Childhood Psychological Maltreatment and Depression among Chinese Adolescents: Multiple Mediating Roles of Perceived Ostracism and Core Self-Evaluation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Maltreatment and Adolescent Depression

1.2. The Mediating Role of Perceived Ostracism

1.3. The Mediating Role of Core Self-Evaluation

1.4. The Mediating Roles of Perceived Ostracism and Core Self-Evaluation

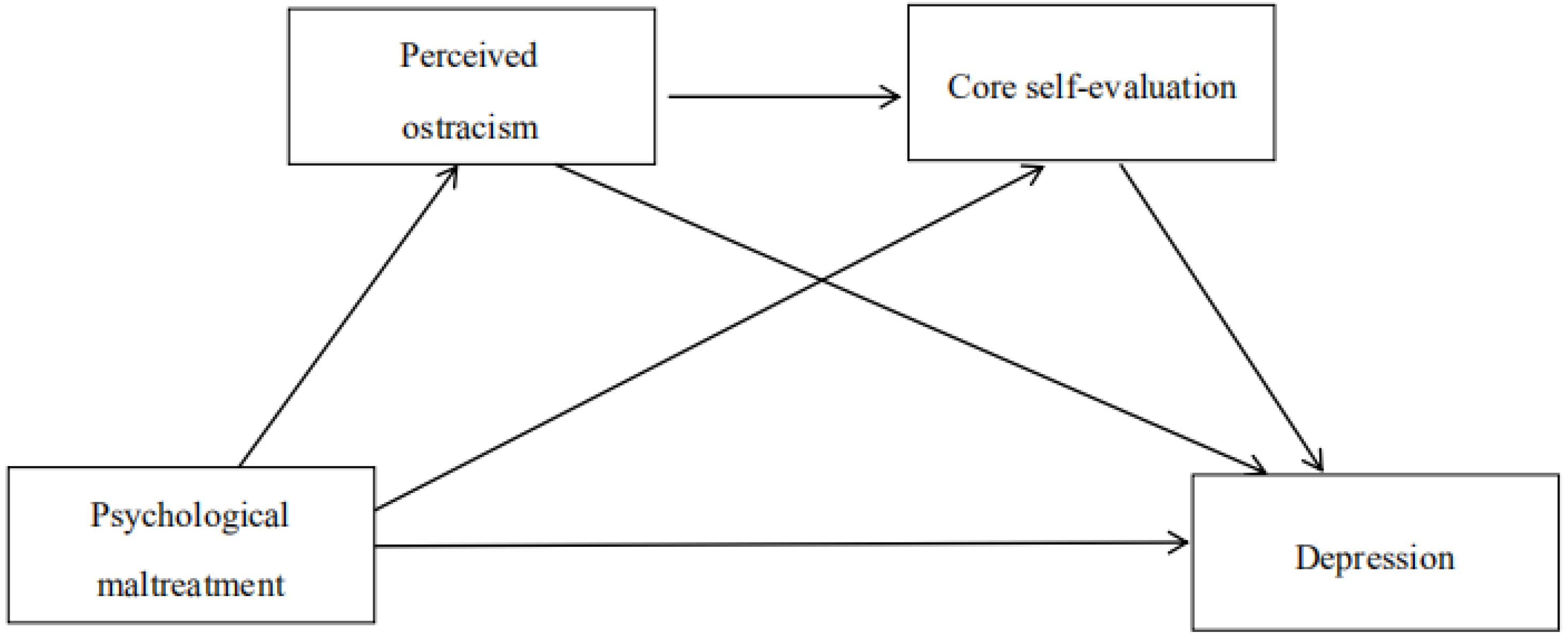

1.5. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Psychological Maltreatment

2.2.2. Perceived Ostracism

2.2.3. Core Self-Evaluation

2.2.4. Depression

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

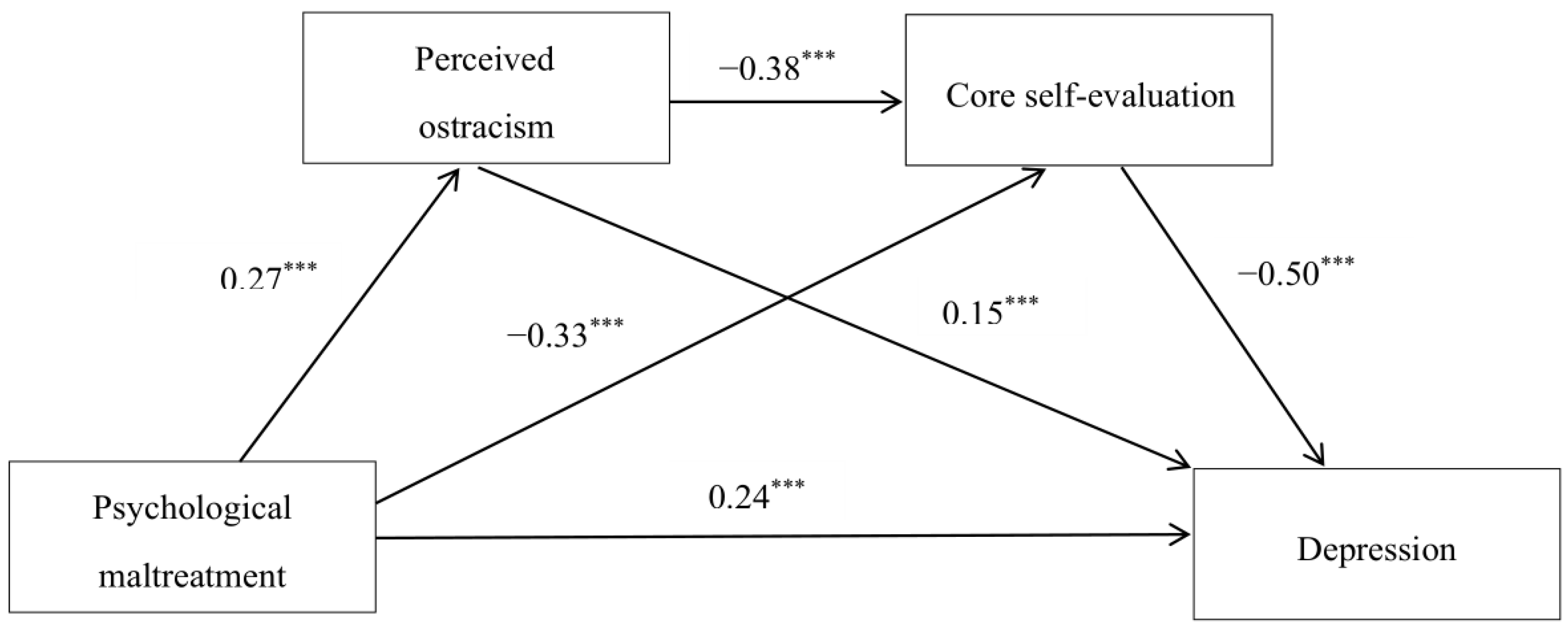

3.2. Multiple Mediating Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. The Mediating Role of Perceived Ostracism

4.2. The Mediating Role of Core Self-Evaluation

4.3. The Mediating Roles of Perceived Ostracism and Core Self-Evaluation

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

4.5. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maughan, B.; Collishaw, S.; Stringaris, A. Depression in childhood and adolescence. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 22, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Windfuhr, K.; While, D.; Hunt, I.; Turnbull, P.; Lowe, R.; Burns, J.; Swinson, N.; Shaw, J.; Appleby, L.; Kapur, N. Suicide in juveniles and adolescents in the United Kingdom. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Heeringen, K.V. Suicide. Lancet 2009, 373, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.M. Adolescent depression and educational attainment: Results using sibling fixed effects. Health Econ. 2010, 19, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, S.; Ratelle, C.F.; Roy, A. Worries about middle school transition and subsequent adjustment. J. Early Adolesc. 2012, 32, 681–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Tang, S.; Ren, Z.; Wong, D.F.K. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among adolescents in secondary school in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Liu, G. Depression in Chinese adolescents from 1989 to 2018: An increasing trend and its relationship with social environments. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.; Eckenrode, J. Childhood psychological maltreatment subtypes and adolescent depressive symptoms. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 47, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.; Lee, Y. Developmental trajectories and longitudinal mediation effects of self-esteem, peer attachment, child maltreatment and depression on early adolescents. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 76, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yu, H. Relationship between children psychological maltreatment and depression among college students: A mediating effect of mental resilience. China J. Health Psychol. 2020, 28, 462–465. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, M.; Cho, S.; Yoon, D. Child maltreatment and depressive symptomatology among adolescents in out-of-home care: The mediating role of self-esteem. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 101, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Li, D.; Whipple, S.S. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 1342–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brassard, M.R.; Hart, S.N.; Hardy, D.B. Psychological and Emotional Abuse of Children. In Cas Studies in Family Violence; Ammerman, R.T., Hersen, M., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2000; pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L. Mediating effect of neuroticism and negative coping style in relation to childhood psychological maltreatment and smartphone addiction among college students in China. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 106, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brassard, M.R.; Hart, S.N.; Glaser, D. Psychological maltreatment: An international challenge to children’s safety and well being. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 52, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, G. Psychological maltreatment, coping strategies, and mental health problems: A brief and effective measure of psychological maltreatment in adolescents. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 68, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Liu, A. Childhood psychological maltreatment to depression: Mediating roles of automatic thoughts. J. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 36, 855–859. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Q.; Liu, A.; Li, S. The relationship between childhood psychological maltreatment and trait depression: A chain mediating effect of rumination and post-traumatic cognitive changes. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 23, 665–669. [Google Scholar]

- Edmiston, E.E. Corticostriatal-limbic gray matter morphology in adolescents with self-reported exposure to childhood maltreatment. Arch. Pediatrics Adolesc. Med. 2011, 165, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.Q.; Cui, Y.T. Recent research on the brain structure and functional changes in depression. China J. Health Psychol. 2007, 15, 468–470. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K. Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, S.R.; Ayduk, O.; Downey, G. The role of rejection sensitivity in people’s relationships with significant others and valued social groups. Interpers. Rejection 2001, 10, 251–289. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, G.; Freitas, A.L.; Michaelis, B.; Khouri, H. The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: Rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev-Wiesel, R.; Sternberg, R. Victimized at home revictimized by peers: Domestic child abuse a risk factor for social rejection. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2012, 29, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Dong, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhang, D. The relationship between parent phubbing and aggression among adolescents: The role of ostracism and interpersonal sensitivity. Psychol. Tech. Appl. 2020, 8, 513–520. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T.; Chen, Z. Meaning in life accounts for the association between long-term ostracism and depressive symptoms: The moderating role of self-compassion. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 160, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zalk, N.; Smith, R. Internalizing profiles of homeless adults: Investigating links between perceived ostracism and need-threat. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nolan, S.A.; Flynn, C.; Garber, J. Prospective relations between rejection and depression in young adolescents. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penhaligon, N.L.; Louis, W.R.; Restubog, S.L.D. Emotional anguish at work:The mediating role of perceived rejection on workgroup mistreatment and affective outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Penhaligon, N.L.; Louis, W.R.; Restubog, S.L.D. Feeling left out? The mediating role of perceived rejection on workgroup mistreatment and affective, behavioral, and organizational outcomes and the moderating role of organizational norms. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 480–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E. Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, T.A. Core self-evaluations and work success. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, W.B., Jr. Seeking “truth,” finding despair: Some unhappy consequences of a negative self-concept. Curr. Dir. Personal. Psychol. 1992, 1, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, C.; Barrowclough, C.; Calam, R. Parental criticism and adolescent depression: Does adolescent self-evaluation act as a mediator? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2009, 37, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, K.; Wang, Y.; Bin, J.; Liu, Y. Core self-evaluation, regulatory emotional self-efficacy, and depressive symptoms: Testing two mediation models. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2016, 44, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, B.; Zhang, X.; Wen, F.; Zhao, Y. The influence of stressful life events on depression among Chinese university students: Multiple mediating roles of fatalism and core self-evaluations. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, E.J.M. Separation: Anxiety and Anger: Attachment and Loss Volume 2; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wearden, A.; Peters, I.; Berry, K.; Barrowclough, C.; Liversidge, T. Adult attachment, parenting experiences, and core beliefs about self and others. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008, 44, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allbaugh, L.J.; Mack, S.A.; Culmone, H.D.; Hosey, A.M.; Dunn, S.E.; Kaslow, N.J. Relational factors critical in the link between childhood emotional abuse and suicidal ideation. Psychol. Serv. 2018, 15, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, M.D. A social-cognitive perspective on identity construction. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Liu, Q.Q.; Shen, X. Parental conflict and social networking sites addiction in Chinese adolescents: The multiple mediating role of core self-evaluation and loneliness. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, H.E.; Naser, J.; Al-Zaabi, A.; Al-Saeedi, A.; Al-Munefi, K.; Al-Houli, S.; Al-Rashidi, D. Childhood maltreatment: A predictor of mental health problems among adolescents and young adults. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 80, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakanyamale, A.A.; Yizhen, Y. Psychological maltreatment and its relationship with self-esteem and psychological stress among adolescents in Tanzania: A community based, cross-sectional study. Bmc Psychiatry 2019, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, K.D. Ostracism: A temporal need-threat model. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 41, 275–314. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Geng, J.; Zeng, P.; Gu, X.; Lei, L. Does peer alienation accelerate cyber deviant behaviors of adolescents? The mediating role of core self-evaluation and the moderating role of parent-child relationship and gender. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Dou, G.; Xie, L. Association between ostracism and self-esteem: The mediating effect of coping styles and the moderating effect of implicit theories of personality. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 28, 576–580. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, Y. The effect of campus exclusion on internalizing and externalizing problems: Mediating role of peer relationship and core self-evaluation. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2020, 36, 594–604. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.; Deng, Y.L.; Guan, B.Q.; Luo, X.R. Reliability and validity of child psychological maltreatment scale. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 18, 463–465. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, R.; Carter-Sowell, A.; Dewall, C.N.; Adams, R.E.; Carboni, I. Validation of the ostracism experience scale for adolescents. Psychol. Assess. 2013, 25, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, D. Dark triad and adolescents’ interpersonal trust: The mediating role of ostracism. Psychol. Tech. Appl. 2020, 8, 200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E.; Thoresen, C.J. The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Song, F.; Chen, Q.; Li, M.; Kong, F. Linking shyness to loneliness in Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of core self-evaluation and social support. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 125, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.M.; Malmgren, J.A.; Carter, W.B.; Patrick, D.L. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am. J. Prev. Med. 1994, 10, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Z. Child maltreatment in Western China: Demographic differences and associations with mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Strathearn, L.; Giannotti, M.; Mills, R.; Kisely, S.; Najman, J.; Abajobir, A. Long-term cognitive, psychological, and health outcomes associated with child abuse and neglect. Pediatrics 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, K.L.; LeMoult, J.; Wear, J.G.; Piersiak, H.A.; Lee, A.; Gotlib, I.H. Child maltreatment and depression: A meta-analysis of studies using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 102, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.J.L.; Brassard, M. Predictors of variation in sate reported rates of psychological maltreatment: A survey of statutes and a call for change. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 96, 104102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, B.; Downey, G.; Bonica, C.; Paltin, I. Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. J. Res. Adolesc. 2007, 17, 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.N.; Binggeli, N.J.; Brassard, M.R. Evidence for the effects of psychological maltreatment. J. Emot. Abus. 1997, 1, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, E.J.; Shochet, I.M.; Cockshaw, W.D.; Kelly, R.L. General belonging is a key predictor of adolescent depressive symptoms and partially mediates school belonging. Sch. Ment. Health 2020, 12, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, P.; Romero Lauro, L.J.; DeWall, C.N.; Bushman, B.J. Buffer the pain away: Stimulating the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex reduces pain following social exclusion. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 1473–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnelley, K.B.; Rowe, A.C. Repeated priming of attachment security influences later views of self and relationships. Pers. Relatsh. 2007, 14, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, A.A.; Messman-Moore, T.L. A structural model of mechanisms predicting depressive symptoms in women following childhood psychological maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowislo, J.F.; Orth, U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Nie, Y. Reflection and prospect on core self-evaluations. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 18, 1848–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Liu, A. The effect of childhood psychological maltreatment on depression: The mediation of cognitive flexibility. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2017, 201, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | 0.49 | 0.50 | 1 | |||||

| 2 Age | 13.23 | 0.96 | −0.03 | 1 | ||||

| 3 Psychological maltreatment | 1.67 | 0.55 | −0.06 * | 0.07 ** | 1 | |||

| 4 Perceived ostracism | 2.54 | 0.69 | −0.01 | 0.12 *** | 0.28 *** | 1 | ||

| 5 Core self-evaluation | 3.61 | 0.69 | −0.06 * | −0.13 *** | −0.44 *** | −0.48 *** | 1 | |

| 6 Depression | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.09 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.47 *** | −0.69 *** | 1 |

| Regression Model Outcome Variable | Predictor Variable | Goodness-of-Fit Indices | Regression Coefficient and Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | R2 | F | β | T | ||

| Perceived ostracism | 0.29 | 0.09 | 50.24 *** | |||

| Gender | 0.03 | 0.55 | ||||

| Age | 0.10 | 4.05 *** | ||||

| Psychological maltreatment | 0.27 | 11.29 *** | ||||

| Core self-evaluation | 0.59 | 0.34 | 207.65 *** | |||

| Gender | −0.18 | −4.33 *** | ||||

| Age | −0.07 | −3.29 ** | ||||

| Psychological maltreatment | −0.33 | −15.77 *** | ||||

| Perceived ostracism | − 0.38 | −17.83 *** | ||||

| Depression | 0.74 | 0.55 | 387.17 *** | |||

| Gender | 0.15 | 4.33 *** | ||||

| Age | 0.04 | 2.34 * | ||||

| Psychological maltreatment | 0.24 | 12.59 *** | ||||

| Perceived ostracism | 0.15 | 7.96 *** | ||||

| Core self-evaluation | −0.50 | −24.16 *** | ||||

| Effect | Effect Size | SE | Percentage of Total Effects | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Total effects | 0.500 | 0.021 | 100% | 0.458 | 0.542 |

| Direct effects | 0.238 | 0.019 | 47.60% | 0.201 | 0.275 |

| Total mediation effects | 0.262 | 0.019 | 52.40% | 0.227 | 0.299 |

| Psychological maltreatment→perceived ostracism→depression | 0.042 | 0.007 | 8.40% | 0.028 | 0.057 |

| Psychological maltreatment→core self-evaluation→depression | 0.168 | 0.014 | 33.60% | 0.142 | 0.197 |

| Psychological maltreatment→perceived ostracism→core self-evaluation→depression | 0.052 | 0.007 | 10.40% | 0.040 | 0.065 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Tu, R.; Hu, W.; Luo, X.; Zhao, F. Childhood Psychological Maltreatment and Depression among Chinese Adolescents: Multiple Mediating Roles of Perceived Ostracism and Core Self-Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111283

Wang Q, Tu R, Hu W, Luo X, Zhao F. Childhood Psychological Maltreatment and Depression among Chinese Adolescents: Multiple Mediating Roles of Perceived Ostracism and Core Self-Evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111283

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qiong, Ruilin Tu, Wei Hu, Xiao Luo, and Fengqing Zhao. 2021. "Childhood Psychological Maltreatment and Depression among Chinese Adolescents: Multiple Mediating Roles of Perceived Ostracism and Core Self-Evaluation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111283

APA StyleWang, Q., Tu, R., Hu, W., Luo, X., & Zhao, F. (2021). Childhood Psychological Maltreatment and Depression among Chinese Adolescents: Multiple Mediating Roles of Perceived Ostracism and Core Self-Evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111283