Self-Efficacy Mediates Acculturation and Respite Care Knowledge of Immigrant Caregivers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Respite Care Knowledge

2.2. Acculturation and Self-Efficacy

2.3. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Respite Care Knowledge

3.2.2. Acculturation

3.2.3. Self-Efficacy

3.3. Statistical Analyses

4. Findings

4.1. Characteristics of Participants

4.2. Factors Associated with the Respite Care Knowledge

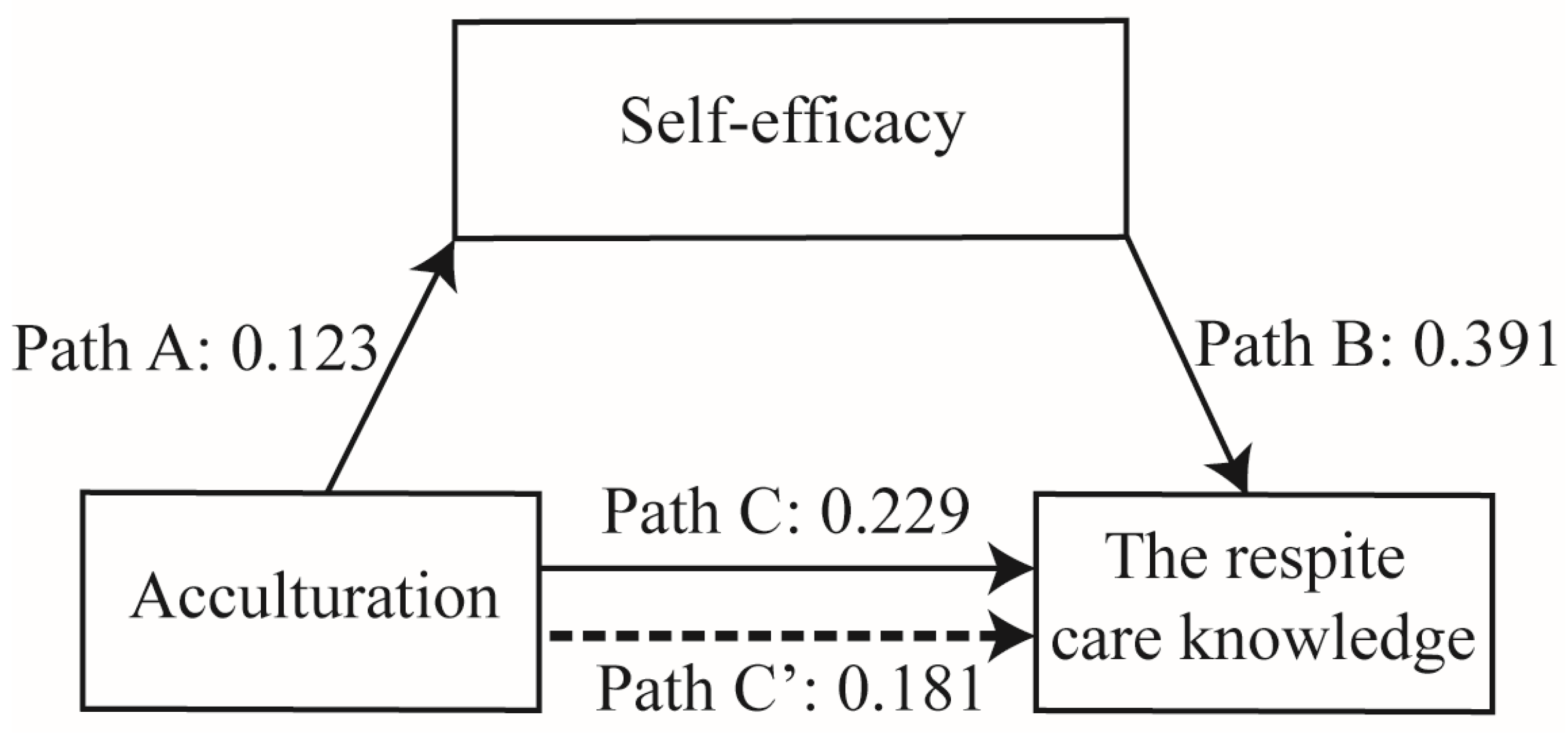

4.3. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Implications of Research Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Collins, R.N.; Kishita, N. Prevalence of depression and burden among informal care-givers of people with dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 2355–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ackerman, L.; Sheaffer, L. Effects of respite care training on respite provider knowledge and confidence, and outcomes for family caregivers receiving respite services. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2018, 37, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, G.; Knighting, K.; Bray, L.; Downing, J.; Jack, B.A.; Maden, M.; Mateus, C.; Noyes, J.; O’Brien, M.R.; Roe, B.; et al. The specification, acceptability and effectiveness of respite care and short breaks for young adults with complex healthcare needs: Protocol for a mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, B.; Hawkins, M.T.; Ostaszkiewicz, J.; Millar, L. Carers’ perspectives of respite care in Australia: An evaluative study. Contemp. Nurse A J. Aust. Nurs. Prof. 2012, 41, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Morgan, K.; Lindesay, J. Effect of Institutional Respite Care on the Sleep of People with Dementia and Their Primary Caregivers. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, E.J.; Tetley, J.; Clarke, A. Respite care for frail older people and their family carers: Concept analysis and user focus group findings of a pan-European nursing research project. J. Adv. Nurs. 1999, 30, 1396–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Ming, Y.; Chang, T.H.; Yen, Y.Y.; Lan, S.J. The Needs and Utilization of Long-Term Care Service Resources by Dementia Family Caregivers and the Affecting Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M. The Effect of Resources on Caregiving Experiences in the U.S. Population and among Korean American Caregivers; University of Maryland: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). World Migration Report 2020. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Whiting, C.G.; Heinz, P.A.; Prudencio, G.; Wittke, M.R.; Reinhard, S.; Feinberg, L.F.; Skufca, L.; Stephen, R.; Choula, R. Caregiving in the U.S. 2020. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2020/05/full-report-caregiving-in-the-united-states.doi.10.26419-2Fppi.00103.001.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Mathur, S.; Chandran, S.; Kishor, M.; Prakrithi, S.; Rao, T. A comparative study of caregiver burden and self-efficacy in chronic psychiatric illness and chronic medical illness: A pilot study. Arch. Ment. Health 2018, 19, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A.P.; Lee, J.; Palos, G.; Torres-Vigil, I. Cultural Influences in the Patterns of Long-Term Care Use Among Mexican American Family Caregivers. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2008, 27, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gagne, J.C.; Oh, J.; So, A.; Kim, S.S. The healthcare experiences of Koreans living in North Carolina: A mixed methods study. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F. Am I a daughter-in-law or a care worker? A study on the formation of the caretaking role and the caretaking experience of foreign daughters-in-law. NTU Soc. Work. Rev. 2012, 26, 139–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hardan-Khalil, K. Factors Affecting Health-Promoting Lifestyle Behaviors Among Arab American Women. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2019, 31, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikell, M.; Snethen, J.; Kelber, S.T. Exploring Factors Associated with Physical Activity in Latino Immigrants. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 42, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.D.; Caspi, C.; Yang, M.; Leyva, B.; Stoddard, A.M.; Tamers, S.; Tucker-Seeley, R.D.; Sorensen, G.C. Pathways between acculturation and health behaviors among residents of low-income housing: The mediating role of social and contextual factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 123, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barwise, A.; Cheville, A.; Wieland, M.L.; Gajic, O.; Greenberg-Worisek, A.J. Perceived knowledge of palliative care among immigrants to the United States: A secondary data analysis from the Health Information National Trends Survey. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2019, 8, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Sourtzi, P.; Bellali, T.; Theodorou, M.; Karamitri, L.; Siskou, O.; Charalambous, G.; Kaitelidou, D. Public health services knowledge and utilization among immigrants in Greece: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harris, M.; Diminic, S.; Marshall, C.; Stockings, E.; Degenhardt, L. Estimating service demand for respite care among informal carers of people with psychological disabilities in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seibel, V. Determinants of migrants’ knowledge about their healthcare rights. Health Sociol. Rev. 2019, 28, 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dastjerdi, M. The case of Iranian immigrants in the greater Toronto area: A qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2012, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44489 (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Davis, K.S.; Mohan, M.; Rayburn, S.W. Service quality and acculturation: Advancing immigrant healthcare utilization. J. Serv. Mark. 2017, 31, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation theory. In Encyclopedia of Management Theory; Kessler, E.H., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 4–8. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323445090_encyclopedia_of_managements_theory_encyclopedia_by_eric_hKessler_ed/link/5a9647880f7e9ba42972e52d/download (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Reissm, K.; Schunck, R.; Razum, O. Effect of Length of Stay on Smoking among Turkish and Eastern European Immigrants in Germany—Interpretation in the Light of the Smoking Epidemic Model and the Acculturation Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 15925–15936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahlan, R.; Badri, P.; Saltaji, H.; Amin, M. Impact of acculturation on oral health among immigrants and ethnic minorities: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jang, Y.; Rhee, M.-K.; Cho, Y.J.; Kim, M.T. Willingness to Use a Nursing Home in Asian Americans. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.R.; Mulvahill, M.J.; Tiwari, T. The Impact of Maternal Self-Efficacy and Oral Health Beliefs on Early Childhood Caries in Latino Children. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fang, C.Y.; Lee, M.; Feng, Z.; Tan, Y.; Levine, F.; Nguyen, C.; Ma, G.X. Community-Based Cervical Cancer Education: Changes in Knowledge and Beliefs Among Vietnamese American Women. J. Community Health 2019, 44, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenglass, E.; Schwarzer, R.; Jakubiec, S.D.; Fiksenbaum, L.; Taubert, S. The Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI): A multidimensional research instrument. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference of the Stress and Anxiety Research Society (STAR), Cracow, Poland, 12–14 July 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, N.J.; Bird, J.A.; Clark, M.A.; Rakowski, W.; Guerra, C.; Barker, J.C.; Pasick, R.J. Social and Cultural Meanings of Self-Efficacy. Health Educ. Behav. 2009, 36, 111s–128s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamimura, A.; Jess, A.; Trinh, H.N.; Aguilera, G.; Nourian, M.M.; Assasnik, N.; Ashby, J. Food Insecurity Associated with Self-Efficacy and Acculturation. Popul. Health Manag. 2016, 20, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Y. Examining the Impact of International Graduate Students’ Acculturation Experiences on Their Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy; The University of North Carolina at Greensboro: Greensboro, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, D.Y.; Leung, A.Y. Factor structure and gender invariance of the Chinese General Self-Efficacy Scale among soon-to-be-aged adults. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fu, T.S. Long-term care 2.0 initial resource deployment and service development. Public Gov. Q. 2019, 7, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Howse, K. Long-term Care Policy: The Difficulties of Taking a Global View. Ageing Horiz. 2007, 6, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson, L.; Johnson, K.; Cridland, E.; Hall, D.; Neville, C.; Fielding, E.; Hasan, H. Knowledge, help-seeking and efficacy to find respite services: An exploratory study in help-seeking carers of people with dementia in the context of aged care reforms. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschenbacher, S. Transformative learning theory and migration. Having transformative and edifying conversations. Eur. J. Res. Educ. Learn. Adults 2020, 11, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimane, T.A.; Downing, C. Transformative learning in nursing education: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 7, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuki, N.; Fukui, S.; Sakaguchi, Y. Measuring the Benefits of Respite Care use by Children with Disabilities and Their Families. J. Pediatric Nurs. 2020, 53, E14–E20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravdal Kvarme, L.; Albertini-Fruh, E.; Brekke, I.; Gardsjord, R.; Halvorsrud, L.; Liden, H. On duty all the time: Health and quality of life among immigrant parents caring for a child with complex health needs. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variable | n (%)/Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Nationality | |

| Vietnam | 68 (50.7) |

| China | 28 (20.9) |

| Indonesia | 22 (16.4) |

| Thailand | 4 (3.0) |

| The Philippines | 9 (6.7) |

| Other | 3 (2.2) |

| Age (years) | 39.05 (8.9) |

| Length of stay in Taiwan (Years) | 12.6 (8.6) |

| Education received in home country | |

| Illiterate or elementary school | 20 (14.9) |

| Junior high school | 36 (26.9) |

| Senior high school | 50 (37.3) |

| University or higher | 28 (20.9) |

| Education received in Taiwan | |

| Illiterate | 69 (51.5) |

| Elementary school | 38 (28.4) |

| Junior high school | 15 (11.2) |

| Senior high school | 6 (4.5) |

| University or higher | 6 (4.5) |

| Language ability | |

| Speaking Taiwanese only | 5 (3.7) |

| Speaking Chinese only | 75 (56) |

| Speaking and writing Chinese | 54 (40.3) |

| Citizenship identity | |

| Resident permit | 51 (38.1) |

| Permanent residence permit | 6 (4.5) |

| Citizen | 77 (57.5) |

| Family structure | |

| Nuclear family | 66 (49.3) |

| Eclectic family | 55 (41.0) |

| Extended family | 13 (9.7) |

| Monthly income a | |

| <NT$30,000 | 88 (65.7) |

| NT$30,001~50,000 | 28 (20.9) |

| ≥NT$50,001 | 18 (13.4) |

| Living environment | |

| Urban (including industrial areas) | 87 (64.9) |

| Rural countryside (including fishing villages) | 47 (35.1) |

| Sources of information on LTC services | 1.84 (1.13) |

| Acculturation | 2.70 (1.10) |

| Self-efficacy | 2.51 (0.66) |

| Respite care knowledge | 2.61 (1.01) |

| Variable | Respite Care Knowledge | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | F (p)/t (p)/r(p) b | |

| Nationality | 0.927 (0.466) | |

| Vietnam | 2.56 (1.05) | |

| China | 2.45 (0.97) | |

| Indonesia | 2.63 (1.00) | |

| Thailand | 2.90 (0.95) | |

| The Philippines | 3.20 (0.81) | |

| Other | 3.00 (1.00) | |

| Age (years) | 0.292 (0.001) ** | |

| Education received in home country | 2.237 (0.087) | |

| Illiterate or elementary school | 2.54 (0.84) | |

| Junior high school | 2.64 (1.12) | |

| Senior high school | 2.40 (1.01) | |

| University or higher | 3.00 (0.86) | |

| Education received in Taiwan | 1.658 (0.164) | |

| Illiterate | 2.64 (1.00) | |

| Elementary school | 2.46 (1.00) | |

| Junior high school | 3.09 (1.10) | |

| Senior high school | 2.00 (0.59) | |

| University or higher | 2.66 (0.94) | |

| Citizenship identity | 1.606 (0.205) | |

| Resident permit | 2.46 (1.04) | |

| Permanent residence permit | 2.23 (1.02) | |

| Citizen | 2.74 (0.97) | |

| Family structure | 0.061 (0.940) | |

| Nuclear family | 2.59 (1.08) | |

| Eclectic family | 2.65 (0.91) | |

| Extended family | 2.56 (1.10) | |

| Monthly income a | 0.150 (0.861) | |

| <NT$30,000 | 2.58 (1.06) | |

| NT$30,001~50,000 | 2.70 (1.02) | |

| ≥NT$50,001 | 2.61 (0.66) | |

| Living environment | 0.094 (0.925) | |

| Urban (including industrial areas) | 2.62 (1.07) | |

| Rural countryside (including fishing villages) | 2.60 (0.89) | |

| Sources of information on LTC services | 0.220 (0.008) ** | |

| Acculturation | 0.351 (<0.001) *** | |

| Self-efficacy | 0.286 (0.001) ** |

| Effect | Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | B | SE | t | p Value | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect (path C) | X | Y | 0.229 | 0.084 | 2.728 | 0.007 | 0.063–0.394 |

| Indirect effect (path A) | X | M | 0.123 | 0.049 | 2.398 | 0.018 | 0.022–0.224 |

| Indirect effect (path B) | M | Y | 0.391 | 0.121 | 2.033 | 0.002 | 0.152–0.630 |

| Direct effect (path C’) | X | Y | 0.181 | 0.084 | 2.161 | 0.033 | 0.015–0.346 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuo, S.-F.; Chen, I.-H.; Huang, T.-W.; Miao, N.-F.; Peters, K.; Chung, M.-H. Self-Efficacy Mediates Acculturation and Respite Care Knowledge of Immigrant Caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010595

Kuo S-F, Chen I-H, Huang T-W, Miao N-F, Peters K, Chung M-H. Self-Efficacy Mediates Acculturation and Respite Care Knowledge of Immigrant Caregivers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(20):10595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010595

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuo, Shu-Fen, I-Hui Chen, Tsai-Wei Huang, Nae-Fang Miao, Kath Peters, and Min-Huey Chung. 2021. "Self-Efficacy Mediates Acculturation and Respite Care Knowledge of Immigrant Caregivers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 20: 10595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010595

APA StyleKuo, S.-F., Chen, I.-H., Huang, T.-W., Miao, N.-F., Peters, K., & Chung, M.-H. (2021). Self-Efficacy Mediates Acculturation and Respite Care Knowledge of Immigrant Caregivers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010595