Rise of ‘Lonely’ Consumers in the Post-COVID-19 Era: A Synthesised Review on Psychological, Commercial and Social Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Data Mapping

2.2. Data Refinement

2.3. Data Evaluation

2.3.1. Inductive Analysis: Identification of Key Themes

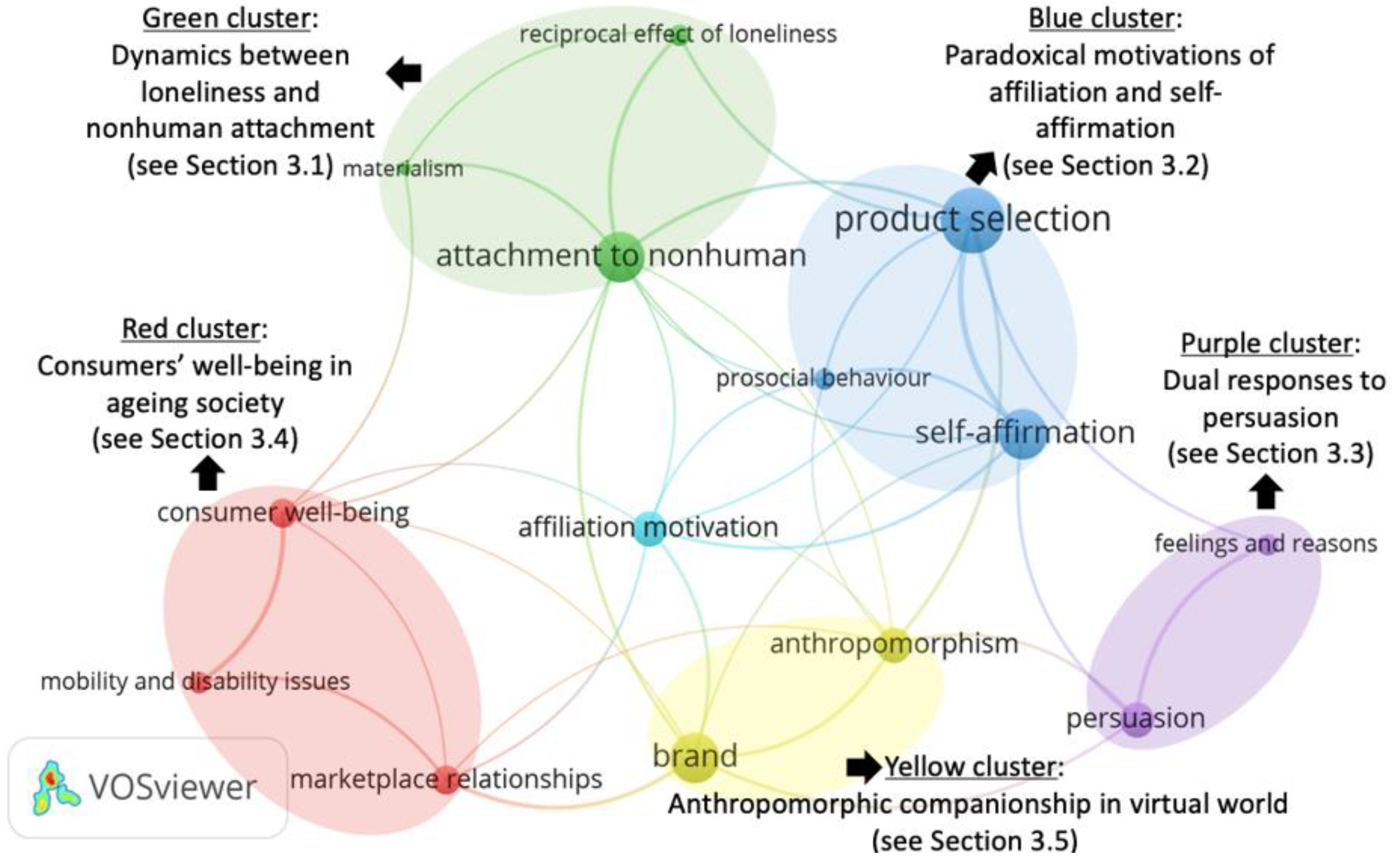

2.3.2. Co-Occurrence Network Analysis: Formation of Theme Clusters

3. Lonely Consumers: Psychological, Commercial and Social Implications

3.1. Psychological Dynamics between Loneliness and Nonhuman Attachment (Green Cluster)

3.2. Paradoxical Motivations of Affiliation and Self-Affirmation Exemplified in Product Selection (Blue Cluster)

3.3. Feelings- and Reasons-Based Information Processing Concerning Persuasions (Purple Cluster)

3.4. Consumer Well-Being in an Ageing Society (Red Cluster)

3.5. Anthropomorphic Companionship in Virtual World (Lemon Cluster)

4. Entering the Post-Pandemic Era: Conclusions and Proposed Research Agenda

4.1. Coping with Psychological Loneliness with New Habits

- To what extent does COVID-19 drive consumers’ adoption of in-door activities (e.g., reading, cooking, gardening and using social media), and to what extent do consumers attach to these activities to cope with loneliness during COVID-19?

- What activities ‘die’ with COVID-19 and ‘survive’ and become the new habits in the post-pandemic era? How are these two types of activities characterised?

- How do new habits impact consumers’ loneliness when social distancing is no longer practised? Does a virtuous or vicious cycle exist between the new habits and consumers’ loneliness?

- Comparing the pre- and post-pandemic situations at a macro-level, do the new habits reduce or increase the loneliness level of the general population?

- How do the new habits impact on consumers’ feelings of fear, uncertainty, confusion and distrust in official discourses associated with the pandemic-induced loneliness? Comparing the before and after pandemic situations at a macro level, do the new habits decrease or increase the negative feelings associated with consumers’ loneliness?

4.2. Changing Market Segments of Loners and Conformers

- To what extent do lonely consumers demonstrate the characteristics of ‘loners’ (‘conformer’) in the post-pandemic era?

- What are the consumer segments and how large are the segments if the market of lonely consumers is segmented using the characteristics identified in the above question? In addition to ‘loners’ and ‘conformers’, what are the other segments that may demonstrate the mixed characteristics?

- To what extent does the pandemic lead to a shrunk/enlarged segment of ‘loners’/’conformers’?

- Considering different cultural contexts, how should the persuasion messages (e.g., cognition- or affect-based) be designed for commercial or social purposes leading to desirable outcomes (e.g., to promote healthy food and COVID-19 vaccine)?

- Comparing lonely consumers belonging to different age groups, that is adolescences, working adults and retired elderlies, what are the most effective persuasion strategies (cognition- or affect-based) that lead to behavioural changes for commercial or social purposes?

4.3. Empowering the Disadvantaged with Technologies

- To what extent does the lack of digital resources (e.g., skills and knowledge) create social isolation and loneliness among the disadvantaged consumers?

- To what extent does COVID-19 contribute to the diffusion of digital technologies among the disadvantaged consumers?

- To what extent do the anthropomorphic products (e.g., service robots) replace consumers’ needs for social interactions, especially for the disadvantaged consumers?

- How should resources be coordinated to enhance the well-being (e.g., informational, physical health and mental health) of the disadvantaged consumers?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Source | Key Point | Key Theme | Assigned Cluster * |

| Chen, Wan and Levy [67] | Socially excluded consumers show preferences for anthropomorphised brands in seeking for affiliation; the resulted band-consumer relationship is influenced by consumers’ attributions of causes of social isolation. | Anthropomorphism; Brand; Marketplace relationships; Internal and external attribution; Affiliation motivation | Commercial implications |

| Darcy, Yerbury and Maxwell [64] | Mobile technologies work as assistant technology to support senior people with disability. | Assistant technology; Digital inequality; Mobility and disability issues | Social implications |

| Das, Echambadi, McCardle and Luckett [31] | Lonely consumers are more likely to use the web for information searching. | Personality | Psychological implications |

| David and Roberts [38] | Phone snubbed consumers experience social isolation which leads them to social media to regain a sense of inclusion. | Phubbed; Attachment to nonhuman; Reciprocal effect of loneliness | Psychological implications |

| Dennis, Alamanos, Papagiannidis and Bourlakis [17] | Multi-channel shopping increases the happiness and well-being of socially excluded consumers, such as consumers with mobility/disability issues. | Multi-channel shopping; Mobility and Disability issues; Consumer well-being | Social implications |

| Dennis, Bourlakis, Alamanos, Papagiannidis and Brakus [62] | social isolation leads consumers to participate in multi-channel shopping, which co-create values for consumers and shopping channels. | Value co-creation; Multi-channel shopping; Mobility and disability issues; Consumer well-being | Social implications |

| Donthu and Gilliland [26] | Single shoppers by choice or by circumstance demonstrate some unique shopping styles to compensate the feeling of loneliness, including variety seeking, risk aversion, price consciousness, brand consciousness, impulsiveness and TV watching. | Solo shopper; Brand; Impulsive or compulsive buying; Risk-taking | Commercial implications |

| Duclos, Wan and Jiang [37] | social isolation increases the instrumental value of money which leads consumers to make riskier financial decision | Instrumentality of money; Risk-taking; Gambling | Psychological implications |

| Feng [69] | Loneliness influences consumers’ responses to anthropomorphic products; product types play a role as well. | Product Selection; Anthropomorphism; Utilitarian and hedonic products | Commercial implications |

| Fitch [24] | The accessibility of local food and retail stores is assessed for socially excluded consumers | Retail reform; Accessibility; Mobility and disability issues | Social implications |

| Gao and Mattila [49] | Socially excluded consumers favour distinctive (vs. popular) green hotels due to self-affirmation motivation. | Self-affirmation; Green consumption; Prosocial behaviour; Product selection; Distinctive and popular products | Commercial implications |

| Gentina, Shrum and Lowrey [39] | Loneliness leads to passive and active coping strategies associated with different types of materialism, which increases or decreases unethical behaviours among young consumers | Materialism; Unethical behaviours | Psychological implications |

| Goodwin and Lockshin [27] | The concept of solo shoppers is proposed and differentiated from lonely shoppers. | Solo shopper; Stereotypes | Commercial implications |

| Guèvremont and Grohmann [70] | Socially excluded consumers are more emotionally attached to authentic brand in seeking for belongingness | Brand; Attachment to nonhuman; Self-affirmation | Commercial implications |

| Guo, Zhang, Liao and Wu [47] | Socially excluded consumers engage with green consumption as a signal to gain social inclusion. | Green consumption; Prosocial behaviour; Costly signalling; Self-sacrifice | Commercial implications |

| Hart and Royne [65] | Loneliness enhances consumers’ responses to anthropomorphism appeals in the case of advertising messages, leading to a more positive attitude toward the brand | Anthropomorphism; Brand; Persuasion | Commercial implications |

| Her and Seo [2] | Anticipated loneliness reduces consumers’ intention to dine alone in public restaurant. | Sole shopper; | Commercial implications |

| Hwang and Mattila [44] | social isolation causes negative emotions (e.g., loneliness) and a sense of losing control which influences consumers’ attitude toward the brand. The relationships are more salient among female consumers. | Gender; Brand; | Commercial implications |

| Jiang, Li, Li and Li [54] | Cultural influences (individualism and collectivism) moderate socially excluded consumers’ responses to external persuasions; Consumers under individualism (collectivism) culture are more responsive to feelings- (reasons-)based advertisement. | Culture; Individualism and collectivism; Persuasion; Feelings and reasons; | Commercial implications |

| Jiang, et al. [71] | Socially excluded consumers who have a present- (future-) orientation tend to exert less (more) self-regulation. | Self-regulation; Time orientation | Social implications |

| Kemp, Moore and Cowart [52] | Lonely consumers respond more favourably to self-referent advertising appeals | Persuasion; Self-affirmation | Commercial implications |

| Kim and Jang [18] | Lonely consumers tend to cope with loneliness with experiential consumptions such as dining out, travel and drink. Age differences are explored. | Experiential consumption | Social implications |

| Kim, Kang and Kim [63] | Loneliness leads to older consumers’ mall shopping motivation which can be consumption-related and experiential-related. | Shopping motivation; Experiential and material products | Social implications |

| Kim, Kim and Kang [58] | Young consumers’ loneliness motivates their media use and shopping behaviour | Shopping motivation | Social implications |

| Lastovicka and Sirianni [40] | Loneliness enhances consumers’ love of material possession | Materialism; Attachment to nonhuman; Consumer well-being | Psychological implications |

| Lee and Shrum [6] | Social isolation threatens the differential needs of consumers; the threatened efficacy needs (explicitly rejected) triggers conspicuous consumption, whereas the threatened relational needs (implicitly ignored) triggers prosocial behaviours. | Prosocial behaviour; Conspicuous consumption; Differential needs hypothesis; Self-affirmation; Affiliation motivation | Commercial implications |

| Lee, Shrum and Yi [45] | Consumers’ behavioural responses to social isolation are dependent on the cultural norm where the exclusion is communicated; norm-congruent communications lead to prosocial behaviour and counter-normative communications lead to conspicuous consumption | Prosocial behaviour; Conspicuous consumption; Differential needs hypothesis; Culture; High-context and low-context communications | Commercial implications |

| Lim and Kim [60] | Older consumers’ loneliness leads to their parasocial interactions with TV host, which increase their purchasing intention of TV home shopping. | TV home shopping; Parasocial interaction; Mobility and disability issues; Marketplace relationships | Social implications |

| Lim and Kim [59] | Older consumers’ loneliness motivates their TV home shopping behaviour, which creates a sense of telepresence and leads to consumers’ satisfaction with TV shopping | TV home shopping; Telepresence; Shopping motivation | Social implications |

| Loughran Dommer, Swaminathan and Ahluwalia [50] | Socially excluded consumers use a brand to differentiate themselves horizontally and vertically; Low self-esteem consumers increase perceptions of group heterogeneity (seek to protect their future belongingness) and subsequently increase their attachment to horizontal (vertical) brands | Brand; Attachment to nonhuman; Affiliation motivation | Commercial implications |

| Lu and Sinha [53] | Social isolation impairs consumers’ cognitive thinking, which makes them more responsive to affect-based persuasion. | Feelings and reasons; Persuasion | Commercial implications |

| Mead, Baumeister, Stillman, Rawn and Vohs [33] | Socially excluded consumers use spending and consumption to seek affiliation, where they sacrifice personal and financial well-being for the sake of social well-being. | Affiliation motivation; Spending and consumption; Self-sacrifice | Psychological implications |

| Mittal and Silvera [3] | Loneliness and gender predict consumers’ attachment to purchases (material and experiential), which explain future purchase intentions. | Extended self; Attachment to nonhuman; Gender; Product selection; Experiential and material products | Commercial implications |

| Mourey, Olson and Yoon [30] | Consumers attach to anthropomorphic products as an alternative to interpersonal interactions to gain social assurance. | Anthropomorphism; Attachment to nonhuman; Prosocial behaviour; Product selection; Social assurance | Psychological implications |

| O Sullivan and Richardson [1] | Consumption communities function as a self-help group which provides ‘treatment’ for loneliness. | Community; Gender | Social implications |

| Orth, Cornwell, Ohlhoff and Naber [68] | Consumers’ loneliness and anthropomorphism tendency moderate their responses to brand visual, leading to brand liking | Brand; Anthropomorphism; Persuasion | Commercial implications |

| Pieters [34] | Loneliness contributes to materialism, and materialism reinforces consumers’ loneliness to a weaker extent depending on the subtypes of materialism. | Materialism; Reciprocal effect of loneliness; Attachment to nonhuman | Psychological implications |

| Rippé, Smith and Dubinsky [5] | Loneliness (social and emotional) contributes to consumers’ interaction with in-store salesperson, which leads to purchase intention and retail patronage | In-store interaction; Marketplace relationships | Social implications |

| Smith, Rippé and Dubinsky [4] | Loneliness (social, emotional and physical isolation) leads to enjoyment of in-store interaction with salespersons. | In-store interaction; Marketplace relationships | Social implications |

| Snyder and Newman [57] | Lonely consumers express a higher intention to join brand communities in seek for belongingness. | Brand; Community; Marketplace relationships; Affiliation motivation; Consumer well-being | Social implications |

| Su, Jiang, Chen, DeWall, Dahl and Lee [51] | Social isolation threatens consumers’ sense of control. The motivation of control restoration and belongingness maintenance influence their switching behaviour. | Switching behaviour; Control restoration; Affiliation motivation | Commercial implications |

| Su, Wan and Jiang [25] | Social isolation causes consumers’ psychological emptiness, which enhances their preference for visual density. | Visual preference; Density; Psychological emptiness; Product selection | Commercial implications |

| Suresh and Biswas [32] | Loneliness is posited as an antecedent factor to internet addiction which leads to compulsive buying online among young consumers | Impulsive or compulsive buying; Attachment to nonhuman; Internet addiction | Psychological implications |

| Tan and Hair [35] | Loneliness triggers consumers’ ethnocentrism which leads favourable responses to domestic products; the ethnocentrism reinforces consumers’ loneliness | Product selection; Domestic and foreign products; Ethnocentrism; Reciprocal effect of loneliness | Psychological implications |

| Thomas and Saenger [7] | Social isolation increases consumers’ motivation to affiliate which modifies their perception of crowded retailing setting and associated shopping behaviour | Visual preference; Affiliation motivation; Crowdedness | Commercial implications |

| Wan, Xu and Ding [41] | Stable social isolation leads to consumers’ preference for distinctive products due to the self-affirmative motivation. | Product selection; Distinctive and popular products; Self-affirmation; Stable or unstable exclusion | Commercial implications |

| Wang, Zhu and Shiv [42] | Lonely consumers are more likely to choose minority-endorsed product to maintain their feelings of loneliness, but they choose to conform with the majority when their choice is under public context. | Self-affirmation; Product selection; Affiliation motivation; Distinctive and popular products | Commercial implications |

| Wang and Lalwani [36] | Culture (independent and interdependent) moderates consumers’ impression management pursuit due to social isolation; interdependent consumers tend to give up impression management when socially excluded. | Impression management; Culture; Independent and interdependent; In-group identification | Psychological implications |

| Wang and Sirois [43] | Loneliness influences consumers’ visual preference of product, i.e., warmer products are favoured over darker products | Product selection; Visual preference; Warmer and darker products | Commercial implications |

| Wei [61] | Introversion predicts more severe loneliness due to social distancing during COVID-19. | Social distancing; Personality; COVID-19 | Social implications |

| Whelan, Johnson, Marshall and Thomson [56] | Consumers with interpersonal insecurity turn to marketplace relationships (with brands and salespersons) as a compensation strategy. | Brand; Marketplace relationships; Anxiety and avoidance | Social implications |

| Xie, Charness, Fingerman, Kaye, Kim and Khurshid [11] | Older consumers are disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which requires solutions | Covid-19; Social distancing; | Social implications |

| Xie, Chen and Guo [66] | Social isolation moderates consumers’ privacy concern when using anthropomorphic online services and subsequent purchase behaviour. | Anthropomorphism; Privacy | Commercial implications |

| Xu and Jin [55] | When consumers are socially excluded, they are more likely to have a problem-solving tendency choose utilitarian products. By contrast, when consumers imagine being socially excluded in the future, they are more likely to use emotions to solve problems and choose hedonic products. | Product selection; Utilitarian and hedonic products; Time orientation; Feelings and reasons | Commercial implications |

| Yang, Yu, Wu and Qi [46] | Socially excluded consumers prefer experiential purchases over material to fulfil relational needs. The effect is stronger among consumers with interdependent self-construal. | Product selection; Experiential and material products; Independent and interdependent; Self-construal | Commercial implications |

| Yi, Kim and Hwang [48] | Socially excluded consumers tend to choose ordinary products to restore threatened self-concept. | Product selection; Distinctive and popular products | Commercial implications |

| * Cell colours indicate the assigned clusters of the respective papers in the co-occurrence network. | |||

References

- Sullivan, M.; Richardson, B. Close knit: Using consumption communities to overcome loneliness. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 2825–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Her, E.; Seo, S. Why not eat alone? The effect of other consumers on solo dining intentions and the mechanism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 70, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Silvera, D.H. Never truly alone, we always have our purchases: Loneliness and sex as predictors of purchase attachment and future purchase intentions. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, e67–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Rippé, C.B.; Dubinsky, A.J. India’s lonely and isolated consumers shopping for an in-store social experience. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 722–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippé, C.B.; Smith, B.; Dubinsky, A.J. Lonely consumers and their friend the retail salesperson. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shrum, L.J. Conspicuous consumption versus charitable behavior in response to social exclusion: A differential needs explanation. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Saenger, C. Feeling excluded? Join the crowd: How social exclusion affects approach behavior toward consumer-dense retail environments. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. Impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, D.l.A.; Makowski, L.M.; Troche, S.J.; Schlegel, K. Loneliness and well-being during the Covid-19 pandemic: Associations with personality and emotion regulation. J. Happiness Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Kretzler, B.; König, H.-H. Multimorbidity, loneliness, and social isolation. A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Charness, N.; Fingerman, K.; Kaye, J.; Kim, M.T.; Khurshid, A. When Going Digital Becomes a Necessity: Ensuring Older Adults’ Needs for Information, Services, and Social Inclusion During COVID-19. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2020, 32, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Jeong, G.-C.; Yim, J. Consideration of the psychological and mental health of the elderly during COVID-19: A theoretical review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Lu, N. Social capital and mental health among older adults living in urban China in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoszek, A.; Walkowiak, D.; Bartoszek, A.; Kardas, G. Mental well-being (Depression, loneliness, insomnia, daily life fatigue) during COVID-19 related home-confinement—A study from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Hui, B.P.H.; Wan, E.Y.F. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during covid-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Salgado, J.; Andrés-Villas, M.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Díaz-Milanés, D.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Related health factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, C.; Alamanos, E.; Papagiannidis, S.; Bourlakis, M. Does social exclusion influence multiple channel use? The interconnections with community, happiness, and well-being. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jang, S. Therapeutic benefits of dining out, traveling, and drinking: Coping strategies for lonely consumers to improve their mood. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 67, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Routledge and Kogan Paul: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Trigg, A.B. Veblen, Bourdieu and conspicuous consumption. J. Econ. Issues 2001, 35, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvagno, M.; Gummesson, E.; Mele, C.; Polese, F.; Dalli, D. Theory of value co-creation: A systematic literature review. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2014, 24, 643–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J.; Slack, F. Conducting a literature review. Manag. Res. News 2004, 27, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Hubbard, P. Who is disadvantaged? Retail change and social exclusion. Int. Rev. RetailDistrib. Consum. Res. 2001, 11, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, D. Measuring convenience: Scots’ perceptions of local food and retail provision. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2004, 32, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Wan, E.W.; Jiang, Y. Filling an Empty Self: The Impact of Social Exclusion on Consumer Preference for Visual Density. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 808–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Gilliland, D.I. The single consumer. J. Advert. 2002, 42, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C.; Lockshin, L. The solo consumer: Unique opportunity for the service marketer. J. Serv. Mark. 1992, 6, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourey, J.A.; Olson, J.G.; Yoon, C. Products as Pals: Engaging with Anthropomorphic Products Mitigates the Effects of Social Exclusion. J. Consum. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Echambadi, R.; McCardle, M.; Luckett, M. The effect of interpersonal trust, need for cognition, and social loneliness on shopping, information seeking and surfing on the web. Mark. Lett. 2003, 14, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, A.S.; Biswas, A. A Study of Factors of Internet Addiction and Its Impact on Online Compulsive Buying Behaviour: Indian Millennial Perspective. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2019, 21, 1448–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, N.L.; Baumeister, R.F.; Stillman, T.F.; Rawn, C.D.; Vohs, K.D. Social exclusion causes people to spend and consume strategically in the service of affiliation. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 902–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R. Bidirectional Dynamics of Materialism and Loneliness: Not Just a Vicious Cycle. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.Y.D.; Hair, M. The reciprocal effects of loneliness and consumer ethnocentrism in online behavior. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Lalwani, A.K. The interactive effect of cultural self-construal and social exclusion on consumers’ impression management goal pursuit. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos, R.; Wan, E.W.; Jiang, Y. Show me the honey! Effects of social exclusion on financial risk-taking. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.E.; Roberts, J.A. Phubbed and Alone: Phone Snubbing, Social Exclusion, and Attachment to Social Media. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2017, 2, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentina, E.; Shrum, L.J.; Lowrey, T.M. Coping with Loneliness Through Materialism: Strategies Matter for Adolescent Development of Unethical Behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 152, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastovicka, J.L.; Sirianni, N.J. Truly, Madly, Deeply: Consumers in the Throes of Material Possession Love. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, E.W.; Xu, J.; Ding, Y. To be or not to be unique: The effect of social exclusion on consumer choice. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, R.; Shiv, B. The Lonely Consumer: Loner or Conformer? J. Consum. Res. 2012, 38, 1116–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sirois, F. Drawn to the light: Loneliness predicts a preference for products in brightness but not darkness. Adv. Consum. Res. 2016, 44, 670–672. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Y.; Mattila, A.S. Feeling left out and losing control: The interactive effect of social exclusion and gender on brand attitude. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shrum, L.J.; Yi, Y. The role of cultural communication norms in social exclusion effects. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yu, H.; Wu, J.; Qi, D. To do or to have? Exploring the effects of social exclusion on experiential and material purchases. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 23, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liao, J.; Wu, F. Social Exclusion and Green Consumption: A Costly Signaling Approach. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 535489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Hwang, J.W. Climbing down the ladder makes you play it safe. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.L.; Mattila, A.S. The Impact of Option Popularity, Social Inclusion/Exclusion, and Self-affirmation on Consumers’ Propensity to Choose Green Hotels. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 136, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran Dommer, S.; Swaminathan, V.; Ahluwalia, R. Using Differentiated Brands to Deflect Exclusion and Protect Inclusion: The Moderating Role of Self-Esteem on Attachment to Differentiated Brands. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Z.; DeWall, C.N.; Dahl, D.; Lee, L. Social Exclusion and Consumer Switching Behavior: A Control Restoration Mechanism. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, E.; Moore, D.J.; Cowart, K. Me, Myself, and I: Examining the Effect of Loneliness and Self-Focus on Message Referents. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2016, 37, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.-C.; Sinha, J. Speaking to the heart: Social exclusion and reliance on feelings versus reasons in persuasion. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Li, L. The effect of social exclusion on persuasiveness of feelings versus reasons in advertisements: The moderating role of culture. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 1252–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Jin, X. How social exclusion and temporal distance influence product choices: The role of coping strategies. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, J.; Johnson, A.R.; Marshall, T.C.; Thomson, M. Relational Domain Switching: Interpersonal Insecurity Predicts the Strength and Number of Marketplace Relationships. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, D.G.; Newman, K.P. Reducing consumer loneliness through brand communities. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Kim, E.Y.; Kang, J. Teens’ mall shopping motivations: Functions of loneliness and media usage. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2003, 32, 140–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.M.; Kim, Y.-K. Older consumers’ TV shopping: Emotions and satisfaction. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.M.; Kim, Y.-K. Older consumers’ Tv home shopping: Loneliness, parasocial interaction, and perceived convenience. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M. Social distancing and lockdown: An introvert’s paradise? An empirical investigation on the association between introversion and the psychological impact of COVID19-related circumstantial changes. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 561609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.; Bourlakis, M.; Alamanos, E.; Papagiannidis, S.; Brakus, J.J. Value co-creation through multiple shopping channels: The interconnections with social exclusion and well-being. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2017, 21, 517–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Kang, J.; Kim, M. The relationships among family and social interaction, loneliness, mall shopping motivation, and mall spending of older consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2005, 22, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; Yerbury, H.; Maxwell, H. Disability citizenship and digital capital: The case of engagement with a social enterprise telco. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2018, 22, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.; Royne, M.B. Being Human: How Anthropomorphic Presentations Can Enhance Advertising Effectiveness. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2017, 38, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, K.; Guo, X. Online anthropomorphism and consumers’ privacy concern: Moderating roles of need for interaction and social exclusion. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.P.; Wan, E.W.; Levy, E. The effect of social exclusion on consumer preference for anthropomorphized brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.R.; Cornwell, T.B.; Ohlhoff, J.; Naber, C. Seeing faces: The role of brand visual processing and social connection in brand liking. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 47, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W. When lonely people encounter anthropomorphic products. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2016, 44, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guèvremont, A.l.; Grohmann, B. The brand authenticity effect: Situational and individual-level moderators. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 602–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yang, Z.; Sun, P.; Xu, M. When does social exclusion increase or decrease food self-regulation: The moderating role of time orientation. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Theme * | Brief Description | Occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| Production selection | The impacts of perceived loneliness or social isolation on consumers’ choice or preference of products or services | 12 |

| Brand | Response to brand communities, such as brand attitude and brand participation | 9 |

| Affiliation motivation | Fundamental motivation of belongingness to a social group, which guides lonely consumers’ consumption behaviours | 8 |

| Attachment to nonhuman | Attachment to materials or products as a replacement of interpersonal relationships | 8 |

| Self-affirmation | Confirmation and enhancement of self-identity and personal uniqueness, which guide lonely consumers’ consumption behaviours | 7 |

| Anthropomorphism | Built-in human-like features in nonhuman agents, appealing to lonely consumers’ empathy and liking | 6 |

| Marketplace relationships | Relationships with an in-store salesperson, hosts of e-commerce sites or brands due to lack of quality social interactions in consumers’ daily life | 6 |

| Mobility and disability issues | Physiological restrictions that cause loneliness and social isolation, which are often associated with senior consumers | 5 |

| Persuasion | External cues such as advertisements and promotional information that appeal to consumers’ loneliness, and the associated responses from consumers | 5 |

| Prosocial behaviour | Behaviours for social well-being, such as helping others, donation and green consumption, which are demonstrated by lonely consumers to gain social inclusion | 5 |

| Consumer well-being | Physical and mental conditions of consumers, which are often impaired by loneliness but improved via several coping strategies | 4 |

| Distinct and popular products | Preferences for minority- or majority-endorsed products, depending on consumers’ motivations and needs to cope with loneliness | 4 |

| Cultural effects | Macro-level cultural impacts on lonely consumers, such as collectivism vs. individualism, independent vs. interdependence, low-context vs. high-context | 3 |

| Experiential and material products | Preferences for experiential or material consumption by lonely consumers | 3 |

| Feelings and reasons | Information processing mechanisms, which can be affect-based or cognition-based in response to persuasions | 3 |

| Gender differences | Gender as a moderator of various behaviours of lonely shoppers | 3 |

| Materialism | Importance attached to owning symbolic material possessions, which is not only the cause but also a consequence of loneliness | 3 |

| Reciprocal effect of loneliness | Consequences of loneliness, which in turn reinforce loneliness, which depicts the dynamic impacts of loneliness, such as materialism | 3 |

| Solo shopper | Consumers who engage with consumption activities alone, who may or may not be lonely | 3 |

| Visual preferences | Aesthetic preferences, which may be modified by consumers’ state of loneliness, such as a preference for warmth and crowdedness | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D.; Yuen, K.F. Rise of ‘Lonely’ Consumers in the Post-COVID-19 Era: A Synthesised Review on Psychological, Commercial and Social Implications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020404

Wang X, Wong YD, Yuen KF. Rise of ‘Lonely’ Consumers in the Post-COVID-19 Era: A Synthesised Review on Psychological, Commercial and Social Implications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):404. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020404

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xueqin, Yiik Diew Wong, and Kum Fai Yuen. 2021. "Rise of ‘Lonely’ Consumers in the Post-COVID-19 Era: A Synthesised Review on Psychological, Commercial and Social Implications" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020404

APA StyleWang, X., Wong, Y. D., & Yuen, K. F. (2021). Rise of ‘Lonely’ Consumers in the Post-COVID-19 Era: A Synthesised Review on Psychological, Commercial and Social Implications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020404