Abstract

There is growing evidence on the observed and expected consequences of climate change on population health worldwide. There is limited understanding of its consequences for child health inequalities, between and within countries. To examine these consequences and categorize the state of knowledge in this area, we conducted a review of reviews indexed in five databases (Medline, Embase, Web of Science, PsycInfo, Sociological Abstracts). Reviews that reported the effect of climate change on child health inequalities between low- and high-income children, within or between countries (high- vs low–middle-income countries; HICs and LMICs), were included. Twenty-three reviews, published between 2007 and January 2021, were included for full-text analyses. Using thematic synthesis, we identified strong descriptive, but limited quantitative, evidence that climate change exacerbates child health inequalities. Explanatory mechanisms relating climate change to child health inequalities were proposed in some reviews; for example, children in LMICs are more susceptible to the consequences of climate change than children in HICs due to limited structural and economic resources. Geographic and intergenerational inequalities emerged as additional themes from the review. Further research with an equity focus should address the effects of climate change on adolescents/youth, mental health and inequalities within countries.

1. Introduction

The uneven distribution of social and environmental factors on birth and early life give rise to avoidable child health inequalities [1]. Differences in child survival, health, development and well-being are stark between low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries (HICs) [2]. Many children in LMICs live in circumstances in which they are deprived of essential determinants of health such as clean air, adequate shelter, nutrition, safe water and sanitation [3], all of which contribute to the higher risk of adverse child health outcomes such as stunting secondary to malnutrition [4], acute respiratory illness [5], diarrheal disease [6] and vector-borne diseases such as malaria [7]. Despite improvement in child survival rates within these countries, children from poorer households remain disproportionately vulnerable: on average, the risk of dying before age 5 is twice as high for children born into the poorest households as it is for those born into the richest [3]. Inequalities within HICs exist as well with many children in low-income households experiencing high levels of air pollution [8], food insecurity [9] and poor housing conditions [10].

Climate change is an ongoing urgent global problem. The recently published sixth assessment Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [11] asserts that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions have been responsible for an increase in yearly average temperatures across the world currently estimated at 1.2 °C over pre-industrial temperature levels. Without mitigation, global temperature change will likely increase by 1.5 °C by 2030 and may increase 4.8 °C by 2100. Observable planetary changes due to climate change including glaciers melting, water levels rising, prolonged heat waves, floods, droughts and rainfall have accelerated in 2020–21 with uncontrolled wild fires in the west coast of North America, parts of Australia and southern Europe and unprecedented flooding in China and central Europe.

Global warming and its consequences are now accepted as a significant threat to global health and well-being, and children are known to be particularly vulnerable to its effects [12]. In 2009, Lancet Commission on Climate Change determined that climate change is the biggest global health threat of the 21st century [13]. The commission concluded that most health impacts will be adverse and will occur via direct exposures (e.g., heat waves, extreme weather events) but also by significantly impacting basic social determinants of health. The commission further identified certain populations as “vulnerable” to climate change such as the elderly, children, individuals with underlying health conditions and populations in LMICs. Focusing on children more specifically, a scoping review published after the end date of our search [14], identified the range of childhood conditions exacerbated by direct and indirect effects of climate change, for example, vector-, water- and food-borne infectious diseases and mental health problems.

We conducted a scoping review of published review articles with the aim of assessing the strength of evidence for the extent and mechanisms by which climate change and its consequences differentially impact children in social groups within countries and in poorer compared with richer countries and identify knowledge gaps. The main research questions of the review were: What is the current state of knowledge on the impact of climate change and its consequences on child health inequalities? What is the evidence that climate change exacerbates child health inequalities? Is the evidence reported in the reviews supported by quantitative data comparing the impact of climate change and its consequences on different social groups within countries and/or between countries? Are the mechanisms by which climate change and its consequences may exacerbate and/or generate child health inequalities addressed in the included reviews?

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a scoping review, guided by the methodology outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [15], to examine the main research questions listed above. The population of interest is children aged 0–18 years, the key concepts are climate change and inequalities in child health and the contexts of interest are social groups within countries, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) compared to high-income countries (HICs) and geographical locations.

The scoping review approach was favored as it allows researchers to, “identify, retrieve and summarize literature relevant to a particular topic for the purpose of identifying the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available” [15] ( p. 14). In recent years there have been advancements in the methodology [16] and a rapid increase in its application due to its wide range of uses [17]. According to Arksey and O’Malley, two features of a scoping review contrast it from a systematic review. First, where systematic reviews have a well-defined question and may examine a particular type of study design, a scoping review addresses broader questions, allowing the researcher to identify and map key concepts of an area, and may include various study designs. Second, unlike a systematic review, a scoping review does not include a quality assessment of the included studies. Arksey and O’Malley further suggest that scoping reviews may have one of two purposes, either to serve as a first step towards a subsequent systematic review or research project, or it may be conceived as a method in its own right, to identify key concepts or gaps in the existing evidence and define the main sources of evidence.

Building on the scoping review approach, we chose to scope reviews rather than primary literature. The ”review of reviews” approach is efficient when aiming to capture how a concept is described in the literature and to map out emerging themes, rather than relying on primary literature. Examples of applications are in the examination of loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults [18] and mental health promotion interventions [19].

In partnership with the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, we led a review of peer-reviewed reviews indexed in five databases (Medline, Embase, Web of Science, PsycInfo, Proquest). The search was conducted from database start dates to 21 January 2021. Search terms used for all databases are shown in the supplementary files (Tables S1 and S2). We defined climate change in broad terms. Examples of search terms were “Climate Change”, “Greenhouse Effect”, “Hot Temperature”, “Natural disaster”, “Heat wave” and “Wildfire”. The population of interest was children and young people less than 18 years old which we defined according to the age definition of the UN Convention of the Child [20]. We considered a range of health conditions, including physical ailments, infectious diseases and mental health conditions. Mental health was defined broadly with the inclusion of disorders as well as psychological consequences of climate change. We defined inequalities in relation to specific indicators such as socioeconomic status, income, wealth, poverty, ethnicity and indigenous status within and between countries. There were no limits on years of publication nor languages.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

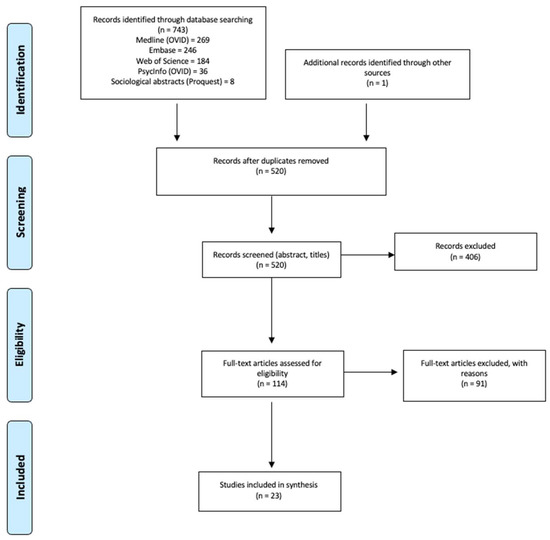

Our search strategy retrieved 743 reviews, with 520 reviews after deduplication. Though not retrieved in the initial search, one additional review article was included for its relevance to the topic and objective. Title and abstract evaluations rendered 114 reviews eligible for full-text analysis. Papers for full text analysis were allocated to groups of two researchers, each to undertake review and reach consensus. Disagreements were resolved by whole group decision. Following this, 91 articles were excluded leaving 23 reviews that were included for synthesis. The results of the review process are presented as a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1. In addition, we followed the charting approach described by Arksey and O’Malley and Levac et al. to synthesize results and comment on emerging themes.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

The primary theme of interest in the scoping review was the association of climate change and child health inequalities reported in three specific dimensions; within country differences by social groups, between country differences (LMICs vs. HICs), and living in specific geographical locations. For within country inequalities, we sought evidence that reviews identified the impact of climate change on children in social groups by relative advantage versus disadvantage. For between country inequalities, we explored how reviews reported and explained the differential impact of climate change on child health in LMICs compared with HICs. Geographical location was explored as a dimension of inequality as children living in these areas were identified as at increased risk of adverse health outcomes resulting from climate change. In all these dimensions of inequality, we sought supporting quantitative and/or descriptive evidence of exacerbation of existing child health inequalities by climate change and evidence of the mechanisms by which climate change impacts child health inequalities. Definitions and descriptions of climate change and of child health in the reviews were explored as secondary themes.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

Of the included reviews, four were systematic reviews (Table 2) [21,22,23,24], three were technical and commissioned reports (Table 3) [13,25,26] and 16 were narrative reviews, or opinion pieces with substantive literature reviews (Table 4) [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. All reviews and reports were published in international peer-reviewed journals with the exception of the Assembly of First Nations Report which was included as the challenges faced by indigenous children and their families are under-represented in the literature. Sixteen reviews had a global focus incorporating LMICs and HICs [13,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,34,35,37,39,40,42], four reviews had a specific country focus (US [21], Canada [26,33], Cambodia [41]) and three reviews focused on grouped nations of a specific world region (LMICs [22,24], Sub-Saharan Africa, North America). Reviews were published from 2007 to 2020 and all were published in English.

Table 2.

Systematic reviews.

Table 3.

Technical and commissioned reports.

Table 4.

Narrative reviews and opinion pieces.

3.2. Child Health Inequalities

3.2.1. Within Country Inequalities

Within country inequalities in child health related to climate change were reported in 16 reviews [13,21,22,23,24,26,27,28,29,31,33,35,37,40,41,42]. All reviews included descriptive evidence and five included quantitative evidence [13,23,24,25,41]. Compared with more advantaged groups, children in poor, low income, low educated, socioeconomically marginalized households and those in indigenous and traditional societies, were identified as more likely to suffer consequences of climate change. Bennett and Friel [42] concluded that climate change acts as an amplifier of existing inequities with the result that the world’s poorest and socially-disadvantaged children will bear the greatest burden of climate change-related ill-health. Chersich et al. [23] reported that Korean women with both low education levels and low socioeconomic status had a 1.1-fold increased hazard ratio of preterm birth for each quartile increase in temperature compared with more socioeconomically advantaged women. Ahdoot and Pacheco [25] stated that the world’s poorest children are up to 10 times more likely to be affected by climate change associated weather disasters compared to children in higher-income families due to limited material and financial resources. Following floods in 2011, Cambodian children from households with poor sanitation and untreated drinking water as well as having a mother who lacked education experienced higher rates of diarrhea than households with treated water, soap and more highly educated mothers [41]. Lieber et al. [24] quantify the moderating effects of low socioeconomic status (−0.6) and high maternal education (+0.9) on childhood malnutrition although the exact metric used is not stated.

Four of the 13 included articles in Benevolenza and DeRigne’s systematic review [21] discussed the negative impact of climate change, specifically increased frequency and severity of hurricanes, on low-resourced/low-income parents and children. The authors found that children from low-income families and families led by single mothers are likely to suffer from more adverse mental, emotional and physical health problems than their more advantaged peers although, as the authors acknowledge, there was an absence, in all included studies, of statistics comparing disadvantaged with advantaged populations.

3.2.2. Between Country Inequalities

Between country inequalities, comparing LMICs with HICs, were reported in 16 reviews [13,23,24,25,27,31,32,34,35,36,38,39,40]. All reported descriptive evidence and three reported quantitative evidence [13,23,25]. Ahdoot and Pacheco [25] reported climate change will increase the diarrheal disease burden leading to an estimated 48,000 additional deaths attributable to diarrheal disease in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa by 2030. In African populations, loss of healthy life years is predicted to be 500 times greater than in European populations as a result of climate change with devastating effects on African children’s life chances [13]. Anderko et al. [38] identify food insecurity as a consequence of extreme weather events and changes in temperature and precipitation patterns damaging and destroying crops, leading to increased malnutrition especially in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Philipsborn and Chan [35], based on the projected increase in diarrhea, malaria and nutritional deficiencies due to climate change, predict that LMICs will experience an increased burden of avoidable death among under 5-year-old children. Rylander et al. [36] predict an increase in the risk of pregnancy complications, preterm delivery and low birthweight due to the expected increase in incidence of malaria, dengue fever and schistosomiasis among pregnant women in LMICs due to climate change.

3.2.3. Geographic Inequality

The differential impact of climate change on child health was also defined along geographic lines [28,30,31,41]. Kistin et al. [30] discussed an increasing risk of flooding and water scarcity as a result of increasing temperatures, earlier thawing of snowpack and glaciers melting among communities in mountainous regions. Levy and Patz [31] highlighted climate change threats to coastal regions from rising sea levels. Another study found that children living in usually cooler climates will begin to become more vulnerable to climate change related illnesses and infections, such as Lyme disease and Dengue [28].

3.2.4. Intergenerational Inequity

An additional dimension of inequality affecting children was identified by Ebi and Paulson [28] who defined ‘intergenerational inequity’, where children are considered to be a particularly disadvantaged population, not only because of physiological and developmental vulnerability, but also because their higher likelihood of experiencing severe effects of climate change in the future. McMichael [32] suggests that children will inevitably be exposed to adverse health effects for a greater portion of their lives than adults and will suffer the consequences of actions in which they have played little or no part. As such, the particular vulnerability of children to the detrimental effects of climate change may be regarded, not only as a result of young age, but also as a cohort effect.

3.3. Explanatory Mechanisms

Bennett and Friel [42] demonstrate how differential access to protective factors determined by family financial and social resources ensure that the child from a high-income family is less likely to be exposed to the worst effects of heat, flooding and other consequences of extreme weather events. As vector-borne diseases become more prevalent as a result of climate change, poor and disadvantaged children are at increased risk due to lifelong poverty, persistent malnutrition, insanitary living conditions and lack of preventive health measures.

The increased impact of climate change on child health in LMICs is attributed in the reviews to factors such as low levels of maternal education and poor water sanitation, poor infrastructure (e.g., air quality control, pollution control), weak economy, as well as poor political leadership and democratic institutions. Some reviews characterized LMICs as having a “double burden” of climate change based on their higher exposure to extreme weather events and on their limited capacity to mitigate the negative effects of climate change due to scarce structural economic and political resources [13,22,32,35,39].

A number of reviews postulated ‘direct’ effects and ‘indirect’ effects of climate change on child health [24,25,27,32]. Direct effects are the immediate impacts that climate change will have on children, while indirect effects are the impacts that climate change will have on important social determinants of health for children with downstream effects on child health. For example, the reduction in water supply following a severe weather event due to climate change will impact the food supply which can lead to childhood malnutrition and stunting over time. McMichael [32] further suggests that there are diffuse or ‘tertiary’ effects of climate change, which are further downstream effects such as physical displacement, impaired recreational facilities and limited opportunities for children.

3.4. Climate Change

We identified the variation in how climate change was defined across included reviews as a secondary theme. Although definitions varied, all are recognized as climate change and/or its consequences in the IPCC report [11]. The majority of reviews (14 reviews) discussed climate change as a gradual increase in planetary ambient temperature leading to increases in extreme weather events and summarized their respective health effects [13,26,27,28,29,31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Few reviews explicitly defined and examined a specific feature of climate change. Nine reviews considered discrete weather events that are associated with climate change: increasing hurricane severity and frequency [21], increasing air pollution [25], weather events impacting droughts, floods, rainfalls [22,24,30,31,41,42], and heat waves [23,31,42]. However, the relationship between specific weather events and climate change was not always clear and at times minimized in some of the reviews [21,28].

3.5. Childhood and Child Health

An additional secondary theme to emerge from the reviews was how childhood and child health were defined. Most reviews included all ages from birth to 18, while others focused on children less than 5 years of age [22,34,36] or the antenatal and/or perinatal periods [23,36,37,38,40]. Reviews emphasized children’s vulnerability to the health effects of climate change, compared to adults, due to their incomplete physiological and cognitive development, as well as their dependence on parents and/or caregivers [29,36,37,38] and their higher exposure to air, food and water per unit body weight [27,39].

Multiple adverse health conditions were discussed in the reviews: malnutrition [24,30,31,37,38,39], malnutrition with associated stunting and increased susceptibility to infection [22,32], vector-borne diseases [13,25,28,29,30,31,32,35,37], respiratory diseases [13,26,28,31,32,37,39], diarrhea mainly caused by water-borne diseases [13,28,30,41], perinatal health such as gestational age and birth weight [23,36,38,40], and mortality [28,35]. Only three reviews explicitly considered child mental health and cognitive development [21,27,40], where anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and learning disruptions due to displacements were studied. Finally, two reviews focused on indigenous children in Canada considered dimensions of spiritual health, which significantly broadened the definition of child health compared to other reviews [26,33].

4. Discussion

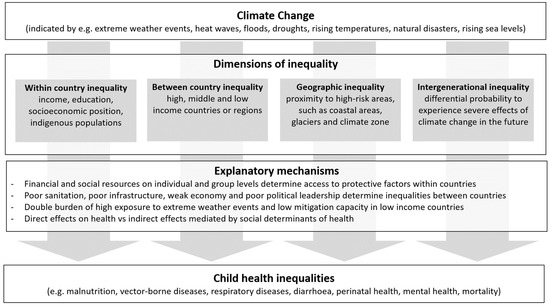

This scoping review of reviews identifies the current level of knowledge and gaps in the literature on the effect of climate change on child health inequalities. Figure 2 presents a graphical representation of the findings of the scoping review.

Figure 2.

Relationship between climate change and child health inequalities.

While inequalities in child health within and/or between countries or geographical regions are touched upon in all the included reviews, few reviews have inequalities as their primary focus. We found descriptive evidence of the differential impact of climate change on children in social groups by relative advantage versus disadvantage within countries and in LMICs compared with HICs; however, quantitative evidence comparing advantaged and disadvantaged children was limited.

Our findings suggest that although inequalities in child health due to climate change are recognized, the literature remains descriptive. For example, Benevolenza and DeRigne [21] describe the greater impact on the health of low-income households of flooding and infrastructure destruction resulting from hurricanes compared with high-income households. However, as the authors acknowledge, none of the studies they reviewed included quantitative evidence of the differential impact. Data on direct consequences of the flooding caused by hurricanes, such as differential hospital admission rates for diarrheal disease by household income among children exposed to the flooding, would provide a better measure of the extent to which hurricanes exacerbate child health inequality.

Understanding the mechanisms by which climate change may exacerbate child health inequalities is key to interventions to minimize its effects. Identification of specific pathways from climate change to child health inequalities using Bennett and Friel’s approach [42] is likely to inform interventions to modify amplification of inequalities by climate change. The urgent need for interventions to mitigate the effects of climate change is illustrated by the recent IPCC report [11] and echoed in the editorials published in 200 medical journals calling for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health [43]. Our scoping review has identified the limited capacity of LMICs to mitigate the negative effects of climate change due to scarce structural economic and political resources and, as demanded by the medical journal editorials [43], enhanced interventions by high income countries will be necessary to promote and fund mitigation and adaptation in LMICs, including improving the resilience of health systems.

Our review finds that much of the literature examines child physical health and infectious diseases, with little focus on child mental health and cognitive development. Most literature is focused on younger children, in particular less than 5 years of age. Children in these age groups are more vulnerable due to their incomplete physiological and cognitive development, but older children are more susceptible to climate change related anxiety.

The strengths of this scoping review of reviews include the development of a robust search strategy based on agreed protocol, as well as a structured screening and selection process based on consensus among the authors. In addition, the scoping review approach enabled us to reach a broad understanding of the state of knowledge and research activity in the area of child health inequalities and climate change. Following the recommendations of Arksey and O’Malley, we are confident that our findings can encourage a subsequent systematic review on this topic. Finally, our review had a lot of breadth and depth by assessing the impact of climate change globally.

Several limitations should be taken into account. The scoping review methodology precludes assessment of study quality in order to avoid focus on a hierarchy of evidence at the expense of breadth of evidence in an under-researched field. Establishing causal associations between climate change and inequalities in children’s health was not possible from existing evidence. The impact of climate change is dynamic with various exposures acting over long periods of time and few of the included reviews accounted for these aspects, except for those that emphasized “indirect” mechanisms. However, in the studies analyzed, a consistent, plausible relationship has been presented.

The review has identified knowledge gaps, including limited quantitative evidence of the impact of climate change across socioeconomic groups and between countries, limited examination and understanding of the mechanisms by which climate change exacerbates child health inequalities and minimal focus on the effect of climate change on child health inequalities for older children and on mental health. A program of research to address these gaps will require the measurement of the impact of climate change on child health across socioeconomic groups in defined populations in different settings and between countries and subnational regions. Existing socio-demographic surveys, such as the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) (Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/ (accessed on 8 October 2021)) and other national and regional surveys, could be modified to include relevant data.

Data quality must be considered to improve the validity of results. While maintaining policy and research focus on the most vulnerable children in poor and low resourced families and children in LMICs, it must also be recognized that more children are becoming increasingly vulnerable through various climate patterns. The implications of the relationship of climate change to social determinants of health for policy and research should be explored further. The interactions between social determinants of health and climate change are considered as indirect effects in some reviews [24,25,27,32] and climate change has been characterized as a social determinant of health [44]. Further work should explore how climate change acts both as a social determinant of health and an amplifier of other social determinants to increase child health inequalities, as suggested by Bennett and Friel [42].

5. Conclusions

The findings of the scoping review of reviews allow us to provide answers to the research questions we set out to address. There was agreement across the reviews that children, particularly poor children, and those in LMICs, are vulnerable to climate change; however, the current state of knowledge of the impact of climate change on child health inequalities is weak. Despite general acknowledgement in the included reviews of the likelihood that climate change will exacerbate child health inequalities, the reported evidence was marginal with little in-depth examination of this issue. There was a paucity of quantitative data comparing children across social groups and countries to support the evidence for the impact of climate change on child health inequalities and mechanisms by which climate change generates child health inequalities warrant further exploration. Our findings indicate the need for an enhanced program of research to address the knowledge gaps and provide evidence for effective interventions to mitigate climate change’s impact on child health inequalities. Further investigation of geographical and intergenerational inequality is also warranted.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph182010896/s1, Tables S1 and S2: Search Terms from Scoping Review.

Author Contributions

N.S. convened the research group from members of the International Network for Research in Inequalities in Child Health (INRICH). All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design of the review. A.H. and K.G. created the search strategy in collaboration with librarians at Karolinska Institute and screened the titles and then the abstracts identified by the search. All authors participated in the assessment of full-text articles for eligibility and selection of articles for inclusion. E.A. prepared the initial draft of the paper, N.S. prepared subsequent drafts with contributions from all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Stockholm University Library.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the search and technical support from Gun Brit Knutssön at the Karolinska Institute and Helen Roberts for her suggestions in the early stages of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

Author IC is on the Editorial Board of IJERPH. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, N.; Raman, S.; O’Hare, B.; Tamburlini, G. Addressing inequities in child health and development: Towards social justice. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2019, 3, e000503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Progress for Children No.11. Beyond Averages: Learning from the MDGs; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, I.C.M.; França, G.V.; Barros, A.J.; Amouzou, A.; Krasevec, J.; Victora, C. Socioeconomic Inequalities Persist Despite Declining Stunting Prevalence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaya, S.; Bishwajit, G. Burden of Acute Respiratory Infections Among Under-Five Children in Relation to Household Wealth and Socioeconomic Status in Bangladesh. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinzón-Rondón, A.M.; Zárate-Ardila, C.; Hoyos-Martínez, A.; Ruiz-Sternberg, Á.M.; Velez-Van-Meerbeke, A. Country characteristics and acute diarrhea in children from developing nations: A multilevel study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Njau, J.D.; Stephenson, R.; Menon, M.; Kachur, S.P.; A McFarland, D. Exploring the impact of targeted distribution of free bed nets on households bed net ownership, socio-economic disparities and childhood malaria infection rates: Analysis of national malaria survey data from three sub-Saharan Africa countries. Malar. J. 2013, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hajat, A.; Hsia, C.; O’Neill, M.S. Socioeconomic Disparities and Air Pollution Exposure: A Global Review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pollard, C.M.; Booth, S. Food Insecurity and Hunger in Rich Countries—It Is Time for Action against Inequality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harker, L. Chance of a Lifetime: Impact of Bad Housing on Children’s Lives; Shelter: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I.; et al. (Eds.) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McMichael, A.J.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.H.; Corvalan, C.F.; Ebi, K.L.; Githeko, A.; Scheraga, J.D.; Woodward, A. Climate Change and Human Health: Risks and Responses; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.; Abbas, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Bell, S.; Bellamy, R.; Friel, S.; Groce, N.; Johnson, A.; Kett, M.; et al. Managing the health effects of climate change: Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet 2009, 373, 1693–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helldén, D.; Andersson, C.; Nilsson, M.; Ebi, K.L.; Friberg, P.; Alfvén, T. Climate change and child health: A scoping review and an expanded conceptual framework. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e164–e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakoya, O.A.; McCorry, N.K.; Donnelly, M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: A scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Enns, J.E.; Holmqvist, M.; Wener, P.; Halas, G.; Rothney, J.; Schultz, A.; Goertzen, L.; Katz, A. Mapping interventions that promote mental health in the general population: A scoping review of reviews. Prev. Med. 2016, 87, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OHCHR. Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Benevolenza, M.A.; DeRigne, L. The impact of climate change and natural disasters on vulnerable populations: A systematic review of literature. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2019, 29, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalkey, R.K.; Aranda-Jan, C.; Marx, S.; Höfle, B.; Sauerborn, R. Systematic review of current efforts to quantify the impacts of climate change on undernutrition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E4522–E4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chersich, M.F.; Pham, M.D.; Areal, A.; Haghighi, M.M.; Manyuchi, A.; Swift, C.P.; Wernecke, B.; Robinson, M.; Hetem, R.; Boeckmann, M.; et al. Associations between high temperatures in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirths: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 371, m3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieber, M.; Chin-Hong, P.; Kelly, K.; Dandu, M.; Weiser, S.D. A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the impact of droughts, flooding, and climate variability on malnutrition. Glob. Public Health 2020, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahdoot, S.; Pacheco, S.E.; The Council on Environmental Health Global. Climate Change and Children’s Health. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e1468–e1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Assembly of First Nations. The Health of First Nations Children n.d.:28. Available online: https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/rp-discussion_paper_re_childrens_health_and_the_environment.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2019).

- Clemens, V.; Von Hirschhausen, E.; Fegert, J.M. Report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change: Implications for the mental health policy of children and adolescents in Europe—A scoping review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Paulson, J.A. Climate Change and Children. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2007, 54, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldhagen, J.L.; Shenoda, S.; Oberg, C.; Mercer, R.; Kadir, A.; Raman, S.; Waterston, T.; Spencer, N.J. Rights, justice, and equity: A global agenda for child health and wellbeing. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistin, E.J.; Fogarty, J.; Pokrasso, R.S.; McCally, M.; McCornick, P.G. Climate change, water resources and child health. Arch. Dis. Child. 2010, 95, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.S.; Patz, J.A. Climate Change, Human Rights, and Social Justice. Ann. Glob. Health 2015, 81, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMichael, A.J. Climate Change and Children: Health Risks of Abatement Inaction, Health Gains from Action. Children 2014, 1, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parkes, M.; de Leeuw, S.; Greenwood, M. Warming Up to the Embodied Context of First Nations Health: A Critical Intervention into and Analysis of Health and Climate Change Research. Int. Public Health J. 2010, 2, 477–485. [Google Scholar]

- Patz, J.A.; Gibbs, H.K.; Foley, J.A.; Rogers, J.V.; Smith, K.R. Climate Change and Global Health: Quantifying a Growing Ethical Crisis. EcoHealth 2007, 4, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipsborn, R.P.; Chan, K. Climate Change and Global Child Health. Pediatrics 2018, 141, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rylander, C.; Odland, J.; Øyvind; Sandanger, T.M. Climate change and the potential effects on maternal and pregnancy outcomes: An assessment of the most vulnerable–The mother, fetus, and newborn child. Glob. Health Action 2013, 6, 19538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheffield, P.E.; Landrigan, P.J. Global Climate Change and Children’s Health: Threats and Strategies for Prevention. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderko, L.; Chalupka, S.; Du, M.; Hauptman, M. Climate changes reproductive and children’s health: A review of risks, exposures, and impacts. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 87, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, G.; Murthy, S. Pediatric Critical Care and the Climate Emergency: Our Responsibilities and a Call for Change. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.M.; Metz, G.A. Climate change is a major stressor causing poor pregnancy outcomes and child development. F1000Research 2020, 9, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, G.I.; McIver, L.; Kim, Y.; Hashizume, M.; Iddings, S.; Chan, V. Water-Borne Diseases and Extreme Weather Events in Cambodia: Review of Impacts and Implications of Climate Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bennett, C.M.; Friel, S. Impacts of Climate Change on Inequities in Child Health. Children 2014, 1, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwoli, L.; Baqui, A.H.; Benfield, T.; Bosurgi, R.; Godlee, F.; Hancocks, S.; Horton, R.; Laybourn-Langton, L.; Monteiro, C.A.; Norman, I.; et al. Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2021, 40, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragavan, M.I.; Marcil, L.; Garg, A. Climate Change as a Social Determinant of Health. Pediatrics 2020, 145, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).