Implementing the Federal Smoke-Free Public Housing Policy in New York City: Understanding Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Policy Impact

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

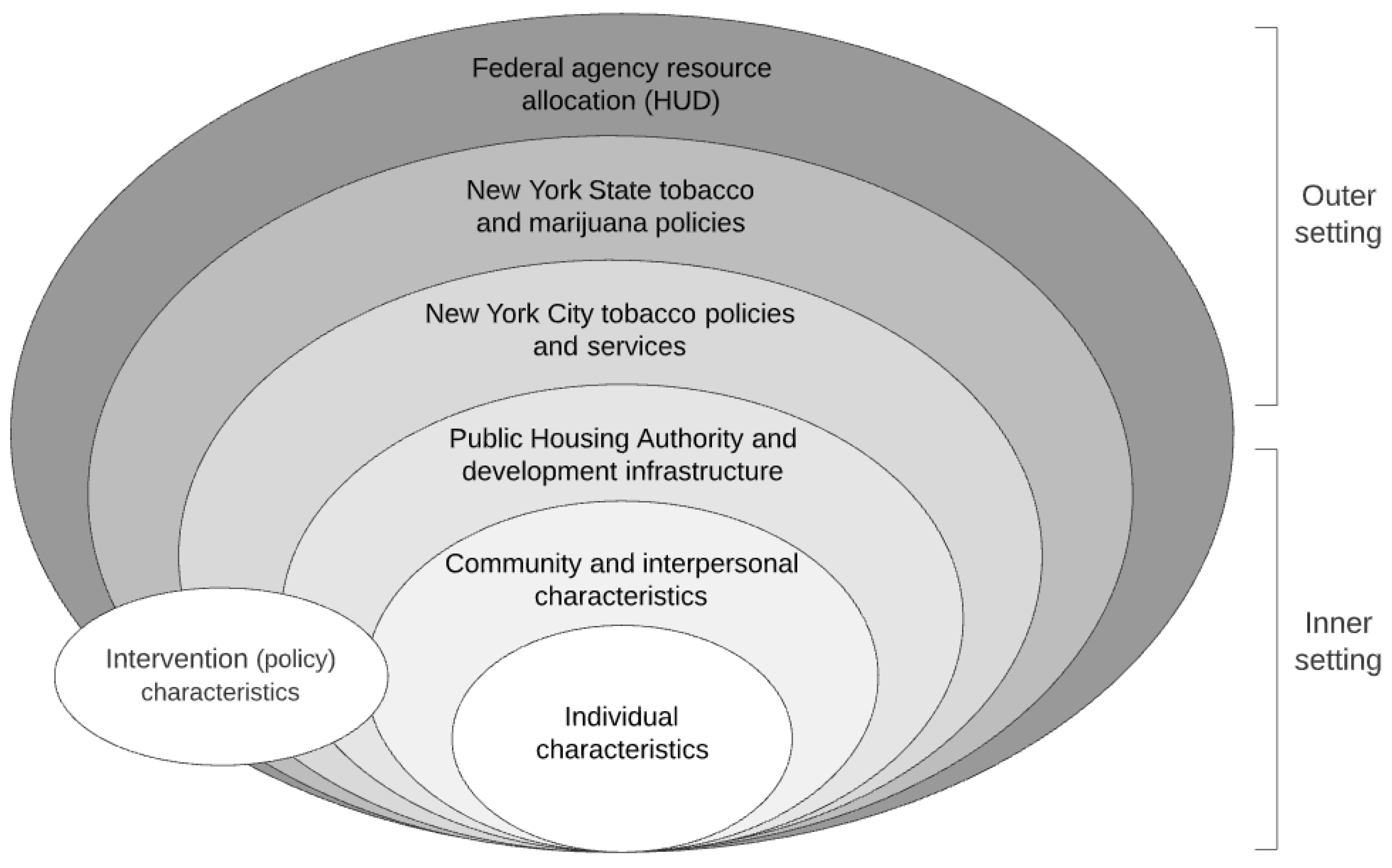

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Qualitative Data Collection

2.3. Resident Surveys

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Findings

3.1.1. Outer Setting

HUD Resources

PHA Partnerships

Marijuana Policy

3.1.2. Intervention Characteristics

3.1.3. Individual Characteristics

3.1.4. Inner Setting

Structural and Environmental Barriers

Interpersonal Safety Concerns

Community Cohesiveness

Lack of Smoking Cessation Support

Relative Priority of SFH Policy

Compatibility

3.1.5. Implementation Process

Planning and Community Engagement

Enforcement

3.1.6. Strategies for Improving SFH Policy Implementation

3.2. Survey Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2006.

- Bonetti, P.O.; Lardi, E.; Geissmann, C.; Kuhn, M.U.; Brüesch, H.; Reinhart, W.H. Effect of brief secondhand smoke exposure on endothelial function and circulating markers of inflammation. Atherosclerosis 2011, 215, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-I.; Burton, T.; Baker, C.L.; Mastey, V.; Mannino, D. Recent trends in exposure to secondhand smoke in the United States population. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Helms, V.E.; King, B.A.; Ashley, P.J. Cigarette smoking and adverse health outcomes among adults receiving federal housing assistance. Prev. Med. 2017, 99, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.A.; Peck, R.M.; Babb, S.D. National and state cost savings associated with prohibiting smoking in subsidized and public housing in the United States. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, 140222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, K.H.; Gomez, Y.; Homa, D.M.; King, B.A. Tobacco use, secondhand smoke, and smoke-free home rules in multiunit housing. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kraev, T.A.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Hammond, S.K.; Spengler, J.D. Indoor concentrations of nicotine in low-income, multi-unit housing: Associations with smoking behaviours and housing characteristics. Tob. Control. 2009, 18, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Martinez-Donate, A.P.; Jones, N.R. Educational disparities in home smoking bans among households with underage children in the United States: Can tobacco control policies help to narrow the gap? Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 15, 1978–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. HUD Secretary Castro Announces Public Housing to Be Smoke-Free 2016. Available online: https://www.hud.gov/press/press_releases_media_advisories/2016/HUDNo_16-184 (accessed on 2 November 2017).

- Snyder, K.; Vick, J.H.; King, B.A. Smoke-free multiunit housing: A review of the scientific literature. Tob. Control. 2015, 25, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Federal Rental Assistance Provides Affordable Homes for Vulnerable People in All Types of Communities Updated 9 November 2017. Available online: https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/federal-rental-assistance-provides-affordable-homes-for-vulnerable-people-in-all#appendix3 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Thorpe, L.E.; Anastasiou, E.; Wyka, K.; Tovar, A.; Gill, E.; Rule, A.; Elbel, B.; Kaplan, S.A.; Jiang, N.; Gordon, T.; et al. Evaluation of secondhand smoke exposure in New York City public housing after implementation of the 2018 federal smoke-free housing policy. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2024385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.E.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Rigotti, N.A.; Fang, S.C.; Winickoff, J.P. Changes in tobacco smoke exposure following the institution of a smoke-free policy in the Boston housing authority. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, W.; Karp, S.; Bialick, P.; Liverance, C.; Seder, A.; Berg, E.; Karp, L. Health, secondhand smoke exposure, and smoking behavior impacts of no-smoking policies in public housing, Colorado, 2014–2015. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, E148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klassen, A.C.; Lee, N.L.; Pankiewicz, A.; Ward, R.; Shuster, M.; Ogbenna, B.T.; Wade, A.; Boamah, M.; Osayameh, O.; Rule, A.M.; et al. Secondhand smoke exposure and smoke-free policy in Philadelphia Public Housing. Tob. Regul. Sci. 2017, 3, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plunk, A.D.; Rees, V.W.; Jeng, A.; Wray, J.A.; Grucza, R.A. Increases in secondhand smoke after going smoke-free: An assessment of the impact of a mandated smoke-free housing policy. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 2254–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNaughton, P.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Arku, R.E.; Vallarino, J.; Levy, D.E. The impact of a smoke-free policy on environmental tobacco smoke exposure in public housing developments. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 557–558, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández, D.; Swope, C.B.; Azuogu, C.; Siegel, E.; Giovenco, D.P. ‘If I pay rent, I’m gonna smoke’: Insights on the social contract of smokefree housing policy in affordable housing settings. Health Place 2019, 56, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, J.; Goldman, R.; Rees, V.W.; Frounfelker, R.L.; Davine, J.; Keske, R.R.; Brooks, D.R.; Geller, A.C. Qualitative assessment of smoke-free policy implementation in low-income housing: Enhancing resident compliance. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lane, H.; Porter, K.; Estabrooks, P.; Zoellner, J. A systematic review to assess sugar-sweetened beverage interventions for children and adolescents across the Socioecological Model. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cardozo, R.A.; Feinberg, A.; Tovar, A.; Vilcassim, M.J.R.; Shelley, D.; Elbel, B.; Kaplan, S.; Wyka, K.; Rule, A.M.; Gordon, T.; et al. A protocol for measuring the impact of a smoke-free housing policy on indoor tobacco smoke exposure. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silver, C.; Lewins, A. Using Software in Qualitative Research: A Step-by-Step Guide; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Byron, M.J.; Cohen, J.E.; Frattaroli, S.; Gittelsohn, J.; Drope, J.M.; Jernigan, D.H. Implementing smoke-free policies in low- and middle-income countries: A brief review and research agenda. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2019, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokicki, S.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Fang, S.C.; Rigotti, N.A.; Winickoff, J.P.; Levy, D.E. Assessment of residents’ attitudes and satisfaction before and after implementation of a smoke-free policy in Boston multiunit housing. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016, 18, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennrikus, D.J.; Widome, R.L.; Skahen, K.; Fabian, L.E.; Bonilla, Z.E. Resident reactions to smoke-free policy implementation in public housing. Tob. Regul. Sci. 2017, 3, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Thorpe, L.; Kaplan, S.; Shelley, D. Perceptions about the federally mandated smoke-free housing policy among residents living in public housing in New York City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drach, L.L.; Pizacani, B.A.; Rohde, K.L.; Schubert, S. The acceptability of comprehensive smoke-free policies to low-income tenants in subsidized housing. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2010, 7, A66. [Google Scholar]

- DiGiulio, A.; Jump, Z.; Babb, S.; Schecter, A.; Williams, K.-A.S.; Yembra, D.; Armour, B.S. State Medicaid coverage for tobacco cessation treatments and barriers to accessing treatments—United States, 2008–2018. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anastasiou, E.; Chennareddy, S.; Wyka, K.; Shelley, D.; Thorpe, L.E. Self-reported secondhand marijuana smoke (SHMS) exposure in two New York City (NYC) subsidized housing settings, 2018: NYC Housing Authority and lower-income private sector buildings. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oliver, K.; Lorenc, T.; Tinkler, J.; Bonell, C. Understanding the unintended consequences of public health policies: The views of policymakers and evaluators. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, J.; Birken, S.A.; Powell, B.J.; Rohweder, C.; Shea, C.M. Beyond “implementation strategies”: Classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, P.; Kang, J.; Kennedy, R.D.; Beck, P.; Ferrence, R. Impact of smoke-free housing policy lease exemptions on compliance, enforcement and smoking behavior: A qualitative study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 10, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Development 1 | Development 2 | Development 3 | Development 4 | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 8 | (40.0) | 2 | (12.5) | 2 | (22.2) | 2 | (11.1) | 14 | (21.9) |

| Female | 12 | (60.0) | 14 | (87.5) | 7 | (77.8) | 16 | (88.9) | 49 | (76.6) |

| Mean age, Year (SD) | 58.1 | (13.8) | 63.7 | (10.1) | 52.4 | (20.8) | 64.2 | (15.2) | 60.3 | (15.1) |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

| Current smoker | 10 | (50.0) | 7 | (43.8) | 5 | (55.6) | 4 | (21.1) | 26 | (40.6) |

| Non-current smoker | 10 | (50.0) | 9 | (56.3) | 4 | (44.4) | 15 | (78.9) | 38 | (59.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 3 | (18.8) | 1 | (6.3) | 2 | (22.2) | 11 | (61.1) | 17 | (26.6) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 6 | (37.5) | 15 | (93.8) | 7 | (77.8) | 5 | (27.8) | 33 | (51.6) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 5 | (31.3) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (11.1) | 7 | (10.9) |

| Asian | 1 | (6.3) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (11.1) | 3 | (4.7) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 | (18.8) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (4.7) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Less than high school | 4 | (20.0) | 2 | (12.5) | 1 | (11.1) | 2 | (10.5) | 9 | (14.1) |

| High school graduate | 4 | (20.0) | 8 | (50.0) | 4 | (44.4) | 7 | (36.8) | 23 | (35.9) |

| Greater than high school | 11 | (55.0) | 6 | (37.5) | 4 | (44.4) | 10 | (52.7) | 31 | (48.4) |

| Unreported | 1 | (5.0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (1.6) |

| Domains | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| Domain 1: Outer Setting | |

| PHA partnerships | “We’re going to be in the next year trying to think of new ways to partner with people who are both into health care and community space we will certainly work to integrate all the different, healthy-home topics around that, so smoke-free alongside with the pest management and the mold work” (Staff #2). |

| Marijuana policy | “If you’re going to ban smoking, you have to ban the people who are smoking marijuana. It’s permeating the house the same way” (Smoker, FG #6), “Y’all talking about cigarette smoke, [but] if somebody is smoking marijuana and it’s coming in my apartment,’ that’s not a problem”? (Nonsmoker, FG #1) “[Marijuana use] is blatantly in the open, and nobody cares anymore” (Staff #4). |

| Domain 2: Intervention characteristics | “I just don’t think no one could come in my house and tell me what to do, when I pay my rent” (Smoker, FG #2). “Each person has the right to do whatever they please. I can’t say anything to them about it” (Nonsmoker, FG #3). “People have rights. And you sort of invading their privacy when you tell a tenant you can’t smoke in your apartment” (Staff #5). |

| Domain 3: Individual characteristics | “That no-smoking policy is just another rule to set residents up for eviction” (Smoker, FG#2). “I think it’s unfair. You’re going to lose your apartment just because someone complained about cigarette smoke”? (Nonsmoker, FG #3). |

| Domain 4: Inner Setting | |

| Interpersonal safety concerns | “You’re creating an enemy when you start the reporting” (Nonsmoker, FG #3). “I wouldn’t dare ask somebody to not smoke” (Nonsmoker, FG #8). “[Staff] are told never, ever confront anybody, not for smoking or anything else” (Staff #5). |

| Structural and environmental barriers | “They are all close-knit buildings. To move 25 feet away from this one you’re only going back in front of this one. Right in front of the next one” (Smoker, FG #9). “I’m not going outside in a snow blizzard to smoke, and in the rain” (Smoker, FG #6). |

| Community cohesiveness | “Everybody’s been here for ages. Everybody knows each other, and pretty much respects each other” (Smoker, FG#2). “It’s basically every man for themselves. They [other residents] don’t even bother with rules” (Nonsmoker, FG #3). |

| Lack of smoking cessation services | “I think it would be helpful if they [PHA] started offering an onsite smoking cessation program” (Smoker, FG #9). “What would be nice if we can get a class for people or maybe go around to give out patches” (RA #3). |

| Relative priority of SFH policy | “They [PHA] should take some of that energy and enforce the policies that already put in place and leave us alone” (Smoker, FG #4). “You’re saying smoking? But there’re a lot of things inside the apartment that are not being dealt with as well” (Nonsmoker, FG #1). |

| Compatibility | “A lot of property managers feel like they’re overwhelmed, and this is just one more thing that they have to deal with” (Staff #2). |

| Domain 5: Implementation Process | |

| Planning and community engagement | “This [roll out] could have worked better and been a more positive experience for us had the PHA staff first come in and done this focus group before, and along with some smoking cessation” (Smoker, FG #4). “They could’ve made us more aware by providing more information. And make a list of pros of why you shouldn’t smoke in your apartment” (Smoker, FG #9). “Get out more information and more material to the people” (Nonsmoker, FG #8). |

| Enforcement | “Housing doesn’t enforce that policy” (Nonsmoker, FG #1). “Their [Housing’s] own employees walking in and out of the building with a cigarette in their mouth. Who are you to tell me not to smoke”? (Smoker, FG #6). “The housing staffs themselves smoke at the front. So why would they implement that rule, if they are the first ones to break it” (Nonsmoker, FG #7). “I’m not going to go into somebody’s house to see whether or not they’re smoking”. (Staff #4) |

| Pre-Launch (April–July 2018) N = 153 | Post-Launch (May–September 2019) N = 130 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Support for NYCHA SFH policy | 146 | (94.8) | 125 | (96.2) | 0.655 |

| Satisfaction with NYCHA’s introduction of SFH policy | 123 | (81.5) | 91 | (70.5) | 0.033 |

| Satisfaction with enforcement of SFH policy | 89 | (60.1) | 62 | (48.8) | 0.047 |

| Which of the following have you experienced in the past 6 months related to SFH policy? | |||||

| Saw signs, posters or other materials about the policy in building | 78 | (50.7) | 62 | (47.7) | 0.593 |

| Received an invitation or seen posters/flyers about meetings to discuss the policy | 54 | (36.1) | 24 | (18.5) | 0.001 |

| Attended resident meetings where this policy was discussed | 14 | (9.1) | 12 | (9.2) | 0.999 |

| Submitted a complaint about others smoking in the building | 22 | (14.3) | 28 | (21.5) | 0.170 |

| Complained directly to a smoker | 42 | (27.3) | 39 | (30.0) | 0.695 |

| Heard about new smoking cessation services available | 22 | (14.3) | 32 | (24.6) | 0.071 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, N.; Gill, E.; Thorpe, L.E.; Rogers, E.S.; de Leon, C.; Anastasiou, E.; Kaplan, S.A.; Shelley, D. Implementing the Federal Smoke-Free Public Housing Policy in New York City: Understanding Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Policy Impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312565

Jiang N, Gill E, Thorpe LE, Rogers ES, de Leon C, Anastasiou E, Kaplan SA, Shelley D. Implementing the Federal Smoke-Free Public Housing Policy in New York City: Understanding Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Policy Impact. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312565

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Nan, Emily Gill, Lorna E. Thorpe, Erin S. Rogers, Cora de Leon, Elle Anastasiou, Sue A. Kaplan, and Donna Shelley. 2021. "Implementing the Federal Smoke-Free Public Housing Policy in New York City: Understanding Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Policy Impact" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312565

APA StyleJiang, N., Gill, E., Thorpe, L. E., Rogers, E. S., de Leon, C., Anastasiou, E., Kaplan, S. A., & Shelley, D. (2021). Implementing the Federal Smoke-Free Public Housing Policy in New York City: Understanding Challenges and Opportunities for Improving Policy Impact. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312565