Differences in Perceived Risk of Contracting SARS-CoV-2 during and after the Lockdown in Sub-Saharan African Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Measures

2.3. Assessment of Risks about COVID-19

2.4. Ethical Consideration

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

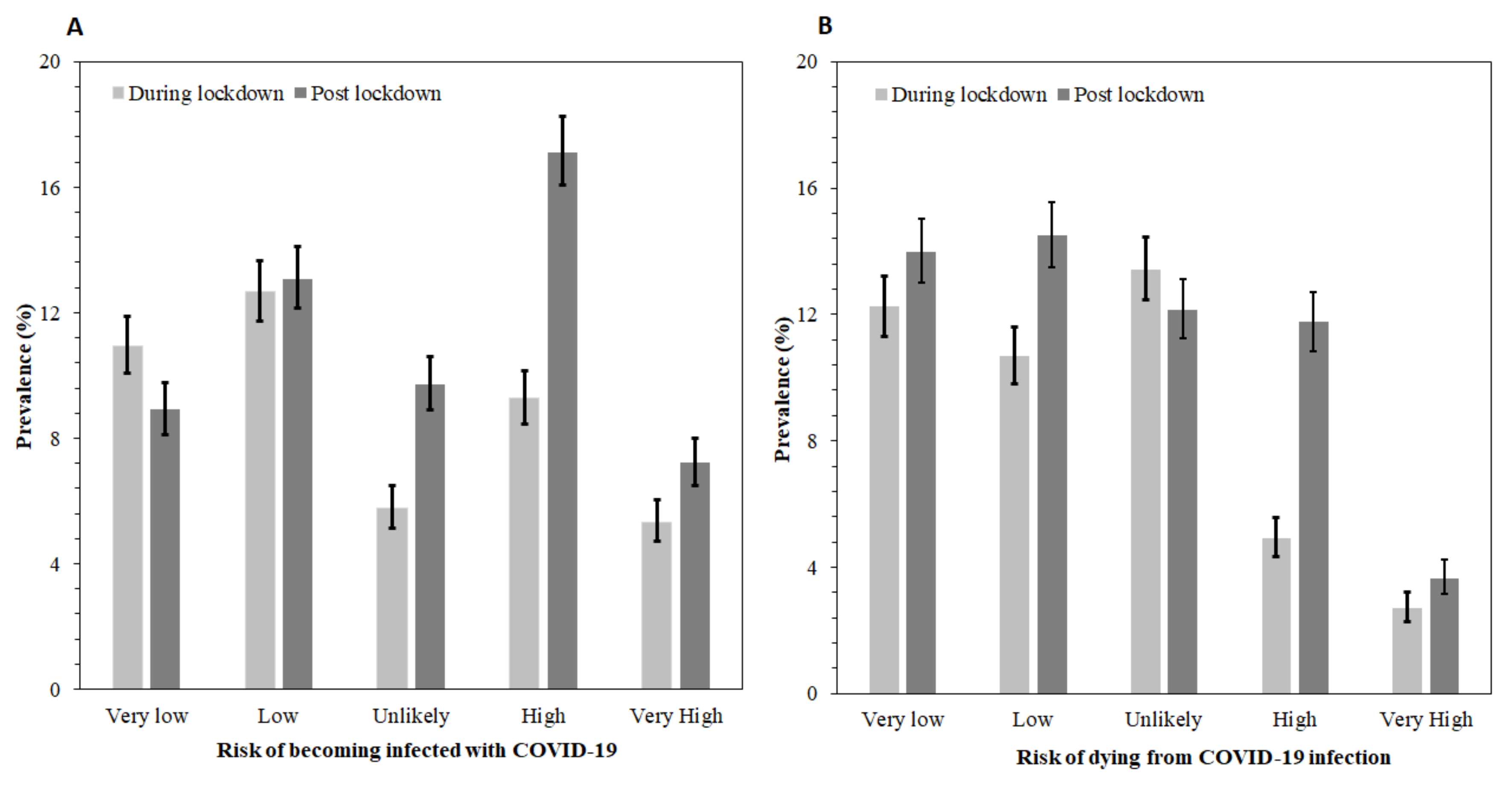

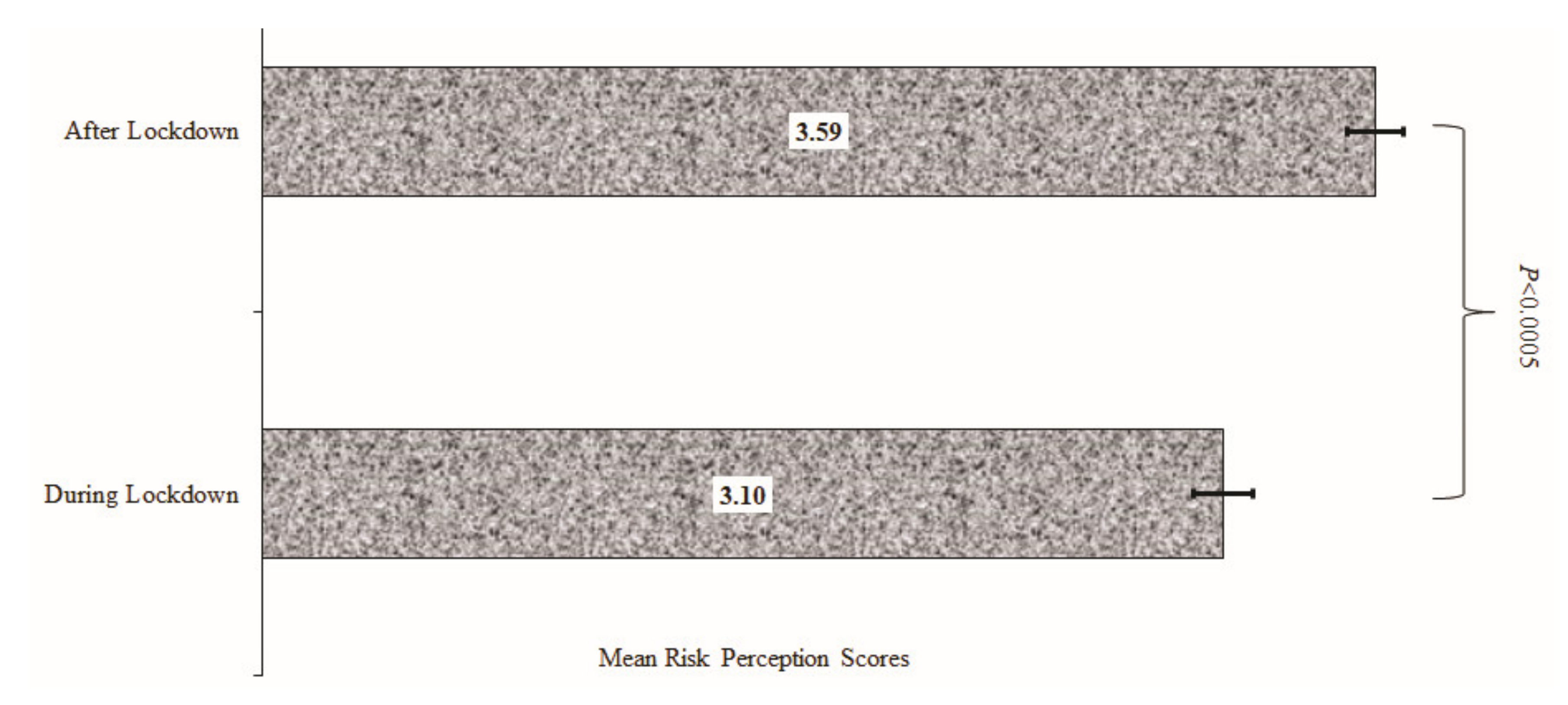

3.2. Mean Scores and Unadjusted Factors of Risk Perception for Contracting COVID-19

3.3. Factors Associated with Perceived Risk for Contracting COVID-19 during Lockdown and Post-Lockdown

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xia, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Lan, Q.; Feng, S.; Qi, F.; Bao, L.; Du, L.; Liu, S. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olshaker, M.; Osterholm, M.T. Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs; Hachette: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/ (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Chang, S.L.; Harding, N.; Zachreson, C.; Cliff, O.M.; Prokopenko, M. Modelling transmission and control of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Maintaining Essential Health Services: Operational Guidance for the COVID-19 Context: Interim Guidance, 1 June 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, J.L. Evaluating and deploying COVID-19 vaccines—The importance of transparency, scientific integrity, and public trust. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1703–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD.org. Enhancing Public Trust in COVID-19 Vaccination: The Role of Governments. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/enhancing-public-trust-in-covid-19-vaccination-the-role-of-governments-eae0ec5a/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Adams, J.; MacKenzie, M.J.; Amegah, A.K.; Ezeh, A.; Gadanya, M.A.; Omigbodun, A.; Sarki, A.M.; Thistle, P.; Ziraba, A.K.; Stranges, S. The Conundrum of Low COVID-19 Mortality Burden in sub-Saharan Africa: Myth or Reality? Glob. Health: Sci. Pract. 2021, 9, 433–443. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Older Adults Risks and Vaccine Information Center for Disease Control. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/covid19/covid19-older-adults.html (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Williamson, E.J.; Walker, A.J.; Bhaskaran, K.; Bacon, S.; Bates, C.; Morton, C.E.; Curtis, H.J.; Mehrkar, A.; Evans, D.; Inglesby, P. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020, 584, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, B.; Gates, M. Our 2019 Annual Letter—Compact 2025 Resources—IFPRI Knowledge Collections. 2019. Available online: https://ebrary.ifpri.org/digital/collection/p15738coll16/id/1082/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Adamchak, D.J. Population aging in sub-Saharan Africa: The effects of development on the elderly. Popul. Environ. 1989, 10, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaja, I.F.; Anyanwu, M.U.; Iwu Jaja, C.-J. Social distancing: How religion, culture and burial ceremony undermine the effort to curb COVID-19 in South Africa. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1077–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J. The faith community and the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: Part of the problem or part of the solution? J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 2215–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buheji, M. Stopping future COVID-19 like pandemics from the Source-A Socio-Economic Perspective. Am. J. Econ 2020, 10, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Fahad, S.; Faisal, S.; Naushad, M. Quarantine role in the control of corona virus in the world and its impact on the world economy. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moti, U.G.; Ter Goon, D. Novel Coronavirus Disease: A delicate balancing act between health and the economy. Pak. J. Med Sci. 2020, 36, S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.W.; Nyengerai, T.; Mendenhall, E. Evaluating the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: Perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and childhood trauma predict adult depressive symptoms in urban South Africa. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu, E.K.; Oloruntoba, R.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Bhattarai, D.; Miner, C.A.; Goson, P.C.; Langsi, R.; Nwaeze, O.; Chikasirimobi, T.G.; Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G.O. Risk perception of COVID-19 among sub-Sahara Africans: A web-based comparative survey of local and diaspora residents. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G.O.; Ishaya, T.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Abu, E.K.; Nwaeze, O.; Oloruntoba, R.; Ekpenyong, B.; Mashige, K.P.; Chikasirimobi, T.G.; Langsi, R. Factors associated with the myth about 5G network during COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. J. Glob. Health Rep. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, T.J.; Andrews, K.D. Traditional, Likert, and simplified measures of self-efficacy. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, W.M. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar]

- McGough, J.J.; Faraone, S.V. Estimating the size of treatment effects: Moving beyond p values. Psychiatry 2009, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Emslie, G.J.; Rush, A.J.; Weinberg, W.A.; Kowatch, R.A.; Hughes, C.W.; Carmody, T.; Rintelmann, J. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, R.A.; Klein, W.M. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Attema, A.E.; L’Haridon, O.; Raude, J.; Seror, V.; The COCONEL Group. Beliefs and Risk Perceptions About COVID-19: Evidence From Two Successive French Representative Surveys During Lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 619145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscusi, W.K. Are individuals Bayesian decision makers? Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Wouters, O.J.; Shadlen, K.C.; Salcher-Konrad, M.; Pollard, A.J.; Larson, H.J.; Teerawattananon, Y.; Jit, M. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: Production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet 2021, 397, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidere, M.F.; Ratan, Z.A.; Nowroz, S.; Zaman, S.B.; Jung, Y.-J.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Cho, J.Y. COVID-19 vaccine: Critical questions with complicated answers. Biomol. Ther. 2021, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 Perceptions, Stigma and Impact; Ministry of Health: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020.

- Clark, A.; Jit, M.; Warren-Gash, C.; Guthrie, B.; Wang, H.H.; Mercer, S.W.; Sanderson, C.; McKee, M.; Troeger, C.; Ong, K.L. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: A modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1003–e1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drefahl, S.; Wallace, M.; Mussino, E.; Aradhya, S.; Kolk, M.; Brandén, M.; Malmberg, B.; Andersson, G. A population-based cohort study of socio-demographic risk factors for COVID-19 deaths in Sweden. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, A.J.; Ferrer, R.A.; Welch, J.D. Associations between narrative transportation, risk perception and behaviour intentions following narrative messages about skin cancer. Psychol. Health 2018, 33, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzen, A.; Wöhner, F. Coronavirus risk perception and compliance with social distancing measures in a sample of young adults: Evidence from Switzerland. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaxman, A.D.; Henning, D.J.; Duber, H.C. The relative incidence of COVID-19 in healthcare workers versus non-healthcare workers: Evidence from a web-based survey of Facebook users in the United States. Gates Open Res. 2020, 4, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Klein, E.J.; Kollars, K.; Kleinhenz, A.L. Medical students are not essential workers: Examining institutional responsibility during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 1149–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpenyong, B.; Obinwanne, C.J.; Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G.; Ahaiwe, K.; Lewis, O.O.; Echendu, D.C.; Osuagwu, U.L. Assessment of knowledge, practice and guidelines towards the Novel COVID-19 among eye care practitioners in Nigeria—A survey-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain-Dupré, D.; Chatry, I.; Michalun, V.; Moisio, A. The Territorial Impact of COVID-19: Managing the Crisis Across Levels of Government; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, L.; Niu, J.; Bi, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Ning, N.; Liang, L.; Liu, A.; Hao, Y. The impacts of knowledge, risk perception, emotion and information on citizens’ protective behaviors during the outbreak of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddlestone, M.; Green, R.; Douglas, K.M. Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 59, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knief, U.; Forstmeier, W. Violating the normality assumption may be the lesser of two evils. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuagwu, U.L.; Miner, C.A.; Bhattarai, D.; Mashige, K.P.; Oloruntoba, R.; Abu, E.K.; Ekpenyong, B.; Chikasirimobi, T.G.; Goson, P.C.; Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G.O. Misinformation About COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Survey. Health Secur. 2021, 19, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abir, T.; Kalimullah, N.A.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Yazdani, D.M.N.-A.; Mamun, A.A.; Husain, T.; Basak, P.; Permarupan, P.Y.; Agho, K.E. Factors Associated with the Perception of Risk and Knowledge of Contracting the SARS-Cov-2 among Adults in Bangladesh: Analysis of Online Surveys. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | Total (N = 4551) | During Lockdown (n = 2001) | Post-Lockdown (n = 2550) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age category in years | |||

| 18–28 years | 1697 (38.0) | 774(39.1) | 923 (37.2) |

| 29–38 | 1242 (27.8) | 526 (26.5) | 716 (28.9) |

| 39–48 | 939 (21.1) | 439 (22.2) | 500 (20.2) |

| 49+ years | 584 (13.1) | 242 (12.2) | 342 (13.8) |

| Sex | |||

| Males | 2467 (54.5) | 1095 (55.2) | 1372 (53.8) |

| Females | 2057 (45.5) | 889 (44.8) | 1168 (45.8) |

| SSA Region of Origin | |||

| West Africa | 2572(56.5) | 1122 (56.1) | 1450 (56.9) |

| East Africa | 347(7.6) | 212 (10.6) | 135 (5.3) |

| Central Africa | 570 (12.5) | 253 (12.6) | 317 (12.4) |

| Southern Africa | 1062 (23.3) | 414 (20.7) | 648 (25.4) |

| Country of residence | |||

| Africa | 4250 (93.6) | 1852 (92.6) | 2398 (94.4) |

| Diaspora | 291 (6.4) | 149 (7.4) | 142 (5.6) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/de facto | 2003 (44.3) | 876 (44.1) | 1127 (44.4) |

| Not married † | 2522 (55.7) | 1112 (55.9) | 1410 (55.6) |

| Educational status | |||

| Master’s degree or more ‡ | 1383 (30.7) | 639 (32.1) | 744 (29.5) |

| Bachelor’s degree α | 2383 (52.9) | 1086 (54.6) | 1297 (51.5) |

| Secondary/primary | 741 (16.4) | 264 (13.3) | 477 (19.0) |

| Working status | |||

| Employed/self employed | 3001 (66.9) | 1353 (68.0) | 1648 (65.9) |

| Unemployed/retired | 1488 (33.1) | 636 (32.0) | 852 (33.1) |

| Religion | |||

| Christianity | 4042 (89.7) | 1758 (88.4) | 2284 (90.8) |

| Others ᵖ | 462 (10.3) | 230 (11.6) | 232(9.2) |

| Occupation β | |||

| Healthcare sector | 1240 (31.5) | 443 (24.3) | 797 (37.6) |

| Non-healthcare | 1602 (40.6) | 1014 (55.7) | 588 (27.7) |

| Student | 1099 (27.9) | 364 (20.0) | 735 (34.7) |

| Variables | Mean Scores (±SD) | B [95%CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survey period | |||

| Period 1 (during lockdown) | 3.10 (2.19) | Ref | |

| Period 2 (post-lockdown) | 3.59 (2.36) | 0.49 [0.36, 0.62] | <0.001 |

| Demography | |||

| Age category in years | |||

| 18–28 years | 3.13 (2.24) | Ref | |

| 29–38 | 3.51 (2.31) | 0.38 [0.22, 0.55] | <0.001 |

| 39–48 | 3.57 (2.35) | 0.44 [0.26, 0.63] | <0.001 |

| 49+ years | 3.58 (2.30) | 0.45 [0.23, 0.66] | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Males | 3.42 (2.32) | Ref | |

| Females | 3.34 (2.27) | −0.08 [−0.22, 0.005] | 0.226 |

| SSA Region of Origin | |||

| West Africa | 3.26 (2.24) | Ref | |

| East Africa | 3.78 (2.41) | 0.51 [0.26, 0.77] | <0.001 |

| Central Africa | 3.22 (2.44) | −0.05 [−0.26, 0.16] | 0.658 |

| Southern Africa | 3.61 (2.30) | 0.35 [0.19, 0.52] | <0.001 |

| Country of residence | |||

| Africa | 3.39 (2.30) | Ref | |

| Diaspora | 3.26(2.23) | −0.13 [−0.40, 0.15] | 0.360 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 3.52(2.30) | Ref | |

| Not married | 3.27(2.30) | −0.25 [−0.39, −0.12] | <0.001 |

| Educational status | |||

| Master’s degree or more | 3.50(2.25) | Ref | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 3.37(2.32) | −0.13 [−0.28, 0.02] | 0.089 |

| Secondary/Primary | 3.20 (2.32) | −0.31 [−0.51, −0.10] | 0.004 |

| Working status | |||

| Employed/self employed | 3.54 (2.30) | Ref | |

| Unemployed/retired | 3.10 (2.26) | −0.43 [−0.57, −0.29] | <0.001 |

| Religion | |||

| Christianity | 3.37(2.30) | Ref | 0.676 |

| Others | 3.42(2.29) | 0.05 [−0.17, 0.27] | |

| Occupation | |||

| Healthcare sector | 3.83 (2.34) | Ref | |

| Non-healthcare | 3.20 (2.23) | −0.63 [−0.80, −0.46] | <0.001 |

| Student | 3.09 (2.24) | −0.75 [−0.93, −0.56] | <0.001 |

| Variables | β [95%CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Year of survey | ||

| Period 1 (during lockdown) | Ref | |

| Period 2 (post-lockdown) | 0.42 [0.27, 0.57] | <0.001 |

| Demography | ||

| Age category in years | ||

| 18–28 years | Ref | |

| 29–38 | 0.25 [0.04, 0.46] | 0.020 |

| 39–48 | 0.31 [0.08, 0.54] | 0.010 |

| 49+ years | 0.31 [0.05, 0.58] | 0.020 |

| SSA Region of Origin | ||

| West Africa | Ref | |

| East Africa | 0.55 [0.28, 0.82] | <0.001 |

| Central Africa | 0.08 [−0.15, 0.31] | 0.490 |

| Southern Africa | 0.37 [0.19, 0.54] | <0.001 |

| Occupation | ||

| Healthcare sector | Ref | |

| Non-healthcare | −0.56 [−0.73, −0.38] | <0.001 |

| Student | −0.60 [−0.82, −0.38] | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Osuagwu, U.L.; Timothy, C.G.; Langsi, R.; Abu, E.K.; Goson, P.C.; Mashige, K.P.; Ekpenyong, B.; Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G.O.; Miner, C.A.; Oloruntoba, R.; et al. Differences in Perceived Risk of Contracting SARS-CoV-2 during and after the Lockdown in Sub-Saharan African Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111091

Osuagwu UL, Timothy CG, Langsi R, Abu EK, Goson PC, Mashige KP, Ekpenyong B, Ovenseri-Ogbomo GO, Miner CA, Oloruntoba R, et al. Differences in Perceived Risk of Contracting SARS-CoV-2 during and after the Lockdown in Sub-Saharan African Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111091

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsuagwu, Uchechukwu Levi, Chikasirimobi G Timothy, Raymond Langsi, Emmanuel K Abu, Piwuna Christopher Goson, Khathutshelo P Mashige, Bernadine Ekpenyong, Godwin O Ovenseri-Ogbomo, Chundung Asabe Miner, Richard Oloruntoba, and et al. 2021. "Differences in Perceived Risk of Contracting SARS-CoV-2 during and after the Lockdown in Sub-Saharan African Countries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111091

APA StyleOsuagwu, U. L., Timothy, C. G., Langsi, R., Abu, E. K., Goson, P. C., Mashige, K. P., Ekpenyong, B., Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G. O., Miner, C. A., Oloruntoba, R., Ishaya, T., Charwe, D. D., Envuladu, E. A., Nwaeze, O., & Agho, K. E. (2021). Differences in Perceived Risk of Contracting SARS-CoV-2 during and after the Lockdown in Sub-Saharan African Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111091