YouTube Doctors Confronting COVID-19: Scientific–Medical Dissemination on YouTube during the Outbreak of the Coronavirus Crisis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- −

- What kind of discursive strategies are using Spanish medical disseminators on COVID-19 on YouTube?

- −

- What key lines of action are they proposing to users facing the COVID-19 crisis?

- −

- What thematic and informative plots regarding the coronavirus can be identified in the production of Spanish medical disseminators focusing on COVID-19 on YouTube?

The Emergence of a New Way of Cultural and Scientific Dissemination

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Own a channel belonging to the Spanish context of YouTube and whose contents are developed in the Spanish language.

- (2)

- Own a channel for scientific–medical dissemination; this purpose was to be explicitly stated in the Home or More Information sections of the Channel. Accepted terminology: Disclosure/Communication/Information, on Medicine/Medical Science/Scientific-Medical/Biomedical/Biomedicine/Biomedical Engineering.

- (3)

- At least one year, in February 2020, since the publication of the first scientific-medical outreach video on their channel. The aim was to analyze medical disseminators with a solid track record on YouTube, avoiding creators who sprang up in the heat of the COVID-19 crisis without having previously published such work on the platform.

- (4)

- A minimum of 50,000 subscribers.

- (5)

- Careful video editing. The aim was to study content creators who carried out audio–visual dissemination with aesthetic and formal care, avoiding recordings of a single take without a minimal editing process.

- (6)

- Individual characters (personal, private, independent) and non-institutional (company, collective, association, research centres, universities). As researchers in media studies, we were interested in the application of the Youtuber phenomenon to academic, cultural, and scientific dissemination, and not as interested in the casuistry of institutions that decided to open a YouTube channel as a complement to their work in other areas.

- (7)

- Possess a higher degree (Bachelor’s degree or above) in Medicine or one of the following alternatives: Biomedicine, Biomedical Engineering.

Coding and Categorization

- −

- Expressive articulation: focused on the study of all those parameters linked to the enunciation of emotional, affective, or empathic elements by the disseminator, as well as their interweaving with the social reality generated by the COVID-19 crisis.

- −

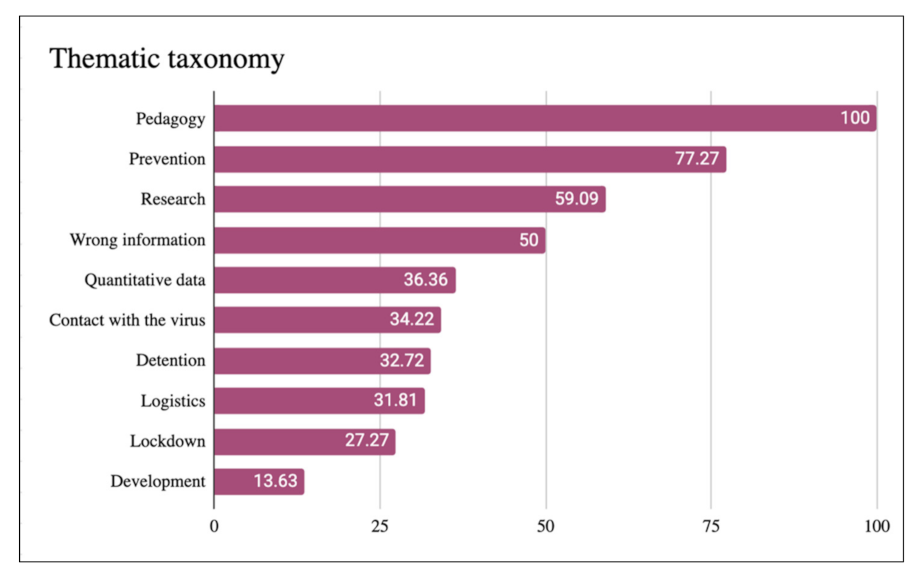

- Thematic taxonomy: focused on the study of all those matters concerning the COVID-19 health crisis and its classification into different thematic subcategories: pedagogy on the nature of the virus; symptomatology and treatment; prevention measures against COVID-19; global information and statistical data; experience as a health worker with direct treatments of the disease; etc.

- −

- Interaction with the audience: focused on the study of all those direct and explicit appeals by the disseminator towards the user/consumer of the videos, whether they were verbal or visual, or linked to the theme of COVID-19, and regardless of the aim of the interaction (an invitation to interact, encouragement to act, etc.).

3. Results

3.1. Expressive Articulation

3.2. Thematic Taxonomy

3.3. Interaction with the Audience

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| YouTube Channel | Video Name | Date | Visualizations | Comments | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glóbulo azul | MEDICO REAL EXPLICA EL CORONAVIRUS (COVID-19) Causas, Sintomas, Diagnostico, Tratamiento, Patologia https://bit.ly/3DeQTm7 | 2 March 2020 | 246,505 | 994 | 9:39 |

| Glóbulo azul | 3 médicos responden al ministerio https://bit.ly/3mw48YO | 7 March 2020 | 133,608 | 403 | 3:15 |

| Glóbulo azul | Médico responde a Paula Gonu sobre el Coronavirus https://bit.ly/2WLhveS | 13 March 2020 | 249,238 | 1067 | 25:21 |

| Glóbulo azul | ¿Por qué estamos en estado de alarma? ¿Cuánto de grave es la situación? https://bit.ly/3FmowUZ | 16 March 2020 | 120,426 | 517 | 7:42 |

| Glóbulo azul | ¿El Ibuprofeno empeora la enfermedad por Coronavirus? https://bit.ly/3FldeQS | 16 March 2020 | 112,577 | 442 | 7:22 |

| Glóbulo azul | ¿La cura contra el Coronavirus (COVID-19)? ¿Y la vacuna? https://bit.ly/2Ykym8M | 21 March 2020 | 62,087 | 250 | 8:13 |

| Glóbulo azul | ¿Cómo parar el Coronovarius/COVID-19? Esta es la estrategia https://bit.ly/3uNaffh | 25 March 2020 | 46,552 | 264 | 10:36 |

| Glóbulo azul | ¿Fin de la cuarentena? https://bit.ly/2YpiUrP | 10 April 2020 | 48,724 | 382 | 5:00 |

| Glóbulo azul | Salud mental en tiempos de COVID-19 https://bit.ly/2ZWhMNf | 26 April 2020 | 13,161 | 93 | 5:44 |

| Diario de un MIR | ¿Cómo puedo evitar infectarme de Coronavirus? https://bit.ly/3AaIY7q | 3 February 2020 | 73,884 | 463 | 18:04 |

| Diario de un MIR | Las nuevas medidas que se toman en mi hospital https://bit.ly/3oAbtJF | 25 February 2020 | 131,237 | 851 | 7:30 |

| Diario de un MIR | España: Aprended de lo que pasa en Italia, por favor https://bit.ly/3msmRo8 | 12 March 2020 | 61,059 | 610 | 2:29 |

| Diario de un MIR | Os pido mis sinceras disculpas https://bit.ly/3le0qDK | 13 March 2020 | 168,847 | 2.135 | 33:39 |

| Diario de un MIR | ¿Podéis confiar en Diario de un MIR? https://bit.ly/3uJFpUN | 20 March 2020 | 36,578 | 212 | 9:24 |

| Diario de un MIR | Mensaje de un médico de urgencias en Italia al presidente de México https://bit.ly/3AaJO44 | 24 March 2020 | 456,779 | 2968 | 5:23 |

| Diario de un MIR | 19 consejos para hacer un confinamiento de pacientes en casa https://bit.ly/3ad3SIy | 24 March 2020 | 29,030 | 167 | 6:14 |

| Diario de un MIR | ¿En qué consiste el test para el Coronavirus? https://bit.ly/2WKBYQX | 26 March 2020 | 24,615 | 147 | 10:15 |

| Diario de un MIR | ¡Nueva investigación importante! ¿Diagnóstico precoz de COVID-19? https://bit.ly/3FiBNxX | 5 April 2020 | 40,288 | 179 | 12:45 |

| Diario de un MIR | Si seguimos así vamos a tener una segunda oleada fuerte (espero equivocarme) https://bit.ly/3ixjviD | 10 April 2020 | 542,211 | 3521 | 7:30 |

| Diario de un MIR | ¡Que no te pase esto! Casi me desmayo en mi primera cirugía. https://bit.ly/3mqPRgc | 12 April 2020 | 32,817 | 182 | 11:00 |

| La Hiperactina | Coronavirus, ¿qué ha pasado? https://bit.ly/2YynX9Q | 6 March 2020 | 217,938 | 1057 | 13:14 |

| La Hiperactina | Actualización sobre el Coronavirus https://bit.ly/3DfRZ0P | 26 March 2020 | 153,010 | 1163 | 15:39 |

| Iván Moreno | Presentación y situación general COVID-19 https://bit.ly/3mtMFQP | 17 March 2020 | 8418 | 11 | 12:54 |

| Iván Moreno | Actualización Covid 18 marzo https://bit.ly/3a9KlbN | 18 March 2020 | 1556 | 0 | 10:01 |

| Iván Moreno | Actualización Covid del 20 de marzo https://bit.ly/3iC20gY | 20 March 2020 | 1791 | 5 | 15:19 |

| Iván Moreno | Actualización Covid del 22 de marzo https://bit.ly/3iBEGQA | 22 March 2020 | 1497 | 2 | 11:24 |

| Iván Moreno | Creo que tengo Coronavirus, ¿qué hago? https://bit.ly/3mqt0RT | 23 March 2020 | 11,259 | 6 | 12:11 |

| Iván Moreno | Actualización Covid del 24 de marzo https://bit.ly/302MaFV | 24 March 2020 | 2301 | 1 | 13:21 |

| Iván Moreno | Coronavirus, ¿cómo salimos de esta? (1 de 3) https://bit.ly/3msxAiz | 27 March 2020 | 18,044 | 9 | 12:09 |

| Iván Moreno | Coronavirus, ¿cómo salimos de esta? (2 de 3) https://bit.ly/3lerfrm | 27 March 2020 | 9156 | 0 | 13:48 |

| Iván Moreno | Coronavirus, ¿cómo salimos de esta? (3 de 3) https://bit.ly/2Ywk3OX | 27 March 2020 | 12,623 | 14 | 9:38 |

| Iván Moreno | Introducción nuevo formato RCP COVID-19 https://bit.ly/3AaQjnD | 14 April 2020 | 10,115 | 28 | 7:34 |

| Iván Moreno | De guardia https://bit.ly/3Bgf17l | 15 April 2020 | 895,420 | 390 | 9:34 |

| Iván Moreno | Sobre los test en Covid (1 de 2: tipos y usos) https://bit.ly/2ZW9rsV | 17 April 2020 | 100,578 | 77 | 13:59 |

| Iván Moreno | Sobre los test en Covid (2 de 2: interés individual y poblacional) https://bit.ly/3uK6fft | 17 April 2020 | 51,217 | 169 | 18:30 |

| Iván Moreno | Confianza ¿ciega? https://bit.ly/3iDNnd3 | 20 April 2020 | 44,916 | 171 | 17:39 |

| Iván Moreno | Antihipertensivos y COVID-19 https://bit.ly/3uMWQnf | 21 April 2020 | 35,023 | 45 | 5:43 |

| Iván Moreno | Lo que aporta una semana… https://bit.ly/3AgkbPe | 25 April 2020 | 931,429 | 732 | 19:30 |

| Iván Moreno | Especial preguntas y respuestas https://bit.ly/2WJBURs | 27 April 2020 | 97,124 | 369 | 1:51:06 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | El Coronavirus ya está aquí (COVID-19) https://bit.ly/3DhsufS | 29 February 2020 | 44,960 | 97 | 16:29 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | La verdad sobre el Coronavirus (reflexiones de un médico de familia) https://bit.ly/3uJSH3o | 7 March 2020 | 999,532 | 1770 | 24:59 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Coronavirus. Qué está pasando? (Reflexiones de un médico de familia) https://bit.ly/3BkAD2y | 14 March 2020 | 135,555 | 591 | 12:19 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Spiriman, Sálvame y el Coronavirus (médico de familia de Ibiza le responde) https://bit.ly/2YqLTeQ | 18 March 2020 | 1,080,576 | 2585 | 19:59 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Coronavirus: miserables y canallas (testimonios profesionales) https://bit.ly/3oGYeXx | 21 March 2020 | 1,271,797 | 2857 | 8:35 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Coronavirus: alarmismo, sanitarios contagiados, confinamiento y testimonios https://bit.ly/3uLK5cx | 23 March 2020 | 167,558 | 1317 | 22:29 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Coronavirus: políticos y Spiriman (donaciones) https://bit.ly/3oKtZii | 24 March 2020 | 107,278 | 1014 | 21:11 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Casos reales, atención primaria y cloroquina/hidroxicloroquina. https://bit.ly/3uNbPgQ | 28 March 2020 | 179,439 | 692 | 10:56 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Coronavius: lo bueno, lo feo y lo malo https://bit.ly/3ldjbY3 | 4 April 2020 | 105,354 | 561 | 28:13 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Test de Roth: dificultad respiratoria https://bit.ly/3lfTxSl | 5 April 2020 | 230,001 | 471 | 4:42 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Cómo protegerse del Coronavirus SARS Cov-2 https://bit.ly/3uTpP9a | 11 April 2020 | 112,733 | 512 | 19:05 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Desconfinamiento: ¿nuevo pico? https://bit.ly/3leBbBa | 15 April 2020 | 117,795 | 492 | 13:47 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | ¿Te pondrás la vacuna del Coronavirus cuando esté disponible? https://bit.ly/3AijmW6 | 21 April 2020 | 292,279 | 1231 | 4:03 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Desconfinamientos, brotes en otoño y ¿culpables de la pandemia? https://bit.ly/3oClTZ7 | 25 April 2020 | 74,972 | 575 | 22:42 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | ¡Me timaron! (Mascarillas y material sanitario) https://bit.ly/3uJm1qV | 26 April 2020 | 43,725 | 611 | 7:34 |

References

- D’Souza, R.S.; D’Souza, S.; Strand, N.; Anderson, A.; Vogt, M.N.P.; Olatoye, O. YouTube as a source of medical information on the novel coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igartua, J.-J.; Ortega-Mohedano, F.; Arcila-Calderón, C. Communication use in the times of the coronavirus. A cross-cultural study. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompare, D. Flow to files: Conceiving 21st century media. In Proceedings of the Media in Transition 2 Conference, Cambridge, MA, USA, 11 May 2002; Available online: http://cmsw.mit.edu/mit2/Abstracts/DerekKompare.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-García, I.; Giménez-Júlvez, T. Characteristics of YouTube Videos in Spanish on How to Prevent COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casetti, F. Teorie del Cinema (1945–1990); Bompiani: Milan, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Casetti, F.; Di Chio, F. Analisi del Film; Bompiani: Milan, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Odin, R. Semiotica e analisi testuale dei film. Bianco Nero 1988, 11, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Odin, R. Cinéma et Production du Sens; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Casetti, F.; Di Chio, F. Analisi della Televisione. Strumenti, Metodie Pratiche di Ricerca; Bompiani: Milan, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. (Ed.) ‘TV: La transparenza perduta’. In Sette Anni di Desiderio; Bompiani: Milan, Italy, 1985; pp. 308–322. [Google Scholar]

- Bordwell, D.; Thompson, K. Film Art: An Introduction; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, P. The Discourse of YouTube: Multimodal Text in a Global Context; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J. From ‘Broadcast yourself’ to ‘Follow your interests’: Making over social media. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2015, 18, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez, Á.E.; Jiménez, M.E.B.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Mafokozi, J. Análisis del tratamiento de contenidos en la creación de audiovisuales educativos (parte II): Las progresiones detectadas. Rev. Eureka Sobre Enseñanza Divulg. Cienc. 2019, 16, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cunningham, S.; Craig, D. Being ‘really real’ on YouTube: Authenticity, community and brand culture in social media entertainment. Media Int. Aust. 2017, 164, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S.; Craig, D.R. Social Media Entertainment: The New Intersection of Hollywood and Silicon Valley; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, B.E.; Hund, E. “Having it All” on Social Media: Entrepreneurial Femininity and Self-Branding Among Fashion Bloggers. Soc. Media Soc. 2015, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasena, J.M. Negotiating Collaborations: BookTubers, The Publishing Industry, and YouTube’s Ecosystem. Soc. Media Soc. 2019, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, B.; Bourk, M. Investigating science-related online video. In Communicating Science and Technology through Online Video; León, B., Bourk, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Welbourne, D.J.; Grant, W. Science communication on YouTube: Factors that affect channel and video popularity. Public Underst. Sci. 2016, 25, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieborg, D.B.; Poell, T. The platformization of cultural production: Theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 4275–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burgess, J.; Green, J. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture; Polity Press: Medford, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. The institutionalization of YouTube: From user-generated content to professionally generated content. Media Cult. Soc. 2012, 34, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijck, J. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berzosa, M.I. Youtubers y Otras Especies. El Fenómeno que ha Cambiado la Manera de Entender los Contenidos Audiovisuales; Fundación Telefónica: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, S.; Moura, P.; Fillol, J. El fenómeno de los YouTubers: ¿qué hace que las estrellas de YouTube sean tan populares entre los jóvenes? Fonseca J. Commun. 2018, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolari, C.A.; Fraticelli, D. The case of the top Spanish YouTubers: Emerging media subjects and discourse practices in the new media ecology. Converg. Int. J. Res. New Media Technol. 2017, 25, 496–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran-Ramspott, S.; Fedele, M.; Tarragó, A. YouTubers social functions and their influence on pre-adolescence. Comunicar 2018, 26, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, P.G. Kids on YouTube: Technical Identities and Digital Literacies; Routledge: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Torres, V.; Pastor-Ruiz, Y.; Abarrou-Ben-Boubaker, S. YouTuber videos and the construction of adolescent identity. Comunicar 2018, 26, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pires, F.; Masanet, M.-J.; Scolari, C.A. What are teens doing with YouTube? Practices, uses and metaphors of the most popular audio-visual platform. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2021, 24, 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westenberg, W. The Influence of Youtubers on Teenagers. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rovira-Collado, J. Booktrailer y Booktuber como herramientas LIJ 2.0 para el desarrollo del hábito lector. Investig. Sobre Lect. 2017, 7, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcaíno-Verdú, A.; Contreras-Pulido, P.; Guzmán-Franco, M.-D. Reading and informal learning trends on YouTube: The booktuber. Comunicar 2019, 27, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Martínez, Á.E.; Jiménez, E.B.; Mafokozi, J. Análisis del tratamiento de contenidos en la creación de audiovisuales educativos. Rev. Eureka Sobre Enseñanza Divulg. Cienc. 2018, 16, 1–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erviti, M.C.; Stengler, E. Online science videos: An exploratory study with major professional content providers in the United Kingdom. J. Sci. Commun. 2016, 15, A06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Francés, M.; Peris, À. Rigour in online science videos: An initial approach. In Communicating Science and Technology through Online Video; León, B., Bourk, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.; León, B. New and old narratives: Changing narratives of science documentary in the digital environment. In Communicating Science and Technology through Online Video; León, B., Bourk, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bourk, M.; León, B.; Davis, L. Entertainment in science: Useful in small doses. In Communicating Science and Technology through Online Video; León, B., Bourk, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- Erviti, M.C. Producing science online video. In Communicating Science and Technology through Online Video; León, B., Bourk, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, S. Managing visibility on YouTube through algorithmic gossip. New Media Soc. 2019, 21, 2589–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gran, A.-B.; Booth, P.; Bucher, T. To be or not to be algorithm aware: A question of a new digital divide? Inf. Commun. Soc. 2021, 24, 1779–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reviglio, U.; Agosti, C. Thinking outside the Black-Box: The Case for “Algorithmic Sovereignty” in Social Media. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120915613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Moreno, F. ‘Notice and staydown’ and social media: Amending Article 13 of the Proposed Directive on Copyright. Int. Rev. Law Comput. Technol. 2018, 33, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F.R. ‘Upload filters’ and human rights: Implementing Article 17 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market. Int. Rev. Law Comput. Technol. 2020, 34, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuboff, S. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, W.J.; Brown, A. Working with Qualitative Data; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, D. Social Psychology; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.; Seifert, C.; Schwarz, N.; Cook, J. Misinformation and its correction: Continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2012, 13, 106–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Channel | Creator | Degree | Number of Subscribers (March 2021) | COVID-19 Videos (2/3/4—2020) | Accumulated Views (March 2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glóbulo azul | Amyad Raduán | Medicine | 235,000 | 9 | 1,006,218 |

| Diario de un MIR | Pau Mateo | Medicine | 102,600 | 11 | 2,299,419 |

| La Hiperactina | Sandra Ortonobes | Biomedicine | 130,000 | 2 | 262,971 |

| Iván Moreno | Iván Moreno | Medicine | 78,800 | 17 | 2,208,951 |

| Alberto Sanagustín | Alberto Sanagustín | Medicine | 447,000 | 15 | 4,735,080 |

| 1. Informative/Didactic Tone | |

| 2. Emotional reaction | 2.1. Exclamation (including bad language) |

| 2.2. Emotionality | |

| 2.3. Despair/grief | |

| 2.4. Empathy | |

| 2.5. Annoyance | |

| 2.6. Fear | |

| 3. Criticism/complaint about: | 3.1. Institutional measures |

| 3.2. Citizen behaviour | |

| 3.3. Someone in particular | |

| 3.4. Self-criticism | |

| 4. Hilarious escape/laughter/affability | |

| 5. Irony/sarcasm | |

| 1. Pedagogy | 1.1. SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 |

| 1.2. Origin/History of coronaviruses | |

| 1.3. Virology/Bioscience in general | |

| 2. Detention | 2.1. Symptomatology |

| 2.2. Diagnosis/Test | |

| 3. Contact with the virus | 3.1. Infection |

| 3.2. Transmission | |

| 4. Development | 4.1. Treatment |

| 4.2. Pharmacology | |

| 5. Prevention | 5.1. Preventive tools |

| 5.2. Recommendations for action | |

| 6. Lockdown | 6.1. Tips for confinement–quarantine |

| 6.2. Psychological consequences | |

| 7. Wrong information | 7.1. Hoaxes |

| 7.2. Misinformation | |

| 7.3. Pseudoscience | |

| 8. Quantitative data | 8.1. Transnational data |

| 8.2. Statistical information/Ratios | |

| 9. Logistics | 9.1. Hospitals |

| 9.2. Healthcare system | |

| 9.3. Own experience as a professional | |

| 10. Research | 10.1. Vaccine |

| 10.2. Scientific evidence (studies, papers) | |

| 10.3. Authority quotes |

| 1. Non-thematic appeal | 1.1. Presentation |

| 1.2. Initial greeting | |

| 1.3. Farewell | |

| 1.4. Gratefulness | |

| 2. Message of encouragement/good wishes | |

| 3. Appeal to the population to | 3.1. Keep calm/keep tranquil/no hysteria |

| 3.2. Responsibility/non-trivialization | |

| 4. Presence of messages from the audience | 4.1. Verbally |

| 4.2. Visually | |

| 5. Link to other audiovisual resources | 5.1. Other videos from the same channel (past and future) |

| 5.2. Other networks of the disseminator | |

| 5.3. Other creators | |

| 6. Direct call to interact | 6.1. Like it |

| 6.2. Send comment | |

| 6.3. Share video | |

| 6.4. Channel subscription | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buitrago, Á.; Martín-García, A. YouTube Doctors Confronting COVID-19: Scientific–Medical Dissemination on YouTube during the Outbreak of the Coronavirus Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111229

Buitrago Á, Martín-García A. YouTube Doctors Confronting COVID-19: Scientific–Medical Dissemination on YouTube during the Outbreak of the Coronavirus Crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111229

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuitrago, Álex, and Alberto Martín-García. 2021. "YouTube Doctors Confronting COVID-19: Scientific–Medical Dissemination on YouTube during the Outbreak of the Coronavirus Crisis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111229

APA StyleBuitrago, Á., & Martín-García, A. (2021). YouTube Doctors Confronting COVID-19: Scientific–Medical Dissemination on YouTube during the Outbreak of the Coronavirus Crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111229