Fibromyalgia: Evidence for Deficits in Positive Psychology Resources. A Case-Control Study from the Al-Ándalus Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

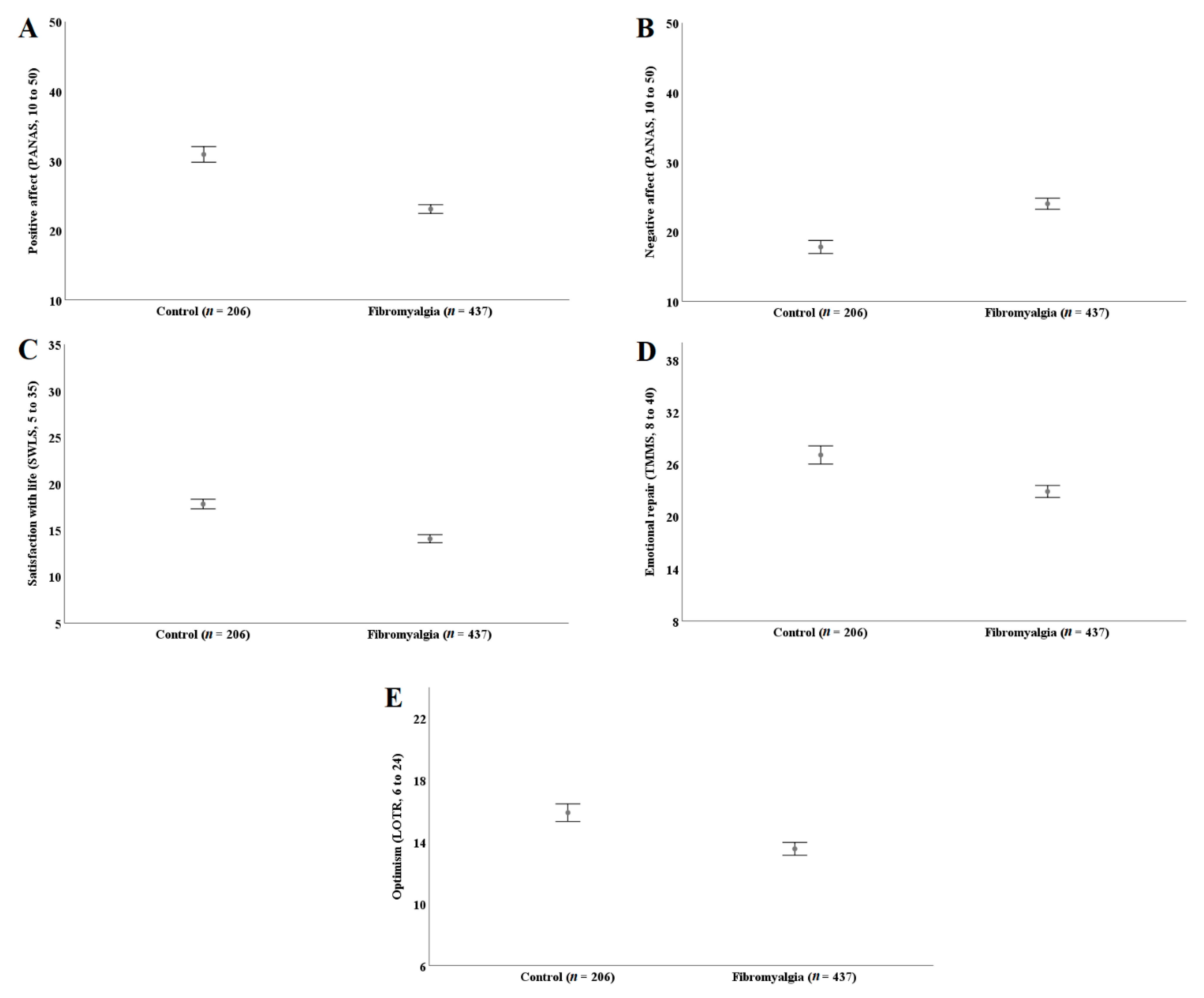

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ablin, J.N.; Wolfe, F. A Comparative Evaluation of the 2011 and 2016 Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 44, 1271–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, F.; Smythe, H.A.; Yunus, M.B.; Bennett, R.M.; Bombardier, C.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Tugwell, P.; Campbell, S.P.; Abeles, M.; Clark, P.; et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthrit. Rheum. 1990, 33, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, A.; Schaefer, C.; Ryan, K.; Baik, R.; McNett, M.; Zlateva, G. The Comparative Economic Burden of Mild, Moderate, and Severe Fibromyalgia: Results from a Retrospective Chart Review and Cross-Sectional Survey of Working-Age, U.S. Adults. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2012, 18, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.K.; Ebata, N.; Hlavacek, P.; DiBonaventura, M.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Sadosky, A. Humanistic and economic burden of fibromyalgia in Japan. J. Pain Res. 2016, 9, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Steen, T.A.; Seligman, M.E. Positive Psychology in Clinical Practice. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 629–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.; Becker, B. The Construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work. Child. Dev. 2000, 71, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castleden, M.; McKee, M.; Murray, V.; Leonardi, G. Resilience thinking in health protection. J. Public Health 2011, 33, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zautra, A.J.; Fasman, R.; Reich, J.W.; Harakas, P.; Johnson, L.M.; Olmsted, M.E.; Davis, M.C. Fibromyalgia: Evidence for Deficits in Positive Affect Regulation. Psychosom. Med. 2005, 67, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Middendorp, H.; Lumley, M.A.; Jacobs, J.W.; van Doornen, L.J.; Bijlsma, J.W.; Geenen, R. Emotions and emotional approach and avoidance strategies in fibromyalgia. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008, 64, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, A.L.; Simonelli, L.E.; Radvanski, D.C.; Buyske, S.; Savage, S.V.; Sigal, L.H. The relationship between affect balance style and clinical outcomes in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Lucas, R.E. Personality, Culture, and Subjective Well-Being: Emotional and Cognitive Evaluations of Life. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, J.A.; Zautra, A.J. Resilience: A New Paradigm for Adaptation to Chronic Pain. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2010, 14, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, A.M.; Reneman, M.F.; Stewart, R.E.; Post, M.W.; Preuper, H.R.S. Life satisfaction in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and its predictors. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 22, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reikerås, O.; Storheim, K.; Holm, I.; Friis, A.; Brox, J.I. Disability, pain, psychological factors and physical performance in healthy controls, patients with sub-acute and chronic low back pain: A case-control study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2005, 37, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conversano, C.; Rotondo, A.; Lensi, E.; Della Vista, O.; Arpone, F.; Reda, M.A. Optimism and Its Impact on Mental and Physical Well-Being. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2010, 6, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, M.D.; Anderson, E.A. The glass is not half empty: Optimism, pessimism, and health among older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.H. The role of optimism, self-esteem, and self-efficacy in moderating the relation between health comparisons and subjective well-being: Results of a nationally representative longitudinal study among older adults. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affleck, G.; Tennen, H.; Zautra, A.; Urrows, S.; Abeles, M.; Karoly, P. Women’s pursuit of personal goals in daily life with fibromyalgia: A value-expectancy analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 69, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linder, J.; Jansen, G.B.; Ekholm, J.; Ekholm, K.S. Differences in symptoms, functioning, and quality of life between women on long-term sick-leave with musculoskeletal pain with and without concomitant depression. J. Multidiscip. Health 2011, 4, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Aranda, D.; Salguero, J.M.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Emotional Regulation and Acute Pain Perception in Women. J. Pain 2010, 11, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, A.; Ramírez-Maestre, V.; Herrero, C. Emotional intelligence, personality and coping with chronic pain. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2007, 24, 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.-A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Katz, R.S.; Mease, P.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, J.L.; Winefield, J.B.; Yunus, M.B. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Jiménez, V.; Aparicio, V.A.; Alvarez-Gallardo, I.C.; Soriano-Maldonado, A.; Estevez-Lopez, F.; Delgado-Fernandez, M.; Carbonell-Baeza, A. Validation of the modified 2010 American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia in a Spanish population. Rheumatology 2014, 53, 1803–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, A.; Ezquerra, J.; Burgada, F.G.; Sala, J.M.; Díaz, A.S. Cognocitive mini-test (a simple practical test to detect intellectual changes in medical patients). Actas Luso-Espanol. Neurol. Psiquiatr. Cienc. Afin. 1979, 7, 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, B.; Chorot, P.; Lostao, L.; Joiner, T.E.; Santed, M.A.; Valiente, R.M. The PANAS scales of positive and negative affect: Factor analytic validation and cross-cultural convergence. Psicothema 1999, 11, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Estévez-López, F.; Pulido-Martos, M.; Armitage, C.A.; Wearden, A.; Allvarez-Gallardo, I.C.; Arrayas-Grajera, M.J.; Girela-Rejon, M.J.; Carbonell-Beaza, A.; Aparicio, V.A.; Greenen, R.; et al. Factor structure of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) in adult women with fibromyalgia from Southern Spain: The al-Ándalus project. PeerJ 2016, 24, e1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atienza, F.L.; Pons, D.; Balaguer, I.U.; Garcia-Merita, M. Psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale in adolescents. Psicothema 2000, 12, 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, J.M.; Luengo, A.; Romero, E.; Gómez, J.A.; Castro, C. Psicología de la Personalidad. Manual de Prácticas; Ariel Practicum: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Chico, E.; Tous, J.M. Propiedades psicométricas del test de optimismo Life Orientation Test. Psicothema 2002, 14, 673–680. [Google Scholar]

- Landero Hernández, T.; González Ramírez, R. Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española del test de optimismo revisado (LOT-R) en una muestra de personas con fibromialgia. Anised. Est. 2009, 15, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N.; Ramos, N. Validity and Reliability of the Spanish Modified Version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 94, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D.; Goldman, S.L.; Turvey, C.; Palfai, T.P. Emotional Attention, Clarity, and Repair: Exploring Emotional Intelligence Using the Trait. Meta-Mood Scale; Pennebaker, J.W., Ed.; Emotion, Disclosure, & Health: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, S.; Cuthill, I.C. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: A practical guide for biologists. Biol. Rev. 2007, 82, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Vega, S.; Arias-Congrains, J. Associated factors to pain in women with fibromyalgia. Rev. Soc. Peru Med. Interna 2012, 25, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Goubert, L.; Trompetter, H. Towards a science and practice of resilience in the face of pain. Eur. J. Pain 2017, 21, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Roots and routes to resilience and its role in psychotherapy: A selective, attachment-informed review. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2017, 19, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-López, F.; Gray, C.M.; Segura-Jiménez, V.; Soriano-Maldonado, A.; Gallardo, I.C.A.; Arrayas-Grajera, M.J.; Carbonell-Baeza, A.; Aparicio, V.A.; Delgado-Fernández, M.; Pulido-Martos, M. Independent and combined association of overall physical fitness and subjective well-being with fibromyalgia severity: The al-Ándalus project. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1865–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zautra, A.J.; Johnson, L.M.; Davis, M.C. Positive Affect as a Source of Resilience for Women in Chronic Pain. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anke, A.; Damsgård, E.; Røe, C. Life satisfaction in subjects with long-term musculoskeletal pain in relation to pain intensity, pain distribution and coping. J. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 45, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamee, P.; Mendolia, S. The effect of chronic pain on life satisfaction: Evidence from Australian data. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 121, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björnsdóttir, S.V.; Jónsson, S.H.; Valdimarsdóttir, U.A. Mental health indicators and quality of life among individuals with musculoskeletal chronic pain: A nationwide study in Iceland. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2014, 43, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Maestre, C.; Esteve, R.; López, A.E. The role of optimism and pessimism in chronic pain patients adjustment. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raak, R.; Hurtig, I.; Wahren, L.K. Coping Strategies and Life Satisfaction in Subgrouped Fibromyalgia Patients. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2003, 4, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Reca, O.; Pulido-Martos, M.; Gavilán-Carrera, B.; García-Rodríguez, I.C.; McVeigh, J.G.; Aparicio, V.A.; Estévez-López, F. Emotional intelligence impairments in women with fibromyalgia: Associations with widespread pain. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 26, 1901–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zautra, A.J.; Fasman, R.; Parish, B.P.; Davis, M.C. Daily fatigue in women with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and fibromyalgia. Pain 2007, 128, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, N.L.; Lyubomirsky, S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 65, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-López, F.; Segura-Jiménez, V.; Gallardo, I.C.A.; Borges-Cosic, M.; Pulido-Martos, M.; Carbonell-Baeza, A.; Aparicio, V.A.; Geenen, R.; Delgado-Fernández, M. Adaptation profiles comprising objective and subjective measures in fibromyalgia: The al-Ándalus project. Rheumatology 2017, 56, 2015–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Doebl, S.; Macfarlane, G.; Hollick, R. No one wants to look after the fibro patient. Understanding models, and patient perspectives, of care for fibromyalgia: Reviews of current evidence. Pain 2020, 161, 1716–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, G.L.; Kronisch, C.; Dean, L.E.; Atenzi, F.; Hauser, W.; Flub, E.; Choy, E.; Kosek, E.; Amris, K.; Branco, J.; et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Fibromyalgia (n = 437) | Control (n = 206) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 51.6 (7.1) | 50.6 (7.2) | 0.081 |

| Education level, n (%) | 0.004 | ||

| Unfinished studies | 40 (9.2) | 11 (5.3) | |

| Primary studies | 210 (48.1) | 81 (39.3) | |

| Secondary studies | 126 (28.8) | 65 (31.6) | |

| Tertiary studies | 61 (14.0) | 49 (23.8) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.700 | ||

| Married | 332 (76.0) | 149 (72.3) | |

| Single | 34 (7.8) | 21 (10.2) | |

| Separated/divorced | 50 (11.4) | 26 (12.6) | |

| Widow | 21 (4.8) | 9 (4.4) | |

| Missing data | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Time since fibromyalgia diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| <1 year | 28 (6.6) | ||

| 1–5 years | 147 (34.6) | ||

| >5 years | 250 (58.8) | ||

| Missing data | 12 (2.7) | ||

| Time since first symptoms until fibromyalgia diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| <1 year | 41 (9.6) | ||

| 1–5 years | 181 (42.6) | ||

| >5 years | 203 (47.8) | ||

| Missing data | 12 (2.7) | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arrayás-Grajera, M.J.; Tornero-Quiñones, I.; Gavilán-Carrera, B.; Luque-Reca, O.; Peñacoba-Puente, C.; Sierra-Robles, Á.; Carbonell-Baeza, A.; Estévez-López, F. Fibromyalgia: Evidence for Deficits in Positive Psychology Resources. A Case-Control Study from the Al-Ándalus Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212021

Arrayás-Grajera MJ, Tornero-Quiñones I, Gavilán-Carrera B, Luque-Reca O, Peñacoba-Puente C, Sierra-Robles Á, Carbonell-Baeza A, Estévez-López F. Fibromyalgia: Evidence for Deficits in Positive Psychology Resources. A Case-Control Study from the Al-Ándalus Project. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):12021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212021

Chicago/Turabian StyleArrayás-Grajera, Manuel Javier, Inmaculada Tornero-Quiñones, Blanca Gavilán-Carrera, Octavio Luque-Reca, Cecilia Peñacoba-Puente, Ángela Sierra-Robles, Ana Carbonell-Baeza, and Fernando Estévez-López. 2021. "Fibromyalgia: Evidence for Deficits in Positive Psychology Resources. A Case-Control Study from the Al-Ándalus Project" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 12021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212021

APA StyleArrayás-Grajera, M. J., Tornero-Quiñones, I., Gavilán-Carrera, B., Luque-Reca, O., Peñacoba-Puente, C., Sierra-Robles, Á., Carbonell-Baeza, A., & Estévez-López, F. (2021). Fibromyalgia: Evidence for Deficits in Positive Psychology Resources. A Case-Control Study from the Al-Ándalus Project. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212021