Use of the Washington Group Questions in Non-Government Programming

Abstract

:1. Introduction

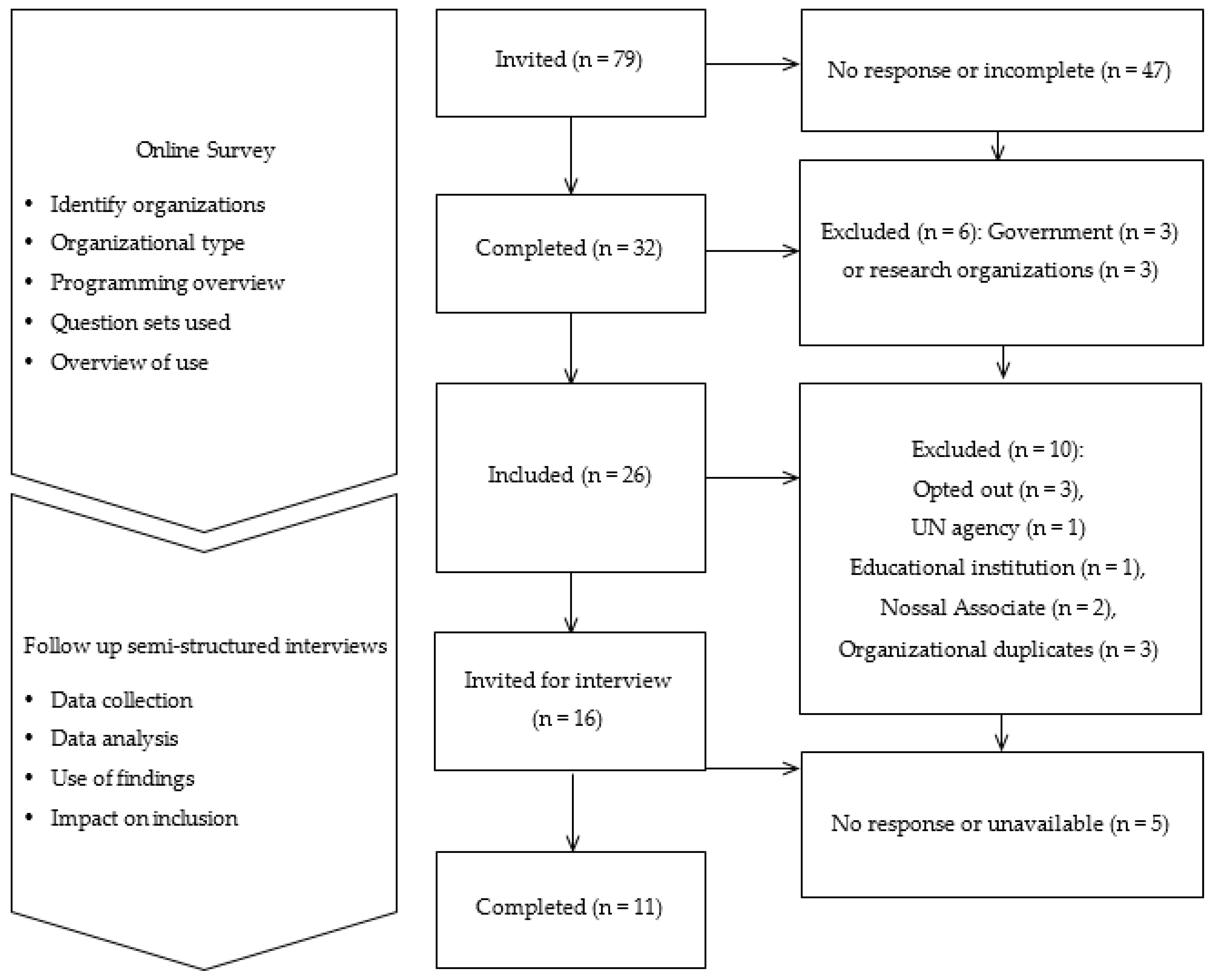

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Online Survey

3.2. Semi-Structured Interview Findings

3.2.1. Rationale for Using the Questions

3.2.2. Guidance and Disability Inclusion in Data Collection

3.2.3. Integration in Data Collection Tools and Modifications

3.2.4. Translations

3.2.5. Data Analysis and Cut off Points

3.2.6. Identification, Participation, and Screening

4. Discussion

4.1. Use of the Questions in NGO Programming

4.2. The Need for Realistic Expectations

4.3. Flexibility in Use

4.4. Processes Rather Than Outcomes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. About the WG. Available online: https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/about/about-the-wg/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Madans, J.H.; Loeb, M.E.; Altman, B.M. Measuring disability and monitoring the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: The work of the Washington Group on Disability Statistics. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robinson, A.; Kani, S. Disability-inclusive DRR: Information, Risk and Practical Action. In Civil Society Organization and Disaster Risk Reduction: The Asian Dilemma; Shaw, R., Izumi, T., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sightsavers. Everybody Counts: Disability Disaggregation of Data Pilot Projects in India and Tanzania: Final Evaluation Report; Sightsavers: Chippenham, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.sightsavers.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/everybodycounts_brochure_accessible_web.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Sloman, A.; Margaretha, M. The Washington Group Short Set of Questions on Disability in Disaster Risk Reduction and humanitarian action: Lessons from practice. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Statement by the Disability Sector: Disability Data Disaggregation. In Proceedings of the Fifth meeting of the IAEG-SDGs, Ottawa, Canada, 28–31 March 2017; Available online: http://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/data-joint-statement-march2017 (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Light for the World. Resource Book on Disability Inclusion. 2017. Available online: https://www.light-for-the-world.org/sites/lfdw_org/files/download_files/resource_book_disability_inclusion.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Age and Disability Consortium. Humanitarian Inclusion Standards for Older People and People with Disabilities; CBM International: Bleinham, Germany; HelpAge International: London, UK; Handicap International: Lyon, France, 2018; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Humanitarian_inclusion_standards_for_older_people_and_people_with_disabi....pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee. Guidelines on the Inclusion of People with Disability in Humanitarian Action. 2019. Available online: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2020-11/IASC%20Guidelines%20on%20the%20Inclusion%20of%20Persons%20with%20Disabilities%20in%20Humanitarian%20Action%2C%202019_0.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M. The difference a word makes: Responding to questions on ‘disability’ and ‘difficulty’ in South Africa. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. An Introduction to the Washington Group on Disability Statistics Question Sets. 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/fileadmin/uploads/wg/Documents/An_Introduction_to_the_WG_Questions_Sets__2_June_2020_.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Mactaggart, I.; Bek, A.H.; Banks, L.M.; Bright, T.; Dionicio, C.; Hameed, S.; Neupane, S.; Murthy, G.; Orucu, A.; Oye, J.; et al. Interrogating and Reflecting on Disability Prevalence Data Collected Using the Washington Group Tools: Results from Population-Based Surveys in Cameroon, Guatemala, India, Maldives, Nepal, Turkey and Vanuatu. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prynn, J.E.; Dube, A.; Mwaiyeghele, E.; Mwiba, O.; Geis, S.; Koole, O.; Nyirenda, M.; Kuper, H.; Crampin, A.C. Self-reported disability in rural Malawi: Prevalence, incidence, and relationship to chronic conditions. Wellcome Open Res. 2021, 4, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprunt, B.; Hoq, M.; Sharma, U.; Marella, M. Validating the UNICEF/Washington Group Child Functioning Module for Fijian schools to identify seeing, hearing and walking difficulties. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 41, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprunt, B.; McPake, B.; Marella, M. The UNICEF/Washington Group Child Functioning Module—Accuracy, Inter-Rater Reliability and Cut-Off Level for Disability Disaggregation of Fiji’s Education Management Information System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mörchen, M.; Zambrano, O.; Páez, A.; Salgado, P.; Penniecook, J.; Von Lindau, A.B.; Lewis, D. Disability-Disaggregated Data Collection: Hospital-Based Application of the Washington Group Questions in an Eye Hospital in Paraguay. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mopari, R.; Garg, B.; Puliyel, J.; Varughese, S. Measuring disability in an urban slum community in India using the Washington Group questionnaire. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. Translation of the Washington Group Tools. 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/fileadmin/uploads/wg/Documents/WG_Implementation_Document__3_-_Translation_of_the_Washington_Group_Tools.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. Analysis Overview. Available online: https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/about/about-the-wg/ (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. Overview of Implementation Protocols for Testing the Washington Group Short Set of Questions on Disability. 2016. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/washington_group/meeting6/main_implementation_protocol.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Principles and Recommendations for Population and Housing Censuses Revision 3; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/Standards-and-Methods/files/Principles_and_Recommendations/Population-and-Housing-Censuses/Series_M67rev3-E.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Washington Group on Disability. The Washington Group Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS). 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/fileadmin/uploads/wg/Documents/Questions/new-_WG_Implementation_Document__2_-_The_Washington_Group_Short_Set_on_Functioning__1_.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- United Nations Population Fund. People with Disabilities in Vet Nam: Key findings from the 2009 Viet Nam Population and Housing Census; United Nations Population Fund: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2001; Available online: https://vietnam.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Disability_ENG.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Leonard Cheshire and Humanity and Inclusion. Disability Data Collection: A Summary Review of the Use of the Washington Group Questions by Development and Humanitarian Actors; Leonard Cheshire and Humanity and Inclusion: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://humanity-inclusion.org.uk/sn_uploads/document/2018-10-summary-review-wgq-development-humanitarian-actors.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2021).

| Topics | Codes (Not Exhaustive) | Themes |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Characteristics and Use of the WGQ | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of organization | International NGOs (INGOs) | 11 |

| National NGOs | 5 | |

| Organizations of People with Disability | 4 | |

| Others (e.g., managing contractor, consultancy firms) | 6 | |

| Disability focused organization | Yes | 20 |

| No (4 INGOs & 2 other types of organization) | 6 | |

| Size of organization | <10 people | 6 |

| 10 to 29 people | 5 | |

| 30 to 99 people | 5 | |

| >100 people | 7 | |

| Missing data | 3 | |

| Geographical areas the questions were used a | Pacific | 5 |

| South Asia | 5 | |

| Southeast Asia | 4 | |

| Other parts of Asia | 2 | |

| Middle East & North Africa | 2 | |

| Other parts of Africa | 5 | |

| America & Europe | 1 | |

| Disability question sets used a | WG Short Set | 22 |

| WG Extended Set | 7 | |

| WG/UNICEF Child Functioning Module | 5 | |

| Rapid Assessment of Disability Toolkit (RAD) | 4 | |

| Purpose of using the questions a | Program design | 9 |

| Implementation | 18 | |

| Monitoring & Evaluation | 19 | |

| Advocacy | 9 | |

| Programming areas a | Education & Training | 12 |

| Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) | 9 | |

| Humanitarian Response | 6 | |

| Work & Livelihoods | 6 | |

| Human Rights (advocacy) | 6 | |

| Health | 5 | |

| Water Sanitation & Hygiene (WASH) | 5 | |

| Others (e.g., elimination of violence against women, child protection) | 7 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Robinson, A.; Nguyen, L.; Smith, F. Use of the Washington Group Questions in Non-Government Programming. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111143

Robinson A, Nguyen L, Smith F. Use of the Washington Group Questions in Non-Government Programming. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111143

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobinson, Alex, Liem Nguyen, and Fleur Smith. 2021. "Use of the Washington Group Questions in Non-Government Programming" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111143

APA StyleRobinson, A., Nguyen, L., & Smith, F. (2021). Use of the Washington Group Questions in Non-Government Programming. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11143. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111143