Considering Autonomous Exploration in Healthy Environments: Reflections from an Urban Wildscape

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

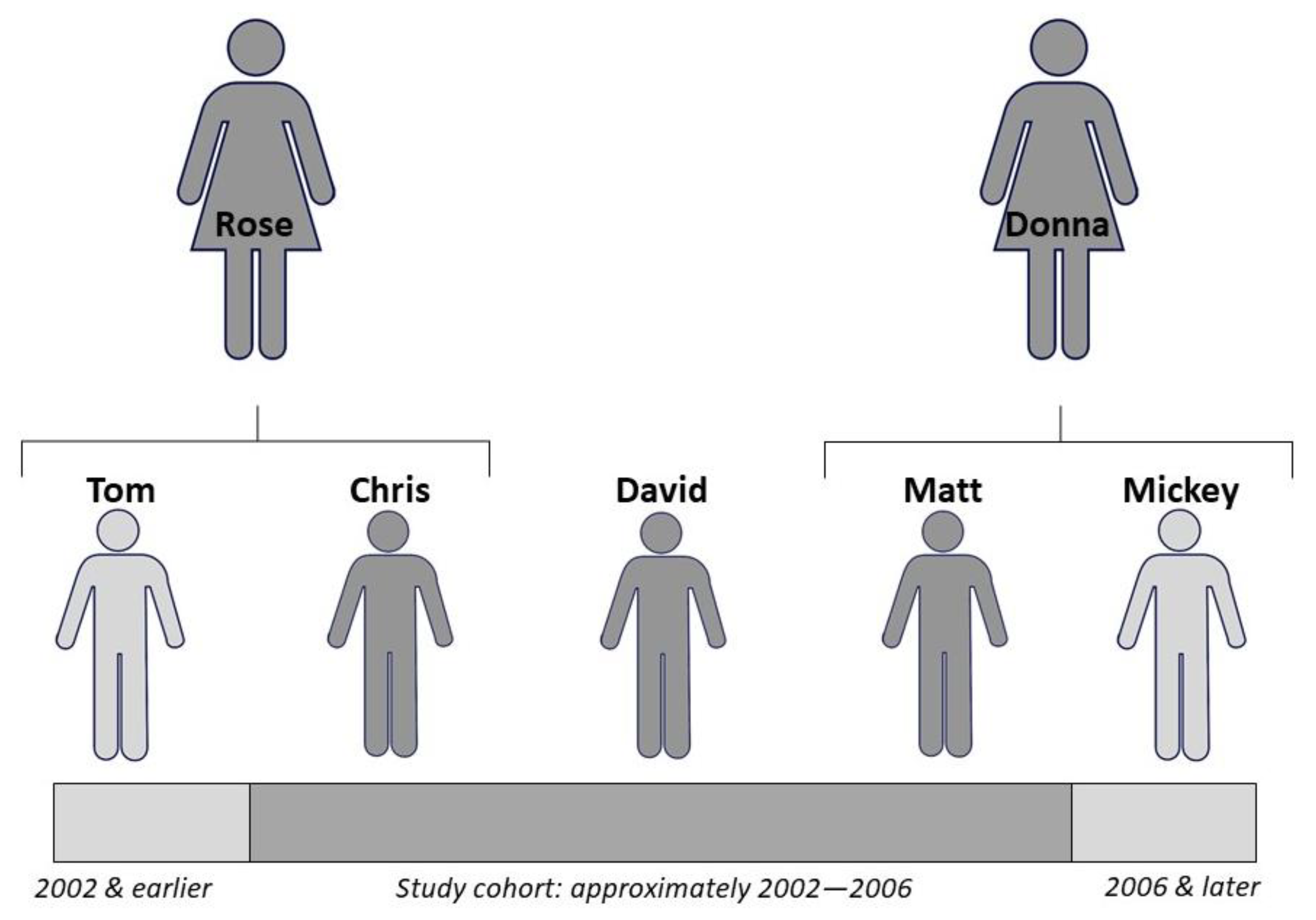

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Thick Description

3. Results

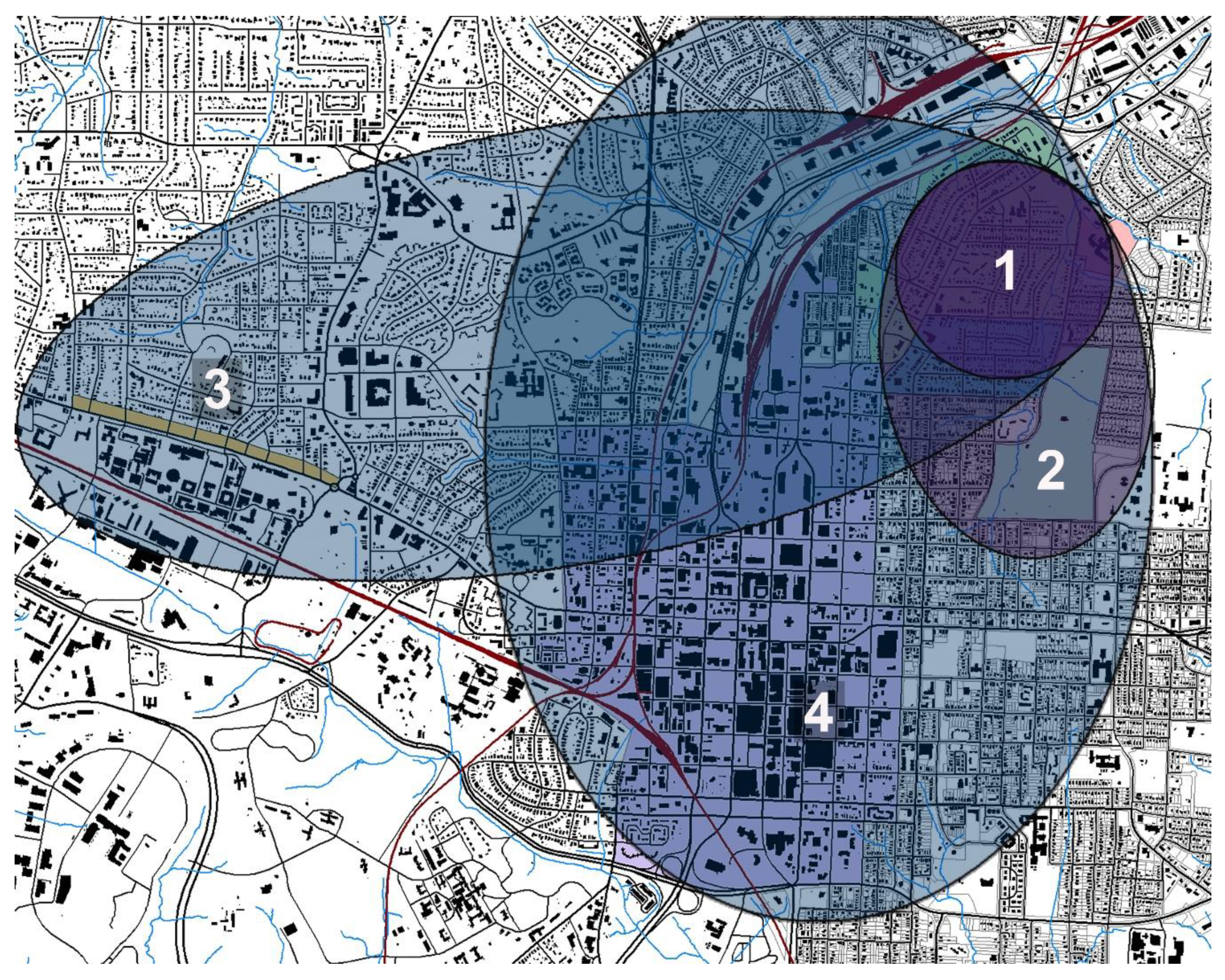

3.1. When and Where: Context

I think it is more of an attitude of not worrying and making sure that our kids have exposure to as much as we can expose them to, you know, not trying to sequester them too much in a controlled and exclusive environment, which is one reason they have always gone to public school and one reason we lived downtown. The last thing in the world we would want is them and us to be imprisoned in some sort of gated community. We are very much against that. I mean, we don’t like it. We want to meet different people.

“I had some concern about the creek being not clean, the water, but I wanted there to be more creeks and more options since this was really the only one around. I was looking for places like the creek, and we didn’t have enough of them. The free places for kids to play, and there was very little public land, very little non-private land for the kids to play in here, and they were always being chased off, property, so I thought it was a real gift to have the creek for them to play in. They had so much fun and created these lifelong bonds that any kind of risk, health risk, I am hoping is not that great.”

“It’s funny I’m not a germaphobe and never have been. In fact, I do feel like it’s important to be exposed to more [germs] because if you’re not you’re gonna get more sick. And we’re lucky, I mean, at least as far as I knew. I hadn’t seen any major concerns. They knew not to drink it. You’ve got to be careful about that and you know if you’ve got cuts and stuff…just making sure that they were cleaned really well when they came back, but overall, I’ve always felt like it’s good.”

I think a lot of it was wanting to be unsupervised and have the freedom to like do whatever you want really and kind of go wild, because after being in school all day and having teachers telling you: you can’t go behind the trees, you can’t go in like certain corners of the playground. You just really are ready to learn for yourself and have some freedom and not have someone tell you what to do all the time.

And I feel like the reason why we were hanging out with each other was because we had parents that were, you know ‘ok yeah you guys can do that’ …and the parents that were like ‘uh we want you to stay inside the house’ or you know ‘stay within this block’ then we weren’t really hanging out with them because we were outside the block.

The creek was our place to explore. It was our little realm where we could go and see everything there was to see and as we got older and we all got bikes and our parents let us roam around

Raleigh as opposed to just the creek. Raleigh—I would say became our creek in a way because it was just our place to explore.

3.2. Who: The Social Action and Cultural Context

“There were some parents who were trying to tell the kids to put the sticks down and “Let’s play nice” and “You can’t do that,” and it was just way too much parental interference [at the creek]. There sometimes will be accidents, but my experience has been there has never been any great harm done to anyone. I would much rather my kids grow up… having a full experience of life and having some adventure than, just being chauffeured around in air-conditioned minivans to their next lesson or sports event. To me, that is not a childhood.”

“There was a neighbor. She had an only child, very protective of him. I guess the school was having a fair, and I offered to watch her child and another neighbor’s child. They’re both very protective, and they wouldn’t let me. They would not leave their kids with me because I was too cavalier, and I was not protective enough of children. So, yeah, there is some backlash with parents who, in my mind, are hung up and worried too much, and that is their issue.”

“A lot of times it was kind of like trying to show [high school friends] our lifestyle to get them to understand and like it is funny like bringing people to the creek and showing them around Raleigh and like ‘That is what we used to do.’”

The creek was our place to explore, and it was like our little realm where we could go and see everything there was to see and as we got older, and we all got bikes and our parents let us roam around Raleigh as opposed to just the creek. Raleigh—I would say became our creek in a way because it just was our place to explore.

We climbed a lot of the cranes downtown. Then we climbed a lot of the buildings. There’s one warehouse that was where the new Citric’s building is. You can get on top of it pretty easily. It had a really nice view, and so we hung out there like a whole lot of nights or like a lot of mornings I guess we’d go there and watch the sunrise.

Chris confirms, “Those friendships were like almost separate in the world or like in my other friendships they were kind of different. It was just a very different thing, and I don’t think I have ever made other friendships like that.”I think about my friends, like my neighborhood friends, that I grew up with. We will just like never go away. Like it’s not an option. They are close as family to me. Whether we get into a fight, and someone stomps out of the room, it is not even a question like they are going to come back 20 min and it is going to be the same.

Rose confirms,I definitely think of them differently just because of the different things that we have been through together and like the different obstacles we have been through together. Just like really great and shitty times together that we experienced in downtown but yea it has been phenomenal.

All of the sudden here’s just this perfect environment for them to develop as friends, develop as individuals, to learn so much, to learn how to interact with each other, to learn how to have fights, to learn how to solve you know to resolve those issues. I think it would have been very different [without the creek]. I mean I still think they probably would have been friends, but I think their paths may have gone different ways. It’s an amazing impact that this one place had on them.

3.3. What and Why: Behavior and Intentionality

We have always been adventurous, going places and visiting other cultures. My husband and I met in the Peace Corps in Africa, and in fact, we are headed back to Africa next week with the whole family. And I think being open to diversity and other cultures and other people has always been something we have supported and been interested in.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frumkin, H.; Wendel, A.; Abrams, R.F.; Malizia, E. An Introduction to Healthy Places. In Making Healthy Places: Designing and Building for Health, Well-Being, and Sustainability; Dannenburg, A., Frumkin, H., Jackson, R., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aunola, K.; Stattin, H.; Nurmi, J.-E. Parenting styles and adolescents’ achievement strategies. J. Adolesc. 2000, 23, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.E.; Lumeng, J.C.; Appugliese, D.P.; Kaciroti, N.; Bradley, R.H. Parenting styles and overweight status in first grade. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 2047–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rees, G.; Goswami, H.; Pople, L.; Bradshaw, J.; Keung, A.; Main, G. The Good Childhood Report 2013; The Children’s Society: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, E.A.; Chandler, M.; Heffer, R.W. The influence of parenting styles, achievement motivation, and self-efficacy on academic performance in college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2009, 50, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K. The Development of Place Identity in the Child. In Spaces for Children: The Built Environment and Child Development; Weinstein, C.S., David, T.G., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Alparone, F.R.; Pacilli, M.G. On children’s independent mobility: The interplay of demographic, environmental, and psychosocial factors. Child. Geogr. 2012, 10, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsen, K.; Gilliland, J.; Hess, P.; Tucker, P.; Irwin, J.; He, M. The Influence of the Physical Environment and Sociodemographic Characteristics on Children’s Mode of Travel to and From School. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prezza, M. Children’s independent mobility: A review of recent Italian literature. Child. Youth Environ. 2007, 17, 293–318. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, P. The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents. Am. J. Play 2011, 3, 443–463. [Google Scholar]

- Pooley, C.G.; Turnbull, J.; Adams, M. The journey to school in Britain since the 1940s: Continuity and change. Area 2005, 37, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, K.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bulsara, M.; Trapp, G.; Timperio, A.; McCormack, G.; Van Niel, K. Does the walkability of neighbourhoods affect children’s independent mobility, independent of parental, socio-cultural and individual factors? Child. Geogr. 2014, 12, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R. Children’s Experience of Place; Irvington: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, H.E.; Griffin, E. Decreasing experiences of home range, outdoor spaces, activities and companions: Changes across three generations in Sheffield in north England. Child. Geogr. 2015, 13, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rubin, K.H. The Play Observation Scale (POS); Center for Children, Relationships, and Culture, University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Skår, M.; Krogh, E. Changes in children’s nature-based experiences near home: From spontaneous play to adult-controlled, planned and organised activities. Child. Geogr. 2009, 7, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, H.; Whitaker, R. Resurrecting Free Play in Young Children: Looking beyond fitness and fatness to attention, affiliation, and affect. Arch. Pediatrics Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Juster, F.T.; Ono, H.; Stafford, F. Changing Times of American Youth: 1981-2003. In Child Development Supplement; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rideout, V.; Foehr, U.; Roberts, D. Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8- to 18- Year-Olds; The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lythcott-Haims, J. How to Raise an Adult: Break Free of the Overparenting Trap and Prepare Your Kid for Success; Henry Holt & Co, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau, A. Invisible Inequality: Social Class and Childrearing in Black Families and White Families. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2002, 67, 747–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, C.G.; Turnbull, J.; Adams, M. A Mobile Century? Changes in Everyday Mobility in Britain in the Twenthieth Century; Ashgate Publishing Co.: Burlington, VT, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pain, R. Paranoid parenting? Rematerializing risk and fear for children. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2006, 7, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OJJDP. OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book: Child Victims of Sexual Assault by Relationship and Offender Age; Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- OJJDP. OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book: Victim-Offender Relationship in Juvenile Homicides by Age of Victim, 1980–2015; Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Prezza, M.; Alparone, F.R.; Cristallo, C.; Luigi, S. Parental perception of social risk and of positive potentiality of outdoor autonomy for children: The development of two instruments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüttenmoser, M. Children and their living surroundings: Empirical investigations into the significance of living surroundings for the everyday life and development of children. Child. Environ. 1995, 12, 403–413. [Google Scholar]

- Karsten, L. Mapping childhood in Amsterdam: The spatial and social construction of children’s domains in the city. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2002, 93, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Salmon, J.; Ball, K. Individual, social and physical environmental correlates of children’s active free-play: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skenazy, L. Free-Range Kids: Giving Our Children the Freedom We Had without Going Nuts with Worry; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Graue, M.E.; DiPerna, J. Redshirting and early retention: Who gets the” gift of time” and what are its outcomes? Am. Educ. Res. J. 2000, 37, 509–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A. Beyond the Pros and Cons of Redshirting. The Atlantic, 2015; Retrieved 15 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kniffin, K.M.; Hanks, A.S. Revisiting Gladwell’s Hockey Players: Influence of Relative Age Effects upon Earning the PHD. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2016, 34, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bassok, D.; Reardon, S.F. “Academic redshirting” in kindergarten: Prevalence, patterns, and implications. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2013, 35, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bodovski, K.; Farkas, G. “Concerted cultivation” and unequal achievement in elementary school. Soc. Sci. Res. 2008, 37, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedersdorf, C. Working Mom Arrested for Letting Her 9-Year-Old Play Alone at Park. The Atlantic, 15 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C. Florida Mom Arrested after Letting 7-Year-Old Walk to the Park Alone. CNN, 1 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McCarren, A. Parents in Trouble Again for Letting Kids Walk Alone. USA Today, 13 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ekins, E. UPDATED/Poll: 68 Percent of Americans Don’t Think 9-Year-Olds Should Play at the Park Unsupervised. Reason-Rupe Poll, 19 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, M. Utah’s ‘Free-Range Parenting’ Law Said to Be First in the Nation. The Washington Post, 28 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P. Towards a developmental theory of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derr, V. Children’s Sense of Place in Northern New Mexico. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; Kyttä, M.; Hartig, T. Restorative experience, self-regulation, and children’s place preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Little, S.; Derr, V. The Influence of Nature on a Child’s Development: Connecting the Outcomes of Human Attachment and Place Attachment. In Research Handbook on Childhoodnature: Assemblages of Childhood and Nature Research; Cutter-Mackenzie, A., Malone, K., Hacking, E.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2020; pp. 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- grebo58. Boys of the Creek. 2012. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bDjYj7oafe4 (accessed on 23 August 2014).

- Brussoni, M.; Gibbons, R.; Gray, C.; Ishikawa, T.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Bienenstock, A.; Chabot, G.; Fuselli, P.; Herrington, S.; Janssen, I. What is the relationship between risky outdoor play and health in children? A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6423–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, P. Risky Play: What children love and need it. In The Routledge Handbook of Designing Public Spaces for Young People: Processes, Practices, and Policies for Youth Inclusion; Loebach, J.E., Little, S., Cox, A., Owens, P.E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Evaluation through Observation. In Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 121–193. [Google Scholar]

- Little, S.; Rice, A. At the Intersection of the Social and Physical Environments: Building a Model of the Influence of Caregivers and Peers on Direct Engagement with Nature. Geographies 2021, 1, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponterotto, J.G.; Grieger, I. Effectively communicating qualitative research. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 35, 404–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Grounded Theory Methodology: An overview. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publications, Incorporated: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Groat, L.; Wang, D. Architectural Research Methods; Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ponterotto, J.G. Brief note on the origins, evolution, and meaning of the qualitative research concept thick description. Qual. Rep. 2006, 11, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. Thick Description. In Interpretive Interactionism; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1989; pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ryle, G. Collected Papers, Volume 2: Collected Essays 1929–1968; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In The Cultural Geography Reader; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. North Carolina: 2000; Bureau, U.C.: Suitland, MD, USA, 2002.

- U.S. Census Bureau. North Carolina: 2010; Bureau, U.C.: Suitland, MD, USA, 2012.

- Mackun, P. Population Distribution and Change: 2000 to 2010; U.S. Census Bureau: Suitland, MD, USA, 2011.

- Tippett, R. Visualizing Neighborhood Change, 2000 to 2010. Carolina Demography. 2014. Available online: https://www.ncdemography.org/2014/03/31/visualizing-neighborhood-change-2000-to-2010/ (accessed on 23 August 2014).

- Peters, K. City of Raleigh. Available online: http://www.northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/13/entry (accessed on 23 August 2014).

- CityOfRaleigh. Mordecai Historic Park History. Available online: https://cityofraleigh0drupal.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/drupal-prod/COR24/mordecai-historic-park-history-information.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2014).

- Cross, D. The 5 Best Neighborhoods in Raleigh. Available online: https://www.movoto.com/blog/homeownership/the-5-best-neighborhoods-in-raleigh/ (accessed on 23 August 2014).

- Jorgensen, A.; Keenan, R. (Eds.) Urban Wildscapes; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment, 2nd ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Little, S.; Rice, A. Considering Autonomous Exploration in Healthy Environments: Reflections from an Urban Wildscape. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211867

Little S, Rice A. Considering Autonomous Exploration in Healthy Environments: Reflections from an Urban Wildscape. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):11867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211867

Chicago/Turabian StyleLittle, Sarah, and Art Rice. 2021. "Considering Autonomous Exploration in Healthy Environments: Reflections from an Urban Wildscape" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 11867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211867

APA StyleLittle, S., & Rice, A. (2021). Considering Autonomous Exploration in Healthy Environments: Reflections from an Urban Wildscape. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211867