skill. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [25] | 2013 | USA | Quantitative | n = 179 | Non-native English speakers are less likely to be recommended for a position in middle management and have significantly lower chances of obtaining new-venture funding. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [26] | 2019 | Iran | Quantitative (Quick Placement Test, Pearson Test ofEnglish General) | n = 60 | Using non-native accent listening materials was more effective than using native-accent resources in improving EFL learners’ listening comprehension. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [27] | 2016 | Pakistan | Quantitative (Survey) | n = 610 | When socioeconomic status is not taken into account in the model, cyberbullying may considerably and negatively impact students’ academic achievement. | ERIC | Behavioral |

| [28] | 2018 | Spain | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 1062 | Cyberbullying crime was connected with cyberbullying victimization, bullying violence, moral disengagement from cyberbullying, social support, and display of enjoyment. | ERIC | Behavioral |

| [29] | 2015 | Canada | Qualitative (Survey) | n = 1001 | Children who are cyberbullied are more likely to have unfavorable outcomes across all eight categories studied. | ERIC | Behavioral |

| [30] | 2018 | USA | Qualitative (Survey) | n = 187 | Cyberbullying results in lower self-esteem, anxiety, and loss or withdrawal from social relationships and experiences. | ERIC | Behavioral |

| [31] | 2016 | Canada | Qualitative (Survey) | n = 145 | With increased access to advanced technology and teenage fascination with it, cyberbullying is on the rise, and its harmful impacts on youth are being witnessed at school and at home. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [32] | 2018 | Canada | Qualitative (Survey, interviews) | n = 192 | Parental supervision of computer usage, students’ willingness to alert parents about cyberbullying, and how students and educators view the role of parents in cyberbullying prevention and promotion. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [33] | 2015 | UK | Quantitative (Survey) | n = 158 | Cyberbullying’s effects on trainee doctors. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [34] | 2017 | UK | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 331 | The effects of cyberbullying and offline bullying. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [35] | 2021 | UK | A mixed method (quantitative-qualitative) (Survey, interviews) | n = 144 | The impact of workplace cyberbullying and whether it is more severe than traditional bullying. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [36] | 2020 | Pakistan | Quantitative (Survey) | n = 329 | Cyberbullying in the workplace causes negative consequences. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [37] | 2021 | Thailand | Qualitative (Interviews) | n = 8 | Several consequences that occur to victims during and after cyberbullying. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [38] | 2013 | the Czech Republic | Quantitative (Survey) | n = 138 | Cyberbullying seems to be a type of abusive student’s behavior directed toward their teachers. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [39] | 2020 | Pakistan | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 351 | The findings, which are based on the conservation of resource theory and affective events theory, demonstrate that workplace cyberbullying affects interpersonal deviance. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [40] | 2020 | Australia | Quantitative (Survey) | n = 254 | The findings revealed that workplace cyberbullying increased perceived stress, which reflected worker’s unhappiness. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [41] | 2019 | Kenya | Qualitative (Interviews) | Numbers of samples are not stated. | The impact of cyberbullying at work negatively influences productivity owing to psychological trauma, legal engagement, and embarrassment when it becomes public. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [42] | 2019 | USA | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 205 | Being cyberbullied resulted in reduced social self-efficacy, and having lower social self-efficacy was related to reduced levels of work satisfaction. | Google Scholar | Behavioral |

| [43] | 2013 | USA | Quantitative (Speaking test) | n = 120 | The impact of pronunciation factors on judgments of non-native speakers’ oral competency had a hierarchical priority. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [44] | 2014 | Taiwan | Quantitative | Pre-service teachers n = 58 | Same attitude to their roles as non-native English speakers concerning pronunciation development and teaching. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [45] | 2018 | USA | Quantitative (Survey) | n = 40 | Focusing on intelligibility rather than flawless mastery of an idealized variation of English would benefit English learners and practitioners. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [46] | 2020 | Flanders and the UK | Quantitative (Survey) | n = 232 | Non-native English accents are accepted. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [47] | 2016 | China | Quantitative (Pre- and post-tests, questionnaires) | n = 30 | The participants’ comprehensibility and accentedness enhanced significantly. The majority of the participants would rather have a native speaking teacher than a non-native speaking teacher as their oral English teacher. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [48] | 2018 | USA | Quantitative (Survey) | Numbers of sample are not stated. | Strong connections exist between the view of intelligibility and the perception of non-native speakers’ personal attributes. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [49] | 2012 | USA | Quantitative | n = 20 | These findings support previous studies, indicating that speakers’ accents significantly impact how others perceive them. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [50] | 2015 | Malaysia | Mixed methods (quantitative-qualitative) (Survey) | n = 372 | A strong positive correlation exists between each ethnic group’s attitude toward the Malaysian English variety spoken and the intelligibility of that specific variation, which significantly influences listeners’ opinion of the speaker’s social attractiveness. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [51] | 2014 | Malaysia | Quantitative (Verbal-guise technique) | n = 120 | The students displayed an in-group accent bias, which meant that they rated non-native lecturers’ accents more highly. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [52] | 2018 | The Netherlands | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 183 | Non-native English listeners’ assessment of attitude was influenced by degree of accentedness in English, educational background, and language sensitivity. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [53] | 2014 | Malaysia | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 36 | In terms of correctness, acceptability, pleasantness, and familiarity, respondents consistently evaluated native speaker accents higher than non-native speaker accents. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [54] | 2013 | Philippines | Mixed methods (quantitative-qualitative) (Survey) | n = 120 Korean participants | Koreans are particularly susceptible to Philippine English vowel and consonant variations. When given the option of having a Philippine English speaker as their English teacher, the majority of the sample gave a negative response. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [55] | 2018 | India and Iran | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 260 | Alongside supporting and honoring different variations of English, recognizing and encouraging measures to improve teacher and learner awareness of the global expansion of English are critical. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [56] | 2015 | Indonesia | Qualitative (Interviews) | n = 204 | Generally, neither native English speakers nor non-native English speakers are favored by the perceived attributes of an ideal English instructor established in this study. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [57] | 2019 | Taiwan | Qualitative (Two open-ended questions) | n = 20 | Generally, the participants preferred NESTs over NNESTs. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [58] | 2019 | Indonesia | Qualitative (Case study) | n = 10 | Despite having a very strong accent, speeches with clear and accurate pronunciation are considered highly accepted and totally understood. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [59] | 2012 | Vietnam | Quantitative (Survey, questionnaire) | n = 50 | Advanced English respondents chose native speaker of English because they regarded native speaker as the best model to learn pronunciation. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [60] | 2014 | Vietnam and Japan | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 100 | Students perceived NESTs as representations of proper language use and pronunciation, as well as cultural information repositories. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [61] | 2014 | Afghanistan and UK | Mixed methods(Questionnaire, structured interviews) | n = 90 | Students highlighted the following strengths of their NESTs in questionnaires and structured interviews: teaching ability, grammaticality and idiomaticity, usage of the standard English language accent, and competency in managing spontaneous replies in the classroom. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [62] | 2018 | Hong Kong | Mixed methods (quantitative-qualitative) (A listening task, survey, interview) | n = 21 | The findings suggest that all participants favored native English as the paradigm of teaching and learning. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [63] | 2013 | Malaysia | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 34 | Using a native accent as a model for pronunciation acquisition is a more practical alternative. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [64] | 2020 | Malaysia | Qualitative (Essay writing) | n = 30 | Most students had a poor opinion of NNESTs, particularly when it came to teaching grammar and speaking skills. The NESTs, despite being evaluated favorably at the start of the study, had a rise in negative responses from students. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [65] | 2017 | Turkey | Mixed methods (quantitative-qualitative) (Questionnaire) | n = 42 | Specific ideologies, such as standard English, native-speakerism, and authenticity impact many students’ normative judgments of good English. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [66] | 2012 | Saudi Arabia | Mixed methods (quantitative-qualitative) (Questionnaire, interviews) | n = 169 | As the respondents progress to higher levels, NESTs become more popular. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [67] | 2017 | Spain | Qualitative (Textbooks analysis) | n = 14 | Law students tend to appreciate native accents more than non-native accents, although tourism students typically accept native and non-native accents. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [68] | 2016 | Taiwan | Quantitative (Questionnaire, interview) | n = 200 | Taiwanese students’ sentiments regarding their non-native speaking English teachers are positive and favorable. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [69] | 2015 | France | Quantitative (Survey) | n = 78 | The majority of respondents stated that they preferred native English speakers as educators. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [70] | 2020 | Thailand | Mixed methods (quantitative-qualitative) (Classroom observations, interviews) | n = 252 | NESTs score better agreeability with teachers’ teaching abilities, English abilities, and the establishment of an interesting learning environment. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [71] | 2020 | Turkey | Mixed methods (quantitative-qualitative) (Survey, interviews) | n = 169 | Many participants agreed that proper pronunciation is essential in communication, and if a pronunciation is intelligible, it can be considered as good. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [72] | 2021 | Netherlands | Quantitative (Questionnaire) | n = 522 | Dutch and foreign non-native listeners rated moderately non-native accented lecturers adversely compared with lecturers with slight or native accents. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [73] | 2020 | Malaysia | Quantitative (Survey) | n = 400 | Gender and program of study are more predictive of undergraduates’ cyberbullying experiences than race. | ERIC | Cognitive |

| [74] | 2016 | USA | Qualitative (Survey) | n = 936 | The major reasons for cyberbullying are anonymity, the cyberbully not realizing the real-life consequences of their actions, and a lack of fear toward punishment. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

| [75] | 2021 | USA | Quantitative (Survey) | n = 823 | Adult and peer assistance decreased the social and psychological suffering caused by cyberbullying. | Google Scholar | Cognitive |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, K.H.; Jospa, M.E.a.W.; Mohd-Said, N.-E.; Awang, M.M. Speak like a Native English Speaker or Be Judged: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312754

Tan KH, Jospa MEaW, Mohd-Said N-E, Awang MM. Speak like a Native English Speaker or Be Judged: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312754

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Kim Hua, Michelle Elaine anak William Jospa, Nur-Ehsan Mohd-Said, and Mohd Mahzan Awang. 2021. "Speak like a Native English Speaker or Be Judged: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312754

APA StyleTan, K. H., Jospa, M. E. a. W., Mohd-Said, N.-E., & Awang, M. M. (2021). Speak like a Native English Speaker or Be Judged: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312754