Group Medical Care: A Systematic Review of Health Service Performance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

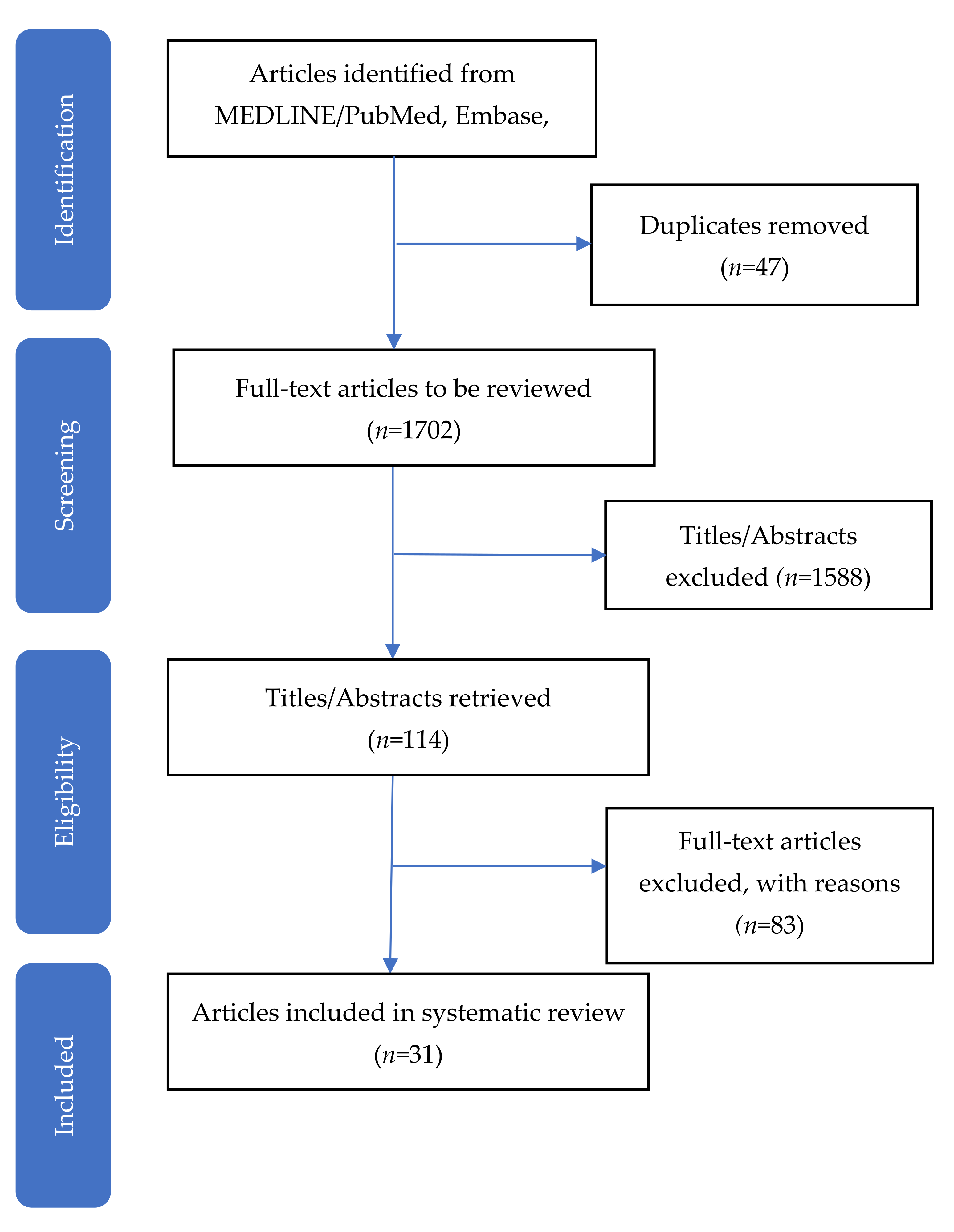

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Triple Aim 1: Patient Experience

3.2. Triple Aim 2: Health Outcomes

3.2.1. Pregnancy

3.2.2. Diabetes

3.2.3. Other Chronic Health Conditions

3.3. Triple Aim 3: Cost of Health Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parikh, M.; Rajendran, I.; D’Amico, S.; Luo, M.; Gardiner, P. Characteristics and components of medical group visits for chronic health conditions: A systematic scoping review. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2019, 25, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noffsinger, E.B. The drop-in group medical appointment model: A revolutionary access solution for follow-up visits. In Running Group Visits in Your Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jaber, R.; Braksmajer, A.; Trilling, J. Group visits for chronic illness care: Models, benefits and challenges. Fam. Pract. Manag. 2006, 13, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ramdas, K.; Darzi, A. Adopting innovations in care delivery—The case of shared medical appointments. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1105–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magriples, U. Group prenatal care. In UpToDate; Lockwood, C.J., Chakrabarti, A., Eds.; UpToDate: Waltham, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.; Darzi, A.; Egger, G.; Ickovics, J.; Noffsinger, E.; Ramdas, K.; Stevens, J.; Sumego, M.; Birrell, F. Process and systems: A systems approach to embedding group consultations in the NHS. Future Healthc. J. 2019, 6, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramdas, K.; Teisberg, E.; Tucker, A.L. Four ways to reinvent service delivery. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsh, S.R.; Aron, D.C.; Johnson, K.D.; Santurri, L.E.; Stevenson, L.D.; Jones, K.R.; Jagosh, J. A realist review of shared medical appointments: How, for whom, and under what circumstances do they work? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McNeil, D.A.; Vekved, M.; Dolan, S.M.; Siever, J.; Horn, S.; Tough, S.C. A qualitative study of the experience of centeringpregnancy group prenatal care for physicians. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13 (Suppl. S1), S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Edelman, D.; Gierisch, J.M.; McDuffie, J.R.; Oddone, E.; Williams, J.W. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartley, K.B.; Haney, R. Shared medical appointments: Improving access, outcomes, and satisfaction for patients with chronic cardiac diseases. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2010, 25, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catling, C.J.; Medley, N.; Foureur, M.; Ryan, C.; Leap, N.; Teate, A.; Homer, C.S. Group versus conventional antenatal care for women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD007622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, E.B.; Temming, L.A.; Akin, J.; Fowler, S.; Macones, G.A.; Colditz, G.A.; Tuuli, M.G. Group prenatal care compared with traditional prenatal care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wadsworth, K.H.; Archibald, T.G.; Payne, A.E.; Cleary, A.K.; Haney, B.L.; Hoverman, A.S. Shared medical appointments and patient-centered experience: A mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berwick, D.M.; Nolan, T.W.; Whittington, J. The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stiefel, M.N.; Nolan, K. Guide to measuring the triple aim: Population health, experience of care, and per capita cost. In IHI Innovation Series White Paper; Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kotelchuck, M. The adequacy of prenatal care utilization index: Its us distribution and association with low birthweight. Am. J. Public Health 1994, 84, 1486–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennedy, H.P.; Farrell, T.; Paden, R.; Hill, S.; Jolivet, R.R.; Cooper, B.A.; Rising, S.S. A randomized clinical trial of group prenatal care in two military settings. Mil. Med. 2011, 176, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ickovics, J.R.; Kershaw, T.S.; Westdahl, C.; Magriples, U.; Massey, Z.; Reynolds, H.; Rising, S.S. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beck, A.; Scott, J.; Williams, P.; Robertson, B.; Rn, D.J.; Gade, G.; Cowan, P. A randomized trial of group outpatient visits for chronically ill older HMO members: The cooperative health care clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997, 45, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.C.; Conner, D.A.; Venohr, I.; Gade, G.; McKenzie, M.; Kramer, A.M.; Bryant, L.; Beck, A. Effectiveness of a group outpatient visit model for chronically ill older health maintenance organization members: A 2-year randomized trial of the cooperative health care clinic. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 1463–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.H.; Grothaus, L.C.; Sandhu, N.; Galvin, M.S.; McGregor, M.; Artz, K.; Coleman, E.A. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: A system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, M.P.; Liu, C.F.; Taylor, L.; Souza, P.E.; Yueh, B. Hearing aid effectiveness after aural rehabilitation: Individual versus group trial results. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2013, 50, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, D.E.; Huang, P.; Okonofua, E.; Yeager, D.; Magruder, K.M. Group visits: Promoting adherence to diabetes guidelines. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaughan, E.M.; Johnston, C.A.; Cardenas, V.J.; Moreno, J.P.; Foreyt, J.P. Integrating chws as part of the team leading diabetes group visits: A randomized controlled feasibility study. Diabetes Educ. 2017, 43, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, D.C.; Williams, W.; Hall, E.G.; Heroux, R.; Bennett-Lewis, T. Imbedding interdisciplinary diabetes group visits into a community-based medical setting. Diabetes Educ. 2016, 42, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cohen, L.B.; Taveira, T.H.; Khatana, S.A.; Dooley, A.G.; Pirraglia, P.A.; Wu, W.C. Pharmacist-led shared medical appointments for multiple cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2011, 37, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, D.; Handley, M.; Wang, F.; Hammer, H. Effects of self-management support on structure, process, and outcomes among vulnerable patients with diabetes: A three-arm practical clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2009, 32, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, W.-C.; Taveira, T.H.; Jeffery, S.; Jiang, L.; Tokuda, L.; Musial, J.; Cohen, L.B.; Uhrle, F. Costs and effectiveness of pharmacist-led group medical visits for type-2 diabetes: A multi-center randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ford, K.; Weglicki, L.; Kershaw, T.; Schram, C.; Hoyer, P.J.; Jacobson, M.L. Effects of a prenatal care intervention for adolescent mothers on birth weight, repeat pregnancy, and educational outcomes at one year postpartum. J. Perinat. Educ. 2002, 11, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ickovics, J.R.; Earnshaw, V.; Lewis, J.; Kershaw, T.S.; Magriples, U.; Stasko, E.; Rising, S.S.; Cassells, A.; Cunningham, S.; Bernstein, P.; et al. Cluster randomized controlled trial of group prenatal care: Perinatal outcomes among adolescents in new york city health centers. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kershaw, T.S.; Magriples, U.; Westdahl, C.; Rising, S.S.; Ickovics, J. Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for HIV prevention: Effects of an hiv intervention delivered within prenatal care. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 2079–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magriples, U.; Boynton, M.H.; Kershaw, T.S.; Lewis, J.; Rising, S.S.; Tobin, J.N.; Epel, E.; Ickovics, J.R. The impact of group prenatal care on pregnancy and postpartum weight trajectories. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 688.e1–688.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Felder, J.N.; Epel, E.; Lewis, J.B.; Cunningham, S.D.; Tobin, J.N.; Rising, S.S.; Thomas, M.; Ickovics, J.R. Depressive symptoms and gestational length among pregnant adolescents: Cluster randomized control trial of CenteringPregnancy® plus group prenatal care. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, S.; Hill, P.; Briggs, A.; Barbier, K.; Cahill, A.; Macones, G.; Colditz, G.; Tuuli, M.; Carter, E. The effect of group prenatal care for women with diabetes on social support and depressive symptoms: A pilot randomized trial. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ickovics, J.R.; Reed, E.; Magriples, U.; Westdahl, C.; Schindler Rising, S.; Kershaw, T.S. Effects of group prenatal care on psychosocial risk in pregnancy: Results from a randomised controlled trial. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gutierrez, N.; Gimple, N.E.; Dallo, F.J.; Foster, B.M.; Ohagi, E.J. Shared medical appointments in a residency clinic: An exploratory study among hispanics with diabetes. Am. J. Manag. Care 2011, 17, e212–e214. [Google Scholar]

- Taveira, T.H.; Friedmann, P.D.; Cohen, L.B.; Dooley, A.G.; Khatana, S.A.M.; Pirraglia, P.A.; Wu, W.-C. Pharmacist-led group medical appointment model in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taveira, T.H.; Dooley, A.G.; Cohen, L.B.; Khatana, S.A.; Wu, W.C. Pharmacist-led group medical appointments for the management of type 2 diabetes with comorbid depression in older adults. Ann. Pharmacother. 2011, 45, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, R.E.; Boyer, K.M.; Spanbauer, S.M.; Sprague, D.; Bingham, M. Effectiveness of prediabetes nutrition shared medical appointments: Prevention of diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2013, 39, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, D.; Fredrickson, S.K.; Melnyk, S.D.; Coffman, C.J.; Jeffreys, A.S.; Datta, S.; Jackson, G.L.; Harris, A.C.; Hamilton, N.S.; Stewart, H.; et al. Medical clinics versus usual care for patients with both diabetes and hypertension: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crowley, M.J.; Melnyk, S.D.; Ostroff, J.L.; Fredrickson, S.K.; Jeffreys, A.S.; Coffman, C.J.; Edelman, D. Can group medical clinics improve lipid management in diabetes? Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, A.; Crowley, M.J.; Coffman, C.; Edelman, D. Effect of a group medical clinic for veterans with diabetes on body mass index. Chronic Illn. 2019, 15, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, V.; Sole, M.L.; Norris, A.E. Improving the care of patients with chronic kidney disease using group visits: A pilot study to reflect an emphasis on the patients rather than the disease. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2016, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Masley, S.; Phillips, S.; Copeland, J.R. Group office visits change dietary habits of patients with coronary artery disease-the dietary intervention and evaluation trial (d.I.E.T.). J. Fam. Pract. 2001, 50, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Griffin, B.L.; Burkiewicz, J.S.; Peppers, L.R.; Warholak, T.L. International normalized ratio values in group versus individual appointments in a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2009, 66, 1218–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, D.E.; Dismuke, C.E.; Magruder, K.M.; Simpson, K.N.; Bradford, D. Do diabetes group visits lead to lower medical care charges? Am. J. Manag. Care 2008, 14, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E.A.; Eilertsen, T.B.; Kramer, A.M.; Magid, D.J.; Beck, A.; Conner, D. Reducing emergency visits in older adults with chronic illness. A randomized, controlled trial of group visits. Eff. Clin. Pract. 2001, 4, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, R.A.; Phillips, L.E.; O’Dell, L.; Husseini, R.E.; Carpino, S.; Hartman, S. Group prenatal care: A financial perspective. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lockwood, C.; Porrit, K.; Munn, Z.; Rittenmeyer, L.; Salmond, S.; Bjerrum, M.; Loveday, H.; Carrier, J.; Stannard, D. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Primary Author, Year | Sample | Study Setting | N | Mean Age; Sex, %; Race/Ethnicity, % b | Group Care Model: Type; Frequency, Duration; Number Patients Per Session (n)2 | Triple Aim 1: Patient Experience | Triple Aim 2: Population Health | Triple Aim 3: Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy | ||||||||

| Ford, 2002 | Pregnant adolescents | Five clinics in MI | 282 | Mean age: 18 years; 100% female; 94% African American, 4% Caucasian, 2% Other | Group and peer partner assignment for duration of prenatal care; groups met at scheduled clinic time; n = 6–8 | N/A | Significant:

| N/A |

| Felder, 2017 | (See Ickovics, 2016) | 1135 | Mean age: 18 years; 100% female; 58% Latina, 34% Black, 8% Other | (See Ickovics, 2016) | N/A | Significant:

| N/A | |

| Ickovics, 2007 | Pregnant adolescents and young adults | Two university-affiliated hospitals in CT and GA | 1047 | Mean age: 20 years; 100% female; 80% African American, 13% Latina, 6% White, 1% Mixed or Other | CP and CPP; 10 prenatal sessions, 120 min each; average n = 8 | Significant:

| Significant:

| Non-significant:

|

| Ickovics, 2011 | (See Ickovics, 2007) | N/A | Significant: Among subgroup with high psychosocial stress only:

| N/A | ||||

| Ickovics, 2016 | Pregnant adolescents and young adults | Fourteen urban health centers in NY | 1148 | Mean age: 19 years; 100% female; 58% Latina, 34% Black, 8% White or Other | CPP, 10 prenatal sessions, 120 min each; n = 8–12 | N/A | Significant:

| Non-significant:

|

| Kennedy, 2011 | Pregnant women on TRICARE | Two military clinics | 322 | Mean age: 25 years; 100% female; 59% White, 19% African American, 10% Latina, 5% Asian/Pacific Islander, 7% Other | CP; 9 prenatal sessions and 1 postpartum reunion; n = 6–12 | Significant:

| Non-significant:

| Non-significant:

|

| Kershaw, 2009 | (See Ickovics, 2007) | N/A | Significant:

| N/A | ||||

| Magriples, 2015 | (See Ickovics, 2016) | 984 | Mean age: 19 years; 100% female; 64% Black, 32% Latina, 4% Other | (See Ickovics, 2016) | N/A | Significant:

| N/A | |

| Mazzoni, 2018 | Pregnant women with Type II or gestational diabetes | Two diabetes clinics in CO and MO | 78 | Mean age: 31 years; 100% female; 53% Hispanic, 39% African American, 8% White | 4-session curriculum delivered to rotating cohort; every two weeks, 90–120 min each; n = 2–10 | N/A | Non-significant:

| N/A |

| Diabetes | ||||||||

| Berry, 2016 | Low-income adults with uncontrolled diabetes | Community-based health center in NC | 80 | Mean age: 51 years; 89% female, 11% male; 77% Black, 18% White, 2% Hispanic, 1% Asian Pacific, 1% American Indian | Five group classes; every 3 months for 15 months | Significant:

| Significant:

| Non-significant:

|

| Clancy, 2007 | Low-income adults with uncontrolled Type II diabetes | Primary medical center in SC | 186 | Mean age: 56 years; 72% female, 28% male; 83% African American, 17% Other | CHCC; monthly visits for 1 year, 120 min each; n = 14–17 | Significant:

| Non-significant:

| N/A |

| Clancy, 2008 | (See Clancy 2007) | N/A | N/A | Significant:

| ||||

| Cohen, 2011 | Adults with uncontrolled Type II diabetes and cardiovascular risk | VA Medical Center | 99 | Mean age: 70 years (group care), 67 years (usual care); 2% female, 98% male | VA-MEDIC-E; weekly for 4 weeks then monthly for 5 months, 120 min; n = 4–6 | Non-significant:

| Significant:

| N/A |

| Cole, 2013 | Adults with prediabetes | TRICARE beneficiaries in San Antonio, Texas | 65 | Mean age: 58 years; 46% females, 54% males; 64% Caucasian, 19% Hispanic, 17% African American | Nutrition-focused shared medical appointments; monthly for 3 months, 90 min each; n = 6–8 | N/A | Non-significant:

| N/A |

| Crowley, 2014 | (See Edelman 2010) | N/A | Significant:

| N/A | ||||

| Edelman, 2010 | Adults with uncontrolled Type II diabetes and hypertension | Two VA medical centers in NC and VA | 239 | Mean age: 63 years (group care), 61 years (usual care); 5% female, 95% male; 58% African American, 36% White, 5% Other | Group medical clinic; every 2 months for 12 months, 12 min each; n = 7–9 | N/A | Significant:

| Significant:

|

| Eisenberg, 2019 | (See Edelman 2010) | N/A | Non-significant:

| N/A | ||||

| Gutierrez, 2011 | Hispanic adults with Type II diabetes | Family medicine residency clinic in TX | 103 | 100% Hispanic | Shared medical appointments; twice per month for 9 months, 120 min each; mean n = 9 | N/A | Significant:

| N/A |

| Schillinger, 2009 | Adults with uncontrolled type II diabetes | County-run clinics in CA | 339 | Mean age: 56 years; 59% female, 41% male; 47% White/Latino, 23%Asian, 21% African American, 8% White/Non-Latino, 1% Other | Group medical visits; 9 monthly sessions, 90 min each; n = 6–10 | Non-significant:

| Significant:

| |

| Taveira, 2010 | Adults with uncontrolled Type II diabetes | VA medical center in RI | 109 | Mean age: 62 years (group care), 67 years (usual care); 5% female, 95% male; 91% White, 9% Other | VA-MEDIC;4 weekly sessions, 60 min each; n = 4–8 | N/A | Significant:

| N/A |

| Taveira, 2011 | Adults with Type II diabetes and comorbid depression | VA medical center in RI | 88 | Mean age: 60 years (group care), 61 years (usual care); 2% female, 98% male; 99% White, 1% Other | VA-MEDIC-D; 4 weekly sessions, 120 min each, followed by 5 monthly, 90 min each; n = 4–6 | N/A | Significant:

| Non-significant:

|

| Vaughan, 2017 | Low-income Hispanic adults with Type II diabetes | Community clinic in TX | 50 | Mean age: 51years (group care), 48 years (usual care); 80% female, 20% male; 100% Hispanic | Group visits with CHWs integrated as part of leadership team; 6 monthly sessions, 180 min each; maximum n = 10 | Significant:

| Significant:

| N/A |

| Wagner, 2001 | Adults over ≥30 years with diabetes | Group model HMO in WA | 707 | Mean age: 61years (group care), 60 years (usual care); 47% female, 53% male; 69% White, 31% Other | Group chronic care clinics; once every 3 to 6 months for 2 years; n = 6–10 | Significant:

| Non-significant:

| Significant:

|

| Wu, 2018 | Adults with uncontrolled type II diabetes and either hypertension, active smoking or hyperlipidemia | Three VA Hospitals in RI, CT, and HI | 250 | Mean age: 65 years; 4% female, 96% male | VA-MEDIC; 4 weekly sessions followed by 4 booster sessions held once every 3 months, 120 min each; n = 4–6 | Non-significant:

| Non-significant:

| Significant:

|

| Other Chronic Health Conditions | ||||||||

| Beck, 1997 | Chronically ill older adults (≥65 years) | Group model HMO in CO | 321 | Mean age: 72 years (group care), 75 years (usual care); 66% female, 34% male | CHCC; 12 monthly sessions, 120 min each; average n = 8 | Significant:

| Non-significant:

| Significant:

|

| Coleman, 2001 | Chronically ill older adults (≥60 years) | Group model HMO in CO | 295 | Mean age: 74 years; 59% female, 41% male | CHCC; 120 min; 24 monthly sessions, 120 min each; n = 8–12 | N/A | N/A | Significant:

|

| Collins, 2013 | Adults with hearing loss | VA audiology clinic in WA | 644 | Mean age: 66 years; 2% female, 98% male | Drop-in group medical appointment; one visit for fitting, 60 min, and one follow-up ~3–5 week later, 75 min (randomized separately); maximum n = 6 | Significant:

| Non-significant:

| Significant:

|

| Griffin, 2009 | Adults on warfarin therapy | Anticoagulation clinic in ambulatory care center in IL | 153 | Mean age: 75 years (group care), 67 years (usual care) | CHCC; twice weekly for 16 weeks, 60 min each; average n = 6 | N/A | Non-significant:

| N/A |

| Masley, 2001 | Adults with coronary artery disease and high lipid levels | Four community outpatient clinics in 3 cities in WA | 97 | Mean age: 66 years (group care), 64 years (usual care); 30% female, 70% male | CHCC; 14 group visits over 1 year, weekly for first month, then monthly for 10 months, 90 min each | N/A | Significant:

| Non-significant:

|

| Montoya, 2016 | Adults with stage 4 chronic kidney disease | Two outpatient nephrology clinics in FL | 30 | Mean age: not reported; 53% female, 47% male; 60% Caucasian, 23% African American, 10% Hispanic, 7% Other | Chronic Care Model; 6 monthly sessions; 90–120 min each; n = 13 | N/A | Non-significant:

| N/A |

| Scott, 2004 | (See Coleman 2001) | Significant:

| Non-significant:

| Significant:

| ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cunningham, S.D.; Sutherland, R.A.; Yee, C.W.; Thomas, J.L.; Monin, J.K.; Ickovics, J.R.; Lewis, J.B. Group Medical Care: A Systematic Review of Health Service Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312726

Cunningham SD, Sutherland RA, Yee CW, Thomas JL, Monin JK, Ickovics JR, Lewis JB. Group Medical Care: A Systematic Review of Health Service Performance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312726

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunningham, Shayna D., Ryan A. Sutherland, Chloe W. Yee, Jordan L. Thomas, Joan K. Monin, Jeannette R. Ickovics, and Jessica B. Lewis. 2021. "Group Medical Care: A Systematic Review of Health Service Performance" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312726

APA StyleCunningham, S. D., Sutherland, R. A., Yee, C. W., Thomas, J. L., Monin, J. K., Ickovics, J. R., & Lewis, J. B. (2021). Group Medical Care: A Systematic Review of Health Service Performance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312726