Views of Own Body Weight and the Perceived Risks of Developing Obesity and NCDs in South African Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Introduction and Socio-Demographics

3.2. Perceived Bodyweight

3.3. Perceived Risk of Developing NCDs

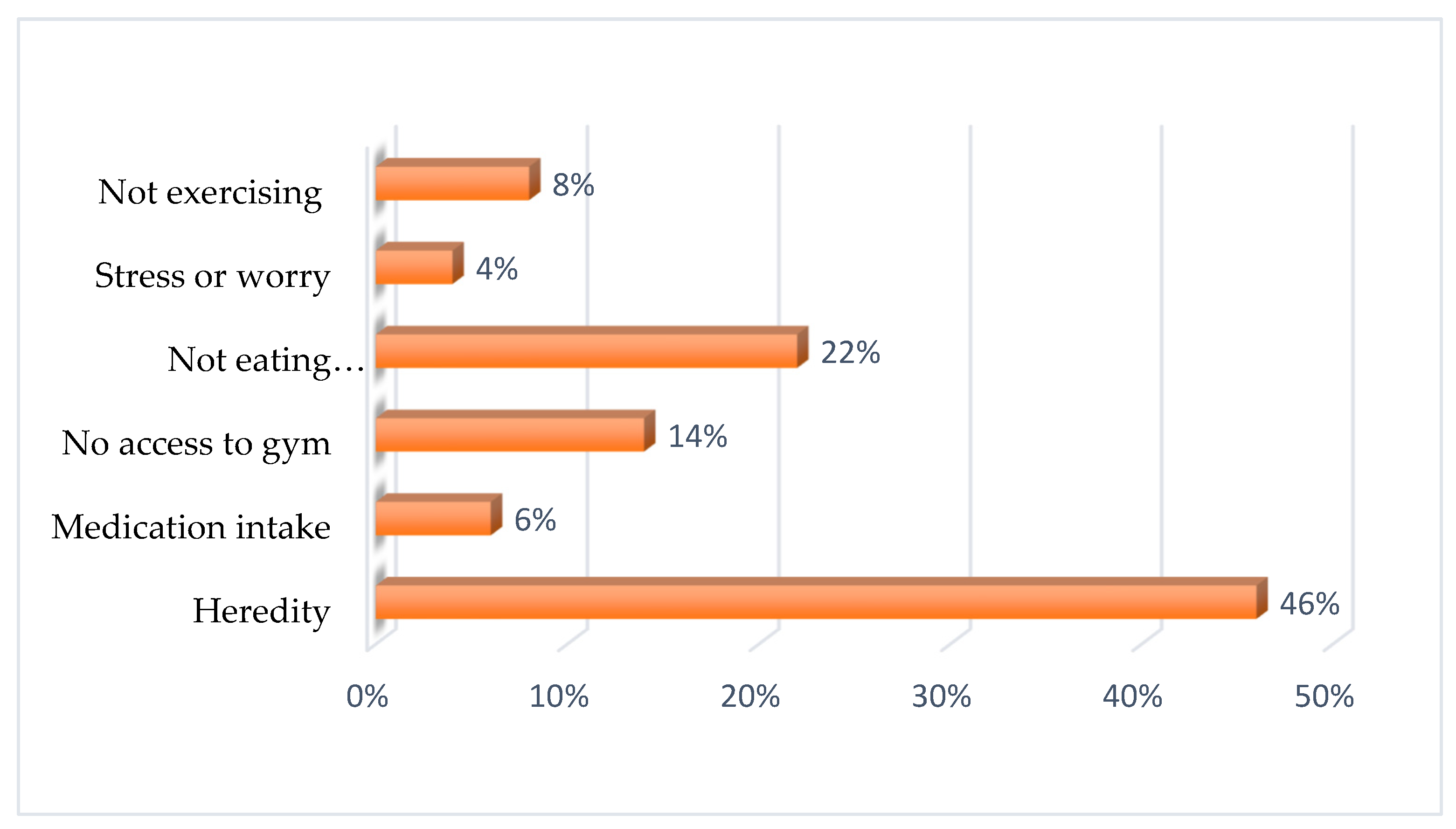

3.4. Perceived Factors Influencing Body Weight

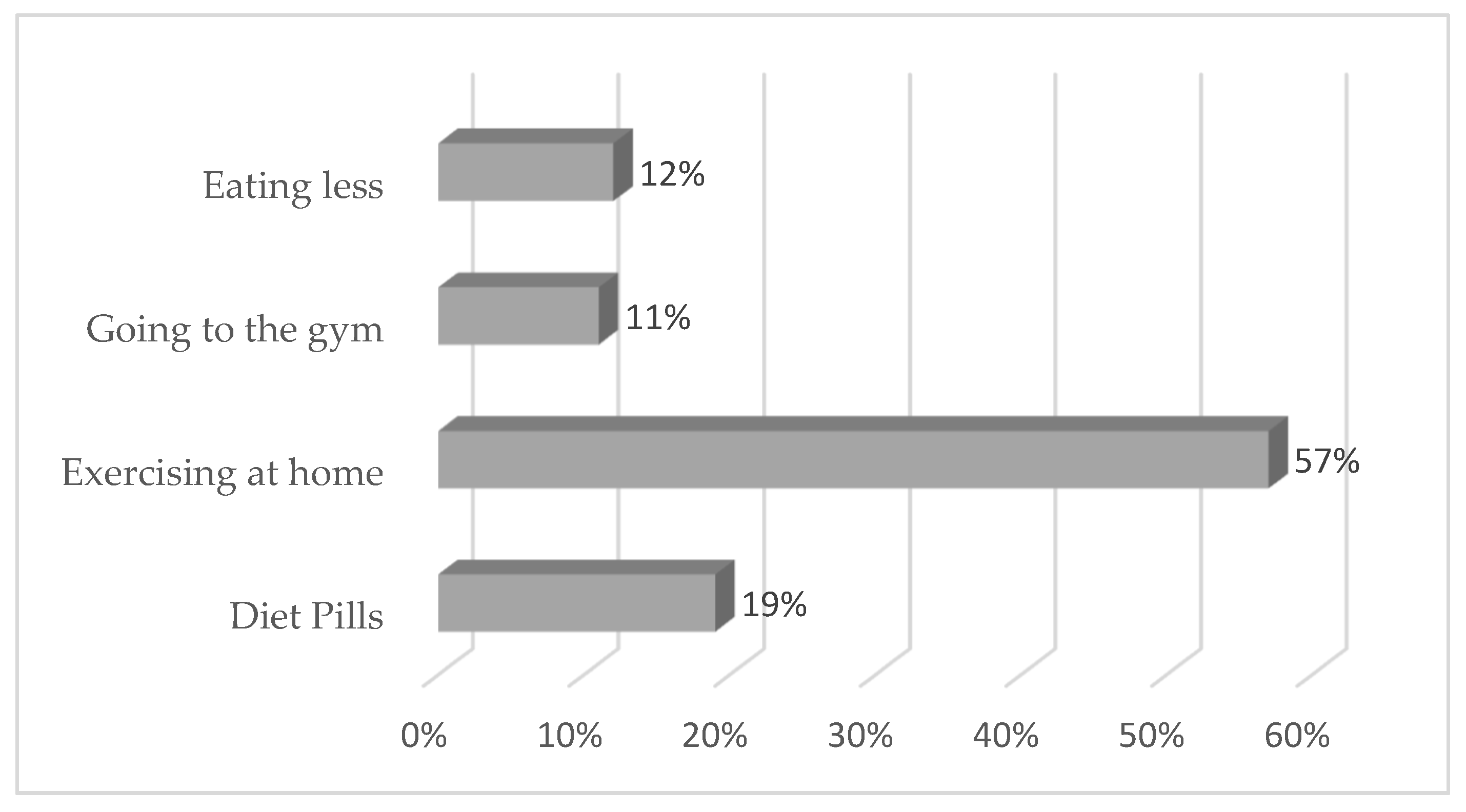

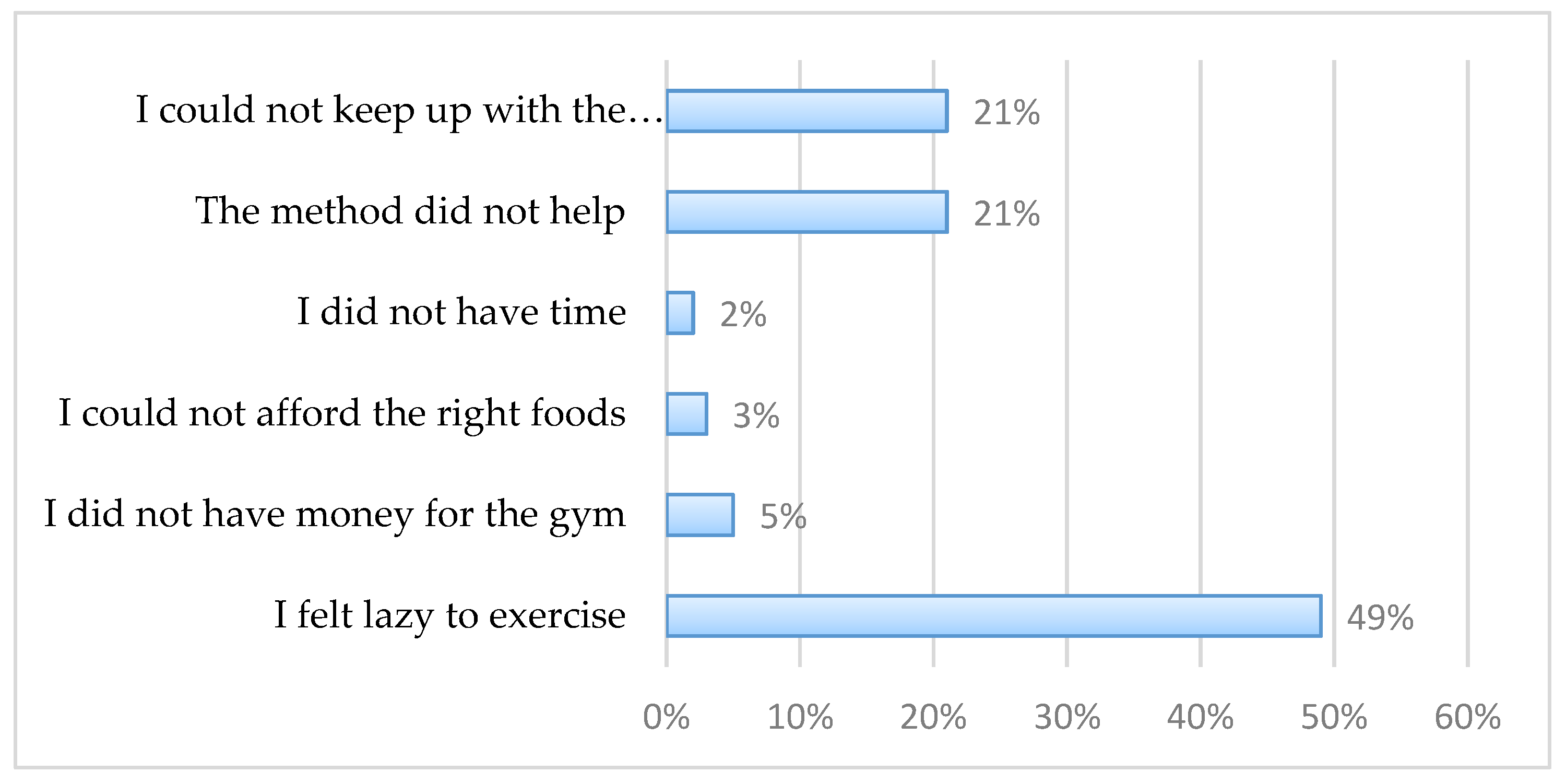

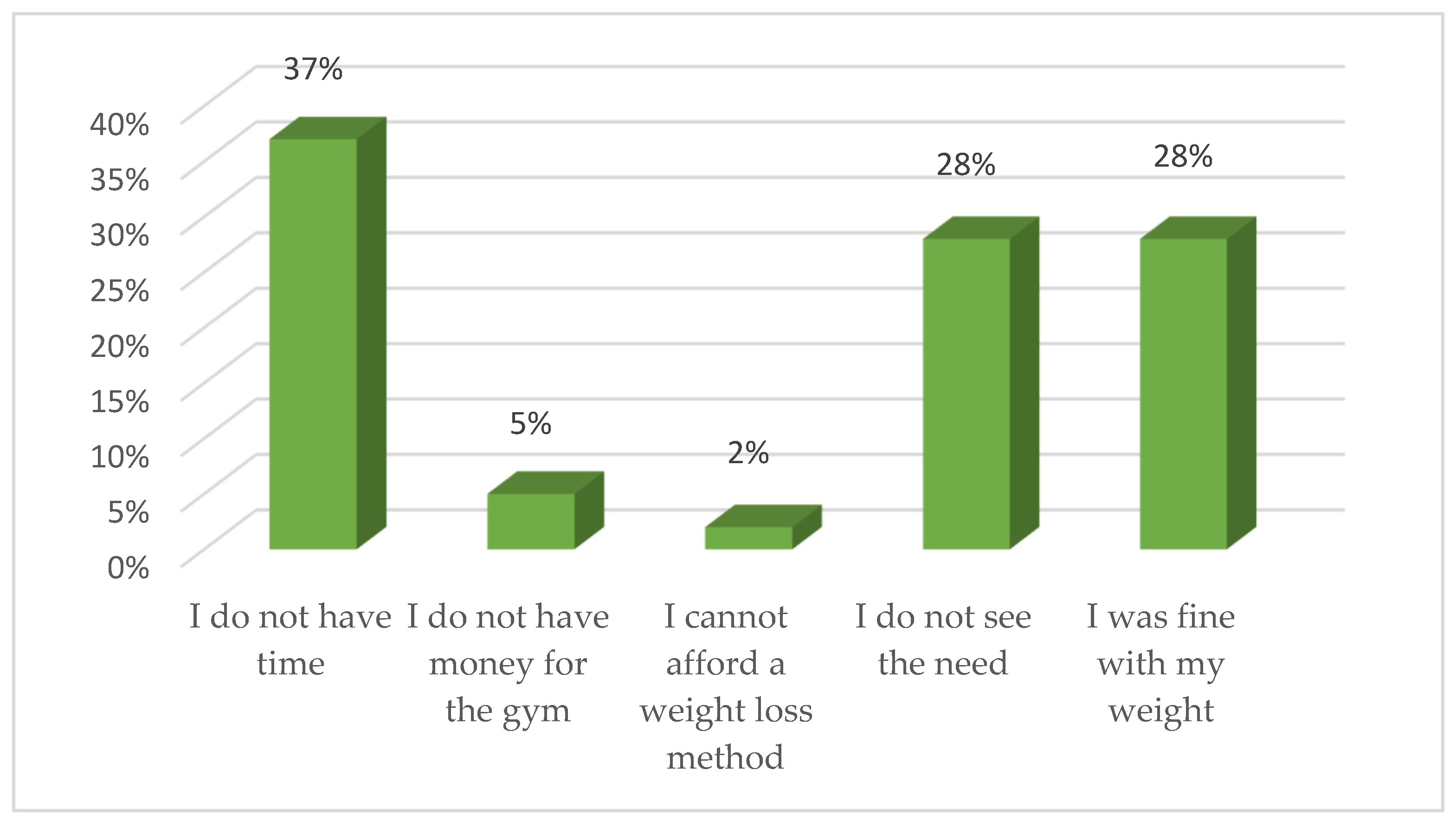

3.5. Self-Reported Weight Management Practices

3.6. Association between Misperception of Body Weight and Variables

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Non-Communicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- World Health Organization. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults, BMI ≥ 30, Age-Standardized Estimates by Country. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.CTRY2450A?lang=en (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- World Health Organization. Non-Communicable Diseases Country Profiles 2018: Factsheet South Africa. Available online: https://www.who.int/nmh/countries/zaf_en.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2018).

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 8 July 2018).

- Boyland, E.J.; Whalen, R. Food advertising to children and its effects on diet: Review of recent prevalence and impact data. Pediatric Diabetes 2015, 16, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinkohl, I.; Lachmann, G.; Brockhaus, W.-R.; Borchers, F.; Piper, S.K.; Ottens, T.H.; Nathoe, H.M.; Sauer, A.-M.; Dieleman, J.M.; Radtke, F.M. Association of obesity, diabetes and hypertension with cognitive impairment in older age. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 10, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, B.; Veerman, L.J.; Manyema, M.; Chola, L.; Hofman, K. Determinants of obesity and associated population attributability, South Africa: Empirical evidence from a national panel survey, 2008–2012. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130218. [Google Scholar]

- Okop, K.J.; Mukumbang, F.C.; Mathole, T.; Levitt, N.; Puoane, T. Perceptions of body size, obesity threat and the willingness to lose weight among black South African adults: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.M.; Dijkstra, S.; Visser, M. Self-perception of body weight status in older Dutch adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2015, 19, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaylis, J.B.; Levy, S.S.; Hong, M.Y. Relationships between body weight perception, body mass index, physical activity, and food choices in Southern California male and female adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E. Overweight but unseen: A review of the underestimation of weight status and a visual normalization theory. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 1200–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneville, K.; Thurston, I.; Milliren, C.; Kamody, R.; Gooding, H.; Richmond, T. Helpful or harmful? Prospective association between weight misperception and weight gain among overweight and obese adolescents and young adults. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muda, W.A.M.W.; Kuate, D.; Jalil, R.A.; Nik, W.S.W.; Awang, S.A. Self-perception and quality of life among overweight and obese rural housewives in Kelantan, Malaysia. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Aryeetey, R.N.O. Perceptions and experiences of overweight among women in the Ga East District, Ghana. Front. Nutr. 2016, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Hunger, J.; Daly, M. Perceived weight status and risk of weight gain across life in US and UK adults. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 1721–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Dunford, J.; Mehran, R.; Robson, S.; Kunadian, V. Pre-eclampsia and future cardiovascular risk among women: A review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akindele, M.O.; Phillips, J.S.; Igumbor, E.U. The relationship between body fat percentage and body mass index in overweight and obese individuals in an urban African setting. J. Public Health Afr. 2016, 7, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leedy, P.D.; Ormrod, J.E.; Johnson, L.R. Practical Research: Planning and Design; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Osail, A.M.; Al-Sheikh, M.H.; Al-Osail, E.M.; Al-Ghamdi, M.A.; Al-Hawas, A.M.; Al-Bahussain, A.S.; Al-Dajani, A.A. Is Cronbach′s alpha sufficient for assessing the reliability of the OSCE for an internal medicine course? BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Body Mass Index—BMI. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Bosire, E.N.; Cohen, E.; Erzse, A.; Goldstein, S.J.; Hofman, K.J.; Norris, S.A. ‘I’d say I’m fat, I’m not obese’: Obesity normalisation in urban-poor South Africa. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1515–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, B.E.; West, J.H.; Crookston, B.T.; Hall, P.C. Perceptions of Body Mass Index as a Valid Indicator of Weight Status among Adults in the United States. Health 2019, 11, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Smith, L.; Steptoe, A. Weight perceptions in older adults: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.A.; Lv, N.; Xiao, L.; Ma, J. Gender differences in weight-related attitudes and behaviors among overweight and obese adults in the United States. Am. J. Men′s Health 2016, 10, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorosty, A.R.; Mehdikhani, S.; Sotoudeh, G.; Rahimi, A.; Koohdani, F.; Tehrani, P. Perception of weight and health status among women working at Health Centres of Tehran. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2014, 32, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Gouda, H.N.; Charlson, F.; Sorsdahl, K.; Ahmadzada, S.; Ferrari, A.J.; Erskine, H.; Leung, J.; Santamauro, D.; Lund, C.; Aminde, L.N. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e1375–e1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, A.; Kersbergen, I.; Sutin, A.; Daly, M.; Robinson, E. A systematic review of the relationship between weight status perceptions and weight loss attempts, strategies, behaviours and outcomes. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzgar, C.; Preston, A.; Miller, D.; Nickols-Richardson, S. Facilitators and barriers to weight loss and weight loss maintenance: A qualitative exploration. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 28, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaoye, O.R.; Oyetunde, O.O. Perception of weight and weight management practices among students of a tertiary institution in south west Nigeria. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 2, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Heymsfield, S.B.; Wadden, T.A. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minos, D.; Butzlaff, I.; Demmler, K.M.; Rischke, R. Economic growth, climate change, and obesity. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2016, 5, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojilana, B.; Bradshaw, D.; Pillay-van Wyk, V.; Msemburi, W.; Somdyala, N.; Joubert, J.D.; Groenewald, P.; Laubscher, R.; Dorrington, R.E. Persistent burden from non-communicable diseases in South Africa needs strong action. S. Afr. Med J. 2016, 106, 436–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.; Subramanian, R.; Hinnant, A. Stigmatizing images in obesity health campaign messages and healthy behavioral intentions. Health Educ. Behav. 2016, 43, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sand, A.-S.; Emaus, N.; Lian, O.S. Motivation and obstacles for weight management among young women—A qualitative study with a public health focus—The Tromsø study: Fit Futures. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–35 years | 711 | 67 |

| 36–55 years | 280 | 27 |

| Older than 55 years | 58 | 6 |

| Sex | ||

| Females | 586 | 56 |

| Males | 463 | 44 |

| Marital status | ||

| Ever married | 311 | 30 |

| Single | 713 | 70 |

| Educational level | ||

| No formal education | 11 | 1 |

| Primary education | 48 | 4 |

| Secondary education | 268 | 26 |

| Tertiary education | 258 | 25 |

| Employment status | ||

| Not employed | 494 | 47 |

| Employed | 547 | 53 |

| Area of residence | ||

| Urban | 668 | 64 |

| Rural | 373 | 36 |

| BMI classification | ||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 64 | 6 |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 424 | 40 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 290 | 28 |

| Obese (30.0 kg/m2 and above) | 272 | 26 |

| Perceived Weight Status | Correctly Perceived Weight | Misperceived Weight | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100.0 | 5 |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 2 | 1.2 | 159 | 98.8 | 161 |

| Overweight and obese (25.0–above 40 kg/m2) | 0 | 0.0 | 381 | 100.0 | 381 |

| Perception of Risk of Developing NCDs | Not Overweight | Overweight | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| High blood pressure | ||||

| No | 19 | 8 | 224 | 92 |

| Yes | 17 | 5 | 331 | 95 |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||

| No | 25 | 7 | 323 | 93 |

| Yes | 11 | 5 | 231 | 95 |

| High cholesterol | ||||

| No | 24 | 8 | 296 | 93 |

| Yes | 12 | 4 | 257 | 96 |

| CVD | ||||

| No | 21 | 7 | 260 | 93 |

| Yes | 15 | 5 | 295 | 95 |

| Variables | Misperception of Body Weight (Bivariate Analysis) | Misperception of Body Weight (Multivariate Analysis) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p Value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.09 | - | - | - |

| Gender | 0.88 | 0.61–1.25 | 0.48 | - | - | - |

| Body Mass Index | 0.93 | 0.90–0.97 | * 0.00 | 0.94 | 0.91–0.98 | * 0.00 |

| Education level | 1.17 | 0.97–1.41 | 0.08 | - | - | - |

| Employment status | 1.59 | 1.13–2.24 | * 0.00 | 1.61 | 1.12–2.31 | * 0.00 |

| Marital status | 1.18 | 0.84–1.67 | 0.32 | - | - | - |

| Area of residence | 0.98 | 0.68–1.39 | 0.92 | - | - | - |

| Weight management behaviour | 1.27 | 0.97–1.66 | 0.07 | - | - | - |

| Risk of developing high blood pressure | 0.54 | 0.38–0.76 | * 0.00 | - | - | - |

| Risk of developing diabetes mellitus | 0.45 | 0.32–0.64 | * 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.37–1.00 | * 0.05 |

| Risk of developing high cholesterol | 0.49 | 0.35–0.69 | * 0.00 | - | - | - |

| Risk of developing cardiovascular diseases | 0.51 | 0.36–0.72 | * 0.00 | - | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manafe, M.; Chelule, P.K.; Madiba, S. Views of Own Body Weight and the Perceived Risks of Developing Obesity and NCDs in South African Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111265

Manafe M, Chelule PK, Madiba S. Views of Own Body Weight and the Perceived Risks of Developing Obesity and NCDs in South African Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111265

Chicago/Turabian StyleManafe, Mashudu, Paul K. Chelule, and Sphiwe Madiba. 2021. "Views of Own Body Weight and the Perceived Risks of Developing Obesity and NCDs in South African Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111265

APA StyleManafe, M., Chelule, P. K., & Madiba, S. (2021). Views of Own Body Weight and the Perceived Risks of Developing Obesity and NCDs in South African Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111265