Canadian Career Firefighters’ Mental Health Impacts and Priorities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Approach/Design

2.2. Sampling, Recruitment, and Consent of Participants

2.3. Role of the Researchers

2.4. Data Collection Procedures

2.5. Analysis

2.6. Trustworthiness of Findings

3. Results

“There is more than just PTSD out there. PTSD is a bit of a fail. We’ve missed the opportunities to help people along the way.”

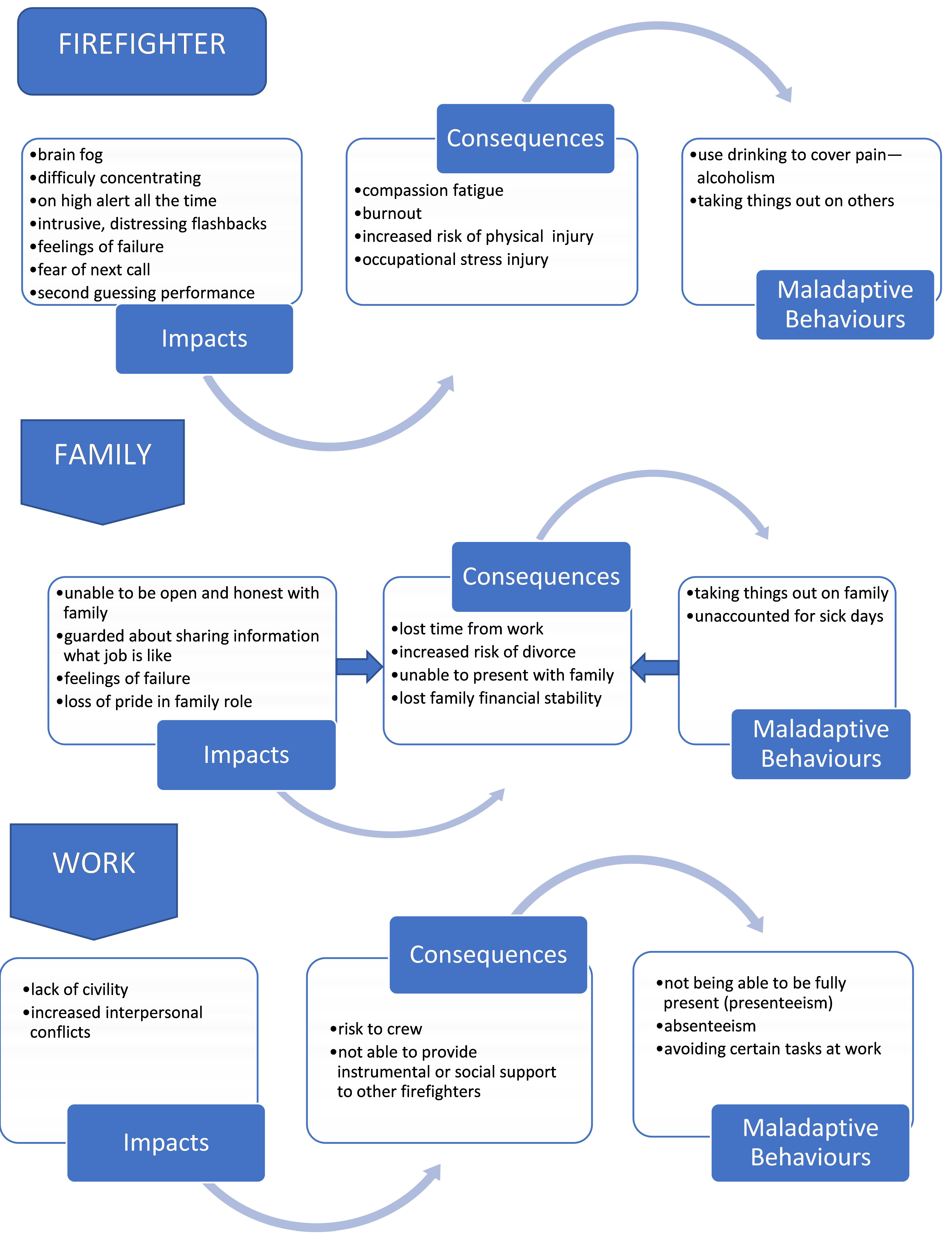

3.1. Impacts

“Someone in my office today that is off on post-traumatic stress disorder that is not recognized by the Workman’s Compensation Board, and he can’t sleep, doesn’t want to go on medical calls anymore, he has nightmares about coming back to work. He’s starting to drink, there’s substance abuse, there’s relationships issues, there’s divorces, impacts on the kids. It’s really large.”

3.1.1. Impacts on Firefighters

“I’ll give you an example. I came in on a person—she had hung herself, and I can still see her perfectly straight black hair, I can still see her pajamas, and I can still see her hanging there. And that was 15 years ago. It’s like I’m still standing there staring at her hanging from the ceiling. How does it affect you? I don’t know how it affects me, but it does. The memories stay.”

“Let’s go to the worst case scenario. You get there, and the whole family has passed away in the house fire. And what’ll happen is the firefighter will say, oh God, if we’d only got there, you know, one minute sooner, if I’d only taken this turn or that turn maybe we could have.”

3.1.2. Impacts on Firefighters’ Families

“So, it’s difficult when you talk to your loved ones, it can be your friends that aren’t firefighters—it just becomes very difficult because they don’t really get it. They think you’re upset about something, but they don’t know why and it causes a lot of—it can cause a lot of grief.”

“I’ve seen a psychologist for PTSD because of the things that I’ve seen and done. And I can say that it’s affected my family, in a way, that I do drink too much at times. And I don’t take it out on my family, but you don’t want to share with them, so you do hold a lot of things in.”

“Ideally, another firefighter because we’re—we’re a very kind of close-knit, closed group.”

“I could see something on a call, come home, have—put it in the back of my head for a couple of days, and then, you know, get into a fight with my spouse, and then all of a sudden, all that emotional weight from the call before comes out.”

“One’s very personal for me, being off on PTSD, it’s significant, it’s especially because you included families, that when I look at a divorce rate and the problems that we have at home, it’s just anecdotal, but I see them as higher.”

3.1.3. Impacts on Workplace

“I would say one of the things is interpersonal conflicts that can easily flare up due to stress.”

“… if you’re not dealing with it, you can get really bitter, really snappy with the guys.”

“Somebody has a very traumatic call, and they didn’t really have a good feeling about it, and then the next time they have an incident that’s quite similar to that, maybe it could bring back, you know, flashbacks and memories of the other one that kind of traumatized them, and it kind of take their focus away from doing their job safely and effectively.”

“You’re just not wanting to go to work because you don’t want to have another... maybe an infant call or, you know, another dead body or something. You don’t want to see that over and over again, so you maybe just book off sick, so that affects corporation, you know, overtime and everything else.”

“If I could go without, you know, serious repercussions, and, for instance, jump in a boat, and go clear my head fishing for the day, you just need to have the support from employers to go and clear your head, but it’s a fine line, because you don’t want to have people abuse it.”

“So, you become less of a team player, maybe not by choice but more by the effect of the mental strain or stress that you’re suffering from, from a critical incident or mental trauma. So those types of things definitely affect your firefighting.”

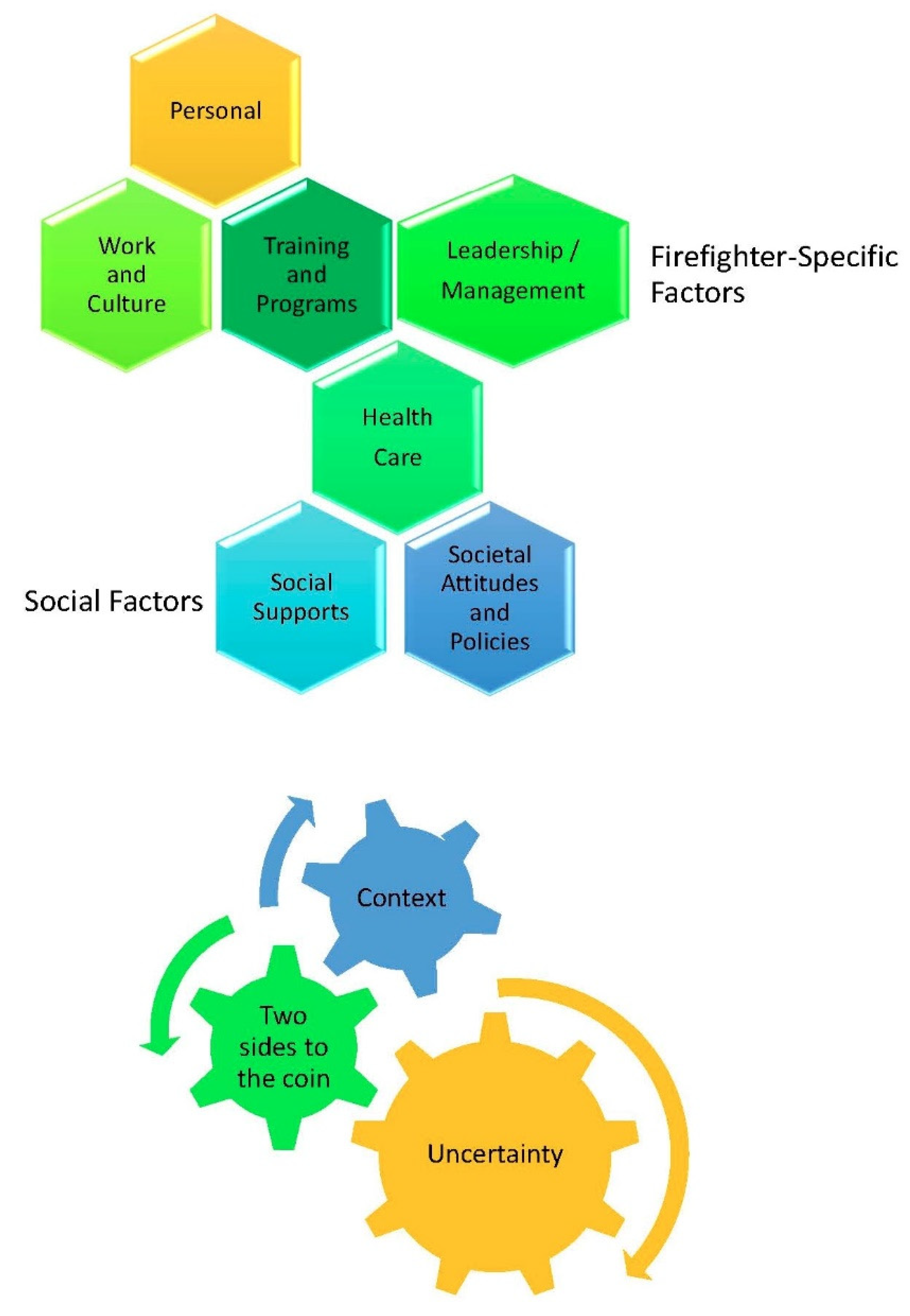

3.2. Barriers and Facilitators

“Healthy body, healthy mind…if we develop a good workout routine, it also alleviates stress, but you work on a healthy body, it’s going to help your mind.”

3.3. Firefighters’ Needs

“Should also include families … it was my ex-wife who picked up on all the pieces, but didn’t know what it was.”

“Come out with a list of incidents that are recognized as being unanimously traumatic for everyone and have a policy where immediately that crew should be taken out of service. They should have a chance to sit down and talk to someone about it.”

“The city needs to hire a psychologist or psychiatrist and get their opinion on how to treat members or firefighters that have mental health issues and get their opinion on how—one of the biggest things is access.”

“The gradual returning to work. You know, starting off with, you know, a few hours of coming into the station without being on the rigs or on the trucks. And then gradually, you know, to a day and then a night, doing a couple of night shifts at work. And then coming back into, you know, being back full time on duty sort of thing.”

3.4. Research Needs

- 1.

- Awareness and monitoring

- a.

- Trends in mental health

- i.

- Document the mental health challenges firefighters experience (goal increase awareness)

- ii.

- Bi-annual exams/surveys to monitor changes in physical and mental health

- 2.

- Understanding mental health

- a.

- Other mental health issues beyond PTSD

- b.

- The cumulative effects of mental health exposures

- c.

- Brain mechanisms that lead to mental health/PTSD issues

- d.

- Ways to measure exposures and outcomes

- 3.

- Better prevention and treatment

- a.

- Research on early signs and symptoms that a person is in trouble

- b.

- Design and evaluation of prevention and treatment programs

- 4.

- Access to care

- a.

- Geographic variations in programs/services

- b.

- Barriers to access to health care services

“Research—it can help individuals realise that… the things that we see and do that are negative are going to affect our mental health and that there is nothing, you know, there’s nothing wrong with that.”

“We need to understand what happens within our brain and how we can rewire that or have it wired appropriately and what that first 12 h means. So, what the first 24 h means and what we can do about it.”

“Death calls, … repetitive nuisance calls that just drive you crazy over a while … the same intoxicated people that you deal with everyday... obviously each call affects everybody else differently. We need to see if there’s actually a pattern to why people are affected or can’t deal with a certain kind of call.”

“How do we measure what stigma does to firefighters? How do we measure the culture? How can we measure that had we put in training in place?”

“I guess just to kind of see, you know, the percentage of people who have mental health and maybe just track the treatment and processes that they go through before they return to work to see what’s kind of effective and what’s not.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jacobsson, A.; Backteman-Erlanson, S.; Brulin, C.; Hörnsten, Å. Experiences of critical incidents among female and male firefighters. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2015, 23, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev, A.Y.; Freedman, S.; Peri, T.; Brandes, D.; Sahar, T.; Orr, S.P.; Pitman, R.K. Prospective Study of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression Following Trauma. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 1555, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komarovskaya, I.; Maguen, S.; McCaslin, S.E.; Metzler, T.J.; Madan, A.; Brown, A.D.; Galatzer-Levy, I.R.; Henn-Haase, C.; Marmar, C.R. The impact of killing and injuring others on mental health symptoms among police officers. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 1332–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corneil, W.; Beaton, R.; Murphy, S.; Johnson, C.; Pike, K. Exposure to traumatic incidents and prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptomatology in urban firefighters in two countries. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1999, 4, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, E.A.; Bennett, M. Development of a critical incident stress inventory for the emergency medical services. Traumatol. An. Int. J. 2014, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermid, J.C.; Nazari, G.; Rashid, C.; Sinden, K.; Carleton, N.; Cramm, H. Two-month point prevalence of exposure to critical incidents in firefighters in a single fire service. Work 2019, 62, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, G.; Sinden, K.E.; D’Amico, R.; Brazil, A.; Carleton, R.N.; Cramm, H.A. Prevalence of Exposure to Critical Incidents in Firefighters Across Canada. Work 2020, 67, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil, A. Exploring Critical Incidents and Postexposure Management in a Volunteer Fire Service. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2017, 26, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, E.J.; Best, S.R.; Lipsey, T.L.; Weiss, D.S. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.D.V.; Resick, P.A.; Griffin, M.G. Panic following trauma: The etiology of acute posttraumatic arousal. J. Anxiety Disord. 2004, 18, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Donnell, M.L.; Creamer, M.C.; Parslow, R.; Elliott, P.; Holmes, A.C.N.; Ellen, S.; Judson, R.; McFarlane, A.C.; Silove, D.; Bryant, R.A. A predictive screening index for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following traumatic injury. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkonigg, A.; Kessler, R.C.; Storz, S.; Wittchen, H.-U.H. Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: Prevalence, risk factors and comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000, 101, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Duranceau, S.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; MacPhee, R.S.; Groll, D.; et al. Mental Disorder Symptoms among Public Safety Personnel in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 070674371772382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carleton, R.N.; Dobson, K.S.; Keane, T.M.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Sareen, J.; MacPhee, R.S.; Hozempa, K.; Weekes, J.R.; et al. Suicidal Ideation, Plans, and Attempts Among Public Safety Personnel in Canada. Can. Psychol. 2018, 59, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cramm, H.; Norris, D.; Venedam, S.; Tam-Seto, L. Toward a Model of Military Family Resiliency: A Narrative Review. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2018, 10, 620–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norris, D.; Eichler, M.; Cramm, H.; Tam-Seto, L.; Smith-Evans, K. Operational Stress Injuries and the Mental Health and Well-Being of Veteran Spouses: A Scoping Review. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2018, 10, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McFarlane, A.C. Epidemiological evidence about the relationship between PTSD and alcohol abuse: The nature of the association. Addict. Behav. 1998, 23, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kales, S.N.; Soteriades, E.S.; Cristopi, C.A.; Christiani, D.C. Emergency Duties and Deaths from Heart Disease among Firefighters in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitman, S.C. Suicide in the Fire Service: Saving the Lives of Firefighters; Naval Postgraduate School: Monterey, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10945/48534 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Martin, C.E.; Tran, J.K.; Buser, S.J. Correlates of suicidality in firefighter/EMS personnel. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.E.; Vujanovic, A.A.; Paulus, D.J.; Bartlett, B.; Gallagher, M.W.; Tran, J.K. Alcohol use and suicidality in firefighters: Associations with depressive symptoms and post-traumatic stress. Compr. Psychiatry 2017, 74, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, T.L. Mortality of urban firefighters in Alberta, 1927–1987. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1993, 23, 921–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidotti, T.L. Occupational mortality among firefighters: Assessing the association. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 1995, 37, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, T.L. Health Risks and Fair Compensation in the Fire Service; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-31923-069-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, J.; Mol, E.; Visser, B.; Frings-Dresen, M. Risk of health complaints and disabilities among Dutch firefighters. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2004, 77, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahy, R.F.; LeBlanc, P.R.; Molis, J.L. Firefighter Fatalities in the United States; National Fire Protection Association: Quincy, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 1977–2009. Available online: http://www.nfpa.org/research/reports-and-statistics/the-fire-service/fatalities-and-injuries/firefighter-fatalities-in-the-united-states (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Frost, D.M.; Beach, T.A.C.C.; Crosby, I.; McGill, S.M. Firefighter injuries are not just a fireground problem. Work 2015, 52, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, P.W.; Suyama, J.; Hostler, D. A review of risk factors of accidental slips, trips, and falls among firefighters. Saf. Sci. 2013, 60, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezant, D.J.; Dhala, A.; Goldstein, A.; Janus, D.; Ortiz, F.; Aldrich, T.K.; Kelly, K.J. The incidence, prevalence, and severity of sarcoidosis in New York City firefighters. Chest 1999, 116, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahn, S.A.; Patel, J.H.; Lentz, C.W.; Bell, D.E. Firefighter burn injuries: Predictable patterns influenced by turnout gear. J. Burn Care Res. 2012, 33, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbitts, A.; Alden, N.E.; O’Sullivan, G.; Bauer, G.J.; Bessey, P.Q.; Turkowski, J.R.; Yurt, R.W. Firefighter Burn Injuries: A 10-Year Longitudinal Study. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 2004, 25, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, G.S.; Harris, R.B.; Pollack, K.M.; Peate, W.F.; Burgess, J.L. Beyond the fireground: Injuries in the fire service. Inj. Prev. 2012, 18, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airila, A.; Hakanen, J.J.; Luukkonen, R.; Lusa, S.; Punakallio, A.; Leino-Arjas, P. Developmental trajectories of multisite musculoskeletal pain and depressive symptoms: The effects of job demands and resources and individual factors. Psychol. Health 2014, 29, 1421–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, H.E.; Garten, R.S.; McMinn, D.R.; Beckman, J.L.; Kamimori, G.H.; Acevedo, E.O. Stress hormones and vascular function in firefighters during concurrent challenges. Biol. Psychol. 2011, 87, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Safety Canada. Supporting Canada’s Public Safety Personnel: An Action Plan on Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries; Public Safety Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019; p. 17. Available online: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/2019-ctn-pln-ptsi/index-en.aspx (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Johnson, C.C.; Vega, L.; Kohalmi, A.L.; Roth, J.C.; Howell, B.R.; Van Hasselt, V.B. Enhancing Mental Health Treatment for the Firefighter Population: Understanding Fire Culture, Treatment Barriers, Practice Implications, and Research Directions. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2019, 51, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S.; Kirkman Sheryl Reimer, M.-E.J. Interpretive Description: A Noncategorical Qualitative Alternative for Developing Nursing Knowledge. Res. Nurs. Health 1997, 20, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S. Interpretive Description, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S. Scaffolding a Study. In Interpretive Description, 1st ed.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S.; Kirkham, S.R.; O’Flynn-Magee, K. The Analytic Challenge in Interpretive Description. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2004, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Qualitative Research in Psychology Using thematic analysis in psychology Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Turner, S.; El-Gabalawy, R.; Sareen, J.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Anxiety-related psychopathology and chronic pain comorbidity among public safety personnel. J. Anxiety Disord. 2018, 55, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermid, J.C.; Tang, K.; Sinden, K.E.; D’Amico, R. Work Functioning Among Firefighters: A Comparison Between Self-Reported Limitations and Functional Task Performance. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2019, 29, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, G.; MacDermid, J.C. Minimal Detectable Change Thresholds and Responsiveness of Zephyr Bioharness and Fitbit Charge Devices. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Facilitators | Barriers | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal |

|

|

| Quotes |

|

|

| Firefighter Work and Culture |

|

|

| Quotes |

|

|

| Firefighter-specific training and programs |

|

|

| Quotes |

|

|

| Firefighter Leadership/ Management |

|

|

| Quotes |

|

|

| Social Supports |

|

|

| Quotes |

|

|

| Health care |

|

|

| Quotes |

| |

| Societal attitudes and policies |

|

|

| Quotes |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

MacDermid, J.C.; Lomotan, M.; Hu, M.A. Canadian Career Firefighters’ Mental Health Impacts and Priorities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312666

MacDermid JC, Lomotan M, Hu MA. Canadian Career Firefighters’ Mental Health Impacts and Priorities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312666

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacDermid, Joy C., Margaret Lomotan, and Mostin A. Hu. 2021. "Canadian Career Firefighters’ Mental Health Impacts and Priorities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312666

APA StyleMacDermid, J. C., Lomotan, M., & Hu, M. A. (2021). Canadian Career Firefighters’ Mental Health Impacts and Priorities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312666