The Strengthening Mechanism of the Relationship between Social Work and Public Health under COVID-19 in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Work and Public Health

1.2. Health Social Work: Its Practice in China

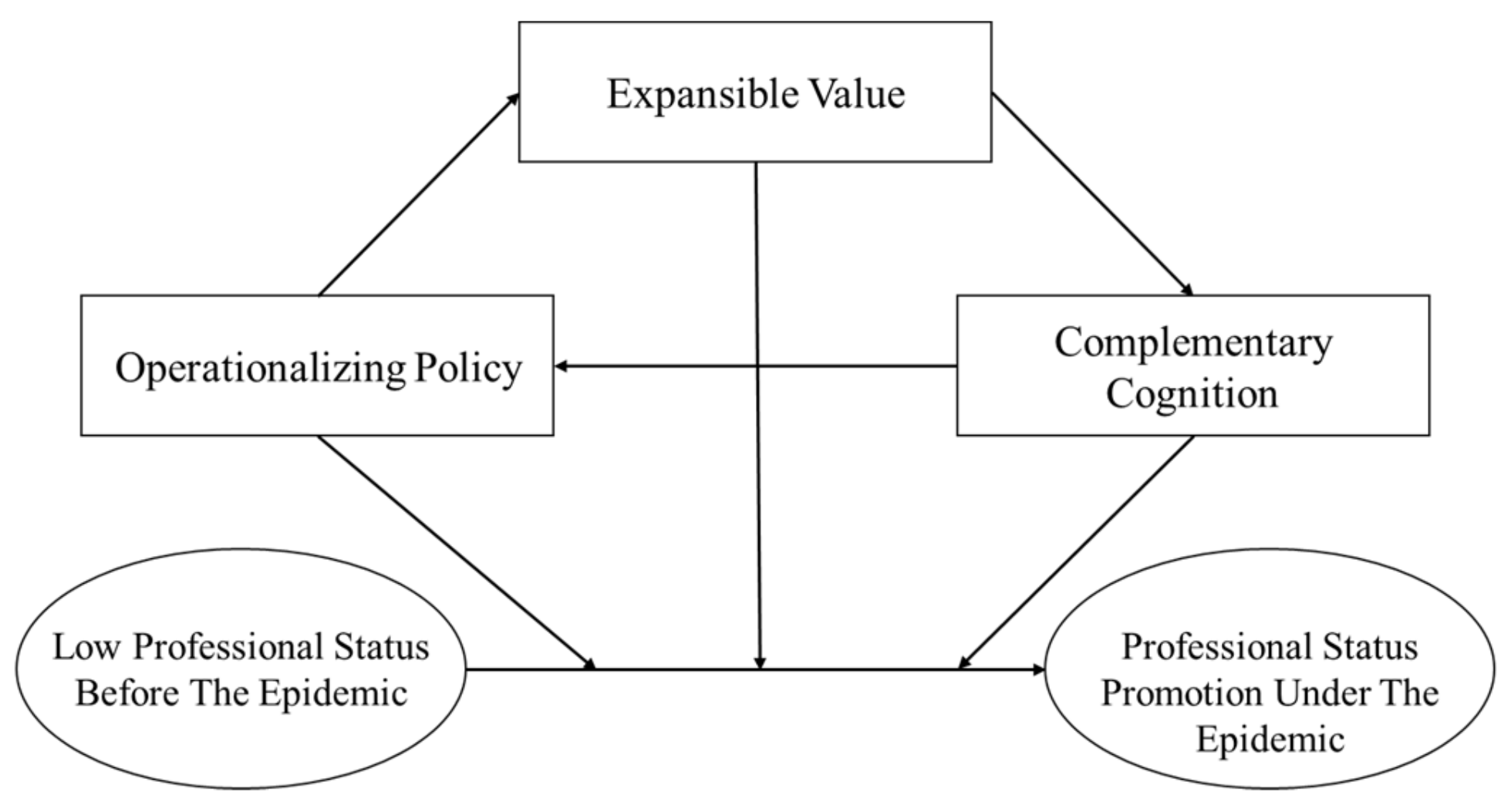

2. Conceptual Framework: Professional Legitimacy

3. Methodology

- What is the current organizational structure of the Social Work Department? If there have been changes in the development process, have there been any impacts on you before and after the changes?

- Do you think that the current professional development program, as far as it is concerned, can meet the professional needs of health social work?

- During this epidemic, in your opinion, how did social workers perform, did they respond to the needs and expectations of the community, and to what extent did they respond? In the future, is it possible for social workers to obtain preventive content when responding to possible epidemics or other social events?

- What are your views on the current and future development of health social work as a whole? What do you think are the factors that affect the development of health social workers?

4. Findings: Three Mechanisms of Health Social Work’s Legitimacy Image

4.1. Operationalizing Policy

“Social workers, to be honest, are not so professional in all fields. But for example, the field of health social work is a field that can significantly reflect the professional level of social work. The area that can reflect professionalism is what we want to further promote through policies.”(Policy, P2)

“In the opinions issued by the 12 departments in 2016, it has been made clear that social workers should be set up in hospitals in the medical field, and the health and Family Planning Commission is also a countersignature unit, which should be supported at the policy level. But for more specific policies, at present, there is no deeper promotion.”(Policy, P2)

“The priority now is to make the leaders at the national level clear about the specific role and importance of social workers in the medical system.”(Academic, A1)

4.2. Extending Value

“If I want to deal with the medical disputes, I may think about whether social workers can play a role from a lot of professional perspectives. Of course, I find that they do not seem to play many roles, because I find that when dealing with medical disputes, you will be more effective if you have experience. I find that many experienced executives will do better than our social workers.”(Hospital, HC2)

“Social workers in the hospital are awarded as Professional and technical positions like doctors and nurses, not administrative positions. We need to prove our professionalism, including the scientificity and preciseness of our services. We need to show ourselves in some ways like scientific research.”(Hospital, HG1)

“The most important characteristic of the cabin is that the patients in the cabin have a very high demand for order. The number of medical staff is very limited, they are too busy to do all the things… In short, the management of the cabin hospital is very chaotic. Our team provided management and support, immediately reduce much work of medical staff, and the whole order becomes a lot smoother. For example, some hygiene or common-sense questions can be answered by our social workers… There is also psychological crisis intervention, we will deal with the case immediately… Later, they had a high degree of trust in us, including hospitals, which issued notices and handled discharge certificates through our online community.”(Academic, W1)

4.3. Completing Justification

“In our hospital, social workers mainly provide patients with some information about medical expenses; when patients are hospitalized, they provide admission procedures, location guidance of various departments in the hospital, and information about attending doctors …. There are also some recreational activities and volunteer services, which are the most popular among us (doctors) and patients...”(Hospital, HD3)

“Some hospitals are doing worse, and there is an extreme situation, that is, they do not care about anything…I entrust you (social workers), then you do it. Anyway, we do not understand any knowledge of you…Social workers must cooperate in many aspects, but cross-professional cooperation may be very difficult.”(Organization, O3)

“Maybe society has no expectations for professional social workers because many places don’t know what social workers are. But at least this time we Let a lot of people know what social workers are… When we first entered the cabin, the medical staff were also very suspicious, but we relied on professional services to let the medical staff and patients recognize it. If we still doing something Worthless, they will not have social work in his mind, and they don’t know how to use us (social work).”(Academic, W1)

“Asking about the physical condition of the residents, taking their temperature, doing a good job in registration, sending masks and distributing epidemic prevention manuals.”(Organization, O4)

5. Discussion

5.1. Legitimacy as a Mechanism

5.2. The Future and Limitations for the Professional Development of Health Social Work in China

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, C.; Cheng, J.; Zou, J.; Duan, L.; Campbell, J.E. Health-Related Quality of Life of Hospitalized COVID-19 Survivors: An Initial Exploration in Nanning City, China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 274, 113748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Association of Schools of Social Work COVID-19 and Social Work: A Collection of Country Reports. Available online: https://www.iassw-aiets.org/covid-19/5369-covid-19-and-social-work-a-collection-of-country-reports/ (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China Urgent Notice from the Ministry of Civil Affairs and the National Health Commission on Further Mobilizing Urban and Rural Community Organizations to Carry Out the Prevention and Control of Pneumonia Outbreaks of New Coronavirus Infection. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202001/1d27e24c56fb47e3bb98d7e39c9ccb17.shtml (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Ruth, B.J.; Marshall, J.W. A History of Social Work in Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, S236–S242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, G.W.; Sager, A.; Selig, S.; Antonelli, R.; Morton, S.; Hirsch, G.; Lee, C.R.; Ortiz, A.; Fox, D.; Lupi, M.V.; et al. No Equity, No Triple Aim: Strategic Proposals to Advance Health Equity in a Volatile Policy Environment. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, S223–S228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruth, B.J.; Wachman, M.K.; Marshall, J.W.; Backman, A.R.; Harrington, C.B.; Schultz, N.S.; Ouimet, K.J. Health in All Social Work Programs: Findings From a US National Analysis. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, S267–S273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruth, B.J.; Marshall, J.W.; Wachman, M.; Marbach, A.; Choudhury, N.S. More than a Great Idea: Findings from the Profiles in Public Health Social Work Study. Soc. Work Public Health 2020, 35, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, T.; Keefe, R.H.; Ruth, B.J.; Cox, H.; Maramaldi, P.; Rishel, C.; Rountree, M.; Zlotnik, J.; Marshall, J. Advancing Social Work Education for Health Impact. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, S229–S235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederbaum, J.A.; Ross, A.M.; Ruth, B.J.; Keefe, R.H. Public Health Social Work as a Unifying Framework for Social Work’s Grand Challenges. Soc. Work 2019, 64, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbutt, D. Collaborative Practice for Public Health; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers, P.L.; Mallinger, G.; Bragg-Underwood, T. Promoting Socially Just Healthcare Systems: Social Work’s Contribution to Patient Navigation. ASW 2017, 17, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beder, J. Hospital Social Work: The Interface of Medicine and Caring; Routledge, Taylor & Frances Group: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, R.G.; Sheffield, S. Hospital Social Work: Contemporary Roles and Professional Activities. Soc. Work Health Care 2010, 49, 856–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Zhang, A. Development of Medical Social Work in Shanghai. Encyclopedia of Social Work; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, D. The Suicide Prevention Continuum. Pimatisiwin 2008, 6, 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, L.; Fichtenberg, C.; Alderwick, H.; Adler, N. Social Determinants of Health: What’s a Healthcare System to Do? J. Healthc. Manag. 2019, 64, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachur, C.; Singer, B.; Hayes-Conroy, A.; Horwitz, R.I. Social Determinants of Treatment Response. Am. J. Med. 2018, 131, 480–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.A.; Kumanyika, S.; Fielding, J.; LaVeist, T.; Borrell, L.N.; Manderscheid, R.; Troutman, A. Health Disparities and Health Equity: The Issue Is Justice. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, S149–S155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galea, S.; Tracy, M.; Hoggatt, K.J.; DiMaggio, C.; Karpati, A. Estimated Deaths Attributable to Social Factors in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mymin Kahn, D.; Bulanda, J.J.; Weissberger, A.; Jalloh, S.; Von Villa, E.; Williams, A. Evaluation of a Support Group for Ebola Hotline Workers in Sierra Leone. Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health 2016, 9, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bortel, T.; Basnayake, A.; Wurie, F.; Jambai, M.; Koroma, A.S.; Muana, A.T.; Hann, K.; Eaton, J.; Martin, S.; Nellums, L.B. Psychosocial Effects of an Ebola Outbreak at Individual, Community and International Levels. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Lai, D.W.L. Social Exclusion and Health among Older Chinese in Shanghai, China. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work Dev. 2016, 26, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Victor, B.G.; Hong, J.S.; Wu, S.; Huang, J.; Luan, H.; Perron, B.E. A Scoping Review of Interventions to Promote Health and Well-Being of Left-behind Children in Mainland China. Br. J. Soc. Work 2020, 50, 1419–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fabbre, V.D. The Health and Well-Being of LGBTQ People in Mainland China: The Role of Social Work. Int. Soc. Work July 2020, 002087282094001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. Child Psychiatry in China: Present Situation and Future Prospects. Pediatr. Invest. 2020, 4, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Su, H.; Yao, X.; Wen, M. Hospice and Palliative Care: Development and Challenges in China. CJON 2016, 20, E16–E19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Z. Research on the Quality Hospice Care of Elderly Cancer Patients in China under Social Work Intervention. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2020, 25, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Xu, J. The Historical Review of Chinese Mental Health Policy since 1949. China J. Soc. Work 2020, 13, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Hämäläinen, J.; Chen, Y. Medical Social Work Practice in Child Protection in China: A Multiple Case Study in Shanghai Hospitals. Soc. Work Health Care 2017, 56, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler, S.J.; Webb, J.R. School Social Work: Increasing the Legitimacy of the Profession. Child. Sch. 2009, 31, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J. Social Work Legitimacy: Democratising Research, Policy and Practice in Child Protection. Br. J. Soc. Work 2021, 51, 1168–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. Research on the performance evaluation of social work participation in social governance: Analysis framework based on Legitimacy Theory. Soc. Sci. J. 2019, 6, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, M.; Zhou, Y. From Needs-Driven to Problem-Focused: A Study on the Authority of the Social Work Practice in China. J. Soc. Work. 2019, 4, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. China Social Work against the Background of Social Governance. Soc. Work Manag. 2014, 4, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Toward Recognition: The Development of Professional Social Work in China. Hebei Acad. J. 2013, 33, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Scott, W.R. Organizational Environments: Ritual and Rationality; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K. Conducting Key Informant Interviews in Developing Countries; Agency for International Development: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8039-4653-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, K.H.; Chan, C.K.; Wen, Z. State-NGOs Relationship in the Context of China Contracting out Social Services. Soc. Policy Adm. 2021, 55, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J. What Is the Role of Social Work in China? A Multi-Dimensional Analysis. ASW 2014, 15, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Q.; Fang, G.; Yang, J. The Development and Reform of Public Health in China from 1949 to 2019. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Souleymanov, R. Impacts of HIV/AIDS on Poor and Socially Marginalised Former Commercial Plasma Donors in Rural Central China: Social Work Implications. China J. Soc. Work 2017, 10, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chui, W.H. Rehabilitation Policy for Drug Addicted Offenders in China: Current Trends, Patterns, and Practice Implications. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work Dev. 2018, 28, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lum, T.Y. Role of the Professional Helper in Disaster Intervention: Examples from the Wenchuan Earthquake in China. J. Soc. Work Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 12, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.H.C. From Hospital-Based to Community-Based, the Emerging Healthcare Social Work in China. In Proceedings of the International Social work Conference, Asia, and Pacific Association for Social Work Educators, Hue City, Vietnam, 20–21 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; He, X.; Duan, W. A Reflection on the Current China Social Work Education in the Combat with COVID-19. Soc. Work Educ. 2020, 39, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. The Theoretical Framework, Practice Model and Local Orientation of Public Health Social Work. Soc. Constr. 2020, 7, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberthal, K.G.; Lampton, D.M. Bureaucracy, Politics, and Decision Making in Post-Mao China; University of California Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Miao, G.; Peng, Y. The Development of China’s Social Work and Its Institutional Problems. Ideol. Front 2012, 38, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, B.; Zhang, X.; Wu, L.; Zhu, H.; Chen, B. Why Do Countries Respond Differently to COVID-19? A Comparative Study of Sweden, China, France, and Japan. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, L.K.; Byers, K.V.; Pedrick, L. Policy Practice for Social Workers: New Strategies for a New Era, 1st ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-205-02244-1. [Google Scholar]

- Aviv, I.; Gal, J.; Weiss-Gal, I. Social Workers as Street-Level Policy Entrepreneurs. Public Adm. 2021, 99, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, J.; Weiss-Gal, I. The ‘Why’ and the ‘How’ of Policy Practice: An Eight-Country Comparison. Br. J. Soc. Work 2015, 45, 1083–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potting, M.; Sniekers, M.; Lamers, C.; Reverda, N. Legitimizing Social Work: The Practice of Reflective Professionals. JSI 2010, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McNeece, C.A.; Thyer, B.A. Evidence-Based Practice and Social Work. J. Evid. Based Soc. Work 2004, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCroy, C.W. Logic Models. In Encyclopedia of Social Work; NASW Press and Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-19-997583-9. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, C.; MacFarlane, S.; Ablett, P. The Neoliberal Colonisation of Social Work Education: A Critical Analysis and Practices for Resistance. Adv. Soc. Work Welf. Educ. 2017, 19, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, M. Social Work Education and the Neo-Liberal Challenge: The US Response to Increasing Global Inequality. Soc. Work Educ. 2013, 32, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interviewees | Code | Profiles |

|---|---|---|

| Government Officials (n = 2) | P1 | Former department Director of the National Health Commission of the PRC |

| P2 | Former department Director of the Ministry of Civil Affairs of the PRC | |

| Academic Experts and Scholars (n = 3) | A1 | University Professor |

| A2 | University Associate Professor | |

| A3 | University Associate Professor | |

| Heads of Social Work Organizations (n = 3) | O1 | Social work organization secretary-general |

| O2 | Social service centre Chairman | |

| O3 | Social work organization secretary-general | |

| Experts from Social Work Associations (n = 1) | I1 | Social work association Commissioner |

| Heads of Hospitals and Medical Social Work Departments (n = 6) | HA1 | Vice President of Hospital |

| HB1 | Director of Social Work Department | |

| HC1 | Director of Social Work Department | |

| HD1 | Director of Social Work Department | |

| HE1 | Director of Outpatient Clinic | |

| HF1 | Vice President of Hospital | |

| Frontline Social Workers (n = 6) | HG1 | Medical Social Worker |

| HG2 | Medical Social Worker | |

| HH1 | Medical Social Worker | |

| HC2 | Medical Social Worker | |

| CS1 | Community Social Worker | |

| CS2 | Community Social Worker |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, M. The Strengthening Mechanism of the Relationship between Social Work and Public Health under COVID-19 in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199956

Zheng G, Zhang X, Wang Y, Ma M. The Strengthening Mechanism of the Relationship between Social Work and Public Health under COVID-19 in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):9956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199956

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Guanghuai, Xinyi Zhang, Yean Wang, and Mingzi Ma. 2021. "The Strengthening Mechanism of the Relationship between Social Work and Public Health under COVID-19 in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 9956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199956

APA StyleZheng, G., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., & Ma, M. (2021). The Strengthening Mechanism of the Relationship between Social Work and Public Health under COVID-19 in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 9956. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199956