Do State Comprehensive Planning Statutes Address Physical Activity?: Implications for Rural Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. State Statute Identification and Coding Protocol

2.2. State Statute Variables

2.2.1. Required or Encouraged Items Related to PA

2.2.2. Primary Elements, Subsumed Elements, and Topics

2.2.3. Conditional Mandates

2.3. State-Level Rurality

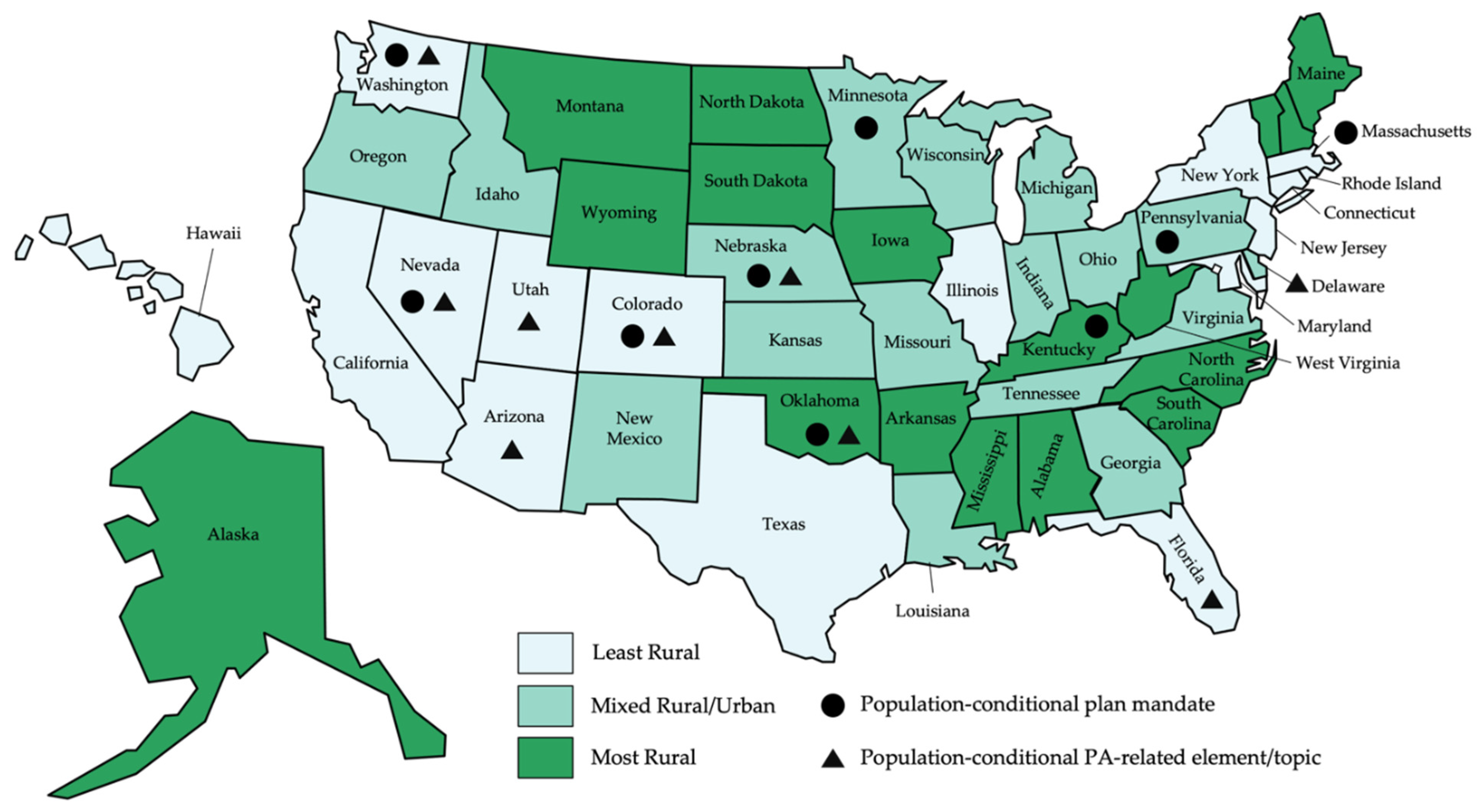

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Requirements and Encouragement for Items Related to PA

3.2. Differing Comprehensive Planning Mandates Based on Local-Level Rurality

3.3. Differences in PA-Related Elements and Topics Based on State-Level Rurality

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings

4.1.1. PA-Related Items in State Statutes

4.1.2. Comprehensive Planning and PA-Related Items by State- and Local-Level Rurality

4.1.3. PA Language in State Statutes

- (A)

- Identify objectives and policies to reduce the unique or compounded health risks in disadvantaged communities by means that include, but are not limited to, the reduction of pollution exposure, including the improvement of air quality, and the promotion of public facilities, food access, safe and sanitary homes, and physical activity” [73].

4.2. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Coded Language |

|---|---|

| Transportation | |

| Bicycle/Pedestrian |

|

| Bicycling |

|

| Pedestrian |

|

| Public transportation |

|

| Streets |

|

| Transportation/Circulation |

|

| Land Use | |

| Land use |

|

| Design |

|

| Infill/Reuse |

|

| Mixed use |

|

| Smart growth |

|

| Farmland preservation |

|

| Historic preservation |

|

| Parks & Recreation | |

| Parks/Recreation |

|

| Open space |

|

| Trails |

|

| Natural resources |

|

| Other Relevant | |

| Physical activity |

|

| Equity |

|

Appendix B

| State | Conditions for Planning Mandates | Conditions for Elements/Topics |

|---|---|---|

| Least Rural | ||

| Arizona |

| |

| Colorado |

|

|

| Florida |

| |

| Massachusetts |

| |

| Nevada |

|

|

| Utah |

| |

| Washington |

|

|

| Mixed Rural/Urban | ||

| Delaware |

| |

| Minnesota |

| |

| Nebraska |

|

|

| Pennsylvania |

| |

| Most Rural | ||

| Kentucky |

| |

| Oklahoma |

|

|

References

- McDowell, C.P.; Dishman, R.K.; Gordon, B.R.; Herring, M.P. Physical Activity and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelen, L.; Gale, J.; Chau, J.Y.; Hardy, L.L.; Mackey, M.; Johnson, N.; Shirley, D.; Bauman, A. Who Is at Risk of Chronic Disease? Associations between Risk Profiles of Physical Activity, Sitting and Cardio-Metabolic Disease in Australian Adults. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-H.; Chiang, S.-L.; Yates, P.; Lee, M.-S.; Hung, Y.-J.; Tzeng, W.-C.; Chiang, L.-C. Moderate Physical Activity Level as a Protective Factor against Metabolic Syndrome in Middle-Aged and Older Women. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/index.html (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Whitfield, G.P. Trends in Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines among Urban and Rural Dwelling Adults—United States, 2008–2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, A.S.; Chan, W.; Ng, J.Y.Y. Relation between Perceived Barrier Profiles, Physical Literacy, Motivation and Physical Activity Behaviors among Parents with a Young Child. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, J.A.; Lilly, C.L.; Leary, J.M.; Meeteer, W.; Campbell, H.D.; Dino, G.A.; Cotrell, L. Barriers to Parent Support for Physical Activity in Appalachia. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Spiteri, K.; Broom, D.; Bekhet, A.H.; de Caro, J.X.; Laventure, B.; Grafton, K. Barriers and Motivators of Physical Activity Participation in Middle-Aged and Older Adults—A Systematic Review. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 929–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chriqui, J.F.; Leider, J.; Thrun, E.; Nicholson, L.M.; Slater, S.J. Pedestrian-Oriented Zoning Is Associated with Reduced Income and Poverty Disparities in Adult Active Travel to Work, United States. Prev. Med. 2017, 95, S126–S133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Hosking, J.; Woodward, A.; Witten, K.; MacMillan, A.; Field, A.; Baas, P.; Mackie, H. Systematic Literature Review of Built Environment Effects on Physical Activity and Active Transport—An Update and New Findings on Health Equity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cervero, R.B.; Ascher, W.; Henderson, K.A.; Kraft, M.K.; Kerr, J. An Ecological Approach to Creating Active Living Communities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Vernez-Moudon, A.; Reis, R.; Turrell, G.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Badland, H.; Foster, S.; Lowe, M.; Sallis, J.F.; Stevenson, M.; et al. City Planning and Population Health: A Global Challenge. Lancet 2016, 388, 2912–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, E.; Simos, J. (Eds.) Healthy Cities: The Theory, Policy, and Practice of Value-Based Urban Planning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4939-6692-9. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. More Active People for a Healthier World: Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018-2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-92-4-151418-7. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Towards More Physical Activity in Cities: Transforming Public Spaces to Promote Physical Activity—A Key Contributor to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in Europe; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Salvo, D.; Garcia, L.; Reis, R.S.; Stankov, I.; Goel, R.; Schipperijn, J.; Hallal, P.C.; Ding, D.; Pratt, M. Physical Activity Promotion and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Building Synergies to Maximize Impact. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Lee, M.; Lee, J.; Kang, D.; Choi, J.-Y. Correlates Associated with Participation in Physical Activity among Adults: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Update. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärmeniemi, M.; Lankila, T.; Ikäheimo, T.; Koivumaa-Honkanen, H.; Korpelainen, R. The Built Environment as a Determinant of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies and Natural Experiments. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Community Preventative Services Task Force. Physical Activity: Built Environment Approaches Combining Transportation System Interventions with Land Use and Environmental Design; Community Preventative Services Task Force: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stankov, I.; Garcia, L.M.T.; Mascolli, M.A.; Montes, F.; Meisel, J.D.; Gouveia, N.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Hammond, R.A.; Caiaffa, W.T.; et al. A Systematic Review of Empirical and Simulation Studies Evaluating the Health Impact of Transportation Interventions. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, H.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M.; Timperio, A.; Foster, S. The Influence of the Built Environment, Social Environment and Health Behaviors on Body Mass Index. Results from RESIDE. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.Y.; Umstattd Meyer, M.R.; Lenardson, J.D.; Hartley, D. Built Environments and Active Living in Rural and Remote Areas: A Review of the Literature. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015, 4, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, E.; Kraak, V.I.; Hyatt, R.R.; Bloom, J.; Fenton, M.; Wagoner, C.; Economos, C.D. Active Living for Rural Children: Community Perspectives Using Photovoice. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefian, A.; Ziller, E.; Swartz, J.; Hartley, D. Active Living for Rural Youth: Addressing Physical Inactivity in Rural Communities. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2009, 15, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin, R.; Connor, L.; Nelson, M.; LaCroix, A.; Eldridge, G. Understanding Barriers and Facilitators to Healthy Eating and Active Living in Rural Communities. J. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanave, K.; Gabbert, K.; Tompkins, N.O.; Murphy, E.; Elliott, E.; Zizzi, S. Environmental Factors Affecting Rural Physical Activity Behaviors: Learning from Community Partners. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2021, 15, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umstattd Meyer, M.R.; Moore, J.B.; Abildso, C.; Edwards, M.B.; Gamble, A.; Baskin, M.L. Rural Active Living: A Call to Action. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2016, 22, E11–E20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godschalk, D.R.; Rouse, D.C. Sustaining Places: Best Practices for Comprehensive Plans; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, R.K. Using Content Analysis to Evaluate Local Master Plans and Zoning Codes. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 432–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyles, W.; Berke, P.; Smith, G. Local Plan Implementation: Assessing Conformance and Influence of Local Plans in the United States. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2016, 43, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, S.C.; Grădinaru, S.R. The Quality and Implementation of Local Plans: An Integrated Evaluation. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Wong, B. Toolkit to Integrate Health and Equity into Comprehensive Plans; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ricklin, A.; Klein, W.; Musiol, E. Healthy Planning: An Evaluation of Comprehensive and Sustainability Plans Addressing Public Health; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- American Planning Association. Survey of State Land Use and Natural Hazard Laws; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, E.J.; Bragar, J. Recent Developments in Comprehensive Planning. Urban Lawyer 2014, 46, 685–702. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, K. Comprehensive Planning for Public Health: Results of the Planning and Community Health Research Center Study; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, E.L.; Carlson, S.A.; Schmid, T.L.; Brown, D.R. Prevalence of Master Plans Supportive of Active Living in US Municipalities. Prev. Med. 2018, 115, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Aytur, S.A.; Satinsky, S.B.; Kerr, Z.Y.; Rodríguez, D.A. Planning for Pedestrians and Bicyclists: Results from a Statewide Municipal Survey. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, S275–S284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.L.; Carlson, S.A.; Schmid, T.L.; Brown, D.R.; Galuska, D.A. Supporting Active Living through Community Plans: The Association of Planning Documents with Design Standards and Features. Am J Health Promot 2019, 33, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytur, S.A.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Evenson, K.R.; Catellier, D.J.; Rosamond, W.D. The Sociodemographics of Land Use Planning: Relationships to Physical Activity, Accessibility, and Equity. Health Place 2008, 14, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chriqui, J.F.; Nicholson, L.M.; Thrun, E.; Leider, J.; Slater, S.J. More Active Living-Oriented County and Municipal Zoning Is Associated with Increased Adult Leisure Time Physical Activity--United States, 2011. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, L.M.; Leider, J.; Chriqui, J.F. Exploring the Linkage between Activity-Friendly Zoning, Inactivity, and Cancer Incidence in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017, 26, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leider, J.; Chriqui, J.F.; Thrun, E. Associations between Active Living-Oriented Zoning and No Adult Leisure-Time Physical Activity in the U.S. Prev. Med. 2017, 95, S120–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chriqui, J.F.; Leider, J.; Thrun, E.; Nicholson, L.M.; Slater, S. Communities on the Move: Pedestrian-Oriented Zoning as a Facilitator of Adult Active Travel to Work in the United States. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrun, E.; Leider, J.; Chriqui, J.F. Exploring the Cross-Sectional Association between Transit-Oriented Development Zoning and Active Travel and Transit Usage in the United States, 2010–2014. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meck, S. Model Planning and Zoning Enabling Legislation: A Short History. In Modernizing State Planning Statutes: The Growing Smart Working Paper Series, Volume One; The Growing Smart Working Paper Series; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996; Volume 1, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Meck, S. Growing Smart Legislative Guidebook: Model Statutes for Planning and the Management of Change; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- American Law Institute. Model Land Development Code; American Law Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, P.R.; French, S.P. The Influence of State Planning Mandates on Local Plan Quality. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1994, 13, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.R.; Roenigk, D.J.; Kaiser, E.; Burby, R. Enhancing Plan Quality: Evaluating the Role of State Planning Mandates for Natural Hazard Mitigation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1996, 39, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meck, S.; Retzlaff, R.; Schwab, J. Regional Approaches to Affordable Housing; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Mersky, R.M.; Dunn, D.J.; Nelson, M.A.; Nelson, M.A.; Jacobstein, J.M. Fundamentals of Legal Research, 8th ed.; University Textbook Series; Foundation Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1-58778-064-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.L. Legal Research in a Nutshell, 6th ed.; West Pub. Co.: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-314-09589-3. [Google Scholar]

- LexisNexis. Available online: https://www.lexisnexis.com/en-us/gateway.page (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Burris, S.; Hitchcock, L.; Ibrahim, J.; Penn, M.; Ramanathan, T. Policy Surveillance: A Vital Public Health Practice Comes of Age. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2016, 41, 1151–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiden, K.M.; Kaplan, M.; Walling, L.A.; Miller, P.P.; Crist, G. A Comprehensive Scoring System to Measure Healthy Community Design in Land Use Plans and Regulations. Prev. Med. 2017, 95, S141–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, L.M.; Joyner, H.R.; LaGro, J.; Gilchrist Walker, J. Research Note: Development of a Comprehensive Plan Scorecard for Healthy, Active Rural Communities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 190, 103582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. Available online: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/ua/urban-rural-2010.html (accessed on 23 July 2018).

- McDonald, J.H. Handbook of Biological Statistics, 2nd ed.; Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jerrett, M.; Almanza, E.; Davies, M.; Wolch, J.; Dunton, G.; Spruitj-Metz, D.; Ann Pentz, M. Smart Growth Community Design and Physical Activity in Children. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 45, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, G.R.; Shiell, A. In Search of Causality: A Systematic Review of the Relationship between the Built Environment and Physical Activity among Adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umstattd Meyer, M.R.; Perry, C.K.; Sumrall, J.C.; Patterson, M.S.; Walsh, S.M.; Clendennen, S.C.; Hooker, S.P.; Evenson, K.R.; Goins, K.V.; Heinrich, K.M.; et al. Physical Activity–Related Policy and Environmental Strategies to Prevent Obesity in Rural Communities: A Systematic Review of the Literature, 2002–2013. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, 150406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzhugh, E.C.; Bassett, D.R.; Evans, M.F. Urban Trails and Physical Activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winig, B.D.; Wooten, H.; Allbee, A. Building in Healthy Infill; ChangeLab Solutions: Oakland, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, S.; Anderson, A.; Kline, S.; Brundage, V. Putting Transit to Work in Main Street America: How Smaller Cities and Rural Places Are Using Transit and Mobility Investments to Strengthen Their Economies and Communities 2012. Available online: http://www.reconnectingamerica.org/assets/PDFs/201205ruralfinal.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2018).

- Smith, A.S.; Trevelyan, E. The Older Population in Rural America: 2012–2016; American Community Survey Reports; U.S. Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Mishkovsky, N.; Dalbey, M.; Bertaina, S.; Read, A.; McGalliard, T. Putting Smart Growth to Work in Rural Communities; International City/County Management Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.; Eyler, A.A.; Tabak, R.G.; Valko, C.; Brownson, R.C. Opportunities for Promoting Physical Activity in Rural Communities by Understanding the Interests and Values of Community Members. J. Environ. Public Health 2017, 2017, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, K.A.; Croft, J.B.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Kanny, D.; Wheaton, A.G.; Cunningham, T.J.; Khan, L.K.; Caraballo, R.S.; Holt, J.B.; et al. Health-Related Behaviors by Urban-Rural County Classification—United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnidge, E.K.; Radvanyi, C.; Duggan, K.; Motton, F.; Wiggs, I.; Baker, E.A.; Brownson, R.C. Understanding and Addressing Barriers to Implementation of Environmental and Policy Interventions to Support Physical Activity and Healthy Eating in Rural Communities: Barriers to Environmental and Policy Interventions. J. Rural Health 2013, 29, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, J.; Keyes, S.D. The Promise of Wisconsin’s 1999 Comprehensive Planning Law: Land-Use Policy Reforms to Support Active Living. J. Health Polit Policy Law 2008, 33, 455–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authority and Scope of General Plans. Cal. Gov. Code § 65302. Available online: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=GOV§ionNum=65302 (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Comprehensive Plans—Mandatory elements. Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 36.70A.070. Available online: https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=36.70a.070 (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Presley, D.; Reinstein, T.; Burris, S. Resources for Policy Surveillance: A Report Prepared for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Law Program; Temple University Beasley School of Law: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Burby, R.J.; Dalton, L.C. Plans Can Matter! The Role of Land Use Plans and State Planning Mandates in Limiting the Development of Hazardous Areas. Public Adm. Rev. 1994, 54, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Spoon, C.; Cavill, N.; Engelberg, J.K.; Gebel, K.; Parker, M.; Thornton, C.M.; Lou, D.; Wilson, A.L.; Cutter, C.L.; et al. Co-Benefits of Designing Communities for Active Living: An Exploration of Literature. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PA-Related Item | Addressed | Mandated | Conditionally Mandated | Encouraged | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Transportation | ||||||||

| Transportation/Circulation | 40 | 80 | 25 | 50 | 12 | 24 | 3 | 6 |

| Streets | 37 | 74 | 22 | 44 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 24 |

| Public transportation | 23 | 46 | 7 | 14 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 20 |

| Bicycling | 11 | 22 | 6 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Pedestrian | 9 | 18 | 6 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Bicycle/Pedestrian | 7 | 14 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Land Use & Design | ||||||||

| Land use | 44 | 88 | 32 | 64 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 18 |

| Historic preservation | 21 | 42 | 11 | 22 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| Farmland preservation | 16 | 32 | 7 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 18 |

| Design | 13 | 26 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 14 |

| Infill/Reuse | 8 | 16 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Mixed use | 8 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Smart growth | 4 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Parks & Recreation | ||||||||

| Parks/Recreation | 45 | 90 | 23 | 46 | 5 | 10 | 17 | 34 |

| Natural resources | 37 | 74 | 19 | 38 | 5 | 10 | 13 | 26 |

| Open space | 30 | 60 | 16 | 32 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 18 |

| Trails | 10 | 20 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| Other Relevant | ||||||||

| Equity † | 31 | 62 | 15 | 30 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 20 |

| Physical activity | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| PA-Related Item | Primary Element | Subsumed Element | Topic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Transportation | ||||||

| Transportation/Circulation | 27 | 54 | 14 | 28 | 13 | 26 |

| Streets | 4 | 8 | 23 | 46 | 16 | 32 |

| Public transportation | 1 | 2 | 20 | 40 | 3 | 6 |

| Bicycling | 1 | 2 | 11 | 22 | 1 | 2 |

| Pedestrian | 0 | 0 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 4 |

| Bicycle/Pedestrian | 0 | 0 | 7 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Land Use & Design | ||||||

| Land use | 36 | 72 | 9 | 18 | 11 | 22 |

| Historic preservation | 9 | 18 | 11 | 22 | 6 | 12 |

| Design | 4 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 8 |

| Farmland preservation | 3 | 6 | 9 | 18 | 5 | 10 |

| Infill/Reuse | 1 | 2 | 7 | 14 | 1 | 2 |

| Smart growth | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Mixed use | 0 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 2 | 4 |

| Parks & Recreation | ||||||

| Natural resources | 22 | 44 | 20 | 40 | 14 | 28 |

| Parks/Recreation | 11 | 22 | 29 | 58 | 20 | 40 |

| Open space | 7 | 14 | 18 | 36 | 12 | 24 |

| Trails | 0 | 0 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 4 |

| Other Relevant | ||||||

| Equity † | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 22 |

| Physical activity | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| PA-Related Item | # of States with Population-Conditional Mandate on Item | # of States that Address Item 1 | % of States that Address Item that Have a Population-Conditional Mandate for Item 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation | |||

| Transportation/Circulation | 5 | 40 | 12.5 |

| Streets | 5 | 37 | 13.5 |

| Public transportation | 3 | 23 | 13.0 |

| Bicycling | 2 | 11 | 18.2 |

| Bicycle/Pedestrian | 2 | 7 | 28.6 |

| Pedestrian | 0 | 9 | 0.0 |

| Land Use & Design | |||

| Land Use | 6 | 44 | 13.6 |

| Historic preservation | 3 | 21 | 14.3 |

| Mixed use | 2 | 8 | 25.0 |

| Design | 2 | 13 | 15.4 |

| Smart growth | 1 | 4 | 25.0 |

| Farmland preservation | 0 | 16 | 0.0 |

| Infill/Reuse | 0 | 8 | 0.0 |

| Parks & Recreation | |||

| Parks/Recreation | 7 | 45 | 15.6 |

| Open space | 6 | 30 | 20.0 |

| Natural resources | 5 | 37 | 13.5 |

| Trails | 2 | 10 | 20.0 |

| Other Relevant | |||

| Equity † | 5 | 31 | 16.1 |

| Physical activity | 0 | 2 | 0.0 |

| State-Level Rurality 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA-Related Item | Least Rural (n = 16) | Mixed Rural/Urban (n = 17) | Most Rural (n = 17) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | Fisher’s Exact 2 p-Value | |

| Transportation | |||||||

| Transportation/Circulation | 16 | 100.0 | 12 | 70.6 | 12 | 70.6 | 0.038 |

| Streets | 12 | 75.0 | 13 | 76.5 | 12 | 70.6 | 1.000 |

| Public transportation | 11 | 68.8 | 7 | 41.2 | 5 | 29.4 | 0.074 |

| Bicycling | 5 | 31.3 | 4 | 23.5 | 2 | 11.8 | 0.401 |

| Pedestrian | 5 | 31.3 | 3 | 17.7 | 1 | 5.9 | 0.154 |

| Bicycle/Pedestrian | 4 | 25.0 | 1 | 5.9 | 2 | 11.8 | 0.269 |

| Land Use & Design | |||||||

| Land use | 16 | 100.0 | 13 | 76.5 | 15 | 88.2 | 0.145 |

| Historic preservation | 8 | 50.0 | 6 | 35.3 | 7 | 41.2 | 0.721 |

| Farmland preservation | 7 | 43.8 | 5 | 29.4 | 4 | 23.5 | 0.478 |

| Mixed use | 7 | 43.8 | 1 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.001 |

| Design | 6 | 37.5 | 3 | 17.7 | 4 | 23.5 | 0.436 |

| Infill/Reuse | 6 | 37.5 | 1 | 5.9 | 1 | 5.9 | 0.023 |

| Smart growth | 4 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.008 |

| Parks & Recreation | |||||||

| Parks/Recreation | 14 | 87.5 | 15 | 88.2 | 16 | 94.1 | 0.860 |

| Natural resources | 14 | 87.5 | 12 | 70.6 | 11 | 64.7 | 0.363 |

| Open space | 12 | 75.0 | 7 | 41.2 | 11 | 64.7 | 0.141 |

| Trails | 5 | 31.3 | 1 | 5.9 | 4 | 23.5 | 0.170 |

| Other Relevant | |||||||

| Equity † | 13 | 81.3 | 10 | 58.8 | 8 | 47.1 | 0.144 |

| Physical activity | 2 | 8.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.098 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charron, L.M.; Milstein, C.; Moyers, S.I.; Abildso, C.G.; Chriqui, J.F. Do State Comprehensive Planning Statutes Address Physical Activity?: Implications for Rural Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12190. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212190

Charron LM, Milstein C, Moyers SI, Abildso CG, Chriqui JF. Do State Comprehensive Planning Statutes Address Physical Activity?: Implications for Rural Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):12190. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212190

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharron, Lisa M., Chloe Milstein, Samantha I. Moyers, Christiaan G. Abildso, and Jamie F. Chriqui. 2021. "Do State Comprehensive Planning Statutes Address Physical Activity?: Implications for Rural Communities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 12190. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212190

APA StyleCharron, L. M., Milstein, C., Moyers, S. I., Abildso, C. G., & Chriqui, J. F. (2021). Do State Comprehensive Planning Statutes Address Physical Activity?: Implications for Rural Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12190. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212190