Further Inspection: Integrating Housing Code Enforcement and Social Services to Improve Community Health

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Housing, Health, and the Role of the Housing Inspector

1.2. Housing and Multisector Collaboration

1.3. Placing Modern Housing Inspections in Historical Context

1.4. Objective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

- During routine inspections, inspectors identify residents in need of support beyond what inspectors can provide, ranging from crisis assistance (e.g., a family being evicted) to vital access to basic needs (e.g., heating fuel). Referrals can be made for landlords as well as tenants. No formal screening process is used in making referrals.

- To make a referral, inspectors obtain consent from residents and call a designated case manager at the social service agency, CAPIC. Inspectors received training from CAPIC’s case manager on this process.

- A case manager then contacts the resident, most often meeting them at their home, to determine what type of support is needed. If a resident accepts, the case manager connects them with services and provides follow-up care. Housing inspectors follow up to ensure housing code violations, if present, are corrected.

- CAPIC shares outcomes and progress with inspectors and the City Manager via monthly updates and quarterly reports.

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Quantitative Data

2.4. Qualitative Data

3. Results

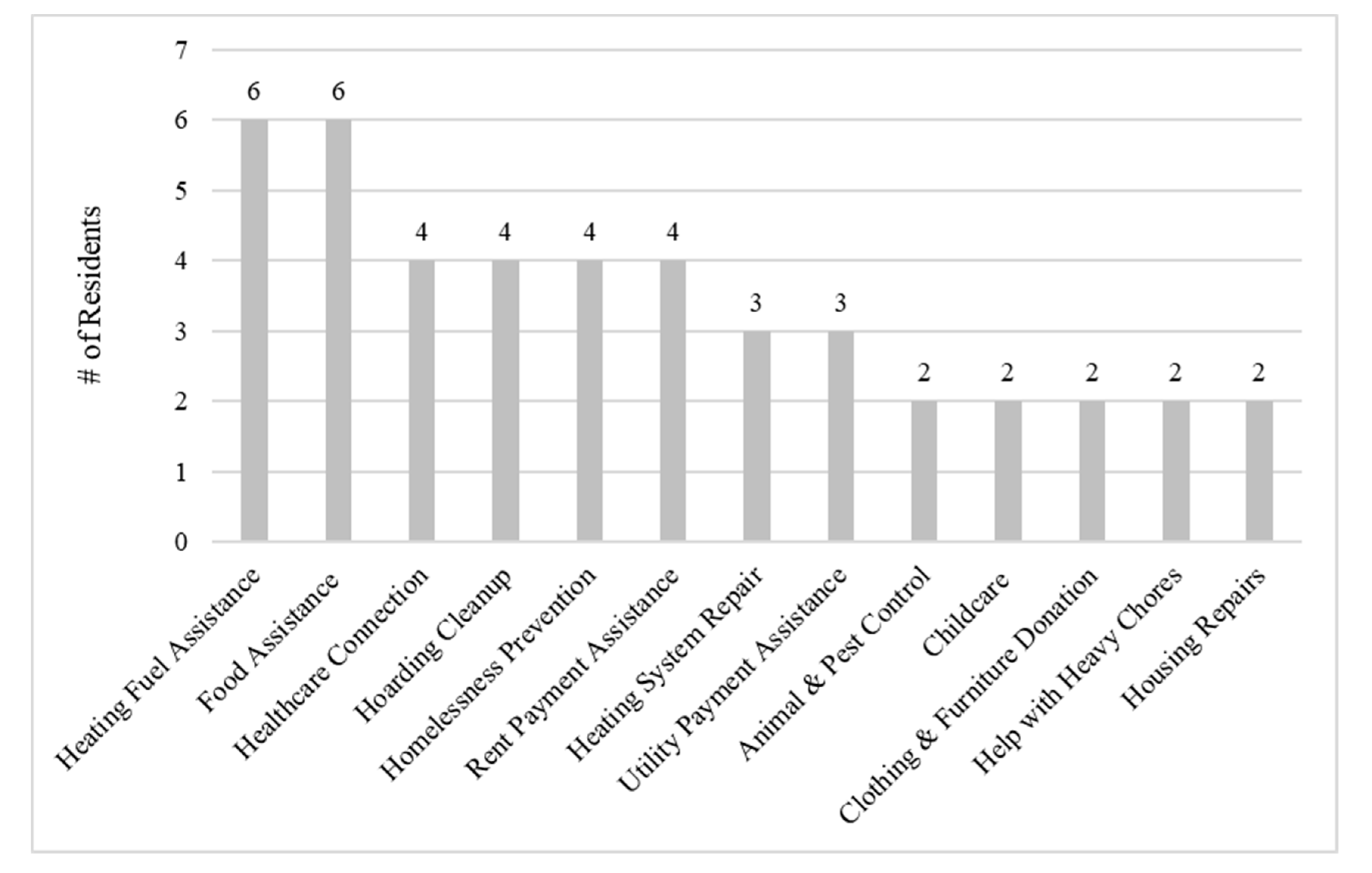

3.1. Referral Characteristics

3.2. Qualitative Interview Themes

3.2.1. Challenges Inspectors Faced before the Referral Program

“So, we see all these social service problems. And there’s really not a lot we can do. It’s terrible… When you’re alone in the house, you see how people live. You see these people living with no food or you see this person that clearly has a mental health issue and, you know, that’s not our job. There’s not a lot we [could] do.”(Inspector 2).

“It would put a huge strain on my office. It would put a huge strain on each individual neighborhood. We have these issues that go on forever… And when we’re not working on it… there is no outcome, the neighborhood suffers, the family suffers, everybody suffers.”(Inspector 3).

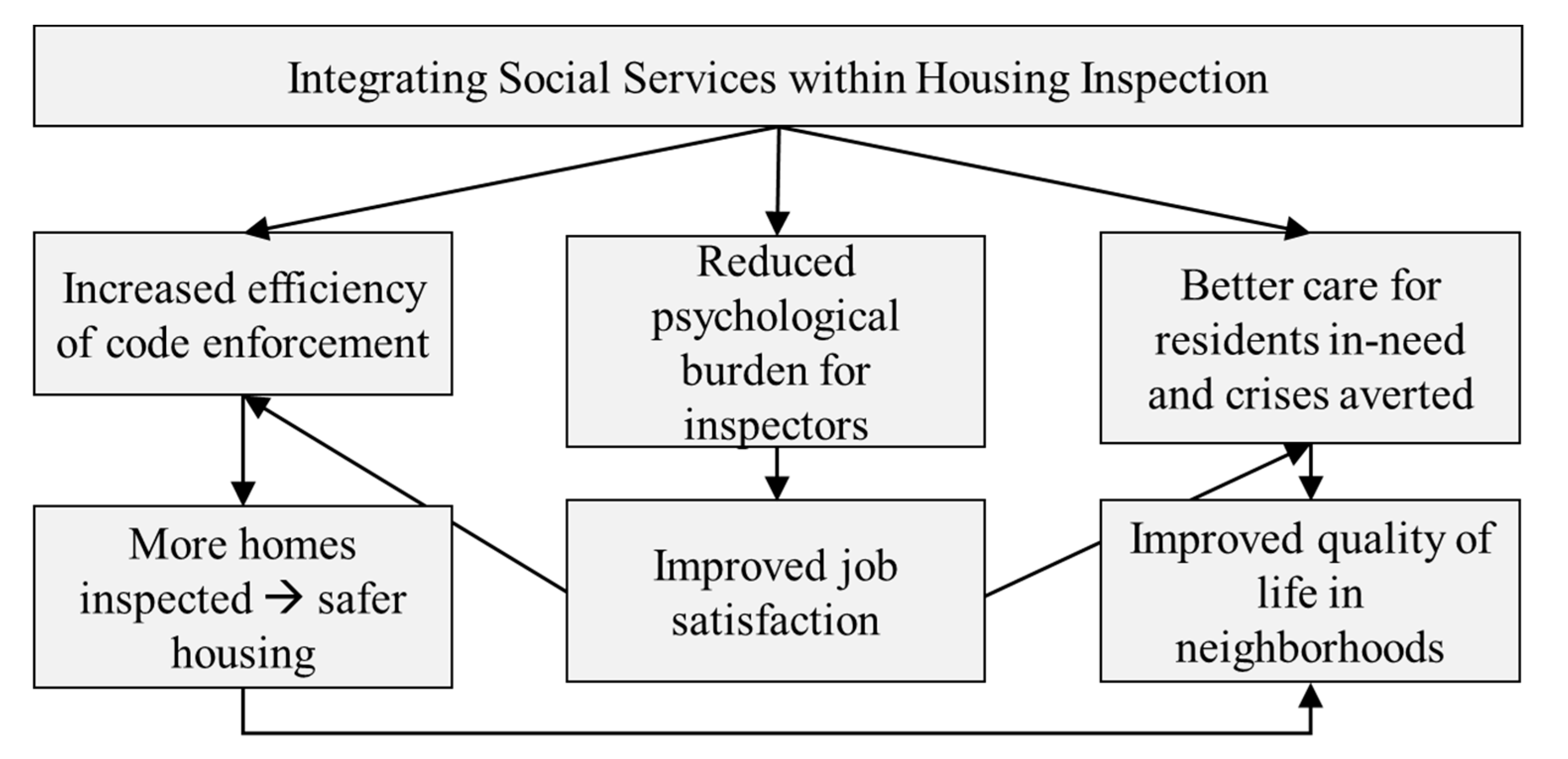

3.2.2. Impact of the Program on Inspector’s Work

“[The Social Service Referral Program] took away the piece of the inspection for certain types of people that was causing problems for us. If people are going to be evicted or have mental health issues or can’t pay rent–these we can refer to CAPIC… CAPIC has time to case manage people’s needs. We still resolve problems in-house; we just refer our most challenging that are outside the scope of violations.”(Inspector 1).

“There’s more free time … so once we do our inspection and write up our report and get CAPIC involved … you don’t have to have it in the back of your head the whole time and check in on it every day… it gives you peace of mind, it releases my inspectors to do other work… It’s a good feeling, takes a lot of stress off us.”(Inspector 3).

“What’s interesting is that now these problems that were experienced by inspectors, but didn’t necessarily come up to our level, now do… They were simply wrestling with these issues all on their own. Making phone calls, trying to find the resources to address the issues. Sometimes failing, sometimes succeeding, but in a really scattershot way. I think that was sort of an invisible workload down in [The Inspectional Services Department] that has now become part of an understood process of engagement… and given a form and a direction on how to solve these problem situations.”(City Leader 1).

“When I challenge [inspectors] on the number of cases… it’s the intractable cases that can be time eaters for inspectors and endanger the client… So, I would say it makes [inspectors] more effective and therefore engenders a sense of actually assisting people to a solution that’s helpful to [residents] rather than punitive.”(City Leader 1).

“I’m only going to refer people who really need the services–who are destitute or needs can’t be met otherwise.”(Inspector 1).

3.2.3. Impact on Social Service Provision

“I spend more time with them [residents referred by inspectors]. Sometimes a client comes in here [to CAPIC] and I’m issuing them a food gift card. I don’t really know about their background… or living situation. I don’t know what their issue is, apart from they’re coming in and they’re telling me, ‘I’m hungry.’ Through [the Social Service Referral Program], it’s a more personal connection I have with the clients.”(Case Manager).

3.2.4. Impact on Residents and the Community

“When you take the biggest problem of [residents’] lives … and it gives them a better-quality life … dealing with their medical issues, their families, and mental health issues, things like that.”(Inspector 1).

“My first thought was to call the police. And now I’m thinking let me get [CAPIC] involved.”(Inspector 2).

“If you have one bad building, everything else is so much worse. Once you fix that one building the rest of the neighborhood gets better. Kids are going out and playing on the sidewalk where they weren’t before because the guy had, you know, prostitutes and drug addicts living at his house. So, when he’s kept in check, it changes the whole neighborhood … So, in most of these [cases] we’ve referred … it’s almost like the whole neighborhood had a problem. So, it’s helping the whole neighborhood, not just one person or one person’s life.”(Inspector 3).

3.2.5. Enabling Environment

“As far as I’m concerned, it’s real successful because sometimes it just takes a phone call for me … And it’s like ‘tag, you’re it’ and [the case manager] carries the ball, and she’s really good.”(Inspector 2).

“When I raised this as a budgetary issue with [the Director of Inspectional Services] or informally with his staff about moving forward with the program, there is no hesitation on their part … and they wouldn’t simply endorse something because it was there and occasionally it may be okay. So, I trust their judgements when they say to me, ‘This is really important for us to continue’.”(City Leader 2).

“You’ve got to identify the service provider who has the … case management experience to do something like this. … who understands all the connections, that has experience with all the resources that are out there on the state and nonprofit level and is able to bring those in to solve problems. … And on the day-to-day level, certainly making it as simple as possible. [Inspectors] didn’t want to have a complicated reporting system … so shifting the tracking and documentation of case management to the service provider so that it’s not an additional burden on the inspector was important to us.”(City Leader 1).

3.2.6. Limitations and Generalizability of the Program

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rolfe, S.; Garnham, L.; Godwin, J.; Anderson, I.; Seaman, P.; Donaldson, C. Housing as a social determinant of health and wellbeing: Developing an empirically-informed realist theoretical framework. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, J.; Higgins, D.L. Housing and Health: Time Again for Public Health Action. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.R. Housing and Health Inequalities: Review and Prospects for Research. Hous. Stud. 2000, 15, 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, N.; Ault, M.; Viveiros, J. The Impacts of Affordable Housing on Health: A Research Summary. 2015. Available online: http://www.nhc.org/2015-impacts-of-aff-housing-health (accessed on 21 March 2017).

- Chan, J.H.L.; Ma, C.C. Public Health in the Context of Environment and Housing. In Primary Care Revisited: Interdisciplinary Perspectives for a New Era; Fong, B.Y.F., Law, V.T.S., Lee, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovell-Ammon, A.; Mansilla, C.; Poblacion, A.; Rateau, L.; Heeren, T.; Cook, J.T.; Zhang, T.; de Cuba, S.E.; Sandel, M.T. Housing Intervention For Medically Complex Families Associated With Improved Family Health: Pilot Randomized Trial. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beck, A.F.; Huang, B.; Chundur, R.; Kahn, R.S. Housing code violation density associated with emergency department and hospital use by children with asthma. Health Aff. Proj. Hope 2014, 33, 1993–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Acquaye, L. Low-income homeowners and the challenges of home maintenance. Community Dev. 2011, 42, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gove, W.R.; Hughes, M.; Galle, O.R. Overcrowding in the Home: An Empirical Investigation of Its Possible Pathological Consequences. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1979, 44, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, G.C.; Vernon, T.M. National Healthy Housing Standard|NCHH, National Center for Healthy Housing. 2014. Available online: https://nchh.org/tools-and-data/housing-code-tools/national-healthy-housing-standard/ (accessed on 12 April 2019).

- Ahrens, M. NFPA’s Smoke Alarms in U.S. Home Fires. 2019. Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/Data-research-and-tools/Detection-and-Signaling/Smoke-Alarms-in-US-Home-Fires (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Wang, C.; Abou El-Nour, M.M.; Bennett, G.W. Survey of pest infestation, asthma, and allergy in low-income housing. J. Community Health 2008, 33, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, N.W.; Chokshi, D.A.; Gourevitch, M.N. Improving population health in US cities. JAMA 2013, 309, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosofsky, A.; Reid, M.; Sandel, M.; Zielenbach, M.; Murphy, J.; Scammell, M.K. Breathe Easy at Home: A Qualitative Evaluation of a Pediatric Asthma Intervention. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2016, 3, 2333393616676154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ChangeLab Solutions. Code Enforcement Strategies for Healthy Housing, Oakland, California. 2015. Available online: www.changelabsolutions.org/healthy-housing (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- de Jong, J. Dealing with Dysfunction: Innovative Problem Solving in the Public Sector; Brookings Inst. Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Riis, J.A.; Sante, L. How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York; Reprint edition; Penguin Classics: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krumbiegel, E. Hygiene of Housing. AJPH 1951, 41. Available online: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.41.5_Pt_1.497 (accessed on 25 October 2018). [CrossRef]

- Björkman, J. The Right to a Nice Home: Housing inspection in 1930s Stockholm. Scand. J. Hist. 2012, 37, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivey, A. On Closer Inspection: Learning to Look at the Whole Home Environment. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, A320–A323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stacy, C.P.; Schilling, J.; Barlow, S.; Gourevitch, R.; Meixell, B.; Modert, S.; Crutchfield, C.; Sykes-Wood, E.; Urban, R. Strategic Housing Code Enforcement and Public Health. Urban Inst. 2018. Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/strategic-housing-code-enforcement-and-public-health (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Adamkiewicz, G.; Zota, A.R.; Fabian, M.P.; Chahine, T.; Julien, R.; Spengler, J.D.; Levy, J.I. Moving Environmental Justice Indoors: Understanding Structural Influences on Residential Exposure Patterns in Low-Income Communities. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101 (Suppl. 1), S238–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamkiewicz, G.; Spengler, J.D.; Harley, A.E.; Stoddard, A.; Yang, M.; Alvarez-Reeves, M.; Sorensen, G. Environmental Conditions in Low-Income Urban Housing: Clustering and Associations With Self-Reported Health. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1650–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; Saegert, S. Residential Crowding in the Context of Inner City Poverty. In Theoretical Perspectives in Environment-Behavior Research; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, K. How Cities Can Use Housing Data to Predict COVID-19 Hotspots: Lessons from Chelsea, MA. Data-Smart City Solut. 2020. Available online: https://datasmart.ash.harvard.edu/news/article/how-cities-can-use-housing-data-predict-covid-19-hotspots-lessons-chelsea-ma (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- Ahmad, K.; Erqou, S.; Shah, N.; Nazir, U.; Morrison, A.R.; Choudhary, G.; Wu, W.-C. Association of Poor Housing Conditions with COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality Across US Counties. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, C. Map Monday: Predicting Risk of Opioid Overdoses in Providence. Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation. 2018. Available online: https://datasmart.ash.harvard.edu/news/article/map-monday-predicting-risk-opioid-overdoses-providence (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- US Census. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Chelsea City, Massachusetts. 2017. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/chelseacitymassachusetts/RHI125216 (accessed on 6 June 2018).

- Ambrosino, T.G. City of Chelsea Comprehensive Housing Analysis and Strategic Plan, City of Chelsea, MA, Chelsea, MA, 2017. Available online: https://www.chelseama.gov/sites/chelseama/files/uploads/chelsea_housing_strategy_volume_1_final_final_final.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Mass.gov. PHIT Data: Chronic Disease Hospitalizations. 2017. Available online: https://www.mass.gov/guides/phit-data-chronic-disease-hospitalizations (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- RWJF. Chelsea, Massachusetts: 2017 RWJF Culture of Health Prize Winner—RWJF. 2017. Available online: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/features/culture-of-health-prize/2017-winner-chelsea-mass.html (accessed on 23 June 2020).

- City of Chelsea. The 5 Year Certificate of Habitability Rental Housing Inspection Initiative. 2014. Available online: https://www.chelseama.gov/sites/chelseama/files/uploads/5_year_coh-eng-8-2016_0.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Robb, K. Further Inspection: Leveraging Housing Inspectors and City Data to Improve Public Health in Chelsea, MA. Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/40976724 (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- de Jong, J. Innovation Field Lab. 2017. Available online: https://ash.harvard.edu/innovation-field-lab (accessed on 2 January 2019).

- Robb, K. On Further Inspection: Engaging housing inspectors to improve public health in Chelsea, Massachusetts. Medium 2020. Available online: https://medium.com/@HarvardAsh/on-further-inspection-21794f3c840f (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- CAPIC. Community Action Programs Inter-City, Inc. 2020. Available online: http://www.capicinc.org/Eng/E_About.html (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Taylor, B.; Henshall, C.; Kenyon, S.; Litchfield, I.; Greenfield, S. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond, M. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City; Broadway Books: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, H.; Conant, R.; Soriano, T.; McCormick, W. The Past, Present, and Future of House Calls. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2009, 25, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MDRC. Evidence-Based Home Visiting Models. 2012. Available online: https://www.mdrc.org/evidence-based-home-visiting-models (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Stuart, G.; de Jong, J.; Kaboolian, L. Embedding Education in Everyday Life. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2017. Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/embedding_education_in_everyday_life (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Sparrow, M.K. The Regulatory Craft; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/book/the-regulatory-craft/ (accessed on 23 December 2018).

| Demographic Characteristics | Proportion of Residents Referred to Services 1 |

|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 53% (8) |

| Age | |

| 25–39 | 13% (2) |

| 40–59 | 20% (3) |

| 60–79 | 53% (8) |

| 80+ | 7% (1) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 7% (1) |

| Black (not Hispanic/Latino) | 7% (1) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 27% (4) |

| White (Not Hispanic/Latino) | 40% (6) |

| Unknown | 20% (3) |

| Physically disabled | 53% (8) |

| Has children under 5 years | 20% (3) |

| Senior (aged 60+) | 60% (9) |

| Referral Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Referral offer | |

| Accepted on first offer | 60% (9) |

| Accepted after two or more offers | 27% (4) |

| Declined | 7% (1) |

| Unknown | 7% (1) |

| Connection to social services | |

| First connection to services | 20% (3) |

| Previously connected to services | 33% (5) |

| Currently receives other services | 47% (7) |

| Number of contacts made between resident and case manager | mean: 9, range: 1–33 |

| Number of service types received | mean: 3, range: 1–5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Robb, K.; Marcoux, A.; de Jong, J. Further Inspection: Integrating Housing Code Enforcement and Social Services to Improve Community Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12014. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212014

Robb K, Marcoux A, de Jong J. Further Inspection: Integrating Housing Code Enforcement and Social Services to Improve Community Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):12014. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212014

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobb, Katharine, Ashley Marcoux, and Jorrit de Jong. 2021. "Further Inspection: Integrating Housing Code Enforcement and Social Services to Improve Community Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 12014. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212014

APA StyleRobb, K., Marcoux, A., & de Jong, J. (2021). Further Inspection: Integrating Housing Code Enforcement and Social Services to Improve Community Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12014. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212014