Exploring the Use of Fitbit Consumer Activity Trackers to Support Active Lifestyles in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

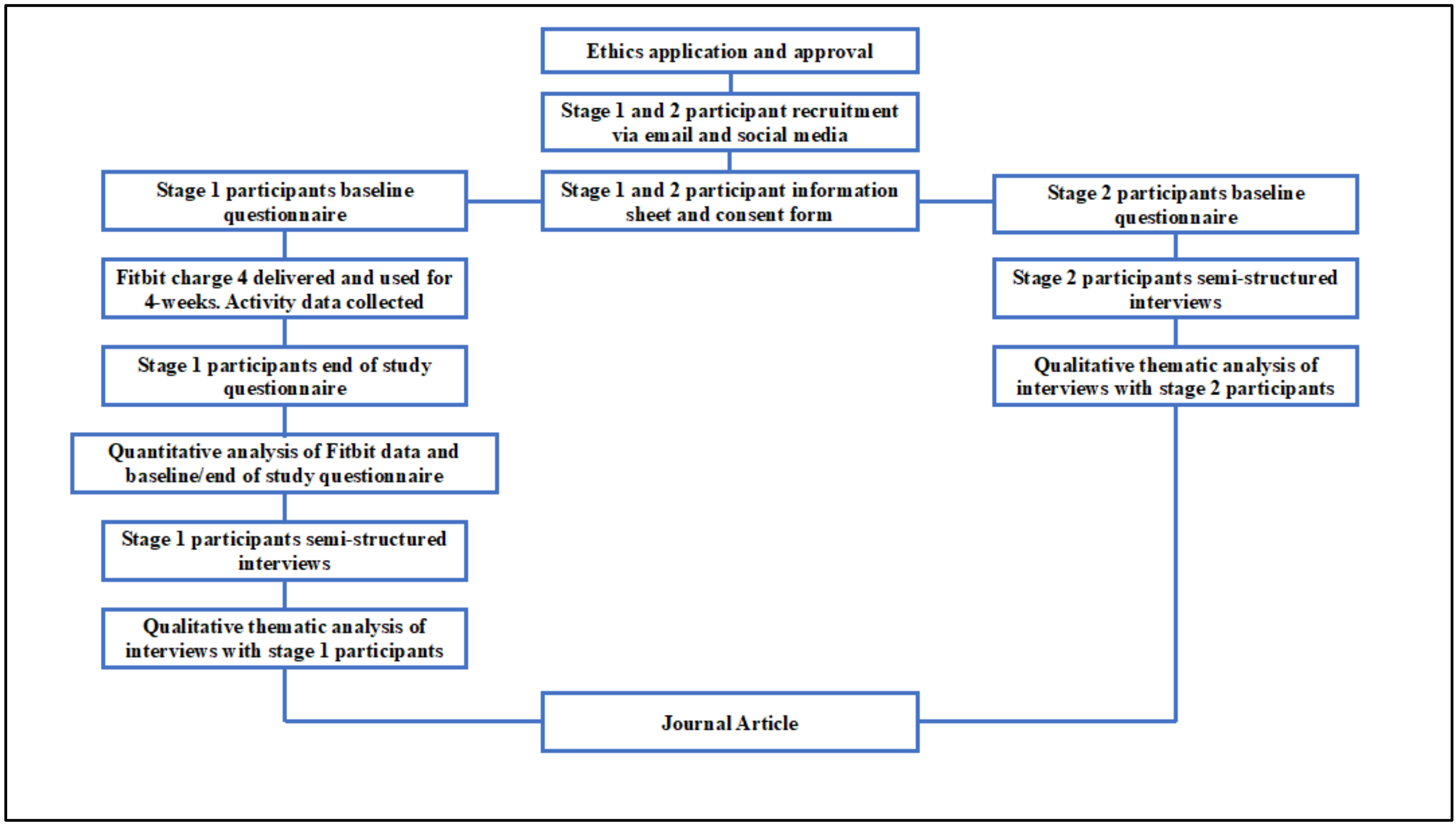

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Stage 1

2.2.2. Stage 2

2.3. Procedure

Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Stage 1—Adults Diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes

3.2. Quantitative Analysis

3.2.1. Participants Fitbit Data

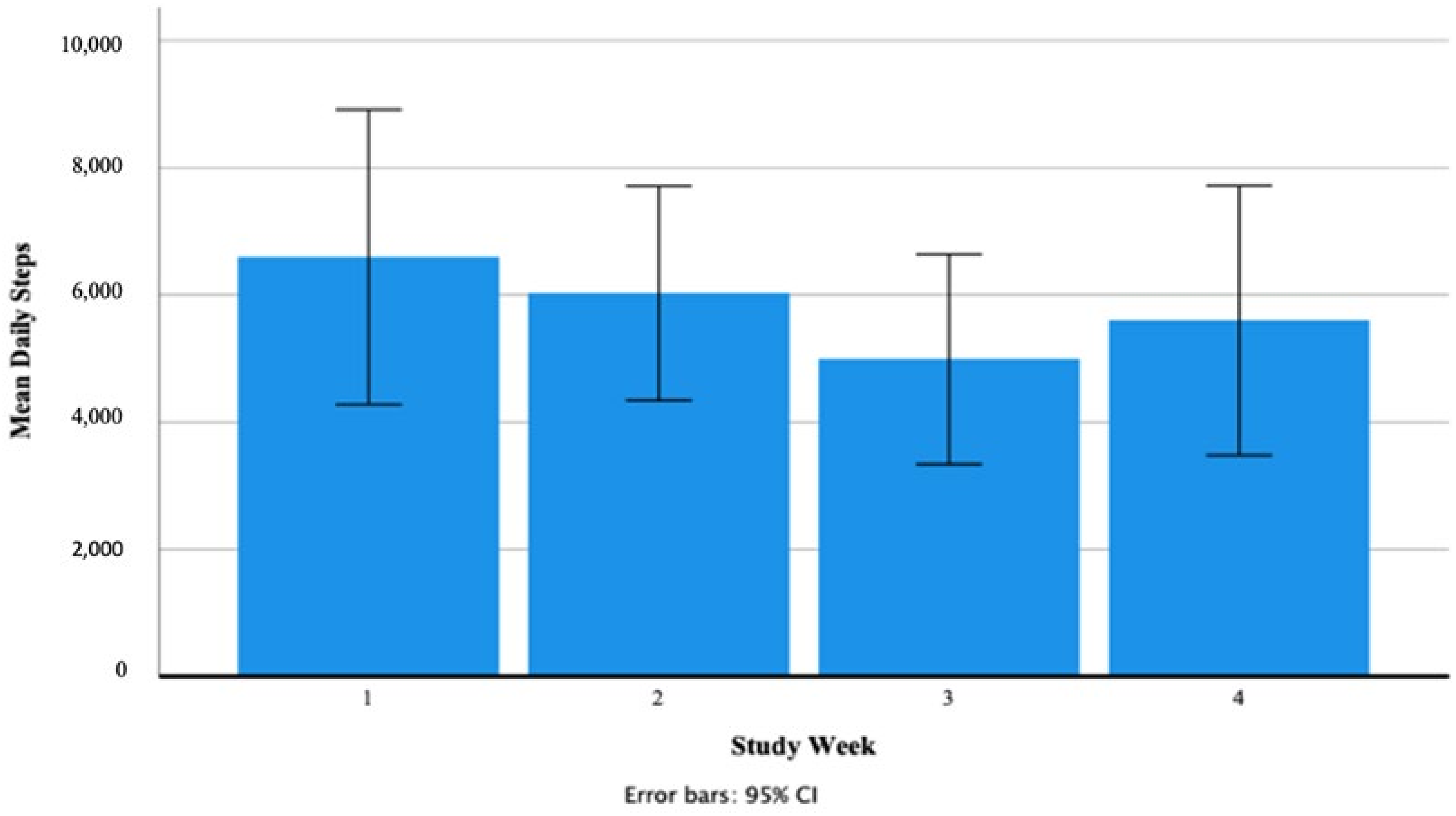

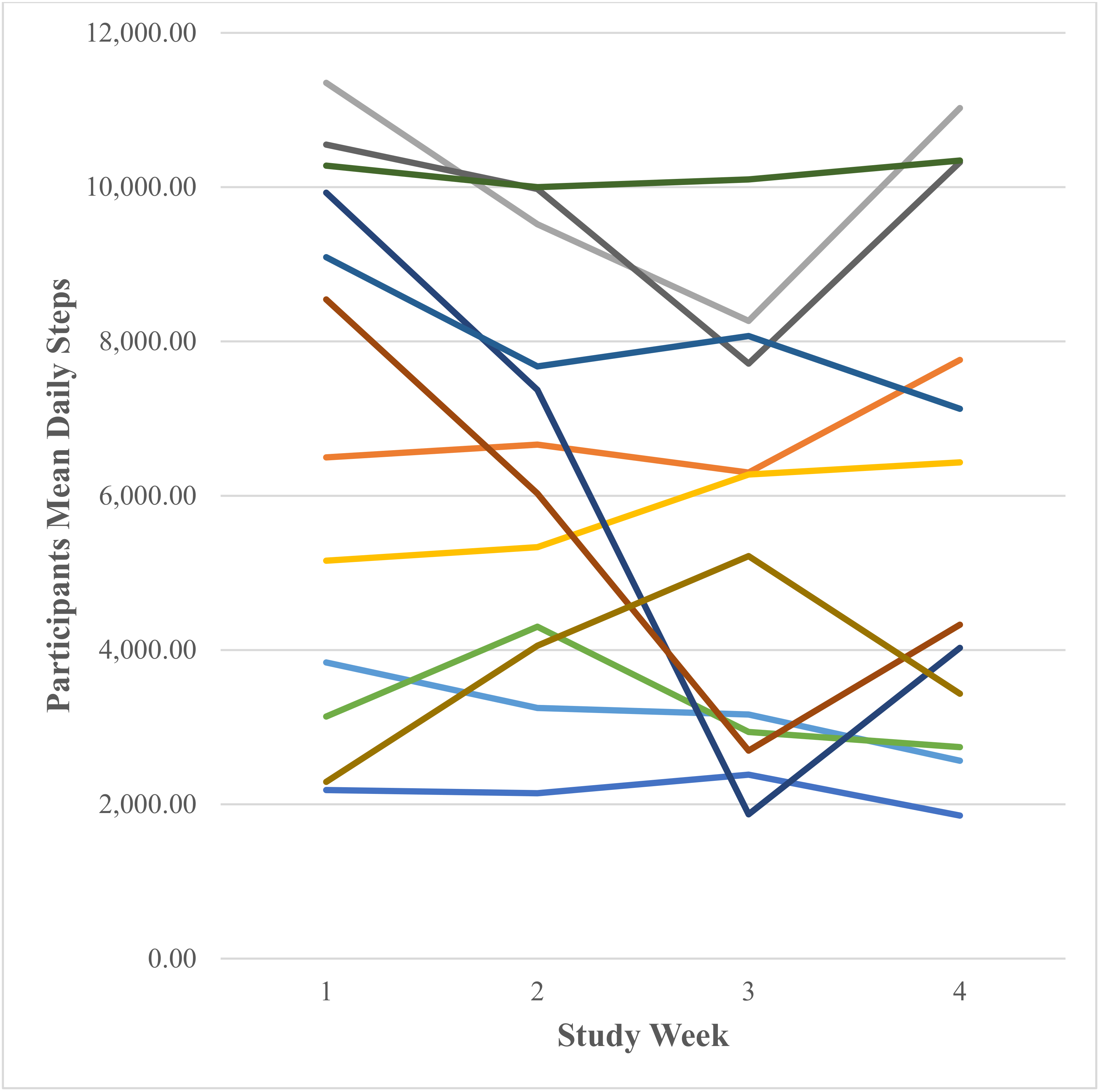

Daily Steps (Number Taken)

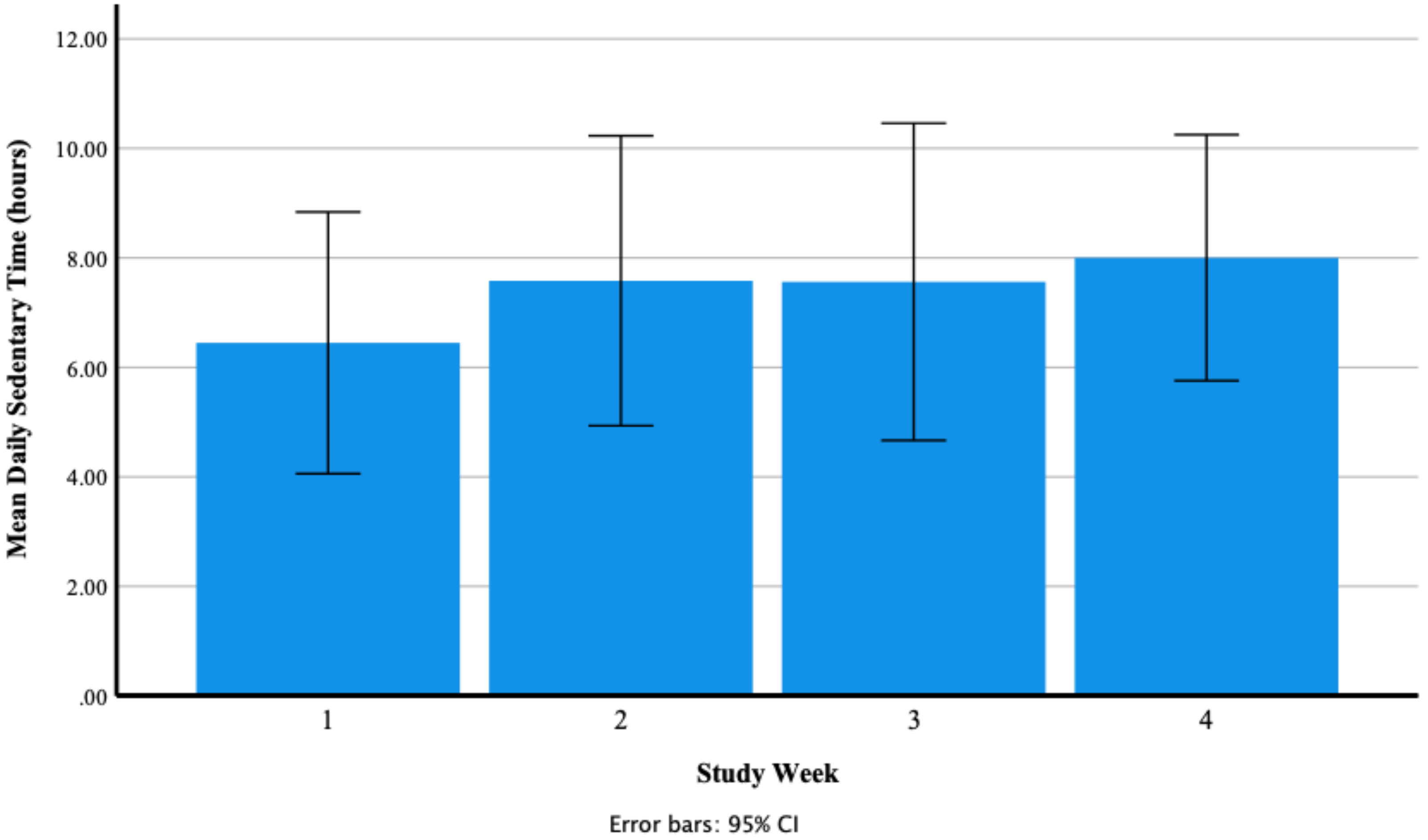

Daily Sedentary Time (Hours)

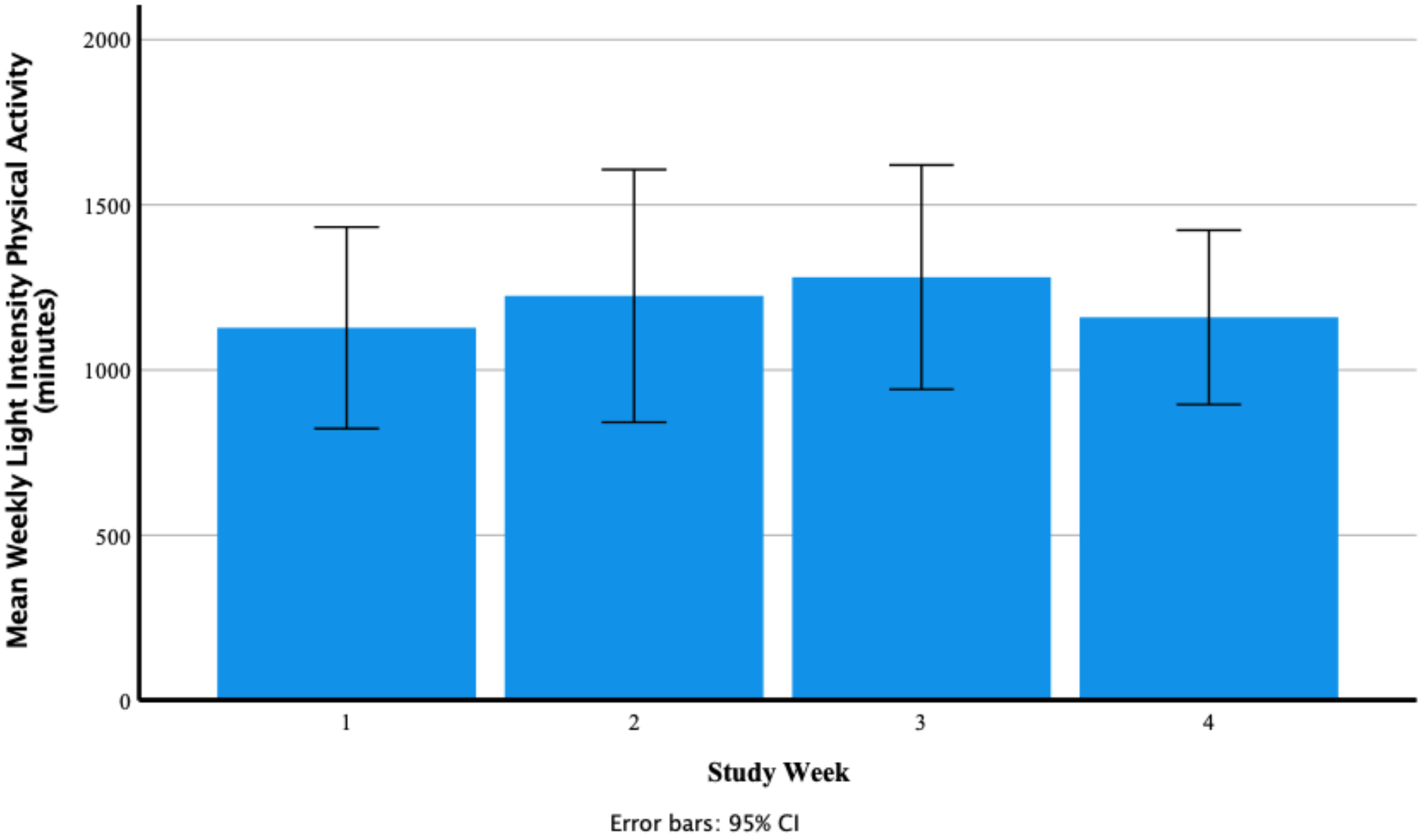

Weekly Light Intensity Physical Activity (Minutes)

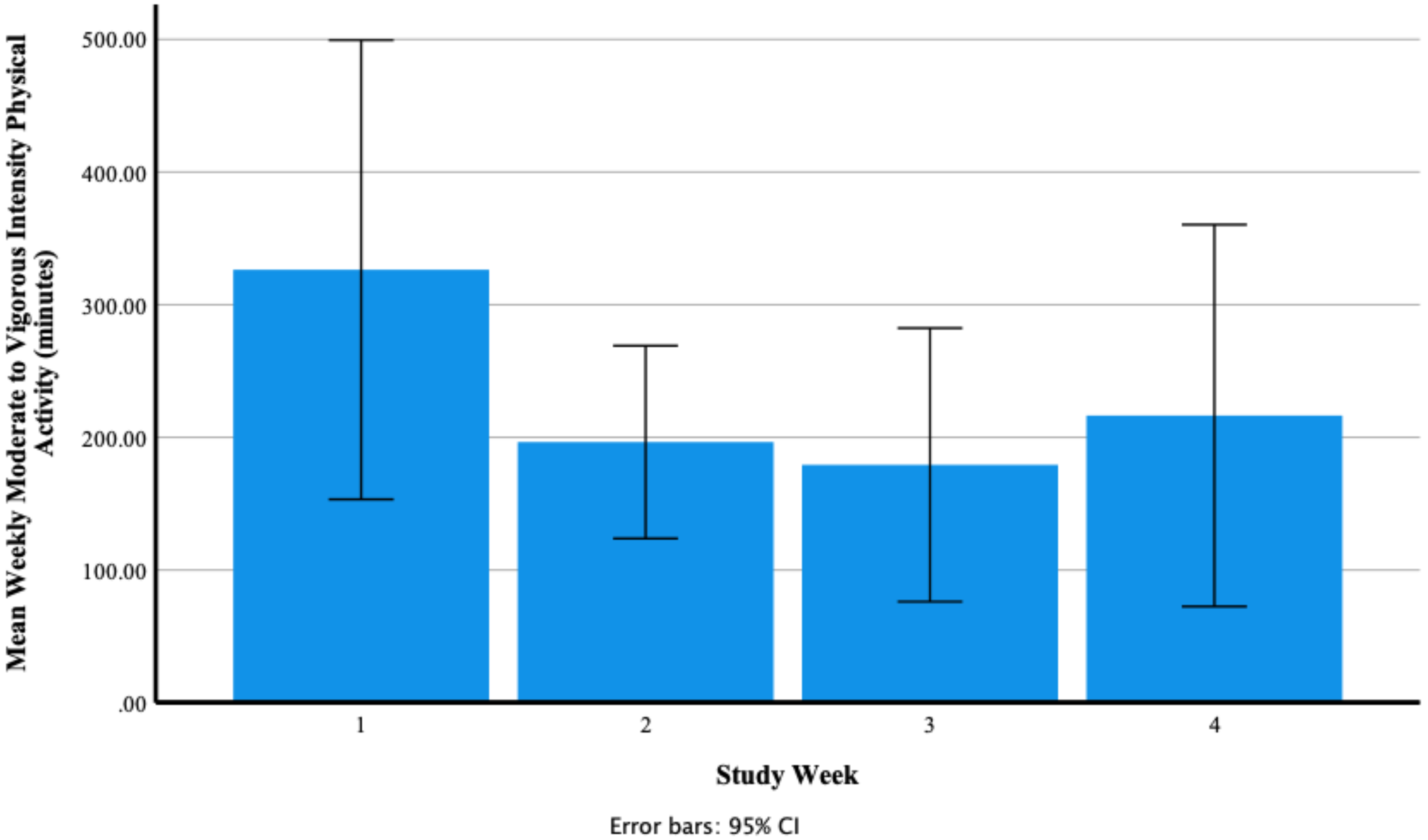

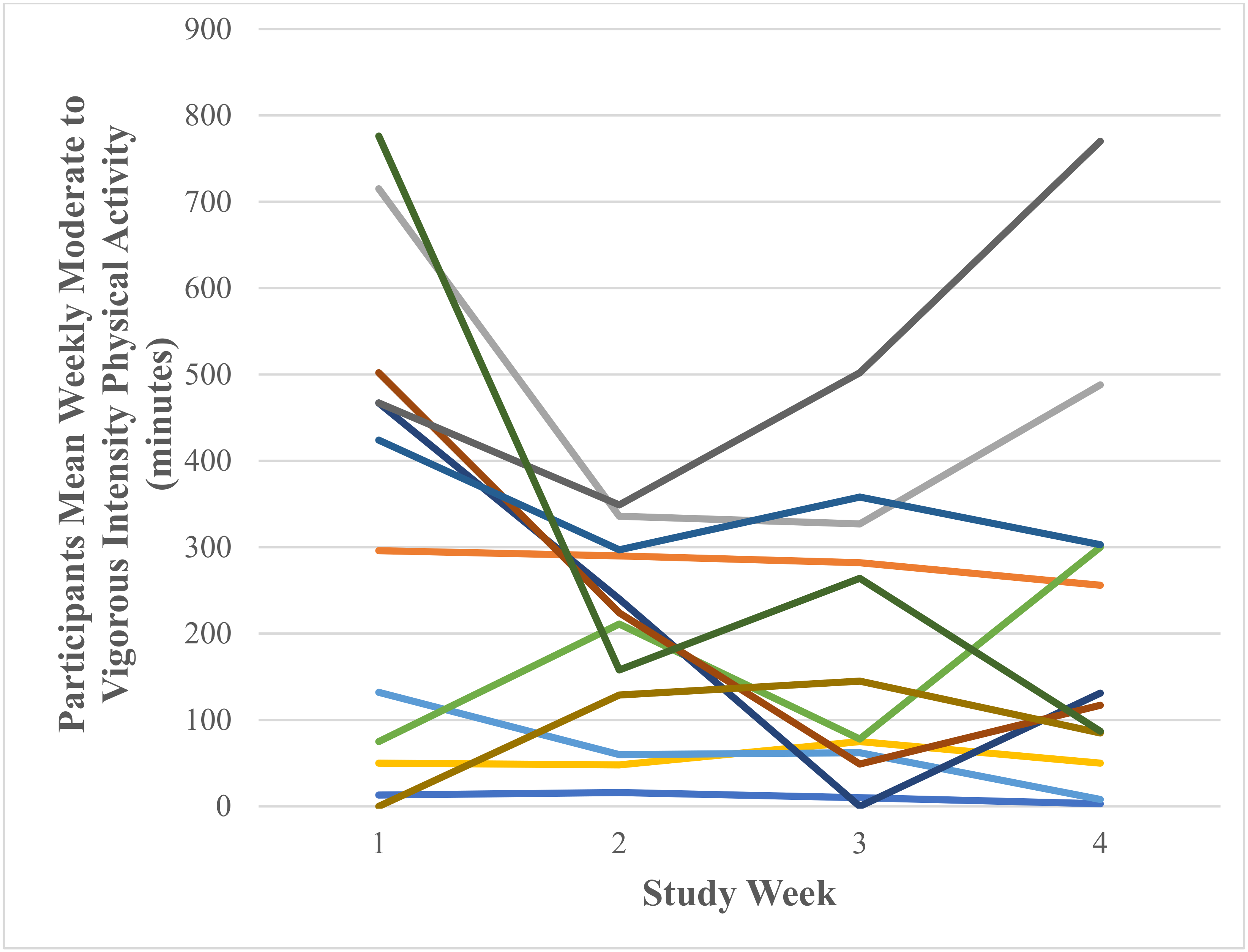

Weekly Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity (Minutes)

3.2.2. Participant Baseline and End of Study Questionnaires

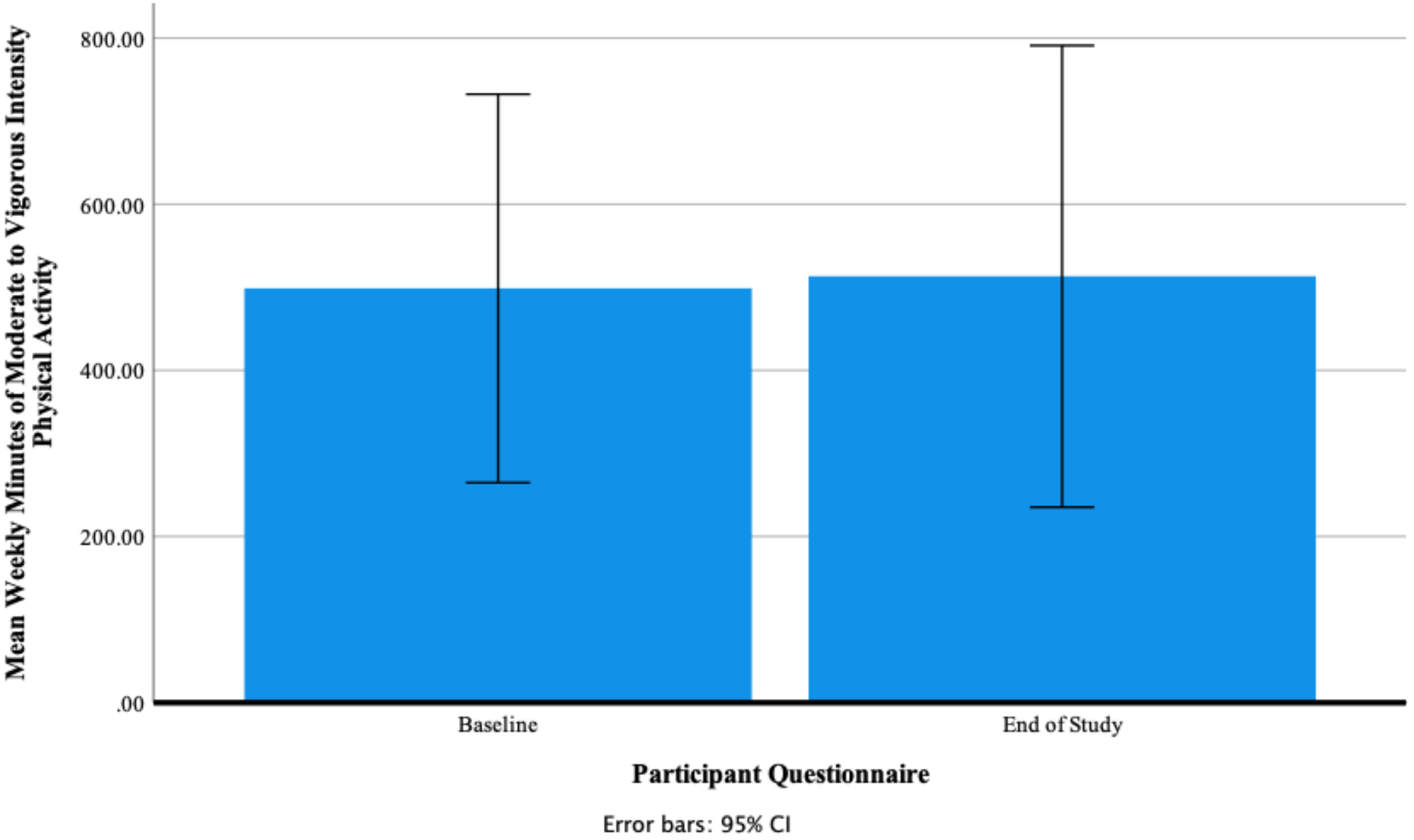

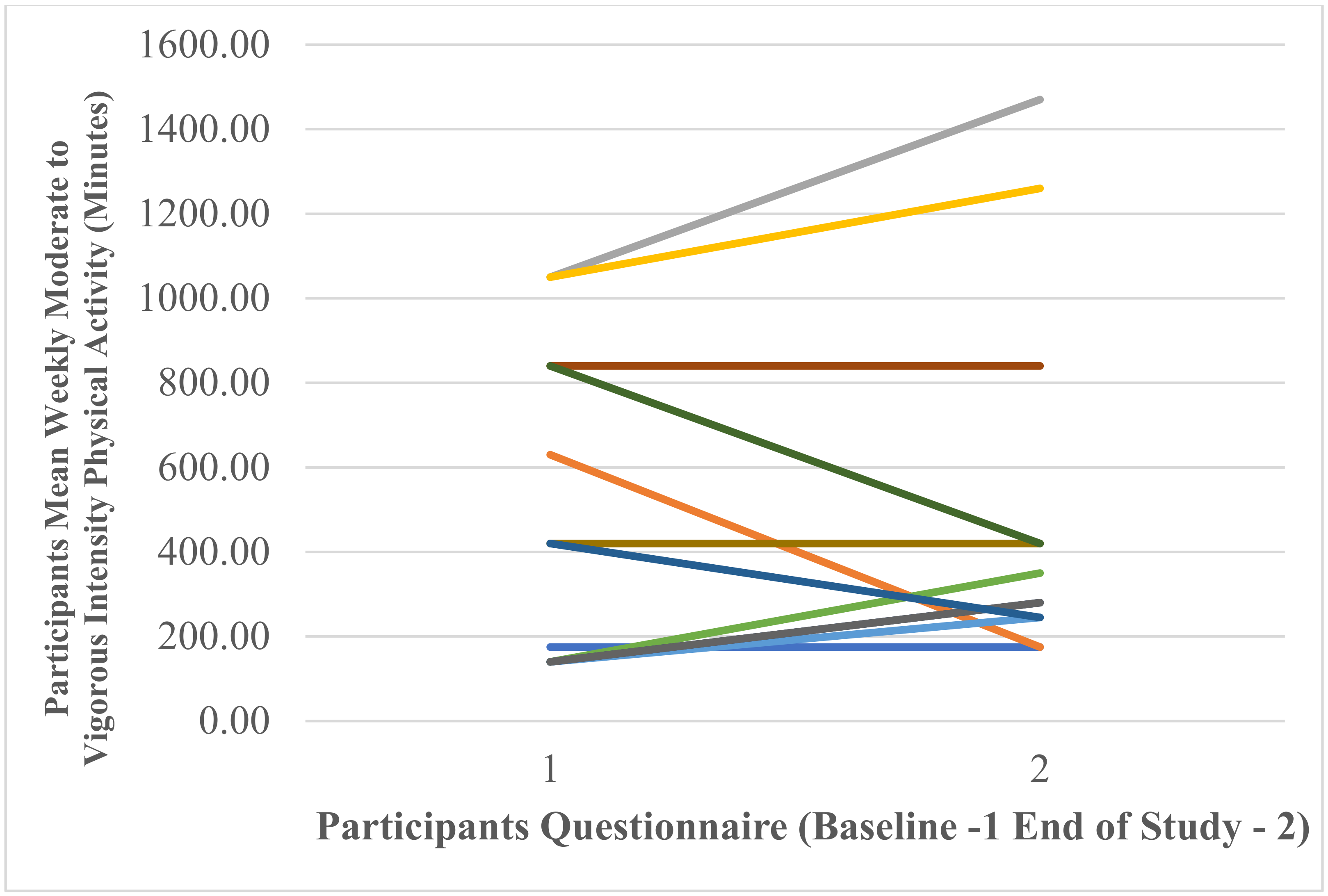

Participants’ Self-Reported Mean Weekly Minutes of Moderate- to Vigorous-Intensity Physical Activity

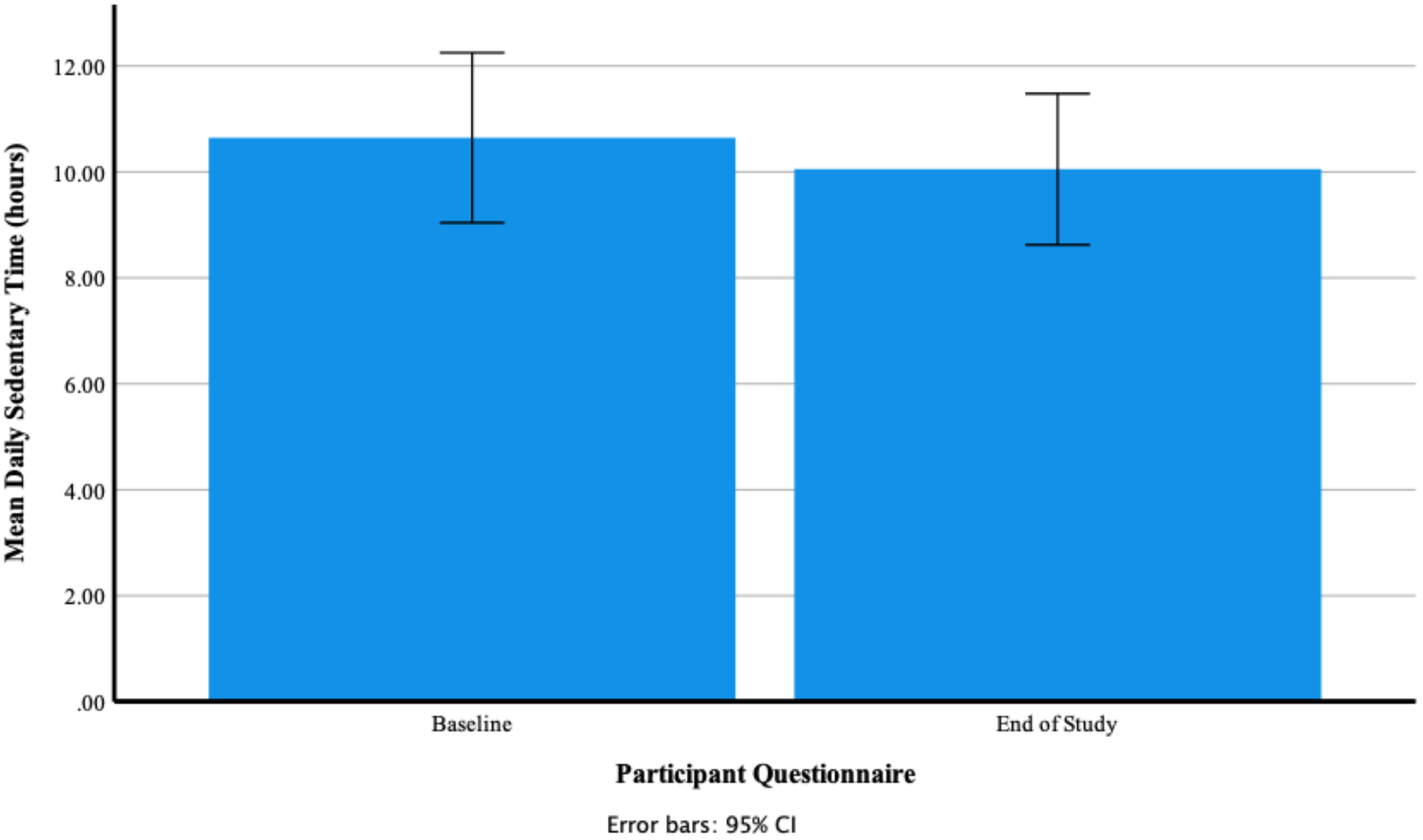

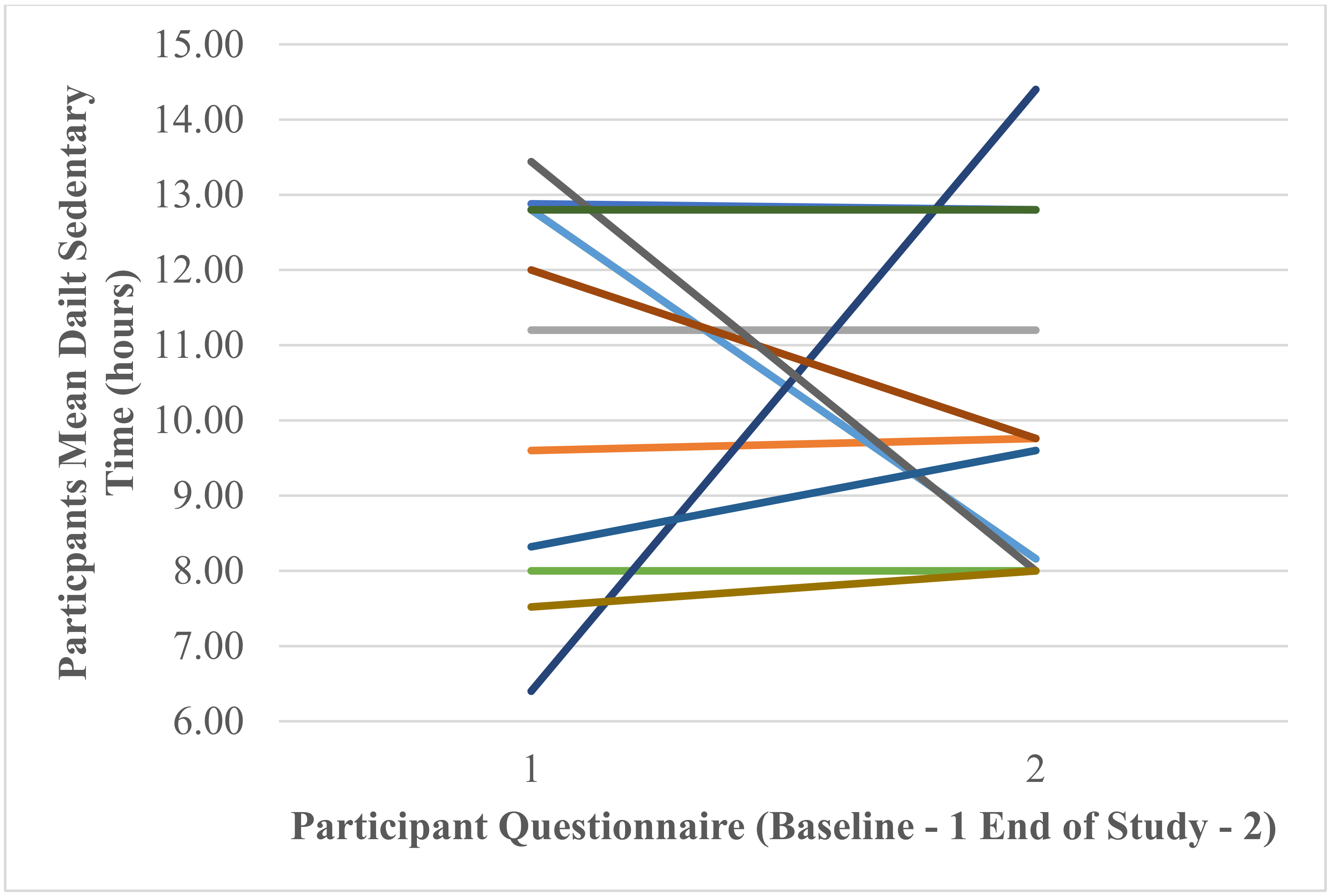

Participants’ Self-Reported Mean Daily Hours of Sedentary Time

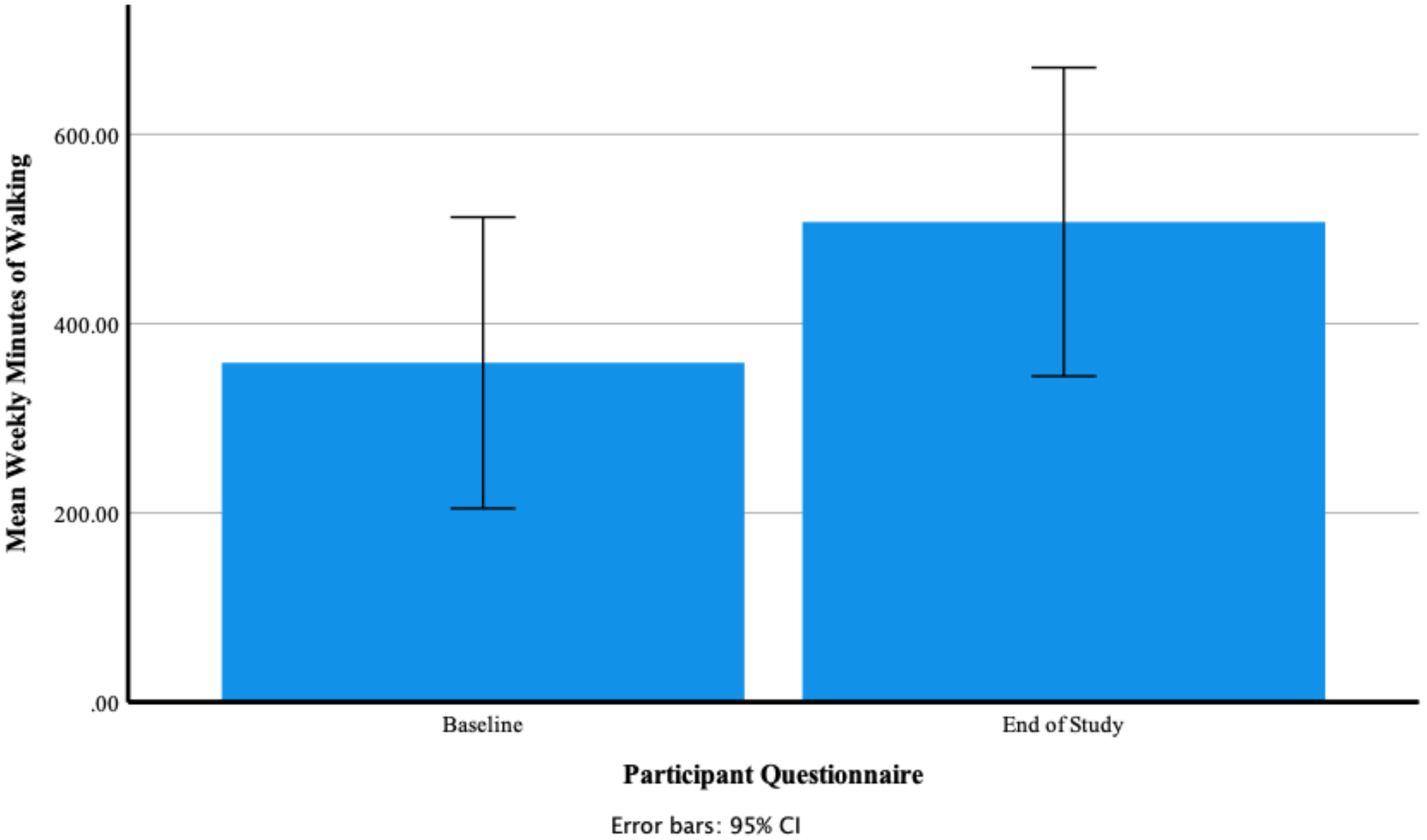

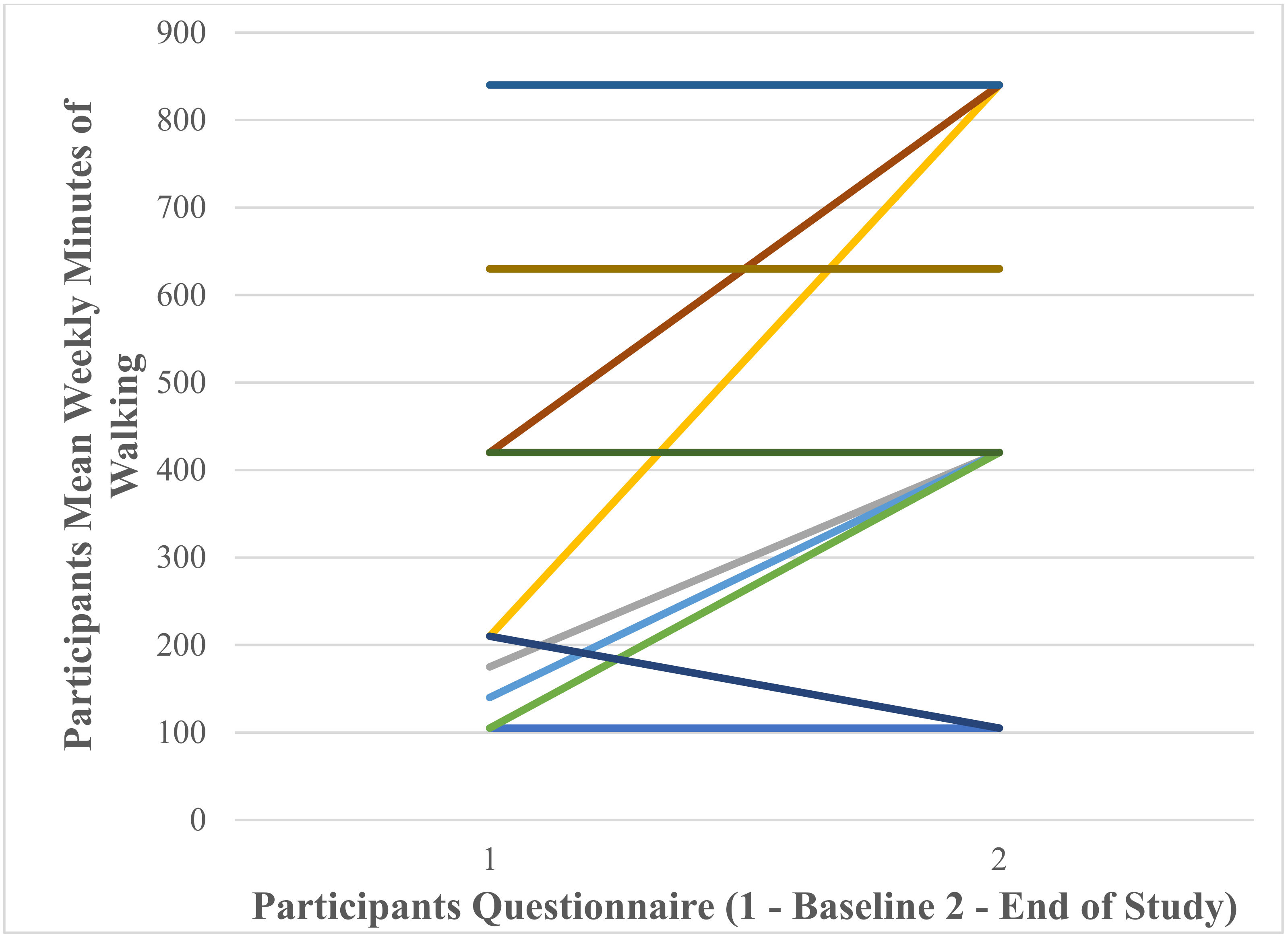

Participants’ Self-Reported Mean Weekly Minutes of Walking at Baseline and End of Study

3.3. Qualitative Analysis

3.4. Stage 2—Health Care and Fitness Professionals

3.4.1. Participants Baseline Demographic Data

3.4.2. Qualitative Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Stage 1—Adults Diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes

4.1.1. Quantitative Analysis

4.1.2. Qualitative Analysis

4.2. Stage 2—Health Care and Fitness Professionals

Qualitative Analysis

4.3. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 9th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Definition and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intermediate Hyperglycemia. 2006. Available online: https://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/Definition%20and%20diagnosis%20of%20diabetes_new.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- McArdle, W.D.; Katch, F.I.; Katch, V.L. Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition, & Human Performance, 6th ed.; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007; Volume 6, pp. 441–442. [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes UK. New Stats People Living with Diabetes. 2019. Available online: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/about_us/news/new-stats-people-living-with-diabetes (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Baena-Díez, J.; Peñafiel, J.; Subirana, I.; Ramos, R.; Elosua, R.; Marín-Ibañez, A.; Grau, M. Risk of cause-specific death in individuals with diabetes: A competing risks analysis. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1987–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caspersen, C.; Powell, K.; Christenson, G. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness: Definitions and Distinctions for Health-Related Research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines; HMSO: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Fernhall, B.; Regensteiner, J.G.; Blissmer, B.J.; Rubin, R.R.; Braun, B. Exercise and Type 2 Diabetes: The American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: Joint position statement executive summary. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 2692–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Umpierre, D.; Ribeiro, P.A.B.; Kramer, C.K.; Leitao, C.B.; Zucatti, A.T.N.; Azevedo, M.J.; Schaan, B.D. Physical Activity Advice Only or Structured Exercise Training and Association with HbA1c Levels in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2011, 305, 1790–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Delevatti, R.S.; Bracht, C.G.; Lisboa, S.D.C.; Costa, R.R.; Marson, E.C.; Netto, N.; Kruel, L.F.M. The Role of Aerobic Training Variables Progression on Glycemic Control of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sports Med. Open 2019, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennerly, A.; Kirk, A. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour of adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Pract. Diabetes 2018, 35, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Saunders, T.J.; Carson, V.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN)—Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dempsey, P.C.; Larsen, R.N.; Sethi, P.; Sacre, J.W.; Straznicky, N.E.; Cohen, N.D.; Cerin, E.; Lambert, G.W.; Owen, N.; Kingwell, B.A.; et al. Benefits for Type 2 Diabetes of Interrupting Prolonged Sitting with Brief Bouts of Light Walking or Simple Resistance Activities. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 964–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sardinha, L.B.; Magalhães, J.P.; Santos, D.A.; Júdice, P.B. Sedentary Patterns, Physical Activity, and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Association to Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Avery, L.; Flynn, D.; van Wersch, A.; Sniehotta, F.F.; Trenell, M.I. Changing Physical Activity Behavior in Type 2 Diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2681–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matthews, L.; Kirk, A.; Mutrie, N. Insight from health professionals on physical activity promotion within routine diabetes care. Pract. Diabetes 2014, 31, 111–116e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, D.B.; Fellner, K.D.; Frank, M.; Small, M.; Hetherington, R.; Slater, R.; Daneman, D. Evaluation of an Online Education and Support Intervention for Adolescents with Diabetes. Soc. Work. Health Care 2012, 51, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, S.G.; Brillante, M.; Allardice, B.; Conway, N.; McAlpine, R.R.; Wake, D.J. My Diabetes My Way: Supporting online diabetes self-management: Progress and analysis from 2016. Biomed. Eng. Online 2019, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- My Diabetes My Way. My Diabetes My Way Newsletter for July 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.mydiabetesmyway.scot.nhs.uk/ContentNews.aspx?id=1117#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Coda, A.; Sculley, D.; Santos, D.; Girones, X.; Acharya, S. Exploring the Effectiveness of Smart Technologies in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2018, 12, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lim, S.; Kang, S.M.; Kim, K.M.; Moon, J.H.; Choi, S.H.; Hwang, H.; Jang, H.C. Multifactorial intervention in diabetes care using real-time monitoring and tailored feedback in type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2016, 53, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, M.S.; Cooper, B.A.; Park, L.G.; Padash, S.; Arai, S. A Feasible and Efficacious Mobile-Phone Based Lifestyle Intervention for Filipino Americans with Type 2 Diabetes: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Diabetes 2017, 2, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Evenson, K.R.; Goto, M.M.; Furberg, R.D. Systematic review of the validity and reliability of consumer-wearable activity trackers. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shorten, A.; Smith, J. Mixed methods research: Expanding the evidence base. Evid. Based Nurs. 2017, 20, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Oja, P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sparkes, A.; Smith, B. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, J.; Codern-Bové, N.; Zomeño, M.; Lassale, C.; Schröder, H.; Grau, M. Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the COMPASS mobile app: A citizen science project. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Number | Gender | Age (Years) | Diabetes Duration (Years) | Weight (kg) | Height (m) | BMI | Blood Glucose (HbA1c %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 77 | 9 | 104.0 | 1.88 | 29.5 | 7.8 |

| 2 | Male | 70 | 12 | 87.4 | 1.93 | 23.4 | 5.2 |

| 3 | Male | 52 | 6 | 100.0 | 1.93 | 26.8 | 7.2 |

| 4 | Female | 66 | 11 | 96.0 | 1.70 | 33.2 | 6.5 |

| 5 | Male | 66 | 30 | 103.0 | 1.83 | 30.8 | 5.4 |

| 6 | Male | 46 | 5 | 141.0 | 1.82 | 42.6 | 6.1 |

| 7 | Female | 57 | 1 | 78.0 | 1.60 | 30.5 | 6.0 |

| 8 | Male | 51 | 17 | 112.5 | 1.88 | 31.9 | 6.3 |

| 9 | Female | 56 | 7 | 87.0 | 1.60 | 34.0 | 7.9 |

| 10 | Male | 69 | 16 | 80.0 | 1.73 | 26.8 | 7.5 |

| 11 | Male | 53 | 2 | 97.0 | 1.83 | 29.0 | 12.0 |

| 12 | Female | 42 | 10 | 82.0 | 1.63 | 30.8 | 7.0 |

| Mean | 58.8 | 10.5 | 97.3 | 1.78 | 30.8 | 7.1 |

| Main Themes (n = 7) | Sub-Themes (n = 40) |

|---|---|

| Current delivery of physical activity advice within type 2 diabetes health care (158) |

|

| Integrated elements of type 2 diabetes health care (14) |

|

| Data security and management (36) |

|

| Personalisation of type 2 diabetes physical activity support (45) |

|

| Use of Fitbit as a motivational and goal setting tool (48) |

|

| Users preferred Fitbit functions (57) |

|

| Barriers to Fitbit use (7) |

|

| Main Theme | Data Analysis |

|---|---|

| Current delivery of physical activity advice within type 2 diabetes health care | During interviews participants discussed how physical activity was currently promoted within their type 2 diabetes health care. |

| The lack of physical activity support and the impact upon the health of participants was highlighted as a concern. | |

| “If they had told me how much exercise impacted upon my blood glucose levels would have helped but they only skimmed over the subject. I have noticed that days when I don’t exercise my glucose levels rise” | |

| The majority of participants stated that physical activity advice within their type 2 diabetes health care was limited. The advice was mainly promoted, by a health care professional, through a short discussion around present activity levels and the importance of being more active. Detailed analysis of patient’s activity was seldom undertaken, and follow-up exercise support was not offered. | |

| “I have been diabetic for about 10 years and only had a limited amount of advice regarding physical activity” | |

| “In terms of when I was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes the only thing that I was told was to try and increase any level of activity” | |

| Participants stated that the main focus of their type 2 diabetes care was around medication, diet and blood glucose levels. Physical activity was seldom discussed in detail and was not regularly promoted during visits to clinics. | |

| “More time is spent discussing medication, blood glucose readings and diet” | |

| “The support needs to cover everything including activity, medication and diet” | |

| During type 2 diabetes consultations with a health care professional detailed analysis of the patient’s physical activity was seldom undertaken. During these meetings the needs of patients and their preferred choice of exercise were never analysed in detail. | |

| “They have never actually drilled down into how much of the time I am actually spending being active” | |

| “I do also have the occasional session with my doctors practice nurse. She has told me to keep active. Other than these short discussions I have received nor further advice regarding physical activity” | |

| Two participants, who exercised on a regular basis and were knowledgeable of the benefits for their type 2 diabetes, found that physical activity advice available through different diabetes support sources conflicted. In their opinion such conflicting information caused confusion and would be more difficult to understand for those patients who were less active. | |

| “There was even a conflicted with the advice that Diabetes UK and NHS gave especially in relation the physical activity” | |

| Most of the participants said that physical activity advice was most commonly communicated verbally at only a superficial level by their health care professional. In the majority of cases exercise promotion was delivered by either a diabetes practice nurse or a clinic practice nurse. | |

| “This has been verbally given by the practice nurse. Who is also a diabetic practice nurse” | |

| “The practice nurse did inform me verbally to be more active but that was just a short discussion” | |

| Three participants declared that within their type 2 diabetes health care practice additional physical activity support was provided beyond just a verbal discussion. Two of the patients were offered free access to a local authority sports facility including exercise advice from a qualified personal trainer. One participant said that in their clinic a walking group had been established for those diagnosed with type 2 diabetes with the aim to increase levels of physical activity. Both of these options proved to be popular with patients. | |

| “We were provided with free access to the community gym and health centre by the local nursing team” | |

| “I was also signed up for a diabetes walking support group through my GP …” | |

| The regularity of physical activity promotion varied between participants. For some physical activity was discussed briefly during each 3–4 monthly diabetes clinic. For the remainder physical activity had seldom been discussed since first diagnosis 10–11 years earlier. | |

| “I was diagnosed about 11 years ago and other than the occasional reminder to be active there has been no further advice or support” | |

| “I get a regular 4-month health check from a nurse in the local GP practice. She usually asks about my physical activity and depending on the circumstances she may nag a bit about you know you should be exercising” | |

| A few participants thought that time pressures on health care staff was the main reason physical activity received only limited promotion. For staff to go beyond a brief discussion would require significantly more time and resources. | |

| “…the staff just don’t have the time and their focus is more on my glucose levels and medication” | |

| Integrated elements of type 2 diabetes health care | Participants discussed the need to integrate all elements, including physical activity, of type 2 diabetes health care into a single support package. |

| Five participants, who were registered with the MY Diabetes My Way programme, suggested that they would like to see their Fitbit data downloaded onto the system database and someone provide them with personalised physical activity analysis and feedback. | |

| “It would be good if I could input my activity data into the My Diabetes My Way system and it gave me some feedback along the lines of well-done you are doing well or you need to do more of a specific activity” | |

| “This would allow for a far more personalised approach and probably get people more active” | |

| The availability and role of type 2 diabetes health care support technology was mentioned by a few of the participants. In the experience of these patient’s available technology was only capable of undertaking a single specific task such blood glucose monitors. Participants desired for a single item of technology that could measure and provide feedback for blood glucose levels, physical activity and diet. | |

| “It would be great having an all-round support package that combined both physical activity and diet. This is not available at the moment” | |

| “Another good thing would be the development of a combined activity and glucose monitor. I would find this very useful during my day-to-day life” | |

| Data security and management | All participants indicated that they would be happy to share their data from a Fitbit activity tracker with NHS information technology systems and directly with health care professionals. Participants trusted data security, storage and management of systems available within the health care sector. The use of Fitbit data was also supported by patients if it would lead to increased physical activity support. |

| “I have no worries about sharing my activity data with my doctor, nurse or on the My Diabetes My Way system” | |

| “I would be more than happy for my Fitbit data to be linked into a health care system especially if being used to support me” | |

| Personalisation of type 2 diabetes physical activity support | The majority of participants indicated that they would like to receive additional physical activity support from health care professionals that was personalised and focused on their exercise needs and lifestyle. |

| “The care team could spend more time going over this with me and make it more personalised” | |

| Additional physical activity support from health care staff was desired by most of the participants. Suggested improvements included more discussion time, greater analysis of present activity levels and development of detailed exercise programmes. | |

| “Developing a personalised training plan for users would be a great addition. This could be set around the users preferred choice of activity i.e., walking or cycling. This support could also include information on the benefits of physical activity for type 2 diabetes” | |

| Physical activity support from non-health care sources was favoured by a few of the participants. Such support included family/friends, diabetes support groups and community-based walking groups. | |

| “Yeah I think that I am quite fortunate that I have my husband and children to support me” | |

| “I would like to explore diabetes support groups where I could share my experiences with others” | |

| Use of Fitbit as a motivational and goal setting tool | Most participants highlighted the motivational and goal setting impact of the Fitbit Charge 4 activity tracker during their trial of the device over a 4 week period. |

| The ability of participants to record and review their daily activity proved popular and motivated some to be more active. | |

| “I was taking more steps than I thought, and this certainly motivated me to get out more” | |

| “The Fitbit has encouraged me to get out walking more which I have really enjoyed” | |

| As some participants became more familiar with the Fitbit functions they started to develop their own physical activity goals. Reaching these goals produced a sense of achievement for users. | |

| “I set my own little goals and the Fitbit was very good for doing this. Setting these goals and reaching them made me feel good about myself” | |

| For half of participants the Fitbit allowed them to analysis their activities in more detail. Beyond the step counting function users found the heart rate monitor provided feedback on the intensity of their physical activity, which encouraged them to increase the pace during walks. | |

| “Combing both of these functions was great for me as I could measure the number of steps but also see how hard I was working. In relation to the heart rate, I found this very reassuring to see how hard I was working” | |

| Users preferred Fitbit functions | All participants discussed their experience of using the Fitbit Charge 4 activity tracker and the functions they found useful in support of an active lifestyle. |

| The most popular Fitbit function with most users was the step counter followed by the distance moved element. The step and distance functions were easy to understand without the need for further advice or support and complemented the most popular activity of walking. | |

| “I found the steps counting function very good. I was able to see what I was doing when out for my walks” | |

| Some users found the Fitbit heart rate monitor useful both from a novelty perspective and a tool to provide feedback on exercise intensity. | |

| “In relation to the heart rate, I found this very reassuring to see how hard I was working” | |

| During interviews some of the participants suggested that they would like a health care professional to incorporate the use of Fitbit functions within their type 2 diabetes treatment with a view to increasing activity levels. | |

| “I think it would a good thing if my diabetes nurse could access my data and then we could sit done and chat about it and how to improve things or just keep me active” | |

| A small number of participants found both the sleep and nutrition Fitbit functions useful though these did not form part of the study aims. | |

| “I also liked the sleep function. This was good to see the amount and quality of my sleep” | |

| “The calories in and calories out was also interesting” | |

| Barriers to Fitbit use | Barriers to the use of the Fitbit Charge 4 activity tracker were raised by a small number of the participants. One participant initially had difficulty setting the device up and required support from a family member. Once setup, the participant became more confident in using this new technology. A second participant found the Fitbit too complicated to use without additional support. |

| “I wasn’t sure at the beginning. My husband had to set it up … but as I got used to it I really found it motivating” | |

| “I couldn’t understand some of the functions which were too complicated for me” |

| Main Themes (n = 6) | Sub-Themes (n = 32) |

|---|---|

| Present promotion of physical activity within type 2 diabetes health care (151) |

|

| Data security and management (8) |

|

| Fitbit functionality (29) |

|

| Fitbit health care barriers (8) |

|

| Future use of Fitbit within type 2 diabetes health care (93) |

|

| Improving physical activity promotion (74) |

|

| Main Theme | Data Analysis |

|---|---|

| Present promotion of physical activity within type 2 diabetes health care | Participants provided feedback in relation to the present promotion of physical activity within type 2 diabetes health care. Medical staff in general stated that physical activity promotion within the NHS was limited and usually involved a short lifestyle discussion with the patient. Time constraints on health care staff was identified as a major barrier to promotion. Where physical activity advice was provided medical professionals found that this was ignored by patients and especially those already inactive. A few health care staff provided additional support in the form of self-help groups and targeted activity programmes. These sessions tended to be organised out with the normal working day of the clinician and were developed through a personal interest in type 2 diabetes. Generally, the promotion of physical activity is delivered by either a clinics practice nurse or a specialist diabetes nurse. The main focus of physical activity promotion is presently on prevention rather than treatment. Activity trackers are occasionally discussed with patients but never prescribed. |

| “We have nearly 800 diabetic patients under our care and it is impossible to see them in detail” | |

| “When you do give them advice they generally do not take it seriously” | |

| “One of my colleagues has started a diabetes project to support patients and part of this was running a support and walking group” | |

| “We just don’t have the time to spend on support packages. The promotion is usually a short lifestyle discussion with the patient” | |

| Data security and management | All health care and fitness professionals were satisfied that the security and management of Fitbit data shared with NHS information systems and medical staff would be used appropriately and stored securely. The need to obtain consent from the Fitbit user to store and use their activity data was recommended. Fitbit management participants provided reassurance that their company would not share user data unless consent is obtained from the device owner. |

| “As long as it was shared over a secure confidential system I cannot see this being an issue. At the end of the day the patient will make the final decision” | |

| “Overall security data is stored and managed safely within the NHS. The important element is patient consent” | |

| “If you are clear about what data you are collecting and why you are collecting that data there should be no issue. For patients they can opt in or out of data sharing” | |

| Fitbit functionality | Participants discussed the Fitbit functions and how these could be used to support an active lifestyle in people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. The Fitbit step counting facility was highlighted as the most useful within health care and an easy concept for patients to understand. Health care staff also highlighted the heart rate, nutrition and sleep functions as valuable tools for type 2 diabetes diagnosis and treatment. Fitbit management participants suggested utilising the Fitbit communities function for the establishment of type 2 diabetes support groups and programmes. The communities function allows users to sign up for challenges and join or setup support groups. The Fitbit premium service (presently £7.99 per month or £79.99 per year) was also recommended by Fitbit management participants as a useful physical activity intervention package. The premium service includes personalised activity programmes, motivational games/challenges, in-depth activity and health analysis, exercise workouts and mindfulness support (breathing and relaxation exercises). |

| “… the step count is useful even just as a baseline. 10,000 steps is not achievable for everyone, but it is easier for me to set achievable step goals using these activity trackers” | |

| “For health care professional’s data such as heart rate and sleep patterns are useful. In relation to sleep there are studies that have shown that sleep can effect an individual’s glucose sensitivity. The heart rate is good for measuring a patient’s metabolic rate again an important factor in diabetes” | |

| “The Fitbit app has communities as part of the system. For example, we have just started a partnership programme with Diabetes UK which will hopefully help those that sign up to the specific Diabetes UK community group with help from those that are in the same position” | |

| “There is a Fitbit premium service which users pay for. This takes the users data and analyses it and then makes recommendations for the user. It is person centred” | |

| Fitbit health care barriers | Participants discussed the limitations and barriers to using Fitbit activity trackers within type 2 diabetes health care. The main identified barrier was cost and who should fund the purchase of a device. Medical participants highlighted the limited budgets available to treat patients and the additional financial burden that Fitbit activity trackers would place on resources. If patients were expected to purchase an activity tracker as part of their treatment this could exclude certain individuals from lower income families. A further barrier discussed was the information technology skills of patients which may be limited and require additional support including suitable internet access. |

| “The main negative would be the cost element and who covers this. Not all patients can afford these items” | |

| “I would love to have some to hand out, but our budget would not cover that” | |

| “I think these basic tools are good though they can cause stress for patients as well if they are not confident using technology” | |

| Future use of Fitbit within type 2 diabetes health care | The potential future use of Fitbit activity trackers within type 2 diabetes health care was examined by the interviewees. Medical professionals stated that activity trackers would be a valuable tool to examine patient’s physical activity levels and develop intervention programmes around their needs. Some suggested using Fitbit trackers as a cost-effective physical activity treatment rather than relying on more expensive medications. Fitbit management participants discussed future developments of the device including the ability to provide electrocardiogram readings, measurement of blood glucose levels and production of software capable of providing detailed physical activity analysis. Social prescription was also recommended with pharmacies being a hub for the distribution of activity trackers and provider of physical activity support. It was suggested that social prescription would reduce the pressures on frontline medical services. |

| “I would be interested in developing the use of trackers within my own health care. The feedback would a be a great tool when advising patients” | |

| “Data generated from a Fitbit is a prime example. Such data could be analysed by either a doctor or diabetic nurse and prescribed exercise promoted” | |

| “I know with some of the new products coming out that there is a greater focus on the heart and being able to produce ECG type feedback. We are also looking at the possibility of also developing devices that can measure insulin and glucose levels” | |

| “The ability to build a programme around social prescription that can be used by GP’s or increasingly through migration of services to pharmacies. Giving pharmacies more information and more tools to help them help the local community” | |

| Improving physical activity promotion | The improvement of physical activity promotion within type 2 diabetes health care was explored with participants. Better signposting of physical activity support within the NHS was suggested as this is presently an under used method of treatment. Dedicated physical activity trained staff was also recommended who could develop personalised intervention packages for patients. Further support in the form of specific activity sessions and exercise groups could be established within medical centres. The development and use of tools such as Fitbit’s and behavioural change interventions should be explored so as to allow patients to take greater control of their own lives. Increased use of physical activity prescriptions was suggested which allow health care staff to direct patients to local sports facilities at a reduced access cost. |

| “I think more sign posting direction patients to physical activity services” | |

| “The personalisation of promotion is really important, and this is not widely used within the NHS” | |

| “I expect the GP’s have more access to exercise prescription. For example, free gym or swimming passes” | |

| “Wellbeing groups are also good at supporting behaviour change” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hodgson, W.; Kirk, A.; Lennon, M.; Paxton, G. Exploring the Use of Fitbit Consumer Activity Trackers to Support Active Lifestyles in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111598

Hodgson W, Kirk A, Lennon M, Paxton G. Exploring the Use of Fitbit Consumer Activity Trackers to Support Active Lifestyles in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111598

Chicago/Turabian StyleHodgson, William, Alison Kirk, Marilyn Lennon, and Gregor Paxton. 2021. "Exploring the Use of Fitbit Consumer Activity Trackers to Support Active Lifestyles in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111598

APA StyleHodgson, W., Kirk, A., Lennon, M., & Paxton, G. (2021). Exploring the Use of Fitbit Consumer Activity Trackers to Support Active Lifestyles in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11598. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111598