An Exploratory Study among Intellectual Disability Physicians on the Care and Coercion Act and the Use of Psychotropic Drugs for Challenging Behaviour

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure and Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

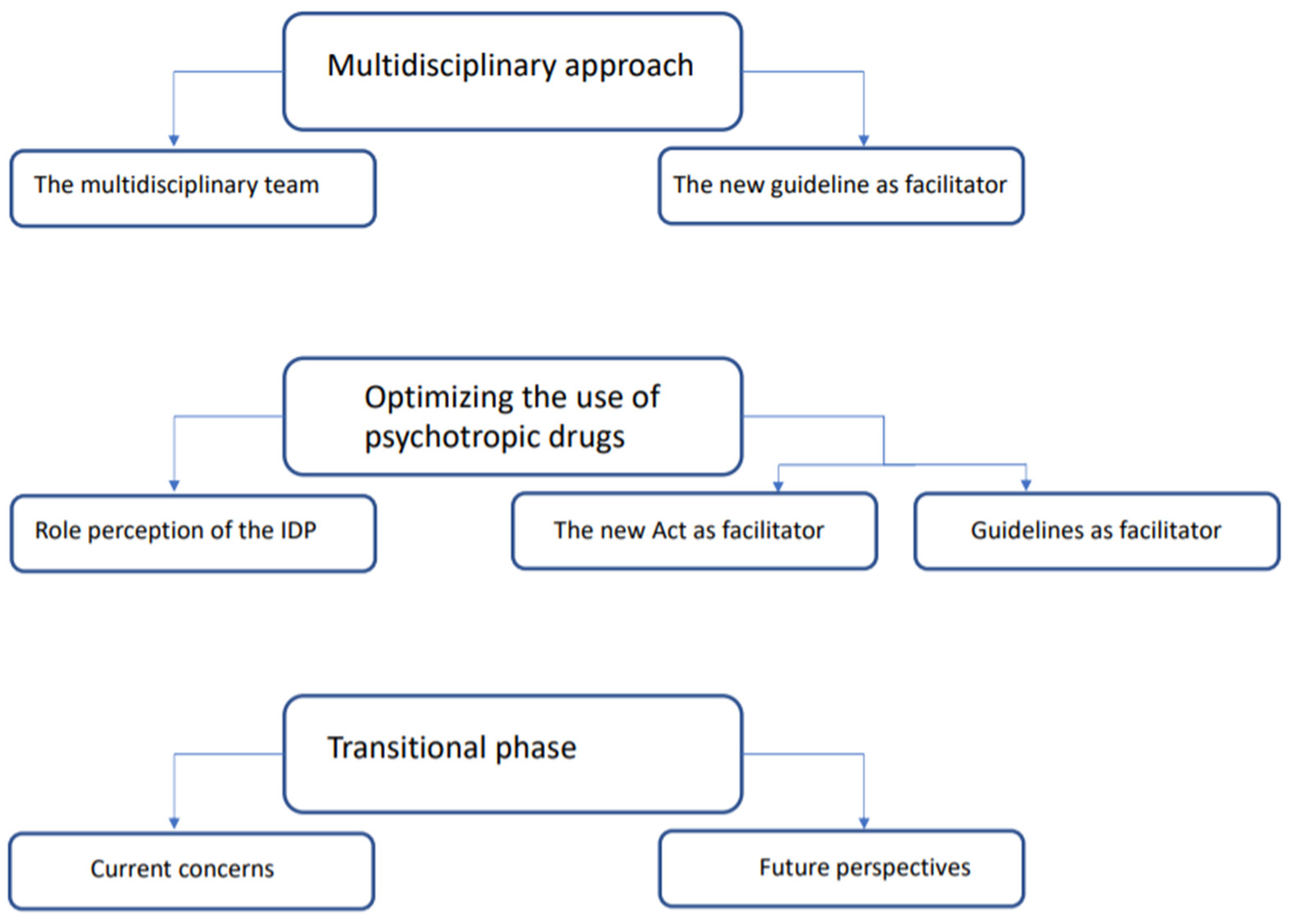

3. Results

3.1. The Multidisciplinary Approach

3.1.1. The Multidisciplinary Team

‘Challenging behaviour should never be treated by a single person, you should always do it together’ (12 years’ work experience as an IDP).

‘I do think that the psychiatrist generally knows more about the effect of psychotropic drugs in the brain. And whether or not it is safe to increase the dose’ (2 months’ work experience as an IDP).

‘Well, I would really like the cooperation with the psychiatrist to improve, the consultations being easily accessible’ (9 years’ work experience as an IDP).

3.1.2. The New Guideline as Facilitator

‘[I] thought of multidisciplinary consultation sooner and questioned the developmental psychologist more: “Do you have measurement lists or diagnostic lists for this? Could it be this and that too?” [I] questioned a little more (…) also think somewhat broader and also questioned the staff involved more’ (5 years’ work experience as an IDP).

‘[It] Really helps to professionalise the organisation, (…) the multidisciplinary approach and who does what at what time and who is responsible for something’ (7 years’ work experience as an IDP).

3.2. Optimising the Use of Psychotropic Drugs

3.2.1. Role Perception of the IDP

‘What I always do is dive into a case completely and see what has been done and what has been prescribed’ (12 years’ work experience as an IDP).

‘We as IDPs are being trained in integral thinking, not only psychotropic drugs, but also about physical complaints, the interaction between physical and mental health. And [IDPs] also better know what developmental psychologists and support workers can and should be able to do’ (7 years’ work experience as an IDP).

‘Well, I think, the thoughts about psychotropic drugs within sheltered care facilities and the idea that it can help a lot has been a continuous battle. I have been on a mission for years to explain to everybody that psychotropic drugs are for psychiatric disorders’ (8 years’ work experience as an IDP).

3.2.2. The New Act as Facilitator

‘[I] actually even reduced and stopped [the prescription], because when I looked, I Thought “what are we doing here, it may be that side effects are now the cause of the challenging behaviour, for which a measure is now being applied”’ (19 years’ work experience as an IDP).

‘Now you are being pushed into that stepped care plan and you just have to look at it more often and you may have to use a little more creative thinking and even get someone from outside to “just think along”. Maybe we are looking, are we already in such a tunnel that we overlook certain things’ (16 years’ work experience as an IDP).

3.2.3. Guidelines as Facilitators

‘I think if we want to use it, maybe we should get some sort of a maximum of three, four pages, otherwise the implementation will also be difficult’ (16 years’ work experience as an IDP).

‘Well, often I know that there is a certain diagnosis, either autism or an anxiety disorder, I take the psychiatry guidelines, because they really focus on that. And if I think of someone with addiction with no clear diagnosis, or auto mutilation for example, not much is known about it. Then I actually take the other guideline [NVAVG guideline]’ (3 years’ work experience as an IDP).

3.3. Transitional Phase

3.3.1. Current Concerns

‘There is simply a shortage of IDPs, no one has time and it [external expert role] is not something you can easily do extra, in a right way’ (…) ´Because what I now understood is mainly a paper idea of those external experts. I am afraid it will become a “paper tiger”’ (12 years’ work experience as an IDP).

‘Unfortunately, we do not yet have any agreements with other organisations [for the external expert], which should be there by now’ (2 months’ work experience as an IDP).

‘No, unfortunately not [not much known by support workers]. We agreed on an implementation process when it was published, but the person who has to do that remains anxiously silent. (…), so I am afraid that we [the organisation] will be delayed’ (2 months’ work experience as an IDP).

3.3.2. Future Perspectives

‘I do expect that we will get many more questions about psychotropic drugs. Especially when one finds out that there is actually quite a lot still off-label. (…) I do expect that there will be a huge increase in questions for our profession. (…) I don’t think so [being ready for this as a profession]’ (2 months’ work experience as an IDP).

‘And I have noticed a very big shift in recent years towards less prescription of psychotropic drugs in general. So that’s a very positive trend. (…) I really think professionalisation of care. (…) where you see that where historically psychiatrists reached for psychotropic drugs faster, IDPs do so less quickly’ (7 years’ work experience as an IDP).

‘So you are going to be even more careful about that [steps] and you will be extra tested by that external expert, first internally and then externally. So I think you can get even more careful in the end. (…) I really think that can improve the quality’ (9 years’ work experience as an IDP).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Einfeld, S.L.; Ellis, L.A.; Emerson, E. Comorbidity of intellectual disability and mental disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 36, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, M.C.; Koot, H.M.; van der Ende, J.; Verhulst, F.C. Emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with and without intellectual disability. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2002, 43, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, M.C.; Nunn, R.J.; Einfeld, S.E.; Tonge, B.J.; Koot, H.M. Assessing emotional and behavioral problems in children with intellectual disability: Revisiting the factor structure of the developmental behavior checklist. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2002, 32, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holden, B.; Gitlesen, J.P. A total population study of challenging behaviour in the county of Hedmark, Norway: Prevalence, and risk markers. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2006, 27, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerson, E.; Kiernan, C.; Alborz, A.; Reeves, D.; Mason, H.; Swarbrick, R.; Hatton, C. The prevalence of challenging behaviors: A total population study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2001, 22, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kuijper, G.M. Aspects of Long-Term Use of Antipsychotic Drugs on an Off-Label Base in Individuals with Intellectual Disability. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Matson, J.L.; Neal, D. Psychotropic medication use for challenging behaviors in persons with intellectual disabilities: An overview. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2009, 30, 572–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trollor, J.N.; Salomon, C.; Franklin, C. Prescribing psychotropic drugs to adults with an intellectual disability. Aust. Prescr. 2016, 39, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deb, S.; Kwok, H.; Bertelli, M.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Bradley, E.; Torr, J.; Guideline Development Group of the WPA Section on Psychiatry of Intellectual Disability. International guide to prescribing psychotropic medication for the management of problem behaviours in adults with intellectual disabilities. World Psychiatry 2009, 8, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, M.; Ware, R.S.; Doan, T.N.; McPherson, L.; Trollor, J.N.; Harley, D. Appropriateness of psychotropic medication use in a cohort of adolescents with intellectual disability in Queensland, Australia. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, E142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowring, D.L.; Totsika, V.; Hastings, R.P.; Toogood, S.; McMahon, M. Prevalence of psychotropic medication use and association with challenging behaviour in adults with an intellectual disability. A total population study. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2017, 61, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.; Kinnear, D.; Morrison, J.; Allen, L.; Cooper, S.-A. Psychotropic drug prescribing in a cohort of adults with intellectual disabilities in Scotland. In Proceedings of the Seattle Club Conference, Cardiff, UK, 11 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, R.; Hassiotis, A.; Walters, K.; Osborn, D.; Strydom, A.; Horsfall, C. Mental illness, challenging behaviour, and psychotropic drug prescribing in people with intellectual disability: UK population based cohort study. Br. Med. J. 2015, 351, h4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Romijn, A.; Frederiks, B.J.M. Restriction on restraints in the care for people with intellectual disabilities in the Netherlands: Lessons learned from Australia, UK, and United States. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2012, 9, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, R.; Strydom, A.; Morant, N.; Pappa, E.; Hassiotis, A. Psychotropic prescribing in people with intellectual disability and challenging behaviour. BMJ 2017, 358, j3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, N.; King, J.; Williams, K.; Hair, S. Chemical restraint of adults with intellectual disability and challenging behavior in Queensland, Australia: Views of statutory decision makers. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 24, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveau, R.; Leitch, S. Implementation of policy regarding restrictive practices in England. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 2020, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheifes, A. Psychotropic Drug Use in People with Intellectual Disability: Patterns of Use and Critical Evaluation: Patterns of Use and Critical Evaluation. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid Welzijn en Sport. Wet Zorg en Dwang. 2019. Available online: https://www.dwangindezorg.nl/wzd (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Van der Ham, B. Brief Betreffende ‘Overgangsjaar Wzd’ aan Minister de Jonge. 2019. Available online: https://www.dwangindezorg.nl/documenten/publicaties/implementatie/wzd/diversen/kamerbrief-wet-zorg-en-dwang-20-december-2019 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Ali, A.; Blickwedel, J.; Hassiotis, A. Interventions for challenging behaviour in intellectual disability. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2014, 20, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Akker, N.; Kroezen, M.; Wieland, J.; Pasma, A.; Wolkorte, R. Behavioural, psychiatric and psychosocial factors associated with aggressive behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review and narrative analysis. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 34, 327–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kuijper, G.; van den Berg, M.; Louisse, A.; Meijer, M.; Risselada, A.; Steegemans, H. Revisie NVAVG Standaard: Voorschrijven van Psychofarmaca. Available online: https://nvavg.nl/voorschrijven-van-psychofarmaca/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- De Kuijper, G.M.; Hoekstra, P.J. Physicians’ reasons not to discontinue long-term used off-label antipsychotic drugs in people with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2017, 61, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embregts, P.; Kroezen, M.; Mulder, E.J.; Van Bussel, C.; Van der Nagel, J.; Budding, M.; Busser, G.; De Kuijper, G.; Duinkerken-Van Gelderen, P.; Haasnoot, M. Multidisciplinaire Richtlijn Probleemgedrag Bij Volwassenen Met een Verstandelijke Beperking. Nederlandse Vereniging van Artsen voor Verstandelijk Gehandicapten. 2019. Available online: www.richtlijnenvg.nl (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Tournier, T.; Hendriks, A.H.; Jahoda, A.; Hastings, R.P.; Embregts, P.J. Developing a logic model for the triple-c intervention: A practice-derived intervention to support people with intellectual disability and challenging behavior. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 17, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sterkenburg, P.S.; Janssen, C.G.C.; Schuengel, C. The effect of an attachment-based behaviour therapy for children with visual and severe intellectual disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2008, 21, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boeije, H.R. Analyseren in Kwalitatief Onderzoek: Denken en Doen, 2nd ed.; Boom Koninklijke Uitgevers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Staatssecretaris van Volksgezondheid Welzijn en Sport. Kamerstuk Toekomst AWBZ, kst-30597-296. 2013. Available online: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-30597-296.html (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Embregts, P.J.C.M.; Kroezen, M.; van Bussel, C.; van Eeghen, A.; de Kuijper, G.; Lenderink, B.; Willems, A. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn ‘Probleemgedrag Bij Volwassenen Met een Verstandelijke Beperking’. Ned. Tijdschr. Voor De Zorg Aan Mensen Met Verstand. Beperkingen (NTZ) 2020, 2–9. Available online: https://nvavg.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Richtlijn-Probleemgedrag-bij-volwassenen-met-een-VB-DEF.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Bloemendaal, I.; Leemkolk, B.; van de Noordzij, E. Werkcontext en Tijdsbesteding van de Arts Verstandelijk Gehandicapten. Herhaalmeting 2018; Prismant: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; Available online: https://capaciteitsorgaan.nl/app/uploads/2019/10/Prismant-2019-Werkcontext-en-tijdsbesteding-van-de-AVG-herhaalmeting-2018-def.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

bij de Weg, J.C.; Honingh, A.K.; Teeuw, M.; Sterkenburg, P.S. An Exploratory Study among Intellectual Disability Physicians on the Care and Coercion Act and the Use of Psychotropic Drugs for Challenging Behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910240

bij de Weg JC, Honingh AK, Teeuw M, Sterkenburg PS. An Exploratory Study among Intellectual Disability Physicians on the Care and Coercion Act and the Use of Psychotropic Drugs for Challenging Behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910240

Chicago/Turabian Stylebij de Weg, Janouk C., Aline K. Honingh, Marieke Teeuw, and Paula S. Sterkenburg. 2021. "An Exploratory Study among Intellectual Disability Physicians on the Care and Coercion Act and the Use of Psychotropic Drugs for Challenging Behaviour" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910240

APA Stylebij de Weg, J. C., Honingh, A. K., Teeuw, M., & Sterkenburg, P. S. (2021). An Exploratory Study among Intellectual Disability Physicians on the Care and Coercion Act and the Use of Psychotropic Drugs for Challenging Behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910240