Mental Health in Prison: Integrating the Perspectives of Prison Staff

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Shift towards the Recognition of Mental Healthcare in Italian Penitentiary System

1.2. Prisoners’ Mental Health

1.3. Effects of Italian Prison Legislation on Prison Organisation and Mental Healthcare

1.4. Prison Staff’s Mental Health and Work-Related Stress

2. The Research

2.1. Aims of the Study

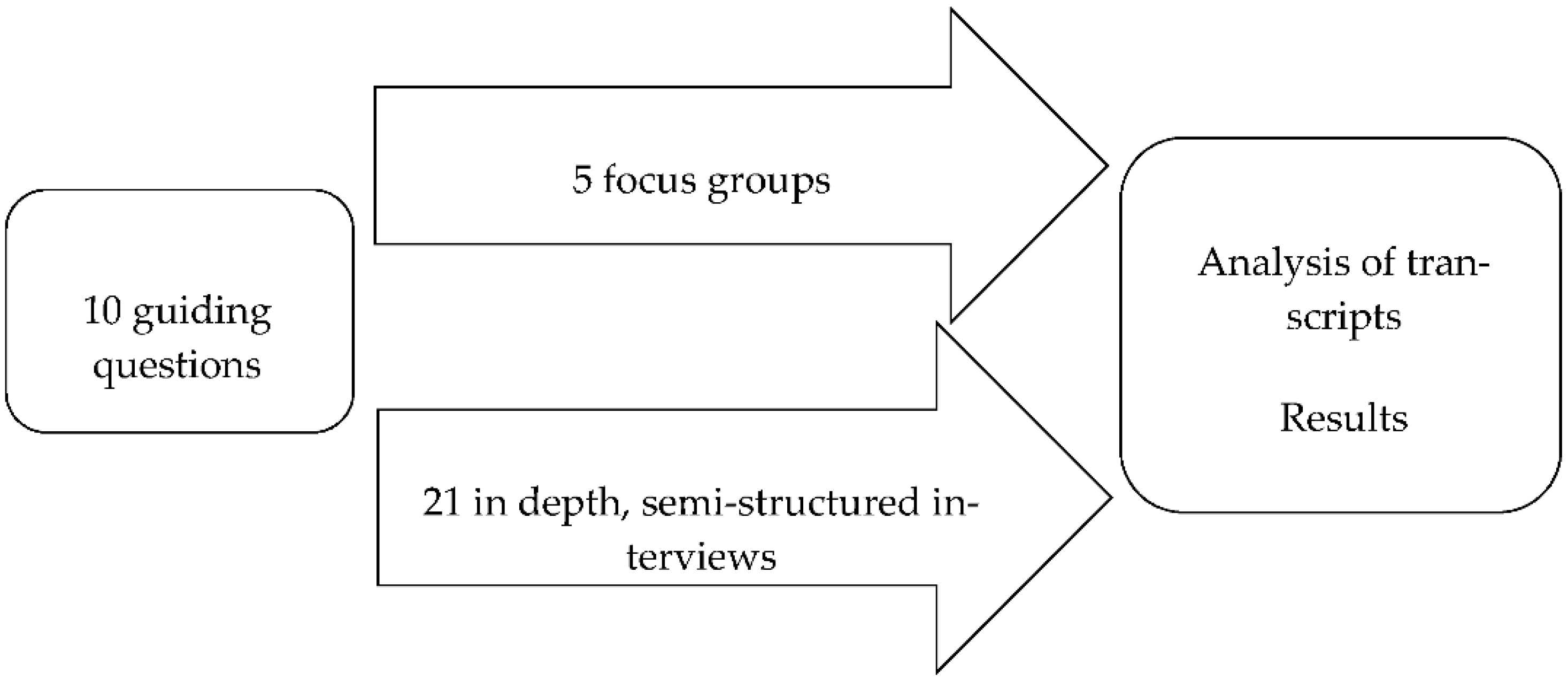

2.2. Methodology

2.3. Participants

2.4. Research Team

2.5. Thematic Analysis

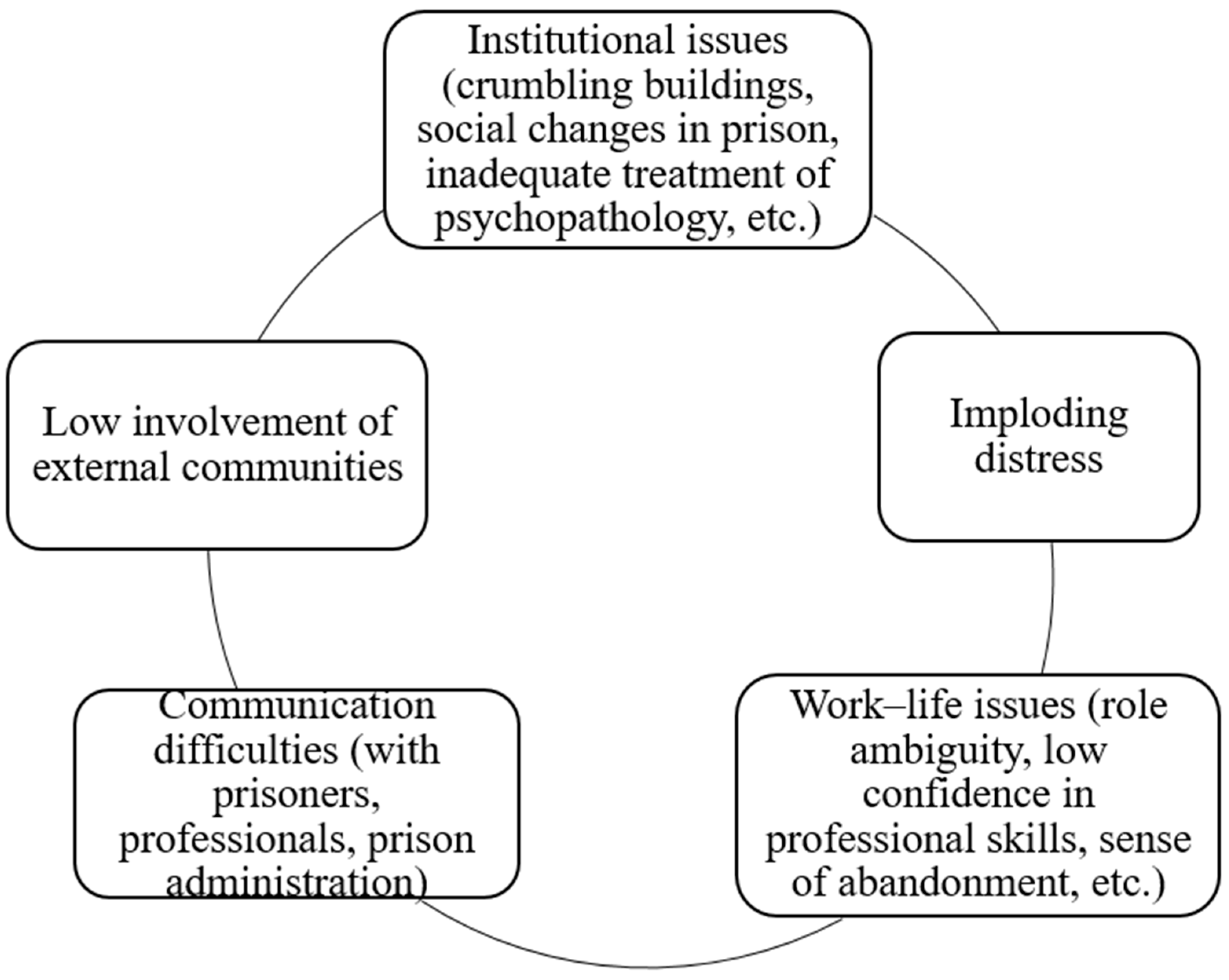

3. Results

We shouldn’t be subjected to the prisoners’ problems, it is not normal. […] I have adopted the technique of not listening to anyone. There are colleagues who listen to the prisoners’ problems; [the prisoners] throw their problems on them and the colleagues absorb them. But what kind of help can I give? I can only help until a certain point. I can’t provide psychological help; this is why I send them to talk to someone, even though there are very few trained staff members (1; 64).

The organisational system lacks the capacity [to address these problems]: we belong to three different areas, and, except for emergencies, there is no real dialogue, there is no designated team for prisoners with particular problems, there is no moment of confrontation; it occurs only from time to time (1; 69).

The outside community should intervene in order to prevent [recidivism], otherwise, the re-educational work we are doing inside of the prison will be in vain. […] in Italy, one or two of every 10 ex-offenders return to prison. If, once they find themselves outside of prison, they encounter a void or an absence of support, they [are likely to] return to committing crimes. It is then that we see if [re-education] is working, if the recidivism rate is decreasing. And it is not the prison’s fault, but the system’s (3; 100).

Listening is as important as knowing the person. When a person feels known, they have more confidence, and you are able to contain them. Observing and collaborating is crucial, and it arises from the goodwill of individuals, not from the institution (2; 20).

Another critical aspect in the management of patients is the conflict with prison administrators like PPOs [...]. They, […] would prefer that the patients be treated as they are in REMS, but we cannot provide this autonomy in their treatment because we are still inside of a prison. The 24-hour management [of patients] is their responsibility (12; 23).

4. Discussion

5. Limitation of the Study and Future Developments

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corte Costituzionale. Sentenza Nr. 99. 2019. Available online: https://www.cortecostituzionale.it/actionSchedaPronuncia.do?anno=2019&numero=99 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Senato Della Repubblica Costituzione Della Repubblica. 2009. Available online: http://www.senato.it/1025?sezione=121&articolo_numero_articolo=32 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. 1948. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Maroney, M.K. Caring and Custody: Two Faces of the Same Reality. J. Correct. Health Care 2005, 11, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lillo, M.; Associazione Antigone. Il Problema Della Salute Mentale in Carcere. 2019. Available online: https://antigoneonlus.medium.com/il-problema-della-salute-mentale-in-carcere-4ae94fe83391 (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Fazel, S.; Baillargeon, J. The health of prisoners. Lancet 2011, 377, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulten, E.; Vissers, A.; Oei, K. A Theoretical Framework for Goal-directed Care within the Prison System. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2008, 13, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Ramesh, T.; Hawton, K. Suicide in prisons: An international study of prevalence and contributory factors. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macciò, A.; Meloni, F.R.; Sisti, D.; Rocchi, M.; Petretto, D.R.; Masala, C.; Preti, A. Mental disorders in Italian prisoners: Results of the REDiMe study. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 225, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voller, F.; Silvestri, C.; Martino, G.; Fanti, E.; Bazzerla, G.; Ferrari, F.; Grignani, M.; Libianchi, S.; Pagano, A.M.; Scarpa, F.; et al. Health conditions of inmates in Italy. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aurizio, G.; Caldarola, A.; Ninniri, M.; Avvantaggiato, M.; Curcio, G. Sleep Quality and Psychological Status in a Group of Italian Prisoners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falissard, B.; Loze, J.-Y.; Gasquet, I.; Duburc, A.; De Beaurepaire, C.; Fagnani, F.; Rouillon, F. Prevalence of mental disorders in French prisons for men. BMC Psychiatry 2006, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piselli, M.; Attademo, L.; Garinella, R.; Rella, A.; Antinarelli, S.; Tamantini, A.; Quartesan, R.; Stracci, F.; Abram, K.M. Psychiatric needs of male prison inmates in Italy. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2015, 41, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavattini, G.C.; Garofalo, C.; Velotti, P.; Tommasi, M.; Romanelli, R.; Santo, H.E.; Costa, M.; Saggino, A. Dissociative Experiences and Psychopathology Among Inmates in Italian and Portuguese Prisons. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2015, 61, 975–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Grann, M.; Kling, B.; Hawton, K. Prison suicide in 12 countries: An ecological study of 861 suicides during 2003–2007. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 46, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelpietra, G.; Egidi, L.; Caneva, M.; Gambino, S.; Feresin, T.; Mariotto, A.; Balestrieri, M.; De Leo, D.; Marzano, L. Suicide and suicides attempts in Italian prison epidemiological findings from the “Triveneto” area, 2010–2016. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2018, 61, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, A.; Cascio, M.T. Prison Suicides and Self-harming Behaviours in Italy, 1990–2002. Med. Sci. Law 2006, 46, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Court of Human Rights. Second Section Case Torreggiani and Others vs. Italy (Cases no. 43517/09, 46882/09, 55400/09, 57875/09, 61535/09, 35315/10 and 37818/10). 2013. Available online: http://www.statewatch.org/news/2013/feb/italy.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Gatherer, A.; Möller, L.; Hayton, P. The World Health Organization European Health in Prisons Project After 10 Years: Persistent Barriers and Achievements. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 1696–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzetta Ufficiale. Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri 1 Aprile 2008. 2008. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2008/05/30/08A03777/sg (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Ferracuti, S.; Pucci, D.; Trobia, F.; Alessi, M.C.; Rapinesi, C.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Del Casale, A. Evolution of forensic psychiatry in Italy over the past 40 years (1978–2018). Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2018, 62, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boaron, F.; Gerocarni, B.; Fontanesi, M.G.; Zulli, V.; Fioritti, A. Across the walls. Treatment pathways of mentally ill offenders in Italy, from prisons to community care. J. Psychopathol. 2021, 27, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traverso, S.; Traverso, G.B. Revolutionary reform in psychiatric care in Italy: The abolition of forensic mental hospitals. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2017, 27, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boaron, F.; Fontanesi, M.; Marchesini, F.; Zulli, V.; Chiari, B.; Bartoletti, C. From trauma to offending—Some considerations about the impact of traumatic experiences on the clinical pathways of forensic psychiatric patients in secure residential settings. Ital. J. Criminol. 2019, 13, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associazione Antigone. XVI Rapporto 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.antigone.it/news/antigone-news/3301-il-carcere-al-tempo-del-coronavirus-xvi-rapporto-di-antigone-sulle-condizioni-di-detenzione (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Testoni, I.; Nencioni, I.; Ronconi, L.; Alemanno, F.; Zamperini, A. Burnout, Reasons for Living and Dehumanisation among Italian Penitentiary Police Officers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santorso, S. Rehabilitation and dynamic security in the Italian prison: Challenges in transforming prison officers’ roles. Br. J. Criminol. 2021, 61, 1557–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accordini, M.; Saita, E. The professional identity of juridical–educational professionals in prison. World Futures 2018, 74, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comitato Nazionale di Costruzione e Sviluppo del PDTA. Percorso Diagnostico Terapeutico Assistenziale (PDTA) Raccomandazioni per il paziente con disturbo mentale negli Istituti Penitenziari italiani. Riv. Psichiatr. 2017, 52, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioritti, A.; Melega, V. Italian forensic psychiatry: A story still to be written. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2000, 9, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Petrelli, F.; Cangelosi, G.; Scuri, S. Burnout syndrome: A preliminary study of a population of nurses in italian prisons. Clin. Ter. 2020, 171, e304–e309. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzari, T.; Terzoni, S.; Destrebecq, A.; Meani, L.; Bonetti, L.; Ferrara, P. Moral distress in correctional nurses: A national survey. Nurs. Ethics 2020, 27, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, L.; Bagnasco, A.; Bianchi, M.; Bressan, V.; Carnevale, F. Moral distress in undergraduate nursing students. Nurs. Ethics 2016, 23, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, F.; Delogu, B.; Bagnasco, A.; Sasso, L. Correctional nursing in Liguria, Italy: Examining the ethical challenges. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2018, 59, E315–E322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viotti, S. Work-related stress among correctional officers: A qualitative study. Work 2016, 53, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, T.J.; Wortley, R.K.; Stewart, A.L. Role conflict in community corrections. Psychol. Crime Law 2003, 9, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, B.; Hogan, N.L.; Kelley, T.; Kim, B.; Lambert, E.G. To Be or Not to Be Committed: The Effects of Continuance and Affective Commitment on Absenteeism and Turnover Intent among Private Prison Personnel. J. Appl. Secur. Res. 2013, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfood, V.W.; Pollock, W.; Longmire, D. Leave it at the gate: Job stress and satisfaction in correctional staff. Crim. Justice Stud. 2012, 26, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D. Focus group interviewing. In Handbook of Interview Research; Gubrium, J.F., Holstein, J.A., Eds.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, A.B.; Israel, B.A.; Parker, E.A.; Schulz, A.J. Review Of Community-Based Research: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, A.; Jewkes, R. What is a participatory research? Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, C.; Simpson, L.; Wood, L. Still left out in the cold: Problematising participatory research and development. Sociologia Rural. 2004, 44, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J. The methodology of Focus Groups: The importance of interaction between research participants. Sociol. Health Illn. 1994, 16, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning theory. In Contemporary Theories of Learning; Illeris, K., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addeo, F.; Montesperelli, P. Esperienze di Analisi di Interviste non Direttive; Aracne: Roma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amezcua, M.; Gálvez Toro, A. Los modos de análisis en investigación cualitativa en salud: Perspectiva crítica Y reflexiones en voz Alta. Rev. Española Salud Pública 2002, 76, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, I.; Meda, S.G. Metodi qualitativi E sociologia relazionale: Dimensioni culturali E riflessività nello studio Delle relazioni sociali. Sociol. Politiche Soc. 2017, 1, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhr, T. Atlas.ti Short User’s Guide; Scientific Software Development: Berlin, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Francioli, G.; Biancalani, G.; Libianchi, S.; Orkibi, H. Hardships in Italian Prisons During the COVID-19 Emergency: The Experience of Healthcare Personnel. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 619687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.L.; Hogan, N.L.; Lambert, E.G.; Tucker-Gail, K.A.; Baker, D.N. Job involvement, job stress, job satisfaction, and organisational commitment and the burnout of correctional staff. Crim. Justice Behav. 2010, 37, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutshall, C.L.; Hampton, D.P., Jr.; Sebetan, I.M.; Stein, P.C.; Broxtermann, T.J. The effects of occupational stress on cognitive performance in police officers. Police Pract. Res. 2017, 18, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maculan, A.; Vianello, F.; Ronconi, L. La polizia penitenziaria: Condizioni lavorative e salute organizzativa negli istituti penitenziari del Veneto. Ital. J. Criminol. 2016, 10, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Testoni, I.; Marrella, F.; Biancalani, G.; Cottone, P.; Alemanno, F.; Mamo, D.; Grassi, L. The Value of Dignity in Prison: A Qualitative Study with Life Convicts. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, C.; Stergiopoulos, E.; Hensel, J.; Bonato, S.; Dewa, C.S. Organisational stressors associated with job stress and burnout in correctional officers: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozza, D.; Trifiletti, E.; Vezzali, L.; Favara, I. Can intergroup contact improve humanity attributions? Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, N.; Stratemeyer, M. Recent research on dehumanisation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 11, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaes, J.; Muratore, M. Defensive dehumanisation in the medical practice: A cross-sectional study from a health care worker’s perspective. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 52, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealer, M.; Moss, M.; Good, V.; Gozal, D.; Kleinpell, R.; Sessler, C. What is burnout syndrome (BOS)? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 194, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.E. Burnout, coping and suicidal ideation: An application and extension of the job demand-control-support model. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2017, 32, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Testoni, I.; Nencioni, I.; Arbien, M.; Iacona, E.; Marrella, F.; Gorzegno, V.; Selmi, C.; Vianello, F.; Nava, A.; Zamperini, A.; et al. Mental Health in Prison: Integrating the Perspectives of Prison Staff. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111254

Testoni I, Nencioni I, Arbien M, Iacona E, Marrella F, Gorzegno V, Selmi C, Vianello F, Nava A, Zamperini A, et al. Mental Health in Prison: Integrating the Perspectives of Prison Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111254

Chicago/Turabian StyleTestoni, Ines, Irene Nencioni, Maibrit Arbien, Erika Iacona, Francesca Marrella, Vittoria Gorzegno, Cristina Selmi, Francesca Vianello, Alfonso Nava, Adriano Zamperini, and et al. 2021. "Mental Health in Prison: Integrating the Perspectives of Prison Staff" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111254

APA StyleTestoni, I., Nencioni, I., Arbien, M., Iacona, E., Marrella, F., Gorzegno, V., Selmi, C., Vianello, F., Nava, A., Zamperini, A., & Wieser, M. A. (2021). Mental Health in Prison: Integrating the Perspectives of Prison Staff. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111254