Psychological Distress and Post-Traumatic Symptomatology among Dental Healthcare Workers in Russia: Results of a Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

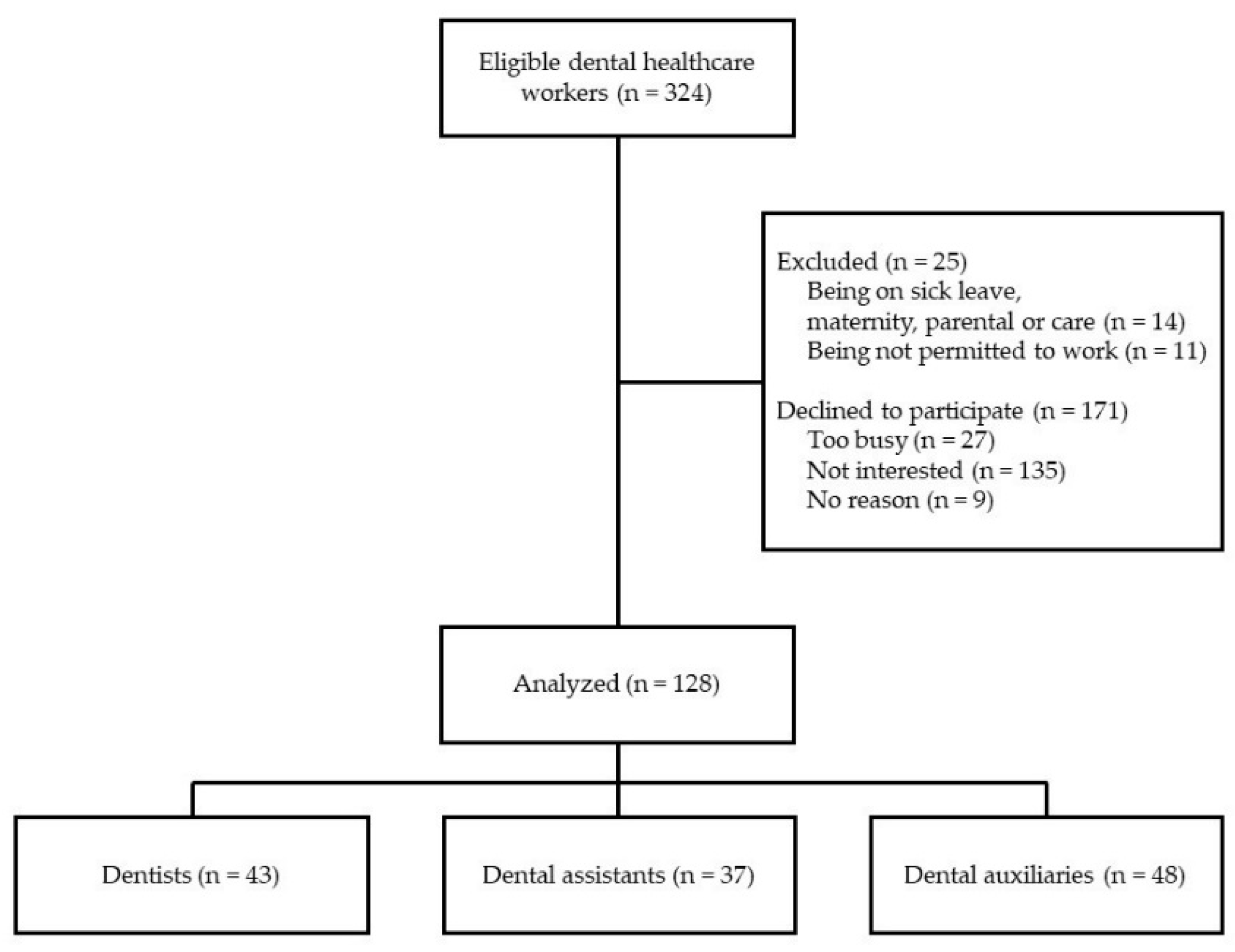

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethics Approval

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Prevalence of Psychological Distress and PTSD in Healthcare Workers

3.3. Risk Factors for PTSD Symptoms Development

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Meng, S.; Shi, J.; Lu, L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: Address mental health care to empower society. Lancet 2020, 395, e37–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braquehais, M.D.; Vargas-Cáceres, S.; Gómez-Durán, E.; Nieva, G.; Valero, S.; Casas, M.; Bruguera, E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals. Qjm Int. J. Med. 2020, 113, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, T.; Harju-Seppänen, J.; Adeniji, M.; Steel, C.; Grey, N.; Brewin, C.R.; Bloomfield, M.A.; Billings, J. Predictors and rates of PTSD, depression and anxiety in UK frontline health and social care workers during COVID-19. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra-Hebert, A.D.; Jehi, L.; Ji, X.; Nowacki, A.S.; Gordon, S.; Terpeluk, P.; Chung, M.K.; Mehra, R.; Dell, K.M.; Pennell, N.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Workers’ Risk of Infection and Outcomes in a Large, Integrated Health System. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 3293–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riello, M.; Purgato, M.; Bove, C.; MacTaggart, D.; Rusconi, E. Prevalence of post-traumatic symptomatology and anxiety among residential nursing and care home workers following the first COVID-19 outbreak in Northern Italy. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghera, J.; Pattani, N.; Hashmi, Y.; Varley, K.F.; Cheruvu, M.S.; Bradley, A.; Burke, J. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the mental health of healthcare workers in a hospital setting—A Systematic Review. J. Occup. Health 2020, 62, e12175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Yang, C.; Cai, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, B.; Tang, S.; Bai, H.; Guo, X.; Wu, J.; et al. Acute psychological effects of Coronavirus Disease 2019 outbreak among healthcare workers in China: A cross-sectional study. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, H.; Malpas, C.B.; Burrell, A.J.; Gurvich, C.; Chen, L.; Kulkarni, J.; Winton-Brown, T. Burnout and psychological distress amongst Australian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Australas. Psychiatry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechter, A.; Diaz, F.; Moise, N.; Anstey, D.E.; Ye, S.; Agarwal, S.; Birk, J.L.; Brodie, D.; Cannone, D.E.; Chang, B.; et al. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Hua, F.; Bian, Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and Future Challenges for Dental and Oral Medicine. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparro, R.; Scandurra, C.; Maldonato, N.; Dolce, P.; Bochicchio, V.; Valletta, A.; Sammartino, G.; Sammartino, P.; Mariniello, M.; Di Lauro, A.; et al. Perceived Job Insecurity and Depressive Symptoms Among Italian Dentists: The Moderating Role of Fear of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tysiąc-Miśta, M.; Dziedzic, A. The Attitudes and Professional Approaches of Dental Practitioners during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Buenaventura, A.; Chavez-Tuñon, M.; Castro-Ruiz, C. The Mental Health Consequences of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic in Dentistry. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarapultseva, M.; Hu, D.; Sarapultsev, A. SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity among dental staff and the role of aspirating systems. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2021. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; Jing, P.; Zhan, P.; Fang, Y.; Wang, F. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in healthcare workers after the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak: A survey of a large tertiary care hospital in Wuhan. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 294, 113541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Wang, Y.; Rauch, A.; Wei, F. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-R.; Wang, K.; Yin, L.; Zhao, W.-F.; Xue, Q.; Peng, M.; Min, B.-Q.; Tian, Q.; Leng, H.-X.; Du, J.-L.; et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 89, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijiritsky, E.; Hamama-Raz, Y.; Liu, F.; Datarkar, A.; Mangani, L.; Caplan, J.; Shacham, A.; Kolerman, R.; Mijiritsky, O.; Ben-Ezra, M.; et al. Subjective Overload and Psychological Distress among Dentists during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, N.; Aly, N.M.; Folayan, M.O.; Khader, Y.; Virtanen, J.I.; Al-Batayneh, O.B.; Mohebbi, S.Z.; Attia, S.; Howaldt, H.-P.; Boettger, S.; et al. Behavior change due to COVID-19 among dental academics—The theory of planned behavior: Stresses, worries, training, and pandemic severity. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.K.R.; Chellaswamy, K.S.; Kattula, D.; Thavarajah, R.; Mohandoss, A.A. Perceived stress and psychological distress among indian endodontists during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakami, Z.; Khanagar, S.B.; Vishwanathaiah, S.; Hakami, A.; Bokhari, A.M.; Jabali, A.H.; Alasmari, D.; AlDrees, A.M. Psychological impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on dental students: A nationwide study. J. Dent. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consolo, U.; Bellini, P.; Bencivenni, D.; Iani, C.; Checchi, V. Epidemiological Aspects and Psychological Reactions to COVID-19 of Dental Practitioners in the Northern Italy Districts of Modena and Reggio Emilia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shacham, M.; Hamama-Raz, Y.; Kolerman, R.; Mijiritsky, O.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Mijiritsky, E. COVID-19 Factors and Psychological Factors Associated with Elevated Psychological Distress among Dentists and Dental Hygienists in Israel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Jouhar, R.; Ahmed, N.; Adnan, S.; Aftab, M.; Zafar, M.S.; Khurshid, Z. Fear and Practice Modifications among Dentists to Combat Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal State Statistics Service. Available online: https://rosstat.gov.ru/folder/13721 (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Brooks, S.K.; Dunn, R.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.J.; Greenberg, N. A Systematic, Thematic Review of Social and Occupational Factors Associated with Psychological Outcomes in Healthcare Employees During an Infectious Disease Outbreak. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dordi, M.D.; Jethmalani, K.; Kumar, M.K. The Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Indian Health Care Workers. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, M.; Goh, E.T.; Tan, B.; Kanneganti, A.; Almonte, M.; Scott, A.; Martin, G.; Clarke, J.; Sounderajah, V.; Markar, S.; et al. Determinants of burnout and other aspects of psychological well-being in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multinational cross-sectional study. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.O.M. Psychological impact of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on health care workers in a medium size regional general hospital in Singapore. Occup. Med. 2004, 54, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Chatterjee, S.S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Gupta, S.; Das, S.; Banerjee, B.B. Attitude, practice, behavior, and mental health impact of COVID-19 on doctors. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, N.W.; Lee, G.K.; Tan, B.Y.; Jing, M.; Goh, Y.; Ngiam, N.J.; Yeo, L.L.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, F.A.; Shanmugam, G.N.; et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.Y.; Chew, N.W.; Lee, G.K.; Jing, M.; Goh, Y.; Yeo, L.L.; Zhang, K.; Chin, H.-K.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, F.A.; et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; Ma, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Yao, L.; Bai, H.; Cai, Z.; Yang, B.X.; et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffey, S.F.; Gudmundsdottir, B.; Beck, J.G.; Palyo, S.A.; Miller, L.; Beck, G. Screening for PTSD in motor vehicle accident survivors using the PSS-SR and IES. J. Trauma. Stress 2006, 19, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.D.; Tran, T.; Fisher, J. Validation of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) 21 as a screening instrument for depression and anxiety in a rural community-based cohort of northern Vietnamese women. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotareva, A.A. Systematic Review of the Psychometric Properties of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21). Bekhterev. Rev. Psychiatry Med. Psychol. 2020, 2, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.S. The Impact of Event Scale: Revised. In Cross-Cultural Assessment of Psychological Trauma and PTSD; Wilson, J.P., Tang, C.S., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, D.S. The Impact of Event Scale: Revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD, 2nd ed.; Wilson, J.P., Keane, T.E., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 339–411. [Google Scholar]

- Tarabrina, N.V. Workshop on the Psychology of Post-Traumatic Stress; Piter: Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2001; pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E.B.; Cashman, L.; Jaycox, L.; Perry, K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychol. Assess. 1997, 9, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollifield, M.; Hewage, C.; Gunawardena, C.N.; Kodituwakku, P.; Bopagoda, K.; Weerarathnege, K. International Post-Tsunami Study Group Symptoms and coping in Sri Lanka 20–21 months after the 2004 tsunami. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 192, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Foghi, C.; Dell’Oste, V.; Cordone, A.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Bui, E.; Dell’Osso, L. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: What can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sahoo, S. Pandemic and mental health of the front-line healthcare workers: A review and implications in the Indian context amidst COVID-19. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, M.Y.; Kasyanov, E.D.; Rukavishnikov, G.V.; Makarevich, O.V.; Neznanov, N.G.; Morozov, P.V.; Lutova, N.B.; Mazo, G.E. Stress and stigmatization in health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.Y.; Tam, W.; Lu, Y.; Ho, C.S.; Zhang, M.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of Depression in the Community from 30 Countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadkova, I.V. Features of prepension age persons’ employment. Hum. Prog. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareket-Bojmel, L.; Shahar, G.; Margalit, M. COVID-19-Related Economic Anxiety Is as High as Health Anxiety: Findings from the USA, the UK, and Israel. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ochoa, S.A.; Franco, O.H.; Rojas, L.Z.; Raguindin, P.F.; Roa-Díaz, Z.M.; Wyssmann, B.M.; Guevara, S.L.R.; Echeverría, L.E.; Glisic, M.; Muka, T. COVID-19 in Healthcare Workers: A Living Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prevalence, Risk Factors, Clinical Characteristics, and Outcomes. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.M.; Groenewold, M.R.; Lessem, S.E.; Xu, K.; Ussery, E.N.; Wiegand, R.E.; Qin, X.; Do, T.; Thomas, D.; Tsai, S.; et al. Update: Characteristics of Health Care Personnel with COVID-19—United States, February 12–July 16, 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1364–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, C.; Fontanesi, L.; Lanzara, R.; Rosa, I.; Porcelli, P. Fragile heroes. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health-care workers in Italy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, S.M.; Bealey, R.; Birch, J.; Cushing, T.; Parke, S.; Sergi, G.; Bloomfield, M.; Meiser-Stedman, R. The prevalence of common and stress-related mental health disorders in healthcare workers based in pandemic-affected hospitals: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2020, 11, 1810903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Sun, N.; Xu, J.; Geng, S.; Li, Y. Study of the mental health status of medical personnel dealing with new coronavirus pneumonia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerster, K.D.; Campbell, S.; Dolan, M.; Stappenbeck, C.A.; Yard, S.; Simpson, T.; Nelson, K.M. PTSD is associated with poor health behavior and greater Body Mass Index through depression, increasing cardiovascular disease and diabetes risk among U.S. veterans. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 15, 100930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 27 (21.1) |

| Female | 101 (78.9) |

| Age | |

| 21–35 years | 54 (42.2) |

| 36–50 years | 54 (42.2) |

| 51–64 years | 20 (15.6) |

| Working position | |

| Direct | 80 (62.5) |

| Indirect | 48 (37.5) |

| Occupation | |

| Dentists | 43 (33.6) |

| Dental Assistants | 37 (28.9) |

| Dental auxiliaries | 48 (37.5) |

| Category | Total | Sex | Age | Working Position | Occupation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | 21–35 Years | 36–50 Years | 51–64 Years | Dir. | Indir. | Dent. | Dent. ass. | Dent. auxil. | ||

| Prevalence, % | |||||||||||

| DASS-21 dep. | |||||||||||

| normal | 79.69 | 81.48 | 79.21 | 85.19 | 87.04 | 45.00 | 80.00 | 79.17 | 79.07 | 81.08 | 79.17 |

| mild | 11.72 | 11.11 | 11.88 | 9.26 | 9.26 | 25.00 | 10.00 | 14.58 | 9.30 | 10.81 | 14.58 |

| moderate | 6.25 | 3.70 | 6.93 | 3.70 | 0 | 30.00 | 8.75 | 2.08 | 9.30 | 8.11 | 2.08 |

| severe | 1.56 | 3.70 | 0.99 | 1.85 | 1.85 | 0 | 1.25 | 2.08 | 2.33 | 0 | 2.08 |

| extreme severe | 0.78 | 0 | 0.99 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 | 0 | 2.08 | 0 | 0 | 2.08 |

| DASS-21 anx. | |||||||||||

| normal | 75.78 | 66.67 | 78.22 | 81.48 | 74.07 | 65.00 | 78.75 | 70.83 | 79.07 | 78.38 | 70.83 |

| mild | 14.84 | 22.22 | 12.87 | 11.11 | 14.81 | 25.00 | 12.50 | 18.75 | 9.30 | 16.22 | 18.75 |

| moderate | 3.91 | 7.41 | 2.97 | 1.85 | 5.56 | 5.00 | 3.75 | 4.17 | 4.65 | 2.70 | 4.17 |

| severe | 3.12 | 3.70 | 2.97 | 5.56 | 1.85 | 0 | 2.50 | 4.17 | 2.33 | 2.70 | 4.17 |

| extreme severe | 2.34 | 0 | 2.97 | 0 | 3.70 | 5.00 | 2.50 | 2.08 | 4.65 | 0 | 2.08 |

| DASS-21 str. | |||||||||||

| normal | 75.78 | 70.37 | 77.23 | 81.48 | 79.63 | 50.00 | 76.25 | 75.00 | 69.77 | 83.78 | 75.00 |

| mild | 11.72 | 14.81 | 10.89 | 3.70 | 16.67 | 20.00 | 10.00 | 14.58 | 16.28 | 2.70 | 14.58 |

| moderate | 7.81 | 11.11 | 6.93 | 14.81 | 0 | 10.00 | 7.50 | 8.33 | 4.65 | 10.81 | 8.33 |

| severe | 3.91 | 3.70 | 3.96 | 0 | 1.85 | 20.00 | 6.25 | 0 | 9.30 | 2.70 | 0 |

| extreme severe | 0.78 | 0 | 0.99 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 | 0 | 2.08 | 0 | 0 | 2.08 |

| PSS-SR tot. | |||||||||||

| mild | 70.31 | 70.37 | 70.30 | 74.07 | 74.07 | 50.00 | 65.00 | 79.17 | 58.14 | 72.97 | 79.17 |

| moderate | 22.66 | 22.22 | 22.77 | 18.52 | 25.93 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 18.75 | 30.23 | 18.92 | 18.75 |

| severe | 7.03 | 7.41 | 6.93 | 7.41 | 0 | 25 | 10.00 | 2.08 | 11.63 | 8.11 | 2.08 |

| IES-R tot. | |||||||||||

| normal | 92.97 | 96.30 | 92.08 | 100 | 90.74 | 80.00 | 92.50 | 93.75 | 90.70 | 94.59 | 93.75 |

| mild | 3.91 | 0 | 4.95 | 0 | 5.56 | 10.00 | 2.50 | 6.25 | 4.65 | 0 | 6.25 |

| moderate | 1.56 | 3.70 | 0.99 | 0 | 3.70 | 0 | 2.50 | 0 | 2.33 | 2.70 | 0 |

| severe | 1.56 | 0 | 1.98 | 0 | 0 | 10.00 | 2.5 | 0 | 2.33 | 2.70 | 0 |

| Category | Total | Sex | Age | Working Position | Occupation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | 21–35 Years | 36–50 Years | 51–64 Years | Dir. | Indir. | Dent. | Dent. ass. | Dental auxil. | ||

| Mean (SD) DASS-21, PSS-SR, and IES-R Scores | |||||||||||

| DASS-21 dep. | 2.63 | 2.96 | 2.55 | 2.11 | 2.41 | 4.65 | 2.56 | 2.75 | 2.77 | 2.32 | 2.75 |

| SD | 2.98 | 2.86 | 3.02 | 2.70 | 2.81 | 3.44 | 2.83 | 3.25 | 3.02 | 2.61 | 3.25 |

| DASS-21 anx. | 2.23 | 2.41 | 2.19 | 1.59 | 2.52 | 3.20 | 2.09 | 2.48 | 2.33 | 1.81 | 2.48 |

| SD | 2.66 | 2.36 | 2.74 | 2.25 | 2.85 | 2.84 | 2.68 | 2.63 | 3.10 | 2.11 | 2.63 |

| DASS-21 stress | 4.48 | 4.7 | 4.40 | 3.76 | 4.26 | 7.00 | 4.61 | 4.25 | 5.33 | 3.78 | 4.25 |

| SD | 4.06 | 4.30 | 4.01 | 3.78 | 3.78 | 4.69 | 4.05 | 4.11 | 4.32 | 3.58 | 4.11 |

| DASS-21 total | 9.34 | 10.15 | 9.13 | 7.46 | 9.19 | 14.8 | 9.26 | 9.48 | 10.4 | 7.92 | 9.48 |

| SD | 8.88 | 8.21 | 9.08 | 8.14 | 8.72 | 9.38 | 8.71 | 9.25 | 9.45 | 7.67 | 9.25 |

| PSS-SR re-exp. | 1.7 | 1.33 | 1.88 | 1.52 | 1.59 | 2.90 | 2.13 | 1.17 | 2.23 | 2.00 | 1.17 |

| SD | 2.14 | 1.39 | 2.29 | 2.01 | 1.90 | 2.77 | 2.38 | 1.51 | 2.39 | 2.39 | 1.51 |

| PSS-SR avoid. | 2.6 | 2.41 | 2.75 | 2.57 | 2.19 | 4.30 | 3.01 | 2.13 | 3.16 | 2.84 | 2.13 |

| SD | 3.11 | 3.21 | 3.10 | 3.40 | 2.08 | 4.13 | 3.32 | 2.69 | 3.36 | 3.30 | 2.69 |

| PSS-SR arousal | 2.7 | 2.89 | 2.73 | 2.26 | 2.69 | 4.35 | 3.08 | 2.25 | 3.56 | 2.51 | 2.25 |

| SD | 2.53 | 2.75 | 2.48 | 2.30 | 2.18 | 3.38 | 2.70 | 2.14 | 2.88 | 2.40 | 2.14 |

| PSS-SR total | 7.2 | 6.63 | 7.37 | 6.35 | 6.46 | 11.5 | 8.21 | 5.54 | 8.95 | 7.35 | 5.54 |

| SD | 6.88 | 6.49 | 2.48 | 6.61 | 5.35 | 9.53 | 7.38 | 5.64 | 7.72 | 7.00 | 5.64 |

| IES-R intrus. | 2.4 | 1.89 | 2.55 | 1.57 | 2.63 | 4.10 | 2.85 | 1.69 | 3.09 | 2.57 | 1.69 |

| SD | 3.41 | 2.71 | 3.57 | 2.63 | 3.54 | 5.04 | 3.59 | 2.98 | 3.87 | 3.25 | 2.98 |

| IES-R avoid. | 3.1 | 2.44 | 3.29 | 2.35 | 2.94 | 5.60 | 3.68 | 2.17 | 3.60 | 3.76 | 2.17 |

| SD | 3.92 | 3.51 | 4.02 | 3.05 | 3.91 | 5.06 | 4.18 | 3.25 | 4.34 | 4.05 | 3.25 |

| IES-R hyperar. | 2.0 | 2.37 | 1.99 | 1.59 | 1.91 | 3.80 | 2.29 | 1.71 | 2.49 | 2.05 | 1.71 |

| SD | 2.74 | 2.47 | 2.82 | 2.13 | 2.51 | 4.02 | 3.04 | 2.14 | 3.27 | 2.78 | 2.14 |

| IES-R total | 7.5 | 6.70 | 7.83 | 5.52 | 7.48 | 13.5 | 8.81 | 5.56 | 9.19 | 8.38 | 5.56 |

| SD | 9.32 | 8.02 | 9.65 | 6.20 | 9.41 | 13.28 | 10.04 | 7.63 | 10.81 | 9.19 | 7.63 |

| Model | Β | 95%CI | SE | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1. Predictors of PTSD Symptoms (PSS-SR) | ||||||

| Sex | 0.37 | −1.64 to 2.39 | 1.02 | 0.05 | 0.37 | >0.05 |

| Working position | 2.54 | 0.82 to 4.26 | 0.87 | 0.37 | 1.31 | <0.01 |

| Age | 0.01 | −0.07 to 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.13 | >0.05 |

| Depression | 0.49 | −0.03 to 1.00 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 1.87 | >0.05 |

| Anxiety | 0.39 | −0.07 to 0.85 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 1.68 | >0.05 |

| Stress | 0.76 | 0.42 to 1.10 | 0.17 | 0.45 | 4.34 | <0.001 |

| Model 2. Predictors of PTSD Symptoms (IES-R) | ||||||

| Sex | 0.66 | −2.46 to 3.77 | 1.57 | 0.07 | 0.31 | >0.05 |

| Working position | 2.87 | 0.22 to 5.53 | 1.34 | 0.31 | 1.59 | <0.05 |

| Age | 0.06 | −0.07 to 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.86 | >0.05 |

| Depression | 0.47 | −0.32 to 1.27 | 0.40 | 0.15 | 1.10 | >0.05 |

| Anxiety | 0.40 | −0.31 to 1.11 | 0.36 | 0.11 | 1.12 | >0.05 |

| Stress | 1.00 | 0.48 to 1.52 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 3.83 | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarapultseva, M.; Zolotareva, A.; Kritsky, I.; Nasretdinova, N.; Sarapultsev, A. Psychological Distress and Post-Traumatic Symptomatology among Dental Healthcare Workers in Russia: Results of a Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020708

Sarapultseva M, Zolotareva A, Kritsky I, Nasretdinova N, Sarapultsev A. Psychological Distress and Post-Traumatic Symptomatology among Dental Healthcare Workers in Russia: Results of a Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):708. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020708

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarapultseva, Maria, Alena Zolotareva, Igor Kritsky, Natal’ya Nasretdinova, and Alexey Sarapultsev. 2021. "Psychological Distress and Post-Traumatic Symptomatology among Dental Healthcare Workers in Russia: Results of a Pilot Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020708

APA StyleSarapultseva, M., Zolotareva, A., Kritsky, I., Nasretdinova, N., & Sarapultsev, A. (2021). Psychological Distress and Post-Traumatic Symptomatology among Dental Healthcare Workers in Russia: Results of a Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 708. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020708