Abstract

Background: Several empirical studies have shown an association between informal caregiving for adults and loneliness or social isolation. Nevertheless, a systematic review is lacking synthesizing studies which have investigated these aforementioned associations. Therefore, our purpose was to give an overview of the existing evidence from observational studies. Materials and Methods: Three electronic databases (Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL) were searched in June 2021. Observational studies investigating the association between informal caregiving for adults and loneliness or social isolation were included. In contrast, studies examining grandchild care or private care for chronically ill children were excluded. Data extractions covered study design, assessment of informal caregiving, loneliness and social isolation, the characteristics of the sample, the analytical approach and key findings. Study quality was assessed based on the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Each step (study selection, data extraction and evaluation of study quality) was conducted by two reviewers. Results: In sum, twelve studies were included in our review (seven cross-sectional studies and five longitudinal studies)—all included studies were either from North America or Europe. The studies mainly showed an association between providing informal care and higher loneliness levels. The overall study quality was fair to good. Conclusion: Our systematic review mainly identified associations between providing informal care and higher loneliness levels. This is of great importance in assisting informal caregivers in avoiding loneliness, since it is associated with subsequent morbidity and mortality. Moreover, high loneliness levels of informal caregivers may have adverse consequences for informal care recipients.

1. Introduction

Remaining in familiar environments is often important for individuals in late life [1,2]. Therefore, home care is often preferred [3,4]. As the number of individuals needing care is likely to increase due to reasons of demographic ageing, home care is of great importance.

A key part of home care is the provision of informal care. This can be defined as the provision of private care for relatives, friends or neighbors in frequent need of care, including tasks such as personal care or simply assistance with the household [5]. A large body of evidence exists clearly demonstrating an association between informal caregiving and adverse health outcomes (such as decreased mental health, e.g., [6,7,8]).

Drawing on the caregiver stress model proposed by Pearlin et al. [9], informal caregiving can include several stressors such as burden [10]. These stressors can contribute to feelings of social isolation or loneliness [11]. Some studies have examined loneliness or social isolation in informal caregivers (e.g., [12,13,14,15]), partly demonstrating a link between provision of informal care and increased loneliness. This is plausible given the fact that informal caregiving can reduce the time available for family and friends due to reasons of prioritizing [16]—which can result in loneliness or isolation. Nevertheless, informal caregiving can also contribute to an increased size of social networks (e.g., by establishing contacts with other informal caregivers) and may therefore reduce feelings of loneliness or social isolation. Since a systematic review systematically synthesizing evidence regarding the association between informal caregiving (provided for adults) and loneliness or social isolation based on observational studies is lacking, our aim was to fill this gap in knowledge. Knowledge about this association may help to reduce these factors—which in turn, is of relevance since they are associated with several chronic illnesses, decreased perceived life expectancy [17,18] and reduced actual longevity [19,20].

It should be noted that loneliness and social isolation are related but distinct concepts [21]. For example, previous research showed a Pearson correlation of about five between loneliness and perceived social isolation [17]. While loneliness refers to the feeling that one’s social network is of a poorer quality or is smaller than desired [22,23], perceived social isolation refers to the feeling that one does not belong to society [22,23]. They also differ in their correlates and consequences (for further details, please see [17]). Both have in common the fact that they refer to social needs [24].

2. Methods

The methodology of this review satisfied the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines [25]. Additionally, this review is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, registration number: CRD42020193099). Moreover, a study protocol has been published [26].

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

In June 2021, a systematic literature search was conducted in three databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, and CINAHL). The search query for PubMed is described in Table 1. A two-step process was used involving: 1. title/abstract screening and 2. full-text screening (independently by two reviewers (AH and BK). Additionally, a hand search was performed. Discussions were used when disagreements occurred. This approach was also used for data extraction and assessment of study quality.

Table 1.

Search strategy (Medline search algorithm).

Inclusion criteria were:

- cross-sectional and longitudinal observational studies analyzing the association between informal caregiving for adults (i.e., ≥18 years) and loneliness or social isolation

- operationalization of main variables with established tools

- studies in English or German language

- published in a peer-reviewed, scientific journal

In contrast, exclusion criteria were:

- studies examining grandchild care (e.g., [27,28])

- studies examining private care for chronically ill children

- studies exclusively using samples with a specific disorder among the caregivers (e.g., studies solely including caregivers with specific disorders)

- Prior to the final eligibility criteria, a pre-test was conducted (with a sample of 100 title/abstracts). Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that our criteria remained unchanged.

2.2. Data Extraction and Analysis

One reviewer (BK) carried out the data extraction, cross-checked by a second reviewer (AH). The data extraction covered the design of the study, operationalization of key variables (informal caregiving and loneliness/social isolation), characteristics of the sample, analytical approach, and important results.

2.3. Assessment of Study Quality/Risk of Bias

The study quality was assessed using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [29]. It is a well-known and widely used tool when dealing with observational studies (e.g., [30,31]).

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

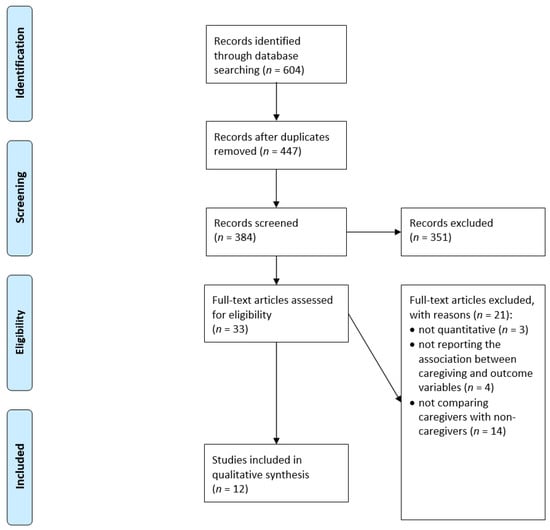

Figure 1 displays the selection process. In sum, n = 12 studies were included in our review [11,14,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. The main findings are displayed in Table 2 (if given, adjusted results are shown in Table 2). Data came from North America (n = 5, all studies from the United States), and Europe (n = 7 studies, with three studies from Germany, one study from Norway, one study from Sweden, one study from the United Kingdom, and one study using data from Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Spain, and Switzerland). While seven studies were cross-sectional [32,33,34,35,37,40,41], five studies had a longitudinal design [11,14,36,38,39]. Among the longitudinal studies, the number of waves used ranged from two to four waves. The period of observation ranged from three to twelve years.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart.

Table 2.

Study overview and important findings.

Two studies only used versions of the De Jong Gierveld scale to quantify loneliness and two studies only used different versions of the UCLA loneliness scale to quantify loneliness. Moreover, one study used the Bude and Lantermann scale to quantify perceived social isolation and the De Jong Gierveld scale to quantify loneliness. The other studies used different tools or single item measures to quantify feelings of loneliness. Half of the studies used a dichotomous variable to quantify the presence of informal caregiving. The other studies examined spousal caregiving or distinguished between, for example, current caregiving, former caregiving and non-caregiving.

Among the longitudinal studies, two studies used specific panel regression models to exploit the longitudinal data structure and to reduce the challenge of unobserved heterogeneity [42]. Based on these panel regression models, consistent estimates can be derived [42].

The sample size ranged from 101 to 29,458 observations (in sum, 91,857 observations). The studies mainly examined middle-aged and older individuals (average age ranged from 45.0 years to 83.7 years across the studies). The proportion of women in the samples mainly ranged from about 50% to 60%, whereas two studies had about 70% of women. Further details are shown in Table 2.

In the next sections, the results are displayed as follows: 1. Informal caregiving and loneliness (cross-sectional studies, thereafter longitudinal studies), and 2. Informal caregiving and social isolation (cross-sectional studies, thereafter longitudinal studies).

3.2. Informal Caregiving and Loneliness

In sum, n = 11 studies examined the association between informal caregiving and loneliness (six cross-sectional studies and five longitudinal studies).

With regard to cross-sectional studies, four studies found an association between caregiving and increased levels of loneliness [33,35,37,41], whereas one study found no association between these factors [32]. Moreover, one study found an association between caregiving and a decreased likelihood of loneliness [34]. However, this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

With regard to longitudinal studies, three studies found an association between caregiving and increased loneliness levels [11,36,39], whereas two studies did not identify significant differences [14,38]. One of the three studies which found significant differences only found these among men, but not women [11].

3.3. Informal Caregiving and Social Isolation

In sum, n = 2 studies examined the association between informal caregiving and social isolation (one cross-sectional study and one longitudinal study). Both studies did not find an association between these factors [11,40]. It should be noted that one of these studies examined both the association between informal caregiving and loneliness as well as between informal caregiving and social isolation [11].

3.4. Quality Assessment

The assessment of the study quality of the studies included in our review is displayed in Table 3. While some important criteria were achieved by all studies (e.g., clear aim of the study or valid assessments of important variables), a few other criteria were only partly (e.g., adjustment for covariates) or hardly ever met (e.g., sufficient response rate or small loss to follow-up). Nevertheless, the overall study quality was quite high (seven studies were rated as ‘good’ and five studies were rated as ‘fair’; none of the studies were rated as ‘poor’).

Table 3.

Quality Assessment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

In summary, twelve studies were included in our review (seven cross-sectional studies and five longitudinal studies)—all included studies were either from North America or Europe. The studies mainly showed an association between providing informal care and higher loneliness levels. The overall study quality was fair to good. Such knowledge about an association between informal caregiving and loneliness is of great importance for targeting target individuals at risk of increased levels of loneliness, which in turn may assist in maintaining health.

4.2. Possible Mechanisms

Rather unsurprisingly, most of the studies included found an association between the provision of informal care and increased levels of loneliness. While only single studies (e.g., [43]) identified positive health consequences of informal caregiving, most of the studies showed harmful consequences of private care (e.g., on sleep [44], mental health or life satisfaction [7,8,44,45]). These harmful consequences may contribute to feelings of loneliness. More precisely, specific depressive symptoms such as anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure) may reduce motivation to perform social activities [46]. This in turn may result in feelings of loneliness. Furthermore, the reduced sleep quality caused by performing informal care may also inhibit physical and cognitive activities [44] which can ultimately contribute to reduced loneliness scores. Similarly, a reduced satisfaction with life can directly contribute to social withdrawal or feeling lonely [47].

Furthermore, the association between informal caregiving and increased loneliness may be explained by the fact that informal caregiving limits social contacts [48,49,50]. In turn, this may enhance emotions of loneliness caused by the restricted leisure time for social activities [51], caregiving burden or emotions such as guilt or resentment [48,49,50].

4.3. Comparability of Studies

Several factors limit the comparability of the studies included. For example, both loneliness and social isolation were quantified using different tools. None of the studies examined the association between informal caregiving and objective social isolation. Informal caregiving was also assessed differently between the studies. More than half of the studies included used cross-sectional data. Out of the five longitudinal studies, only two used specific panel regression models. Such models are required to produce consistent estimates [42]. With regard to cultural differences, the included studies exclusively referred to data from North America or Europe.

4.4. Gaps in Knowledge and Guidance for Future Research

Our current systematic review determined various gaps in our current knowledge. First, more longitudinal studies are needed to identify the impact of caregiving on loneliness and social isolation. Second, more studies using data from nationally representative samples are desirable. Third, caregiving types could be taken into consideration in future studies (e.g., from pure supervision to performing nursing care services [43,52]). Fourth, the relationship between caregiver and care-recipient (e.g., spousal caregiving vs. parental caregiving or inside household caregiving vs. outside household caregiving) should be taken into consideration. Fifth, the care-recipients should be clearly characterized (e.g., care recipient with cancer vs. care recipient with dementia)—if data are available. Sixth, future research should ideally use established instruments such as the De Jong Gierveld scale or the UCLA loneliness scale. Seventh, many more studies should also consider the impact of caregiving on (perceived and objective) social isolation. Eighth, research from other areas of the world (other than Europe and North America) is urgently needed. Ninth, the underlying mechanisms in the association between caregiving and loneliness as well as social isolation should be explored. Tenth, the association between caregiving and loneliness/social isolation should be further explored during (or after) the COVID-19 pandemic. Eleventh, subgroup analyses (e.g., stratified by gender) are desirable.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

This is the first systematic review regarding the association between informal caregiving and loneliness/social isolation. The important steps were conducted by two reviewers. A meta-analysis was not performed due to study heterogeneity. Since we restricted our search to articles published in peer-reviewed articles, some important studies may be excluded from this review. However, it should be noted that a certain quality of the studies is ensured by this inclusion criterion.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our systematic review mainly identified associations between providing informal care and higher loneliness levels. This is of great importance in assisting informal caregivers in avoiding loneliness, since it is associated with subsequent morbidity and mortality. Moreover, high loneliness levels of informal caregivers may have adverse consequences for informal care recipients (e.g., in terms of earlier admission to nursing homes or decreased informal care quality). Thus, avoiding higher loneliness levels of individuals providing informal care may, more generally, assist in improving the relationship between informal caregivers and informal care recipients—which could be examined in future studies. This may also contribute to successful ageing in both informal caregivers and care recipients.

Author Contributions

The study concept was developed by A.H., B.K. and H.-H.K. The manuscript was drafted by A.H. and critically revised by B.K. and H.-H.K. The search strategy was developed by A.H. and H.-H.K. Study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment were performed by A.H. and B.K., with H.-H.K. as a third party in case of disagreements. A.H., B.K. and H.-H.K. contributed to the interpretation of the extracted data and writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit

sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Prieto-Flores, M.-E.; Forjaz, M.J.; Fernandez-Mayoralas, G.; Rojo-Perez, F.; Martinez-Martin, P. Factors associated with loneliness of noninstitutionalized and institutionalized older adults. J. Aging Health 2011, 23, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, C.R. Loneliness in care homes: A neglected area of research? Aging Health 2012, 8, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Lehnert, T.; Wegener, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Koenig, H.-H. Long-Term Care Preferences Among Individuals of Advanced Age in Germany: Results of a Population-Based Study. Gesundheitswesen (Bundesverb. Arzte Offentlichen Gesundh.) 2018, 80, 685–692. [Google Scholar]

- Hajek, A.; Lehnert, T.; Wegener, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; König, H.-H. Factors associated with preferences for long-term care settings in old age: Evidence from a population-based survey in Germany. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwar, L.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. Do informal caregivers expect to die earlier? A longitudinal study with a population-based sample on subjective life expectancy of informal caregivers. Gerontology 2021, 67, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.M.; Sousa-Poza, A. Impacts of informal caregiving on caregiver employment, health, and family. J. Popul. Ageing 2015, 8, 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. Informal caregiving and subjective well-being: Evidence of a population-based longitudinal study of older adults in Germany. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaschowitz, J.; Brandt, M. Health effects of informal caregiving across Europe: A longitudinal approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 173, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Mullan, J.T.; Semple, S.J.; Skaff, M.M. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990, 30, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallicchio, L.; Siddiqi, N.; Langenberg, P.; Baumgarten, M. Gender differences in burden and depression among informal caregivers of demented elders in the community. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2002, 17, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwar, L.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. Psychosocial consequences of transitioning into informal caregiving in male and female caregivers: Findings from a population-based panel study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 264, 113281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodaty, H.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. Psychosocial effects on carers of living with persons with dementia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1990, 24, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curvers, N.; Pavlova, M.; Hajema, K.; Groot, W.; Angeli, F. Social participation among older adults (55+): Results of a survey in the region of South Limburg in the Netherlands. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, e85–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. Impact of informal caregiving on loneliness and satisfaction with leisure-time activities. Findings of a population-based longitudinal study in germany. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 1539–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, P.; Uden, G.; Willman, A. Support for family carers who care for an elderly person at home–a systematic literature review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2004, 18, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüz, B.; Czerniawski, A.; Davie, N.; Miller, L.; Quinn, M.G.; King, C.; Carr, A.; Elliott, K.E.J.; Robinson, A.; Scott, J.L. Leisure Time Activities and Mental Health in Informal Dementia Caregivers. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2015, 7, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. Do loneliness and perceived social isolation reduce expected longevity and increase the frequency of dealing with death and dying? longitudinal findings based on a nationally representative sample. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1720–1725.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.H. Do lonely and socially isolated individuals think they die earlier? The link between loneliness, social isolation and expectations of longevity based on a nationally representative sample. Psychogeriatrics 2021, 21, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Uribe, L.A.; Caballero, F.F.; Martín-María, N.; Cabello, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Miret, M. Association of loneliness with all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, N.K.; Kanaan, M.; Gilbody, S.; Ronzi, S.; Hanratty, B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart 2016, 102, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, C.; Scambler, S.; Bond, J.; Bowling, A. Being alone in later life: Loneliness, social isolation and living alone. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2000, 10, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, N.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. The link between falls, social isolation and loneliness: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 88, 104020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenger, G.C.; Davies, R.; Shahtahmasebi, S.; Scott, A. Social isolation and loneliness in old age: Review and model refinement. Ageing Soc. 1996, 16, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunt, S.; Steverink, N.; Olthof, J.; van der Schans, C.; Hobbelen, J. Social frailty in older adults: A scoping review. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; Kretzler, B.; König, H.-H. Informal caregiving for adults, loneliness and social isolation: A study protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirke, E.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. Association between caring for grandchildren and feelings of loneliness, social isolation and social network size: A cross-sectional study of community dwelling adults in Germany. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirke, E.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. What are the social consequences of beginning or ceasing to care for grandchildren? Evidence from an asymmetric fixed effects analysis of community dwelling adults in Germany. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Hajek, A.; Kretzler, B.; König, H.-H. Multimorbidity, loneliness, and social isolation. A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Biscardi, M.; Astell, A.; Nalder, E.; Cameron, J.I.; Mihailidis, A.; Colantonio, A. Sex and gender differences in caregiving burden experienced by family caregivers of persons with dementia: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, S.R.; Schulz, R.; Donovan, H.; Rosland, A.-M. Family Caregiving During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeson, R.A. Loneliness and depression in spousal caregivers of those with Alzheimer’s disease versus non-caregiving spouses. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2003, 17, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, M.; Garten, C.; Grates, M.; Kaschowitz, J.; Quashie, N.; Schmitz, A. Veränderungen von Wohlbefinden und privater Unterstützung für Ältere: Ein Blick auf die Auswirkungen der COVID-19-Pandemie im Frühsommer 2020. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 54, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekwall, A.K.; Sivberg, B.; Hallberg, I.R. Loneliness as a predictor of quality of life among older caregivers. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 49, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, S.; Wetherell, M.A. Risk of depression in family caregivers: Unintended consequence of COVID-19. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, T.; Slagsvold, B. Feeling the squeeze? The effects of combining work and informal caregiving on psychological well-being. Eur. J. Ageing 2015, 12, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkley, L.; Zheng, B.; Hedberg, E.; Huisingh-Scheetz, M.; Waite, L. Cognitive limitations in older adults receiving care reduces well-being among spouse caregivers. Psychol. Aging 2020, 35, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson-Whelen, S.; Tada, Y.; MacCallum, R.C.; McGuire, L.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Long-term caregiving: What happens when it ends? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2001, 110, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, J.; Fortinsky, R.; Kleppinger, A.; Shugrue, N.; Porter, M. A broader view of family caregiving: Effects of caregiving and caregiver conditions on depressive symptoms, health, work, and social isolation. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Brandt, M. Long-term care provision and the well-being of spousal caregivers: An analysis of 138 European regions. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2018, 73, e24–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zwar, L.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. The impact of different types of informal caregiving on cognitive functioning of older caregivers: Evidence from a longitudinal, population-based study in Germany. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 214, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. How does beginning or ceasing of informal caregiving of individuals in poor health influence sleep quality? Findings from a nationally representative longitudinal study. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. The relation between personality, informal caregiving, life satisfaction and health-related quality of life: Evidence of a longitudinal study. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Brettschneider, C.; Eisele, M.; Lühmann, D.; Mamone, S.; Wiese, B.; Weyerer, S.; Werle, J.; Fuchs, A.; Pentzek, M.; et al. Disentangling the complex relation of disability and depressive symptoms in old age–findings of a multicenter prospective cohort study in Germany. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.M.S.; Yorgason, J.B.; Nelson, L.J.; Miller, R.B. Social withdrawal and psychological well-being in later life: Does marital status matter? Aging Ment. Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokach, A.; Miller, Y.; Schick, S.; Bercovitch, M. Coping with loneliness: Caregivers of cancer patients. Clin. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 2, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rokach, A.; Rosenstreich, E.; Brill, S.; Aryeh, I.G. Caregivers of chronic pain patients: Their loneliness and burden. Nurs. Palliat. Care 2016, 1, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, A.; Rosenstreich, E.; Brill, S.; Aryeh, I.G. People with chronic pain and caregivers: Experiencing loneliness and coping with it. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ory, M.G.; Hoffman, R.R., III; Yee, J.L.; Tennstedt, S.; Schulz, R. Prevalence and impact of caregiving: A detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. Gerontologist 1999, 39, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwar, L.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. Consequences of different types of informal caregiving for mental, self-rated, and physical health: Longitudinal findings from the German Ageing Survey. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 2667–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).