Structural Equation Model for Developing Person-Centered Care Competency among Senior Nursing Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Aims and Hypotheses

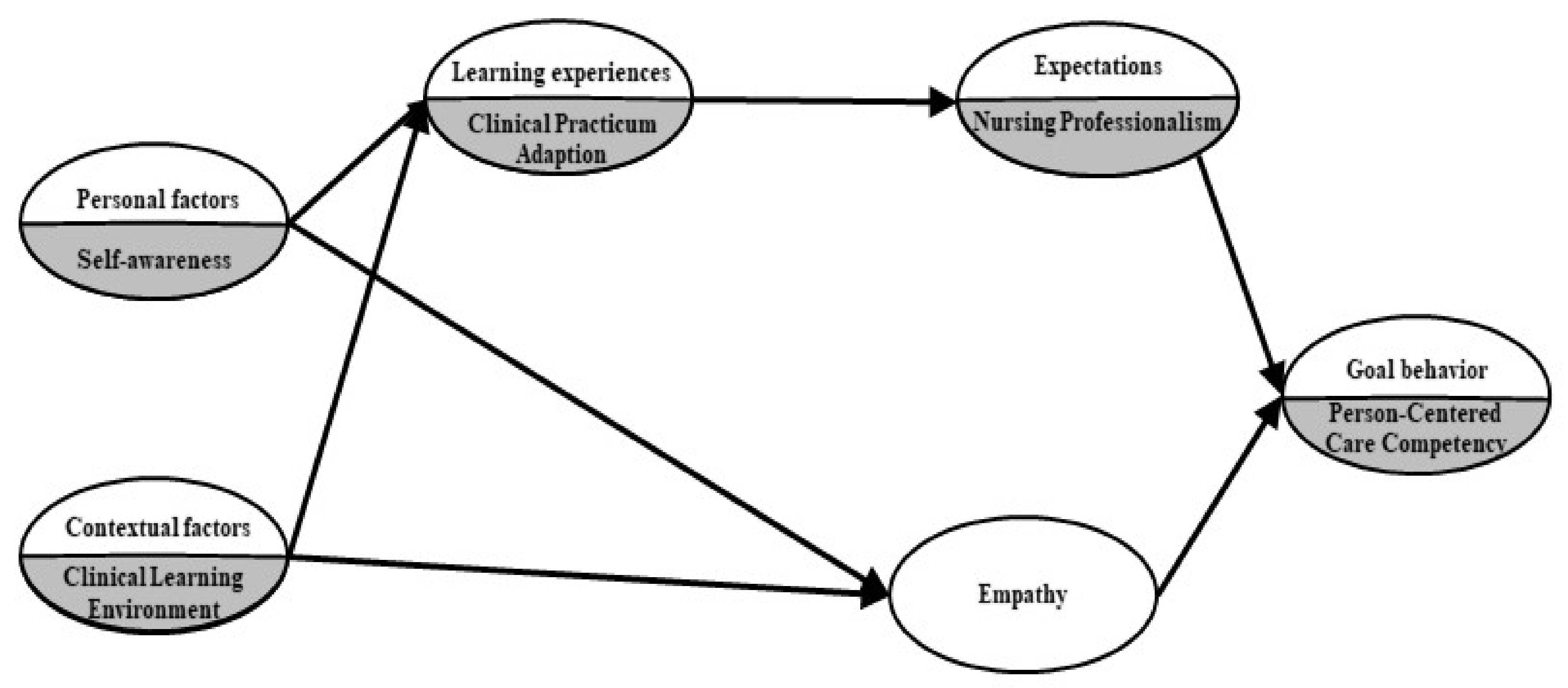

1.2. Conceptual Framework and Hypothetical Model

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Self-Awareness

2.4.2. Clinical Learning Environment

2.4.3. Clinical Practicum Adaptation

2.4.4. Nursing Professionalism

2.4.5. Empathy

2.4.6. Person-Centered Care Competency

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Research Variables Normal Distribution

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Measurement Model

3.4. Correlations between Variables

3.5. Testing the Structural Model

3.5.1. Verification of Fit for the Hypothetical Models

3.5.2. Hypothesis Model Test and Effect Analysis

3.5.3. Mediating Effect Analysis by Phantom Variable

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reid, C.; Courtney, M.; Anderson, D.; Hurst, C. The “caring experience”: Testing the psychometric properties of the Caring Efficacy Scale. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2015, 21, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Oh, E.G. Conceptualization of Person-Centered Care in Korean Nursing Literature: A Scoping Review. Korean J. Adult Nurs. 2020, 32, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.H. Effects of critical thinking disposition and interpersonal relationship on person centered care competency in nursing students. J. Ind. Converg. 2020, 18, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, E.Y. Development and application of person-centered nursing educational Program for Clinical Nurses. J. Digit. Converg. 2020, 18, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson Eklund, J.; Holmström, I.K.; Kumlin, T.; Kaminsky, E.; Skoglund, K.; Höglander, J.; Sundler, A.J.; Condén, E.; Meranius, M.S. ‘Same same or different?’ A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.; Choi, J.S. Attributes associated with person-centered care competence among undergraduate nursing students. Res. Nurs. Health 2020, 43, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.; Yoder, L.H. A concept analysis of person-centered care. J. Holist. Nurs. 2012, 30, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 1–360. [Google Scholar]

- Rocco, N.; Scher, K.; Basberg, B.; Yalamanchi, S.; Baker-Genaw, K. Patient-centered plan-of-care tool for improving clinical outcomes. Qual. Manag. Health Care 2011, 20, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, B.; Heo, S.; Wright, P.; Barone, C.; Rao Rettiganti, M.; Anders, M. Relationships among active listening, self-awareness, empathy, and patient-centered care in associate and baccalaureate degree nursing students. NursingPlus Open 2017, 3, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, I.; Wolf, A.; Olsson, L.E.; Taft, C.; Dudas, K.; Schaufelberger, M.; Swedberg, K. Effects of person-centred care in patients with chronic heart failure: The PCC-HF study. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1112–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCormack, B.; McCance, T.V. Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H. Factors affecting to the Person-Centered Care among Critical Care Nurses. J. Korean Crit. Care Nurs. 2020, 13, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leininger, M.M. Caring: An Essential Human Need; Wayne State University Press: Detroit, MI, USA, 1988; 157 p. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.J.; Jang, B.Y.; Yeon, J.J.; Won, P.O. The coming of the 4th industrial revolution and the HRD issues for nurses—Prospects and challenges. Korean Assoc. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2018, 21, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Factors influencing nursing students’ person-centered care. Medicina 2020, 56, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying Social Cognitive Theory of Career and Academic Interest, Choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Ko, S.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.R. Self-awareness, other-awareness and communication ability in nursing students. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2015, 21, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunn, S.V.; Burnett, P. The development of a clinical learning environment scale. J. Adv. Nurs. 1995, 22, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Han, J.Y.; Park, H.S. Effects of teaching effectiveness and clinical learning environment on clinical practice competency in nursing students. J. Korean Acad. Fundam. Nurs. 2011, 18, 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 2000, 47, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeun, E.J.; Kwon, Y.M.; Ahn, O.H. Development of a nursing professional values scale. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi 2005, 35, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comrey, A.L.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Aanalysis, 2nd ed; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 1–522. [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein, A.; Scheier, M.F.; Buss, A.H. Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1975, 43, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eun, H.G. Does Self-Regulatory Group Counseling Improve Adolescents’ Interpersonal Abilities: Self-Awareness, Other-Awareness, Interpersonal Skills and Interpersonal Satisfaction. Doctoral Dissertation, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Korea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.Y. Nursing students’ perceptions of clinical learning environment (CLE). J. Korean Data Anal. Soc. 2010, 12, 2595–2607. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.J. Development and Evaluation of the e-learning Orientation Program for Nursing Student’s Adapting to Clinical Practicum. Korean J. Adult Nurs. 2007, 19, 593–602. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Shin, Y.S. Structural model of professional socialization of nursing students with clinical practice experience. J. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 59, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Kim, M.-H.; Yung, E. Factors affecting nursing professionalism. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2008, 14, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, M.H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H. The relationship between components of empathy and prosocial behavior. Korean J. Educ. Res. 1996, 35, 143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Suhonen, R.; Gustafsson, M.L.; Katajisto, J.; Välimäki, M.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Individualized care scale—Nurse version: A Finnish validation study. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2010, 16, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Jung, K.H.; Heo, Y.H.; Woo, J.H.; Kim, K.H. How to Go through the Journal Process at Once _AMOS Structural Equation Utilization and SPSS Advanced Analysis; Hanbit Academy: Seoul, Korea, 2018; pp. 1–536. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, R.R.; Brunner, J.F. Development of a parenting alliance inventory. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1995, 24, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.C. Analysis and Application of Structural Equation Model Using SPSS/Amos; Freedom Academy: Paju, Korea, 2019; pp. 1–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, G.M.; Kim, E.; Chang, S.J. Factors affecting patient-centered nursing in regional public hospital. J. East-West Nurs. Res. 2020, 26, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.K. Person-Centered Nursing Perceived by Intensive Care Unit Nurses: Importance-Performance Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, A.; Dalgiç, A.I. It is possible to develop the professional values of nurses. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.R. Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications, and Theory; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1951; pp. 1–560. [Google Scholar]

- Derksen, F.; Olde Hartman, T.C.; van Dijk, A.; Plouvier, A.; Bensing, J.; Lagro-Janssen, A. Consequences of the presence and absence of empathy during consultations in primary care: A focus group study with patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schwind, J.K.; Beanlands, H.; Lapum, J.; Romaniuk, D.; Fredericks, S.; LeGrow, K.; Edwards, S.; McCay, E.; Crosby, J. Fostering person-centered care among nursing students: Creative pedagogical approaches to developing personal knowing. J. Nurs. Educ. 2014, 53, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugland, B.Ø.; Giske, T. Daring involvement and the importance of compulsory activities as first-year students learn person-centred care in nursing homes. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 21, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.Y. The Social Adjustment Process of Nursing Students in the Clinical Practice. J. Korean Assoc. Qual. Res. 2016, 1, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayed, A.; Malak, M.Z.; Al-amer, R.M.; Batran, A.; Salameh, B. Effect of High Fidelity Simulation on Perceptions of Self-Awareness, Empathy, and Patient-Centered Care Among University Pediatric Nursing Classes. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 56, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.B. Communication education in nursing: To promote self-awareness. Med. Commun. 2006, 1, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-García, M.C.; Gutiérrez-Puertas, L.; Granados-Gámez, G.; Aguilera-Manrique, G.; Márquez-Hernández, V.V. The connection of the clinical learning environment and supervision of nursing students with student satisfaction and future intention to work in clinical placement hospitals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Lim, Y.M. The relationship between the work environment and person-centered critical care nursing for intensive care nurses. J. Korean Crit. Care Nurs. 2019, 12, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.M.; Park, J.H. Influence of moral sensitivity and nursing practice environment in person-centered care in long-term care hospital nurses. J. Korean Gerontol. Nurs. 2018, 20, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Je, N.J.; Kim, J.S. The influence of clinical learning environment, clinical practice professionalism on caring efficacy in convergence era powerlessness, field practice adaptation, and nursing. J. Digit. Converg. 2020, 18, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.T.; Ha, Y.J.; Oh, N.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Kwon, M.J.; Lee, N.H.; Lee, Y.R.; Yang, K.H. Factors Affecting Satisfaction with Clinical Practice and Nursing Professional Values in Nursing Students. J. Korean Nurs. Res. 2018, 2, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristics/Classifications | M ± SD or N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 22.88 ± 2.05 | |

| Academic year | ||

| Third year | 151 | 39.43% |

| Fourth year | 232 | 60.57% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 338 | 88.25% |

| Male | 45 | 11.75% |

| How tuition is paid | ||

| With the help of parents | 232 | 60.57% |

| Independently | 151 | 39.43% |

| Religion | ||

| Have | 134 | 34.99% |

| None | 249 | 65.01% |

| Hospitalization experience | ||

| Experience | 180 | 47.00% |

| No Experience | 203 | 53.00% |

| Experience in caring for inpatients | ||

| Experience | 157 | 40.99% |

| No Experience | 226 | 59.01% |

| Location of university | ||

| Central Province | 79 | 20.63% |

| Honam Province | 184 | 48.04% |

| Yeongnam Province | 120 | 31.33% |

| Motivation for applying to nursing | ||

| Decided by myself | 250 | 65.28% |

| Applied according to grades | 31 | 8.09% |

| Other reasons | 102 | 26.63% |

| Subjective health status | ||

| Very healthy | 165 | 43.09% |

| Healthy | 132 | 34.46% |

| Unhealthy | 86 | 22.45% |

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-awareness | Private self-awareness | 3.49 | 0.44 | −0.21 | −0.06 |

| Public self-awareness | 3.34 | 0.43 | −0.21 | −0.06 | |

| Clinical Learning Environment | Staff–student relationship | 3.24 | 0.79 | −0.21 | −0.06 |

| Nurse manger commitment | 2.93 | 0.59 | −0.03 | 0.18 | |

| Patient relationships | 3.18 | 0.75 | −0.19 | −0.03 | |

| Student satisfaction | 3.18 | 0.66 | −0.24 | 0.50 | |

| Clinical Practicum Adaption | Nursing practice adaptation | 3.54 | 0.69 | −0.44 | 0.41 |

| Adaptation to environment | 3.30 | 0.68 | −0.03 | 0.11 | |

| Practicum satisfaction | 3.38 | 0.60 | 0.34 | 0.51 | |

| Nursing Professionalism | Self-concept of the profession | 3.89 | 0.60 | −0.38 | 0.05 |

| Role of nursing service | 4.12 | 0.75 | −1.14 | 1.37 | |

| Professionalism of nursing | 3.94 | 0.79 | −0.69 | 0.87 | |

| Empathy | Cognitive empathy | 3.63 | 0.50 | −0.11 | 0.42 |

| Affective empathy | 3.37 | 0.44 | −0.21 | 0.85 | |

| Person-Centered Care Competency | Clinical situation | 3.95 | 0.57 | −0.14 | −0.08 |

| Personal life situation | 3.68 | 0.72 | −0.02 | −0.28 | |

| Decisional control | 3.91 | 0.60 | 0.01 | −0.68 |

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | B | β | SE | CR1 | AVE | CR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-awareness | 0.53 | 0.70 | |||||

| → | Public self-awareness | 1.00 | 0.79 | ||||

| Private self-awareness | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.09 | 8.97 *** | |||

| Clinical Learning Environment | 0.61 | 0.86 | |||||

| → | Staff –student relationship | 1.00 | 0.70 | ||||

| Nurse manger commitment | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.06 | 12.70 *** | |||

| Patient relationships | 1.21 | 0.90 | 0.08 | 15.41 *** | |||

| Student satisfaction | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.07 | 14.16 *** | |||

| Clinical Practicum Adaption | 0.57 | 0.80 | |||||

| → | Nursing practice adaptation | 1.00 | 0.77 | ||||

| Adaptation to environment | 0.99 | 0.78 | 0.07 | 14.15 *** | |||

| Practicum satisfaction | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.06 | 13.21 *** | |||

| Nursing Professionalism | 0.65 | 0.85 | |||||

| → | Self-concept of the profession | 1.00 | 0.73 | ||||

| Role of nursing service | 1.38 | 0.81 | 0.09 | 14.76 *** | |||

| Professionalism of nursing | 1.60 | 0.88 | 0.10 | 15.50 *** | |||

| Empathy | 0.50 | 0.70 | |||||

| → | Cognitive empathy | 1.00 | 0.88 | ||||

| Affective empathy | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.08 | 7.25 *** | |||

| Person-centered care competency | 0.67 | 0.86 | |||||

| → | Clinical situation | 1.00 | 0.85 | ||||

| Personal life situation | 1.09 | 0.88 | 0.06 | 18.86 *** | |||

| Decisional control | 1.00 | 0.68 | 0.07 | 14.10 *** | |||

| Latent Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-awareness | 1 | |||||

| 2. Clinical Learning Environment | 0.20 | 1 | ||||

| 3. Clinical Practicum Adaption | 0.60 | 0.60 | 1 | |||

| 4. Nursing Professionalism | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 1 | ||

| 5. Empathy | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 1 | |

| 6. Person-Centered Care Competency | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 1 |

| Fitting Index | CMIN/DF | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR | NNFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | 2.73 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.07 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.91 |

| Criteria | <3 | >0.9 | >0.8 | <0.08 | >0.9 | <0.05 | >0.9 |

| Direction | B | β | SE | CR | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Gross Effect | SMC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPA | 0.645 | ||||||||

| ← | SA | 0.83 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 7.68 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.53 *** | ||

| ← | CLE | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 8.52 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.50 *** | ||

| NP | 0.347 | ||||||||

| ← | CPA | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.05 | 8.99 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.59 *** | ||

| ← | SA | 0.30 *** | 0.30 *** | ||||||

| ← | CLE | 0.31 *** | 0.31 *** | ||||||

| Empathy | 0.181 | ||||||||

| ← | SA | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 5.74 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.36 *** | ||

| ← | CLE | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 3.15 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.17 ** | ||

| PCCC | 0.388 | ||||||||

| ← | NP | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.06 | 8.22 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.49 *** | ||

| ← | Empathy | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 4.51 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.31 *** | ||

| ← | SA | 0.26 *** | 0.26 *** | ||||||

| ← | CLE | 0.20 *** | 0.20 *** | ||||||

| ← | CPA | 0.29 *** | 0.29 *** | ||||||

| Direction | Direct Effect (B) | Indirect Effect (B) | Gross Effect (B) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-awareness | → | Clinical Practicum Adaption | → | Nursing Professional Value | → | Person-Centered Care Competency | - | 0.21 *** | 0.21 *** |

| Self-awareness | → | Empathy | → | Person-Centered Care Competency | - | 0.15 *** | 0.15 *** | ||

| Clinical Learning Environment | → | Clinical Practicum Adaption | → | Nursing Professional Value | → | Person-Centered Care Competency | - | 0.12 *** | 0.12 *** |

| Clinical Learning Environment | → | Empathy | → | Person-Centered Care Competency | - | 0.04 ** | 0.04 ** | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yun, J.-Y.; Cho, I.-Y. Structural Equation Model for Developing Person-Centered Care Competency among Senior Nursing Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910421

Yun J-Y, Cho I-Y. Structural Equation Model for Developing Person-Centered Care Competency among Senior Nursing Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910421

Chicago/Turabian StyleYun, Ji-Yeong, and In-Young Cho. 2021. "Structural Equation Model for Developing Person-Centered Care Competency among Senior Nursing Students" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910421

APA StyleYun, J.-Y., & Cho, I.-Y. (2021). Structural Equation Model for Developing Person-Centered Care Competency among Senior Nursing Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910421