“With Enthusiasm and Energy throughout the Day”: Promoting a Physically Active Lifestyle in People with Intellectual Disability by Using a Participatory Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

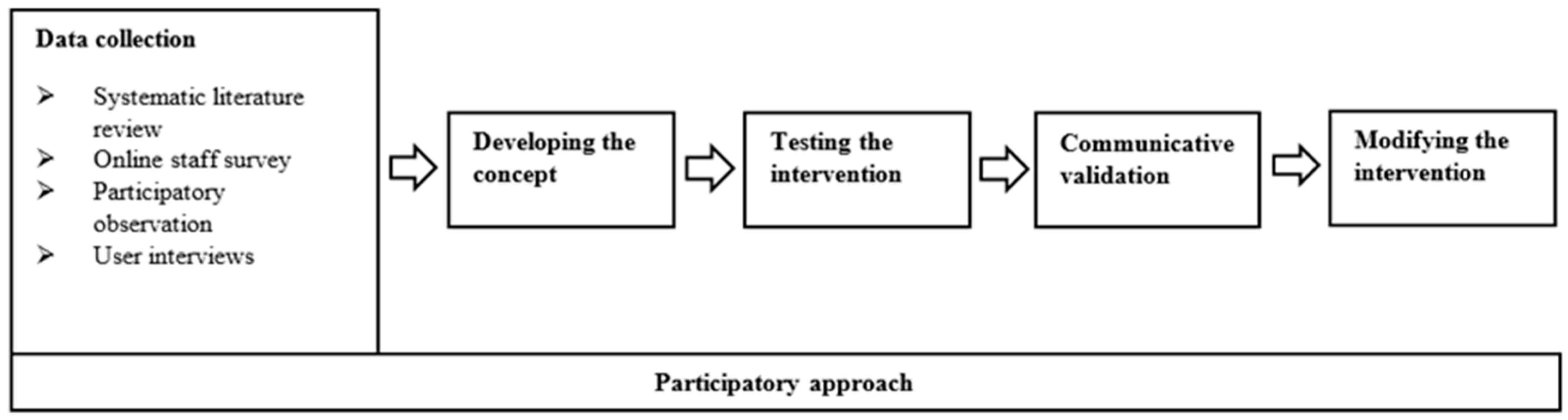

2. Participative Approach

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Interviews

3.1.1. Participant Recruitment

3.1.2. Interview Conduct and Analysis

3.1.3. Participatory Elements within Design of the Interview Guideline and the Situation Itself

3.2. Test of the Intervention and Communicative Validation

4. Interview Results

- -

- Interview results and implications for physical activity promoting concepts

- -

- Conceptualization of the intervention

- ⚬

- Implications of the user interviews

- ⚬

- Considering the theoretical background

- -

- The initial intervention concept

- -

- Testing and modifying the intervention

- -

- Content and structure of the final user manual

Interview Results and Implications for Physical Activity Promoting Concepts

5. Conceptualization of the Intervention

5.1. Implications from the User Interviews

5.2. Considering the Theoretical Background

5.3. The Initial Intervention Concept

6. Testing and Modifying the Intervention

6.1. Testing the Intervention

6.2. Content and Structure of the Final User Manual

7. Discussion

7.1. Comparisons with Other Projects

7.2. Challenges

7.3. Dynamics

7.4. Limitations

7.5. Distribution of the Intervention

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García-Domínguez, L.; Navas, P.; Verdugo, M.A.; Arias, V.B. Chronic Health Conditions in Aging Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Global Health Risks. Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44203 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Ding, D.; Lawson, K.D.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L.; Finkelstein, E.A.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; van Mechelen, W.; Pratt, M. The economic burden of physical inactivity: A global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2016, 388, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030. More Active People for a Healthier Word. Available online: Apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Dairo, Y.M.; Collett, J.; Dawes, H.; Oskrochi, G.R. Physical activity levels in adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Temple, V.A.; Frey, G.C.; Stanish, H.I. Interventions to promote physical activity for adults with intellectual disabilities. Salud Publica Mexico 2017, 59, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Definition: Intellectual Disability. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/de/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases/mental-health/news/news/2010/15/childrens-right-to-family-life/definition-intellectual-disability (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Emerson, E.; Hatton, C. Health Inequalities and People with Intellectual Disabilities; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stanish, H.I.; Frey, G.C. Promotion of physical activity in individuals with intellectual disability. Salud Publica Mexico 2008, 50, s178–s184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartlo, P.; Klein, P.J. Physical Activity Benefits and Needs in Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: Systematic Review of the Literature. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 116, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latteck, Ä.-D. Literatur- und Datenbankrecherche zu Gesundheitsförderungs- und Präventionsansätzen bei Menschen mit Behinderungen und der Auswertung der vorliegenden Evidenz. Ergebnisbericht; GKV-Spitzenverband: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nutsch, N.; Bruland, D.; Latteck, Ä.-D. Promoting physical activity in everyday life of people with intellectual disabilities. An intervention overview. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, M.; Waninge, A.; Hilgenkamp, T.I.M.; Van Empelen, P.; Krijnen, W.P.; Van Der Schans, C.P.; Melville, C.A. Effects of lifestyle change interventions for people with intellectual disabilities: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 31, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruland, D.; Schulenkorf, T.; Nutsch, N.; Nadolny, S.; Latteck, Ä.-D. Interventions to Improve Physical Activity in Daily Life of People with Intellectual Disabilities. Detailed Results Presentation of a Scoping Review. 2019. Available online: https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2939511 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- ICPHR (International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research). What Is Participatory Health Research (PHR)? Available online: http://www.icphr.org/ (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Buchner, T.; Koenig, O.; Schuppener, S. (Eds.) Inklusive Forschung. Gemeinsam mit Menschen mit Lernschwierigkeiten Forschen; Verlag Julius Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, K.; Offergeld, J.; Freymuth, N.; Arp, A.L.; Benz, B.; Schönig, W.; Walther, K. Gemeinsam Forschung Gestalten. Handreichung zu partizipativer Forschung; Sozial-Wissenschaftsladen: Bochum/Köln, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ICPHR (International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research). Position Paper 3: Impact in Participatory Health Research; International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, F.; Miggelbrink, J.; Beurskens, K. Yes, we can (?) Kommunikative Validierung in der qualitativen Forschung. In Ins Feld und zurück—Praktische Probleme qualitativer Forschung in der Sozialgeographiem; Meyer, F., Miggelbrink, J., Beurskens, K., Eds.; Springer Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, S. Bewegungsbezogene Gesundheitskompetenz (bGK). Die Vermittlung von bGK in der Lehre für eine qualitativ hochwertige Klientenversorgung. PADUA 2020, 15, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, I.; Bär, G. The Analysis of Qualitative Data with Peer Researchers: An Example from Participatory Health Research. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bruland, D.; Mauro, A.; Ising, C.; Major, J.; Latteck, Ä.-D. Förderung von Bewegungsfähigkeiten und körperlicher Aktivität von Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung: Partizipative Entwicklung und Erprobung der multimodalen Intervention “Mit Schwung und Energie durch den Tag”. In Förderung von Gesundheit und Partizipation bei chronischer Krankheit und Pflegebedürftigkeit im Lebensverlauf; Reihe Gesundheitsforschung; Hämel, K., Röhnsch, G., Eds.; BeltzJuventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bruland, D.; Mauro, A.; Vetter, N.S.; Latteck, Ä.D. Stärkung von Gesundheitskompetenz von Menschen mit geistiger Behinderung. Implikationen für die Gesundheitskompetenz aus einem Forschungsprojekt zur Förderung körperlicher Aktivität. In Gesundheitskompetenz; Rathmann, K., Dadaczynski, K., Okan, O., Messer, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2021; accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Carl, J.; Sudeck, G.; Pfeifer, K. Competencies for a Healthy Physically Active Lifestyle—Reflections on the Model of Physical Activity-Related Health Competence. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Unger, H. Partizipative Forschung; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, N.M.; Landorf, K.B.; Schields, N.; Munteanu, S.E. Effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity in individuals with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2019, 63, 168–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heller, T.; Sorensen, A. Promoting healthy aging in adults with developmental disabilities. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2013, 18, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinder, L.S.; Bergström, H.; Hagberg, J.; Wihlman, U.; Hagströmer, M. Promoting a healthy diet and physical activity in adults with intellectual disabilities living in community residences: Design and evaluation of a cluster-randomized intervention. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dixon-Ibarra, A.; Driver, S.; Van Volkenburg, H.; Humphries, K. Formative evaluation on a physical activity health promotion program for the group home setting. Eval. Program Plan. 2017, 60, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodde, A.E.; Seo, D.-C.; Frey, G.C.; Lohrmann, D.K.; Van Puymbroeck, M. Developing a Physical Activity Education Curriculum for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities. Health Promot. Pract. 2011, 13, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, A.T.; Zeldin, A.S.; Shihady Diab, I.R.; Garro, N.M.; Allevato, N.A.; Lehrer, D.; WRC Project Oversight Team. The Healthy Lifestyle Change Program. A pilot of a community-based health promotion intervention for adults with develop-mental disabilities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, L.; Mitchell, F.; Stalker, K.; McConnachie, A.; Murray, H.; Melling, C.; Mutrie, N.; Melville, C. Process evaluation of the Walk Well study: A cluster-randomised controlled trial of a community based walking programme for adults with intellectual disabilities. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tacke, D.; Tiesmeyer, K.; Latteck, Ä.-D.; Fornefeld, B. „Teilhabe ist durch Gesetze allein nicht erreichbar!”. Menschen mit Komplexer Behinderung sollten in Forschung einbezogen sein! Teilhabe 2019, 58, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Liebel, A.M. What Counts as Literacy in Health Literacy: Applying the Autonomous and Ideological Models of Literacy. Lit. Compos. Stud. 2021, 8, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, P. “Health literacy is linked to literacy”: Eine Betrachtung der im Forschungsdiskurs zu Health Literacy berücksichtigten und unberücksichtigten Beiträge aus der Literacy Forschung. In Health Literacy im Kindes- und Jugendalter; Bollweg, T., Bröder, J., Pinheiro, P., Eds.; Gesundheit und Gesellschaft; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 393–415. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cruzado, D.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.I. Changes on quality of life, self-efficacy and social support for activities and physical fitness in people with intellectual disabilities through multimodal intervention. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2016, 31, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex | 15 Female | 9 Male |

|---|---|---|

| Living area | 20 outpatient | 4 inpatient |

| Age | 21–68 years of age, mean age 44 years | |

| Work area | 2 retired persons, 1 person working in regular labor market, 21 persons working in workshops for disabled persons | |

| Categories and Subcategories | Implications | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual factors | Physical and cognitive cognitions | Diversity of cognitive and physical limitations and support needs have to be considered by offering flexible and adaptable approaches. | |

| Physical activity related knowledge | Basics of physical activity-related knowledge (including distinguishing types of physical activity) have to be provided. | ||

| Psychological factors | Physical activity related experiences and associations | It should be built upon positive experiences/these should be created. Heterogeneous physical activity-related experiences and preferences should be addressed. | |

| Self-management strategies for being physically active | Strengthening of self-management strategies is needed for dealing with internal and external obstacles. | ||

| Contextual factors | Social factors | Social support | In many cases, support from another person is indicated and/or desired. Addressing different user needs and preferences. |

| Environmental factors | Tight day structure | Exercise in everyday life should be promoted. | |

| Physical activity programs | Low-threshold access is needed (considering the living environment rather than creating new programs). | ||

| Barrier-free environments | Environmental conditions in the context of individual physical conditions have to be considered. | ||

| Weather conditions | Promotion of self-management strategies is suggested. | ||

| Topic | Negative Feedback | Positive Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation process |

| |

| Structural design (instructions, structure, materials, comprehensibility, language used, pictures) |

|

|

| Content (are topics covered that are considered important, adequately described, are desired topics missing?) |

|

|

| Feasibility of implementation (e.g., target group specific/fit for client/over-demanding, supervision necessary) |

|

|

| Assumptions of effect & sustainability |

|

|

| User Manual | |

|---|---|

| Modules | Units |

| Introduction and overview |

| 1. Physical activity buddy | |

| 2. Physical activity passport | |

| 3. What is physical activity? |

| 4. Why is it important? | |

| 5. How can I be active in everyday life? | |

| 6. Physical activity and health | |

| 7. How much should I do? | |

| 8. Physical activity related goals |

| 9. Observation sheet | |

| 10. Self-reflection |

| 11. Meeting barriers | |

| 12. How to proceed? | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mauro, A.; Bruland, D.; Latteck, Ä.-D. “With Enthusiasm and Energy throughout the Day”: Promoting a Physically Active Lifestyle in People with Intellectual Disability by Using a Participatory Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312329

Mauro A, Bruland D, Latteck Ä-D. “With Enthusiasm and Energy throughout the Day”: Promoting a Physically Active Lifestyle in People with Intellectual Disability by Using a Participatory Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312329

Chicago/Turabian StyleMauro, Antonia, Dirk Bruland, and Änne-Dörte Latteck. 2021. "“With Enthusiasm and Energy throughout the Day”: Promoting a Physically Active Lifestyle in People with Intellectual Disability by Using a Participatory Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312329

APA StyleMauro, A., Bruland, D., & Latteck, Ä.-D. (2021). “With Enthusiasm and Energy throughout the Day”: Promoting a Physically Active Lifestyle in People with Intellectual Disability by Using a Participatory Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312329