Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: Moderating Role of Green Brand Knowledge

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theory of Reasoned Action

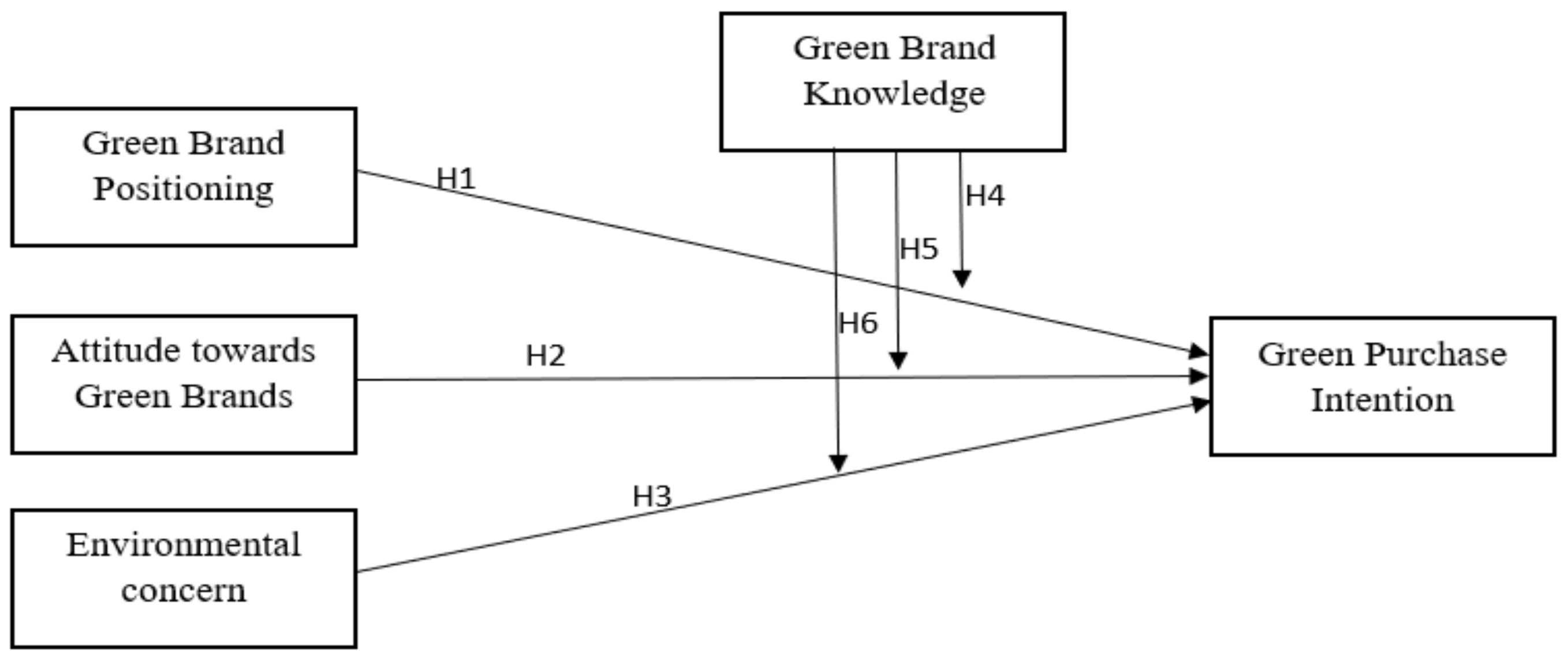

2.2. Green Brand Positioning and Green Purchase Intention

2.3. Attitude towards Green Brands and Green Purchase Intention

2.4. Environmental Concern and Green Purchase Intention

2.5. Moderating Effect of Green Brand Knowledge

2.6. Research Methodology

2.7. Questionnaire Development

3. Data Analysis and Results

3.1. Demographic Statistics

3.2. Measurement Model

3.3. Discriminant Validity

3.4. Common Method Variance, Variance Inflation Factor, R Square and F Square

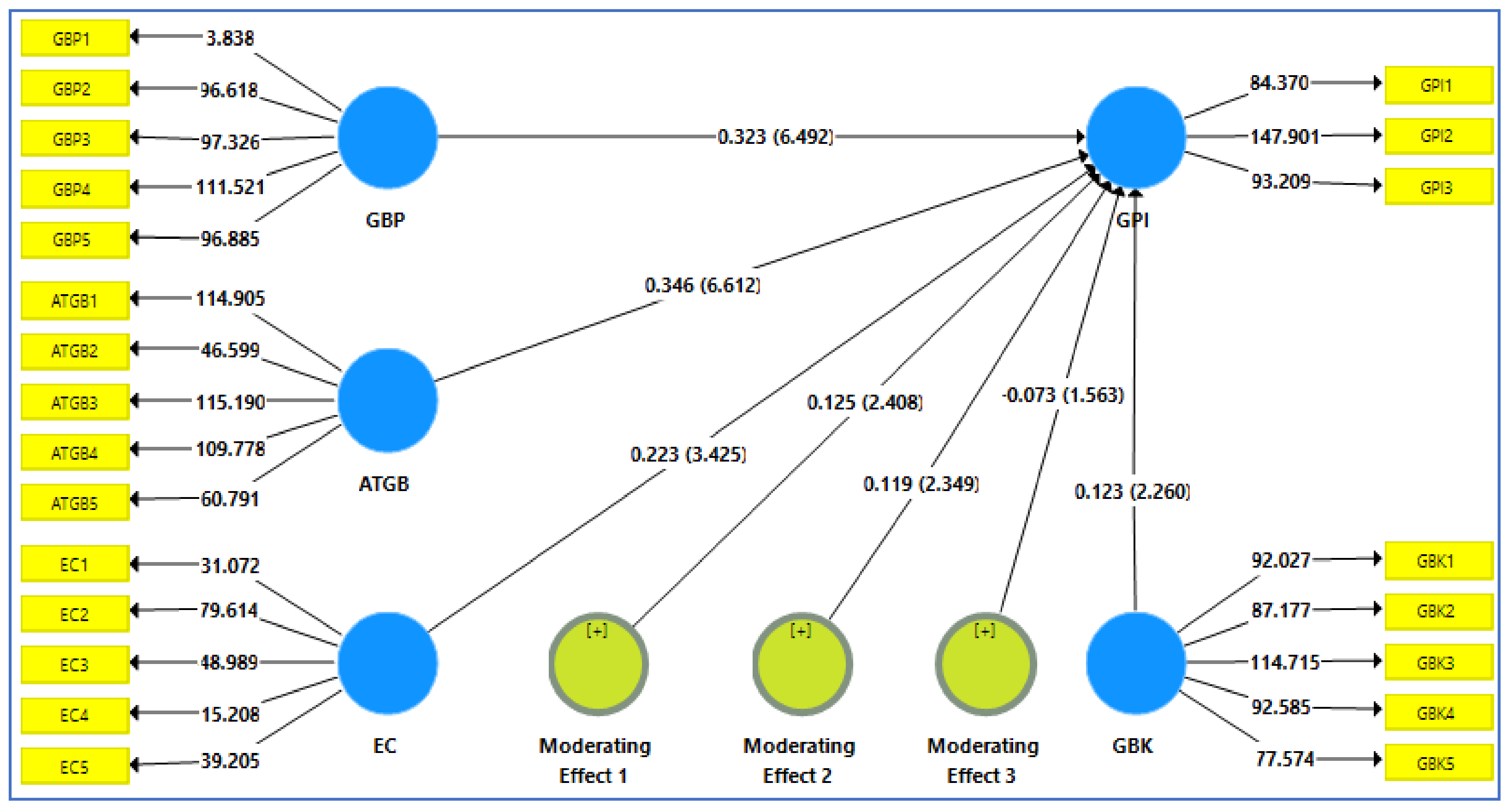

3.5. Structural Model

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Construct | Items |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Green Brand Positioning |

|

| 2 | Attitude toward green brand |

|

| 3 | Green brand knowledge |

|

| 4 | Environmental concern |

|

| 5 | Green products purchase intention |

|

References

- UN Sustainable Development Goals-Goal 13: Climate Action (2015, September); The United Nations: 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/ (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Sharples, J.J.; Cary, G.J.; Fox-Hughes, P.; Mooney, S.; Evans, J.P.; Fletcher, M.-S.; Fromm, M.; Grierson, P.F.; McRae, R.; Baker, P. Natural hazards in australia: Extreme bushfire. Clim. Chang. 2016, 139, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, M.W.; Ward-Fear, G.; L’Hotellier, F.; Herman, K.; Kabat, A.P.; Gibbons, J.P. Could biodiversity loss have increased australia’s bushfire threat? Anim. Conserv. 2016, 19, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, L.E.; Anderson, L.O.; Fonseca, M.G.; Rosan, T.M.; Vedovato, L.B.; Wagner, F.H.; Silva, C.V.; Junior, C.H.S.; Arai, E.; Aguiar, A.P. 21st century drought-related fires counteract the decline of amazon deforestation carbon emissions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.D.; Lee, S.H. Hybrid car purchase intentions: A cross-cultural analysis. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfred, A.M.; Adam, R.F. Green management matters regardless. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2009, 23, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelzlhammer, A. A Strategic Audit of Tesla; University of Nebraska–Lincoln: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J. Green marketing. Strateg. Dir. 2008, 24, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Ibanez, V.A. Green value added. Mark. Intel. Plan. 2006, 24, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norazah, M.S.; Norbayah, M.S. Consumers’ environmental behaviour towards staying at a green hotel: Moderation of green hotel knowledge. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2015, 26, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Soyez, K. How national cultural values affect pro-environmental consumer behavior. Int. Mark. Rev. 2012, 29, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ghodeswar, B.M. Factors affecting consumers’ green product purchase decisions. Mark. Intel. Plan. 2015, 33, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors affecting green purchase behaviour and future research directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, D.E.; Carreiro, M.M.; Cherrier, J.; Grulke, N.E.; Jennings, V.; Pincetl, S.; Pouyat, R.V.; Whitlow, T.H.; Zipperer, W.C. Coupling biogeochemical cycles in urban environments: Ecosystem services, green solutions, and misconceptions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Thinking green, buying green? Drivers of pro-environmental purchasing behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.; Pickett, G. How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. Determinants of industrial mail survey response: A survey-on-surveys analysis of researchers' and managers' views. J. Mark. Manag. 1996, 12, 505–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhead, B.; Karolchik, D.; Kuhn, R.M.; Hinrichs, A.S.; Zweig, A.S.; Fujita, P.A.; Diekhans, M.; Smith, K.E.; Rosenbloom, K.R.; Raney, B.J. The ucsc genome browser database: Update 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, D613–D619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naliwajek-Mazurek, K. Music and Torture in Nazi Sites of Persecution and Genocide in Occupied Poland, 1939–1945. World Music 2013, 2, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Brulet, A.; Davidson, P.; Keller, P.; Cotton, J. Observation of hairpin defects in a nematic main-chain polyester. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N.M. Green product purchase intention: Impact of green brands, attitude, and knowledge. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2893–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.-C. Effects of green brand on green purchase intention. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 250–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.A.; Sulaiman, Z.; Mas’od, A.; Muharam, F.M.; Tat, H.H. Effect of green brand positioning, knowledge, and attitude of customers on green purchase intention. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2019, 3, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Aulina, L.; Yuliati, E. The Effects of Green Brand Positioning, Green Brand Knowledge, and Attitude towards Green Brand on Green Products Purchase Intention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business and Management Research (ICBMR 2017), Padang, West Sumatra Province, Indonesia, 1–3 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.-J. Green brand positioning in the online environment. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Yusiana, R.; Widodo, A.; Hidayat, A.M.; Oktaviani, P.K. Green brand effects on green purchase intention (life restaurant never ended). Dinasti Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2020, 1, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, J.G.; Sarkar, A.; Yadav, R. Brand it green: Young consumers’ brand attitudes and purchase intentions toward green brand advertising appeals. Young Consum. 2019, 20, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, T.-W.; Li, H.-X.; Chen, Y.-R. The influence of green brand affect on green purchase intentions: The mediation effects of green brand associations and green brand attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VW, M.A.D. Green purchase intention: The impact of green brand cosmetics (green brand knowledge, attitude toward green brand, green brand equity). Manag. Sustain. Dev. J. 2020, 2, 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, T.K.; Kumar, A.; Jakhar, S.; Luthra, S.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kazancoglu, I.; Nayak, S.S. Social and environmental sustainability model on consumers’ altruism, green purchase intention, green brand loyalty and evangelism. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Naveed, R.T.; Ahmad, N.; Hamid, T.A. Predicting Green Brand Equity Through Green Brand Credibility. J. Manag. Sci. 2019, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Jaccard, J.; Davidson, A.R.; Ajzen, I.; Loken, B. Predicting and understanding family planning behaviors. In Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. A bayesian analysis of attribution processes. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhikun, D.; Fungfai, N. Knowledge sharing among architects in a project design team: An empirical test of theory of reasoned action in China. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2009, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, S.; Li, Y.; Crasquin-Soleau, S.; Feng, Q.; Mu, X.; Collin, P.-Y.; Reynolds, A.; Guo, L. Earliest triassic microbialites in the south china block and other areas: Controls on their growth and distribution. Facies 2007, 53, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Travel life cycle. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Han, H. Intention to pay conventional-hotel prices at a green hotel–a modification of the theory of planned behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Kang, J.H. Purchase intention of Chinese consumers toward a US apparel brand: A test of a composite behavior intention model. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: Forth Worth, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Bearden, W.O. A comparative analysis of two models of behavioral intention. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1992, 20, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Kao, C.C.; Bryant, G.O.; Liu, X.; Berk, A.J. Adenovirus e1a activation domain binds the basic repeat in the tata box transcription factor. Cell 1991, 67, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.-Y.; Choo, W.-C.; Doshi, S.; Lim, L.E.; Kua, E.-H. A community study of the health-related quality of life of schizophrenia and general practice outpatients in singapore. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2004, 39, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chai, J.C.; Hsu, P.; Lam, Y. Three-dimensional transient radiative transfer modeling using the finite-volume method. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2004, 86, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.G.; Spencer, S.J.; Quinn, D.M.; Gerhardstein, R. Consuming images: How television commercials that elicit stereotype threat can restrain women academically and professionally. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 1615–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.Y.; Janda, S. Predicting consumer intentions to purchase energy-efficient products. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdul-Wahid, M.S.; Verardi, R.; Veglia, G.; Prosser, R.S. Topology and immersion depth of an integral membrane protein by paramagnetic rates from dissolved oxygen. J. Biomol. NMR 2011, 51, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, P.; Shepherd, R. Self-identity and the theory of planned behavior: Assesing the role of identification with “green consumerism”. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, I.A.; Madden, S.L.; Rohwer-Nutter, P.; Bell, G.I.; Sukhatme, V.P.; Rauscher, F.J. Repression of the insulin-like growth factor ii gene by the wilms tumor suppressor wt1. Science 1992, 257, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. Determinants of corruption: A cross-national analysis. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2003, 11, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.A.; Lawi, N.H.B.M.; Muharam, F.M.; Kohar, U.H.A.; Choon, T.L.; Zakuan, N. Effects of Green Brand Positioning, Knowledge and Attitude on Green Product Purchase Intention. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Darnton, G. Green companies or green con-panies: Are companies really green, or are they pretending to be? Bus. Soc. Rev. 2005, 110, 117–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane Keller, K. Brand mantras: Rationale, criteria and examples. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwin, C.F.; Gwin, C.R. Product attributes model: A tool for evaluating brand positioning. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2003, 11, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, T.-W.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lai, P.-Y.; Wang, K.-H. The influence of proactive green innovation and reactive green innovation on green product development performance: The mediation role of green creativity. Sustainability 2016, 8, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Suki, N. Green products usage: Structural relationships on customer satisfaction and loyalty. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2017, 24, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Shades of green: A psychographic segmentation of the green consumer in kuwait using self-organizing maps. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 11030–11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, F.J.M.; Martinez, T.L.; Moreno, F.F.; Soriano, P.C. Improving attitudes toward brands with environmental associations: An experimental approach. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H. An intuitionistic fuzzy set–based hybrid approach to the innovative design evaluation mode for green products. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2016, 8, 1687814016642715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-c.A. Double standard: The role of environmental consciousness in green product usage. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, B.W.; Schroeder, F.C.; Jander, G. Identification of indole glucosinolate breakdown products with antifeedant effects on myzus persicae (green peach aphid). Plant. J. 2008, 54, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Quirk, R.G.; Shukla, S. Green Management for Sustainable Sugar Industry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers' intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.; Taylor, C.; Strick, S. Wine consumers’ environmental knowledge and attitudes: Influence on willingness to purchase. Int. J. Wine Res. 2009, 1, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezai, G.; Kit Teng, P.; Mohamed, Z.; Shamsudin, M.N. Consumer willingness to pay for green food in malaysia. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2013, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S. Sugarcane agriculture and sugar industry in india: At a glance. Sugar Tech. 2014, 16, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkanen, P.; Young, J.A. What determines British consumers’ motivation to buy sustainable seafood? Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1289–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ogden, D.T. To buy or not to buy? A social dilemma perspective on green buying. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 376–391. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.; Crittenden, V.; Felix, R.; Braunsberger, K. I believe therefore I care. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asih, D.; Setini, M.; Soelton, M.; Muna, N.; Putra, I.; Darma, D.; Judiarni, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 3367–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himawan, E. Pengaruh Green Brand Positioning, Green Brand Attitude, Green Brand Knowledge Terhadap Green Purchase Intention. J. Manaj. Bis. Kewirausahaan 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhuang, W.; Luo, X.; Riaz, M.U. On the factors influencing green purchase intention: A meta-analysis approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and pce. ACR N. Am. Adv. 2005, 17, 591–599. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Lim, S.-Y. Impact of environmental concern on image of internal gscm practices and consumer purchasing behavior. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situmorang, T.P.; Indriani, F.; Simatupang, R.A.; Soesanto, H. Brand positioning and repurchase intention: The effect of attitude toward green brand. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 491–499. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Fang, H.; Jacoby, G.; Li, G.; Wu, Z. Environmental regulations and innovation for sustainability? Moderating effect of political connections. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2021, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lu, Y.; Li, J.; Ni, J. Evaluating Environmentally Sustainable Development Based on the PSR Framework and Variable Weigh Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M.A. Green ergonomics: Challenges and opportunities. Ergonomics 2013, 56, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.-C. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate purchase intention of green products among thai consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainieri, T.; Barnett, E.G.; Valdero, T.R.; Unipan, J.B.; Oskamp, S. Green buying: The influence of environmental concern on consumer behavior. J. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 137, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, E.; Schultz, H. Production and quality aspects of rooibos tea and related products. A review. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2012, 80, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Consumers’ sustainable purchase behaviour: Modeling the impact of psychological factors. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Wang, M.; Sheng, S. Spatial evolution of URNCL and response of ecological security: A case study on Foshan City. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2017, 1, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Sheng, S.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, H.; Dong, J. Research on the construction of carbon emission evaluation system of low-carbon-oriented urban planning scheme: Taking the West New District of Jinan city as example. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2019, 3, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwitt, L.F.; Pitts, R.E. Predicting purchase intentions for an environmentally sensitive product. J. Consum. Psychol. 1996, 5, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, E.M.; Mais, E.L. Framing the “Green” alternative for environmentally conscious consumers. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2010, 1, 222–234. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, C.; Wee, H.Y.; Ozanne, L.; Kao, T. Consumers’ purchasing behavior towards green products in New Zealand. Innov. Mark. 2008, 4, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-S. The drivers of green brand equity: Green brand image, green satisfaction, and green trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Simintiras, A.C. The impact of green product lines on the environment: Does what they know affect how they feel? Mark. Intell. Plan. 1995, 13, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, A.A.; Fremeth, A. Strategic direction and management. Bus. Manag. Environ. Steward. Environ. Think. Prelude Manag. Action 2009, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, A.; Strutton, D. Marketing mix strategies for closing the gap between green consumers’ pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongplew, N.; van Koppen, C.K.; Spaargaren, G. Companies contributing to the greening of consumption: Findings from the dairy and appliance industries in thailand. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 75, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Li, B.; Larkin, D.M.; Lee, C.; Storz, J.F.; Antunes, A.; Greenwold, M.J.; Meredith, R.W. Comparative genomics reveals insights into avian genome evolution and adaptation. Science 2014, 346, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-C.; Huang, Y.-H. The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, U.C.; Ndubisi, N.O. Green buyer behavior: Evidence from asia consumers. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2013, 48, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Suki, N. Customer environmental satisfaction and loyalty in the consumption of green products. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2015, 22, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Paladino, A. Eating clean and green? Investigating consumer motivations towards the purchase of organic food. Australas. Mark. J. (AMJ) 2010, 18, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Predictors of young consumer’s green purchase behaviour. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2016, 27, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.K.; Yee, R.W.; Dai, J.; Lim, M.K. The moderating effect of environmental dynamism on green product innovation and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 181, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.; Bryman, A.; Ferguson, H. Understanding Research for Social Policy and Social Work 2E: Themes, Methods and Approaches; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, G.X.; Gao, X.; Tang, W.J.; Jie, X.Z.; Huang, X. Numerical study on transition structures of oblique detonations with expansion wave from finite-length cowl. Phys. Fluids 2020, 32, 56108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-C.; Kauffman, R.J.; Liang, T.-P. A growth theory perspective on b2c e-commerce growth in europe: An exploratory study. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2007, 6, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, S.; Xin, C.; Umrani, W.A.; Fatima, S.; Pal, D. How Do Leaders Influence Innovation and Creativity in Employees? The Mediating Role of Intrinsic Motivation. Adm. Soc. 2021, 53, 0095399721997427. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojiaku, O.; Achi, B.; Aghara, V. Cognitive-affective predictors of green purchase intentions among health workers in nigeria. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G.; Alvarado-Macancela, N.; Gavín-Quinchuela, T.; Carrión-Mero, P. Participatory socio-ecological system: Manglaralto-Santa Elena, Ecuador. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2018, 2, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. Pls-sem or cb-sem: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Bin Mohammad, H.; Nordin, S.B. Moderating effect of board characteristics in the relationship of structural capital and business performance: An evidence on pakistan textile sector. J. Stud. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 5, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: New Yok, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson College Division: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: New Yok, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito Vinzi, V.; Chin, W.W.; Henseler, J.; Wang, H. Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittino, D.; Martínez, A.B.; Chirico, F.; Galván, R.S. Psychological ownership, knowledge sharing and entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: The moderating role of governance heterogeneity. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.S.; Srivastava, S.C.; Jiang, L. Trust and electronic government success: An empirical study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2008, 25, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, C.M.; Brady, M.K.; Calantone, R.; Ramirez, E. Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using pls path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T. Considering common method variance in educational technology research. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in pls-sem: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. (IJeC) 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, M.C.; Becker, J.M.; Wende, S. Smart PLS 3; Smart PLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Macmillan: New Yok, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Bai, R.; Zhang, L. The unexpected effect of frugality on green purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.F.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Ringle, C.M.; Schlägel, C. A critical look at the use of SEM in international business research. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 376–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.-K.; Wu, W.-Y.; Pham, T.-T. Examining the moderating effects of green marketing and green psychological benefits on customers’ green attitude, value and purchase intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, G.K.; Kassar, A.-N.; Itani, O. The impact of environment concern and attitude on green purchasing behavior. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 230 | 58.1% |

| Male | 166 | 41.9% | |

| Age | 20–25 | 37 | 9.3% |

| 26–30 | 135 | 34.1% | |

| 31–40 | 134 | 33.8% | |

| 41 and above | 90 | 22.7% | |

| Marital status | Married | 272 | 68.7% |

| Single | 124 | 31.3% | |

| Education level | Diploma | 59 | 14.9% |

| Bachelors | 131 | 33.1% | |

| Masters | 172 | 43.4% | |

| Others | 34 | 8.6% | |

| Income per month | 15,000–25,000 | 103 | 26.0% |

| 26,000–35,000 | 165 | 41.7% | |

| 36,000–45,000 | 80 | 20.2% | |

| 46,000 and above | 48 | 12.1% | |

| Green shopping frequency | 1–2 times | 29 | 7.3% |

| 3–5 times | 118 | 29.8% | |

| 5–7 times | 153 | 38.6% | |

| 7–10 times | 96 | 24.2% |

| Construct Name | Items | Loading | C-Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBP | GBP1 GBP2 GBP3 GBP4 GBP5 | 0.652 0.904 0.913 0.914 0.907 | 0.912 | 0.936 | 0.747 |

| ATGB | ATGB1 ATGB2 ATGB3 ATGB4 ATGB5 | 0.924 0.857 0.916 0.923 0.874 | 0.941 | 0.955 | 0.809 |

| EC | EC1 EC2 EC3 EC4 EC5 | 0.825 0.883 0.86 0.675 0.821 | 0.875 | 0.908 | 0.666 |

| GBK | GBK1 GBK2 GBK3 GBK4 GBK5 | 0.919 0.894 0.911 0.908 0.892 | 0.945 | 0.958 | 0.819 |

| GPI | GPI1 GPI2 GPI3 | 0.895 0.940 0.905 | 0.901 | 0.938 | 0.835 |

| ATGB | EC | GBK | GBP | GPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATGB | 0.899 | ||||

| EC | 0.418 | 0.816 | |||

| GBK | 0.476 | 0.554 | 0.905 | ||

| GBP | 0.533 | 0.454 | 0.427 | 0.864 | |

| GPI | 0.583 | 0.487 | 0.477 | 0.618 | 0.914 |

| ATGB | EC | GBK | GBP | GPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATGB | |||||

| EC | 0.442 | ||||

| GBK | 0.502 | 0.589 | |||

| GBP | 0.569 | 0.495 | 0.457 | ||

| GPI | 0.628 | 0.524 | 0.513 | 0.676 |

| Criterion | Acceptability |

|---|---|

| Harman’s Single Factor Test | 31.472% variance proportion |

| VIF < 5 | GPI |

|---|---|

| GBK | 2.998 |

| GBP | 2.182 |

| ATGB | 1.877 |

| EC | 1.599 |

| R Square | |

|---|---|

| GPI | 0.506 |

| GPI | |

|---|---|

| GBP | 0.345 |

| ATGB | 0.049 |

| EC | 0.021 |

| Hypotheses | Relationship | Beta | STDEV | T Statistics | p-Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | GBP → GPI | 0.323 | 0.05 | 6.492 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | ATGB → GPI | 0.346 | 0.052 | 6.612 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | EC → GPI | 0.223 | 0.065 | 3.425 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Hypotheses | Relationship | Beta | STDEV | T Statistics | p-Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H4 | GBP × GBK -> GPI | −0.073 | 0.047 | 1.563 | 0.119 | Not Accepted |

| H5 | ATGB × GBK -> GPI | 0.125 | 0.052 | 2.408 | 0.016 | Accepted |

| H6 | EC × GBK -> GPI | 0.119 | 0.051 | 2.349 | 0.019 | Accepted |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siyal, S.; Ahmed, M.J.; Ahmad, R.; Khan, B.S.; Xin, C. Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: Moderating Role of Green Brand Knowledge. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010762

Siyal S, Ahmed MJ, Ahmad R, Khan BS, Xin C. Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: Moderating Role of Green Brand Knowledge. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(20):10762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010762

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiyal, Saeed, Munawar Javed Ahmed, Riaz Ahmad, Bushra Shahzad Khan, and Chunlin Xin. 2021. "Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: Moderating Role of Green Brand Knowledge" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 20: 10762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010762

APA StyleSiyal, S., Ahmed, M. J., Ahmad, R., Khan, B. S., & Xin, C. (2021). Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: Moderating Role of Green Brand Knowledge. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010762