Public Health Impacts of Underemployment and Unemployment in the United States: Exploring Perceptions, Gaps and Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Interviews

3. Results

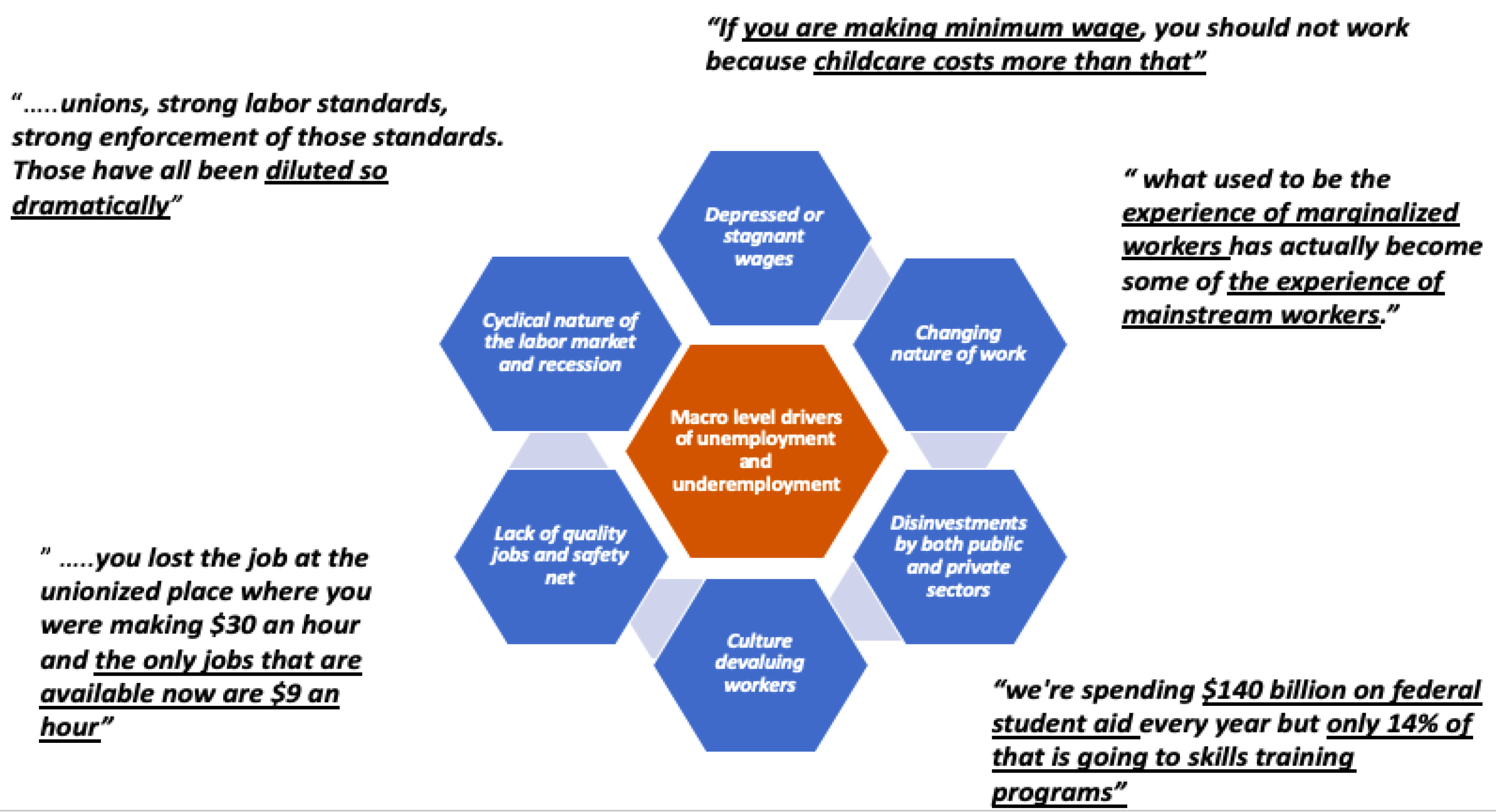

3.1. Large Macro-Level Issues Are Driving the Underemployment and Unemployment Narrative

“All of the things that gives power to workers……like unions, strong labor standards, strong enforcement of those standards. Those have all been diluted so dramatically…”—interview respondent from a policy group.

“you lost the job at the unionized place where you were making USD 30 an hour and the only jobs that are available now are USD 9 an hour. It’s just like totally and utterly demoralizing and catastrophic at every level. […]…… where are those other good jobs you can find when you lost a job…[…]… one of the things that made it so bad for so many people is they can’t find another one that can sustain their living standards”—interview respondent from a workforce development organization.

“what used to be the experience of marginalized workers (for whatever reason they were marginalized) has actually become some of the experience of mainstream workers”—interview respondent from a workforce development organization.

“Employers have no investment in their workers. They’re not the employer of record anymore […]…they have every incentive in the world to outsource their work. So, it doesn’t matter if you’re blue collar, white collar or even university professors. […]……work is constantly being non-standardized”—interview respondent from a worker advocacy group.

“the jobs aren’t particularly good. I just don’t know people who are like, “Oh, I’m dying to be in retail.”… the growth in terms of number of jobs…it is in the services, it is in hospitality, retail, education services, and the occupations that grow the most are the lowest paid. I think the wages thing is totally key. We have the employer, who in this country has a lot of power to keep wages down. And they do exercise that power”—interview respondent from a policy group.

“I think that the story is a lot less about workers not having the right skills. I’m not saying that skills are not important but a huge share of jobs in this country require no training or maybe some high school ……[…]… look at BLS data…and the astounding number of jobs that just don’t actually require that many specific skills. And the difference between what is a good job and not a good job are unions and labor standards. …[…]… is a bigger player than the skills story…”—interview respondent from a policy group.

“we are not targeting that federal or private investment in workers who need it in order to progress along their career pathway. …[…]… we are spending USD 140 billion on federal student aid every year but only 14% of that is going to skills training programs, there’s a mismatch between what people are experiencing, and what people want to be doing and what we’re actually spending money on”—interview respondent from a skills coalition group.

3.2. Gaps Exist in the Definitions and Measures of Underemployment and Unemployment

“…there are many ways to measure unemployment and there’s the standard rate that gets reported in the mainstream media every month. A lot of people think the more accurate analysis of the strength of the economy is the employment to population ratio ……And we are actually lower by historical standard in the employment to population ratio. Another standard is for people who are still unemployed (long-term unemployment)…[…]…usually post-recession in a recovery the length of long-term unemployment starts to shorten and that hasn’t been happening”—interview respondent from a policy group.

“unemployment is at 3.5 percent. …..the overall numbers have enormous variation…….and enormously different outcomes for different individuals and different groups. Like the demographics and certain classes of workers. And the racial/minority unemployment rate is almost vastly different … essentially the black unemployment rates is twice the white unemployment ratings this time or that time”—interview respondent from a workforce development organization.

“unemployment rate…is a kind of a marker that people are familiar with. For those of us in the field, we know that […] marker that people talk about globally is actually not a full picture. So that number doesn’t necessarily encompass all the folks out there who aren’t working. …we just need to make sure that people understand that”—interview respondent from a policy group.

“Underemployment for me is really just about folks that are working in subpar economic scenarios……underemployment could also then be defined as working multiple jobs to barely make it, or working multiple jobs to make it… but being underemployed in each of those areas makes it more difficult to participate say fully in family or whatever the circle of peoples experience is…”—interview respondent from a community colleges system.

3.3. Need for Quality Data on Health Outcomes for Individuals and Communities by Demographics and Geographic Levels; and for Connecting Health Data to Policy Makers, Workforce Development Agencies, Employers and Funders

3.3.1. Extensive Empirical Literature on Impacts of Unemployment (Mostly Long Term) on Physical, Mental Health and Psychological Well-Being

3.3.2. Limited Research on Impacts of Underemployment on Physical, Mental and Psychological Well-Being

3.3.3. Organizations do not Routinely Consider Health Outcomes as They Relate to Their Work in Workforce Development, Policy Development or in Programs Addressing Underemployment and Unemployment

“We don’t have any kind of connections to the health impact of a worker of not having a job. That’s not a lens that we look at”—interview respondent from industry.

“Unfortunately, the link between unemployment and health and how unemployment might cause ill health is really not something that we’ve done any work on ourselves. It’s a little bit peripheral to what we have typically looked at but I agree that we should better understand what the health impacts are”—interview respondent from a policy group.

“So much of your identity is tied up in what you do for a living and how you take care of your family that I think that mental health is a natural impact of unemployment and we as a field don’t have a good way of dealing with that”—interview respondent from a workforce development organization.

“People don’t sleep because they work back to back jobs. People use all sorts of stimulants, everything from drinking lots of soda and pop to other substances to keep going when they have to work multiple jobs………..I think you have issues of people’s security when you have to really think about how you manage your childcare when you’re working third shift and there’s no third shift childcare in this country. But just the running at 200% all the time, sort of no sleep, the precariousness of that has effects on people’s health”—interview respondent from a worker advocacy group.

“I think one of the things that we do poorly as a system is address the health needs of—again, we meet people where they’re at. Often when we meet them, they are having health problems often related to the thing we’re trying to help them with. And we don’t have a good way of dealing with that”—interview respondent from a workforce development organization.

3.4. Other Challenges Expressed by Stakeholders

3.4.1. Lack of a Common Agenda and Aligned Goals of Multiple Stakeholders Creates a Burden for All in Accomplishing Goals

“…one of the things I’ve struggled with…is there’s so many different nonprofit groups out there……depending on who you talk to within government, everybody has their own pet project or their own organization that they have an allegiance to or a connection to”—interview respondent from industry.

“everybody has to have their own program at the federal level, and there are 2000 competing programs out there. And we’ve made it so hard to navigate the system”—interview respondent from a skills coalition group.

“As far as things boosting labor standards and enforcement and unionization… those things have really honestly faced no support from (Congress) … It’s been sort of a both-sides-of-the-aisle are problematic.”—interview respondent from a policy group

3.4.2. Current Workforce Development and Education Systems Lack the Coordination and Scale Needed to Support the 21st Century US Workforce

“The US invests at lower rates than every other industrialized country in workforce programming limitations…[…]… funding for the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), our public workforce system, has declined 40% since 2001”—interview respondent from a skills coalition group.

“…[…]… there are far more people that have a college degree than we have jobs that require a college degree”—interview respondent from a policy group.

“Not just giving businesses tax breaks but what does that mean about developing the infrastructure that this industry needs to survive…. the workforce being one of them? …..[…]… we don’t have industrial policy, we don’t have any kind of workforce strategy at all.[…]….we have built these best practices into policy like demand driven, sector driven, employer driven. But that’s still very individualized and neoliberal”—interview respondent from a workforce development organization.

“The role of industry and sector partnerships at a local level, these local communities of stakeholders, of local businesses, of community and technical colleges, and community-based organizations, of TANF agencies of the different folks that are interacting with and serving workers and employers is really how workforce development can be done really well. There’s good data on the fact that sectoral approaches have been successful in leading to employment and earnings outcomes. But these are the kind of partnerships that are difficult to support and difficult to sustain without federal or state investment in doing so”—interview respondent from a skills coalition group.

3.4.3. Need for Strong Public Policies and Programs to Ensure Stability, upward Mobility, and Health Equity

“(When it comes to childcare) how people make it work is beyond me. I don’t understand as a society how we have not figured out how to not make this a burden on individuals because it crosses race lines, it crosses class lines. So, definitely childcare, in particular for women who are on the low spectrum of the income bracket, it’s make it or break it…if you are a logical, rational person and you are making minimum wage, you should not work because childcare costs more than what—let’s just do the numbers, right?”—interview respondent from a workforce development organization.

“There is also a gap in planning and understanding and thinking about what the social needs are and then carrying schooling and training to fulfill those needs. And that has to be a partnership, not just between private sector but also public sector because all that has to be paid for”—interview respondent from a skills coalition group.

4. Discussion

4.1. Underemployment and Unemployment Are Symptoms of Larger Problems

4.2. Gaps in Data and Research Will Need to Be Addressed in Order to Realize the Full Magnitude and Impact of Underemployment and Unemployment

4.3. Need for Strategic Funding to Foster Scaling-Up and Translation of Successful Models of Initiatives and Partnerships between Employers–Educators, Employers–Workforce Development, Labor Management–Advocacy in Workforce Development, Education, Research and Policy

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

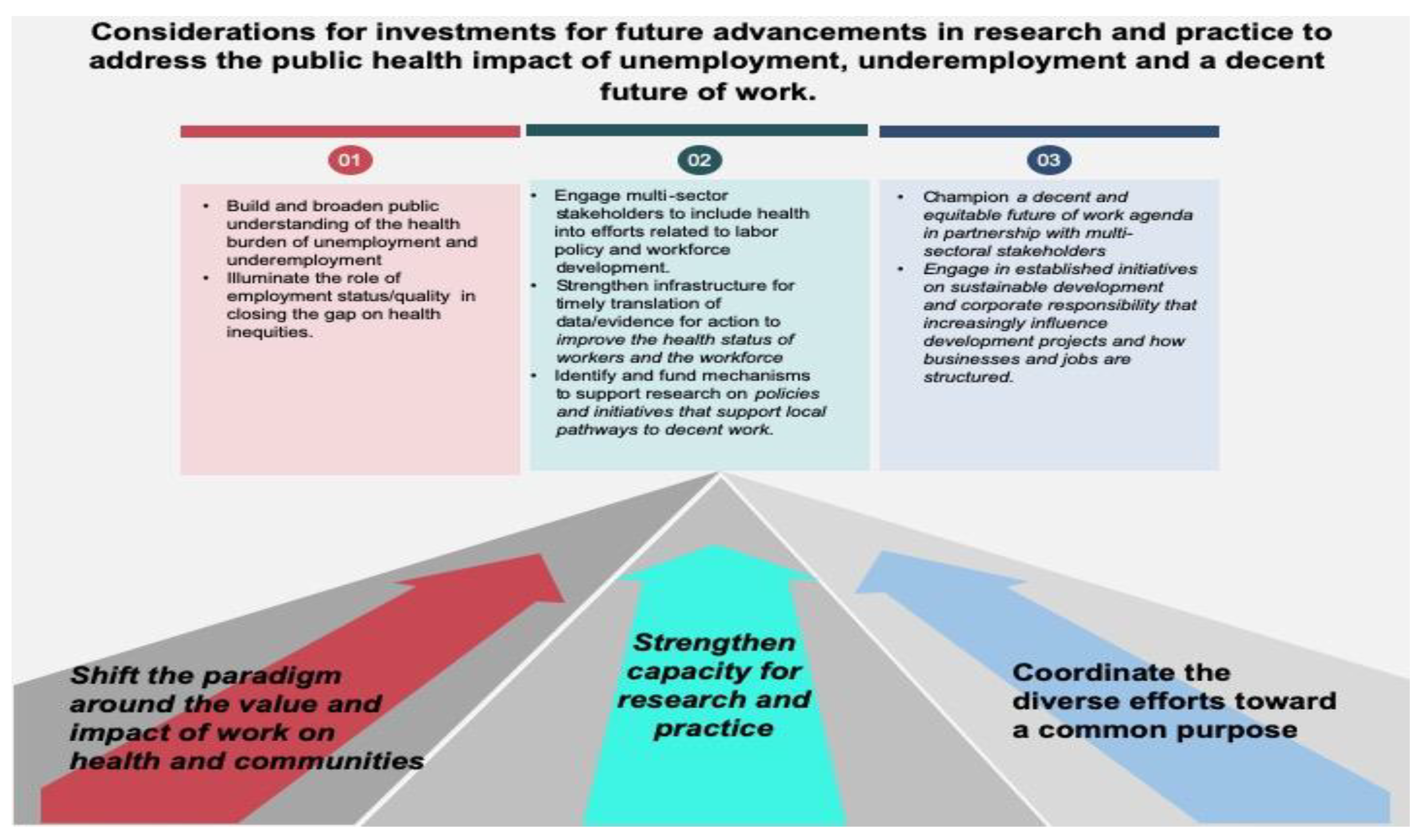

- Shift the paradigm around the value of work and its impact on individual health and communities, by investing in broadening public understanding of the health burden of underemployment and unemployment. As researchers and practitioners in the field of occupational health, we understand that although social determinants of health (SDoH) “are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age”, what people do for work and at work does not figure in larger discussions related to SDoH [128]. Despite the conceptual acknowledgment that work influences health through numerous pathways, it remains largely absent from examinations of health inequities in the United States [123]. Public health needs to illuminate the role of employment quality and status in closing the gap on health inequities.

- Strengthen capacity for research and practice by engaging the multisector stakeholders that public health may not routinely engage with, such as workforce development, labor policy, and corporate sustainability. Inclusion of health into efforts related to labor policy development and other economic development agendas can add value to discussions regarding the burden of the problem on health and the healthcare system, economic investments in skills training and social benefits, and improve the health status of workers and the workforce [124]. Strengthening infrastructure for timely use of data/evidence for action in labor policy and workforce development could ensure the jobs they create are designed to contribute to healthier workers and communities. New funding mechanisms are also needed to support practice-based research partnerships that address institutional and systems-level facilitators and barriers to the innovation and implementation of policies and initiatives in order to support local pathways to decent work.

- Coordinate the diverse efforts in the work ecosystem towards a common purpose and a shared agenda for a decent future of work. Currently, diverse agendas and potential misalignment of multiple stakeholders, the overall complexity of the problem, a lack of metrics and actionable data, and a lack of leadership and a common language are limiting the ability of stakeholders in the work ecosystem to collectively address the impact of underemployment and unemployment, and assess the future of work more generally [8]. Under the public health model, increasing the number and quality of jobs can serve as a prevention strategy by increasing economic security, self-esteem, and social connectedness. “Public Health 3.0 A Call to Action for Public Health to Meet the Challenges of the 21st Century” [135] refers to a new era of enhanced and broadened public health practice that goes beyond traditional public health department/agencies functions and programs. Cross sectoral collaboration is inherent in Public Health 3.0. As such, labor policy that is a part of health policy, and a discussion of job quality or decent work, not just job quantity, could help public health professionals engage in more established initiatives on sustainable development and corporate responsibility that increasingly influence development projects and how businesses and jobs are structured [124]. Public health needs to champion an agenda in partnership with multisector stakeholders to integrate workforce health and well-being into labor and economic development agendas across government agencies and industry.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McKinsey Global Institute. The Future of Work after COVID-19. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/the-future-of-work-after-covid-19 (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Siqueira, C.E.; Gaydos, M.; Monforton, C.; Slatin, C.; Borkowski, L.; Dooley, P.; Liebman, A.; Rosenberg, E.; Shor, G.; Keifer, M. Effects of social, economic, and labor policies on occupational health disparities. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013, 57, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, S. The Social Consequences of Insecure Jobs. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 93, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Is job insecurity on the increase in OECD countries? In Employment Outlook; OECD: Paris, France, 1997; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/2080463.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Taking the measure of temporary employment. In Employment Outlook; OECD: Paris, France, 2002; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/emp/17652675.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Weil, D. The Fissured Workplace; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, L.; Carroll-Scott, A.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Santilli, A.; Ickovics, J.R. The importance of full-time work for urban adults’ mental and physical health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1692–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamers, S.L.; Streit, J.; Pana-Cryan, R.; Ray, T.; Syron, L.; Ma, M.A.F.; Castillo, D.; Roth, G.; Geraci, C.; Guerin, R.; et al. Envisioning the future of work to safeguard the safety, health, and well-being of the workforce: A perspective from the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2020, 63, 1065–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, P.A.; Streit, J.M.K.; Sheriff, F.; Delclos, G.; Felknor, S.A.; Tamers, S.L.; Fendinger, S.; Grosch, J.; Sala, R. Potential Scenarios and Hazards in the Work of the Future: A Systematic Review of the Peer-Reviewed and Gray Literatures. Ann. Work. Expo. Health 2020, 64, 786–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambra, C. Yesterday once more? Unemployment and health in the 21st century. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2010, 64, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, M.; Ferrie, J. Do we need to worry about the health effects of unemployment? J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2009, 64, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, A.; Deaton, A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15078–15083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, R.E.; Thompson, N.J. Unemployment and Depression among Emerging Adults in 12 States, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2010. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athar, H.M.; Chang, M.H.; Hahn, R.A.; Walker, E.; Yoon, P.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Unemployment-United States, 2006 and 2010. MMWR Suppl. 2013, 62, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Venkataramani, A.S.; Bair, E.F.; O’Brien, R.L.; Tsai, A.C. Association between Automotive Assembly Plant Closures and Opioid Overdose Mortality in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. Updated Estimates and Analysis. Third Edition. 2020. Available online: http://oit.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_743146.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- International Labour Organization. ILO Policy Brief on COVID-19: A Policy Framework for Tackling the Economic and Social Impacts of the COVID-19 Crisis. May 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_745337.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Faghri, P.D.; Dobson, M.; Landsbergis, P.; Schnall, P.L. COVID-19 Pandemic: What Has Work Got to Do with It? J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, e245–e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Employment Situation April 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Brookings Institution. Race and Jobs at Risk of Being Automated in the Age of COVID-19. 2021. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/research/race-and-jobs-at-risk-of-being-automated-in-the-age-of-covid-19/ (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surgeon General’s Call to Action: Community Health and Prosperity. 2018. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/09/06/2018-19313/surgeon-generals-call-to-action-community-health-and-prosperity (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Ezzy, D. Unemployment and mental health: A critical review. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993, 37, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P.B. Work, Unemployment, and Mental Health; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Friedland, D.S.; Price, R.H. Underemployment: Consequences for the Health and Well-Being of Workers. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2003, 32, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaton, B. Life Transitions, Role Histories, and Mental Health. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1990, 55, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R.L. Work and Health; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, D.; Prause, J. Underemployment as disguised unemployment and its social costs. In Proceedings of the APA-NIOSH Interdisciplinary Conference on Work, Stress, and Health: Organization of Work in a Global Economy, Baltimore, MA, USA, 11–13 March 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dollard, M.F.; Winefield, A.H. Mental health: Overemployment, underemployment, unemployment and healthy jobs. Aust. E-J. Adv. Ment. Health 2002, 1, 170–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragher, E.B.; Cass, M.; Cooper, C. The relationship between job satisfaction and health: A meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 62, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragher, E.B.; Cass, M.; Cooper, C.L. The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Health: A Meta-Analysis. In From Stress to Wellbeing; Cooper, C.L., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Decent Work, Report of the Director-Genera. In Proceedings of the 87th Session, International Labour Conference, Geneva, Switzerland; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/P/09605/09605(1999-87).pdf (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- International Labour Organization. ILO Implementation Plan 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development 2016. 2016. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---webdev/documents/publication/wcms_510122.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Jalles d’Orey, M.A.; How Do Donors Support the Decent Work Agenda? A Review of Five Donors. Overseas Development Institute. 2017. Available online: https://www.ituc-csi.org/IMG/pdf/oda_decent_work_en.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Williams, B.; Van‘t Hof, S. Wicked Solutions: A Systems Approach to Complex Problems. 2014. Available online: http://www.bobwilliams.co.nz/ewExternalFiles/Wicked.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday/Currency: New York, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rowel, R.; Moore, N.D.; Nowrojee, S.; Memiah, P.; Bronner, Y. The utility of the environmental scan for public health practice: Lessons from an urban program to increase cancer screening. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2005, 97, 527–534. [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley, P. Qualitative Data Analysis: Practical Strategies; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasmeier, A.K. Living Wage Calculator. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2020. Available online: Livingwage.mit.edu (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Howard, J. Nonstandard work arrangements and worker health and safety. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2016, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, M.; Bohle, P. Contingent work and occupational safety. In The Psychology of Workplace Safety; Barling, J., Frone, M.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, R.; Tausig, M. The Macroeconomic Context of Job Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1994, 35, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, H.L. Underemployment, Unemployment, and Mental Health. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 476. 2012, pp. 17–18. Available online: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/476 (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Ferman, L.; Gordus, J. Mental Health and the Economy; Ferman, L., Gordus, J., Eds.; UpJohn Institute: Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 1979; pp. 193–224. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, L. Still Falling Short on Hours and Pay: Part-Time Work Becoming New Normal. 2016. Available online: https://www.epi.org/files/pdf/114028.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Bell, D.N.F.; Blanchflower, D.G. Underemployment in the US and Europe. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 24927. 2018. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w24927 (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Minimum Wage by State. 2021. Available online: http://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/state-minimum-wage-chart.aspx (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Narain, K.D.C.; Zimmerman, F.J. Examining the association of changes in minimum wage with health across race/ethnicity and gender in the United States. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertner, A.K.; Rotter, J.S.; Shafer, P. Association between State Minimum Wages and Suicide Rates in the USA. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehby, G.L.; Dave, D.M.; Kaestner, R. Effects of the minimum wage on infant health. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2020, 39, 411–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibragimov, U.; Beane, S.; Friedman, S.R.; Komro, K.; Adimora, A.A.; Edwards, J.K.; Williams, L.D.; Tempalski, B.; Livingston, M.D.; Stall, R.D.; et al. States with higher minimum wages have lower STI rates among women: Results of an ecological study of 66 US metropolitan areas, 2003–2015. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, K. Is Skill Mismatch Impeding U.S. Economic Recovery. ILR Rev. 2015, 68, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelli, P. Skills Gap, Skills Shortages and Skills Mismatches: Evidence and Arguments for the US. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 20382. 2014. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w20382 (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Lazear, E.P.; Spletzer, J.R. The United States Labor Market: Status Quo or a New Normal? National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 18386. 2012. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w18386 (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Rothstein, J. The Labor Market Four Years into the Crisis: Assessing Structural Explanations. ILR Rev. 2012, 65, 467–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, A.D.; Manzo, F.; Bruno, R. A Manufactured Myth: Why Claims of a “Skills Gap” in Illinois Manufacturing are Wrong. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Labor Education Program Briefing Papers. 2013. Available online: https://live-labor-edu.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/LEP-Briefing-Paper-Skills-Gap_-Dickson-Manzo-Bruno.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Accenture, Burning Glass Technologies, & Harvard Business School. Bridge the Gap: Rebuilding America’s Middle Skills. 2014. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/competitiveness/Documents/bridge-the-gap.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Adecco USA. The Skills Gap and the State of the Economy [Blog Post]. 2013. Available online: http://blog.adeccousa.com/the-skills-gap-and-the-state-of-the-economy/ (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- ManpowerGroup. Skilled Trades Remain Hardest Job to Fill in US for Fourth Consecutive Year. 2013. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/manpowergroup-annual-talent-shortage-survey-reveals-us-employers-making-strides-to-build-sustainable-workforces-report-less-difficulty-filling-open-positions-209129591.html (accessed on 28 May 2013).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Full Employment: An Assumption within BLS Projections. 2017. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/full-employment-an-assumption-within-bls-projections.htm (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Employment Situation December 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_01102020.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Feldman, D.C. The nature, antecedents and consequences of underemployment. J. Manag. 1996, 22, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee-Ryan, F.; Harvey, J. I Have a Job, But A Review of Underemployment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 962–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.W.; Shea, T.H.; Sikora, D.M.; Perrewé, P.L.; Ferris, G.R. Rethinking underemployment and overqualification in organizations: The not so ugly truth. Bus. Horizons 2012, 56, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobe, D. US Unemployment Improves in October. Gallup. 2011. Available online: http://www.gallup.com/poll/150527/Unemployment-Improves-October.aspx (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Newport, F.; Muller, G. In US, Underemployment Lowest in North Dakota, Wyoming. Gallup. 2011. Available online: http://www.gallup.com/poll/146486/Underemployment-Lowest-North-Dakota-Wyoming.aspx (accessed on 4 March 2011).

- Jensen, L.; Slack, T. Underemployment in America: Measurement and Evidence. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2003, 32, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Levin, A.T. Labor Market Slack and Monetary Policy. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 21094. 2015. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w21094 (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- De Anda, R.M. Unemployment and Underemployment among Mexican-Origin Workers. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1994, 16, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, G.F.; Madamba, A.B. A Double Disadvantage? Minority Group, Immigrant Status, and Underemployment in the United States. Soc. Sci. Q. 2001, 82, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltero, J.M. Inequality in the Workplace: Underemployment among Mexicans, African-Americans, and Whites; Garland: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M. Underemployment and economic disparities among minority groups. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 1993, 12, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valletta, R.G.; Bengali, L.; van der List, C. Cyclical and Market Determinants of Involuntary Part-Time Employment. Working Paper No. 2015-19. 2018. Available online: http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/2015/19/ (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Mutchler, J.F. Underemployment and Gender: Demographic and Structural Indicators. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, M.A.; Cunningham, T.R.; Guerin, R.J.; Keller, B.; Chapman, L.J.; Hudson, D.; Salgado, C.; Cincinnati, O.H.; National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, American Society of Safety Engineers (NIOSH/ASSE). Overlapping vulnerabilities: The Occupational Safety and Health of Young Workers in Small Construction Firms. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2015-178. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277213891_Overlapping_vulnerabilities_the_occupational_safety_and_health_of_young_workers_in_small_construction_firms (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Gravel, S.; Dubé, J. Occupational health and safety for workers in precarious job situations: Combating inequalities in the workplace. E-J. Int. Comp. Labour Stud. 2016, 5, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kasl, S.V.; Jones, B.A. Unemployment and health. In Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine; Ayers, S., Baum, A., McManus, C., Newman, S., Wallston, K., Weinman, J., West, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, K.; Moser, K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Griffiths, R.F.; Gavin, M.B. Time structure and unemployment: A longitudinal investigation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1997, 70, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, A.; Lundberg, I.; Hallsten, L.; Ottosson, J.; Hemmingsson, T. Unemployment and mortality—A longitudinal prospective study on selection and causation in 49321 Swedish middle-aged men. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2009, 64, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagozdzon, P.; Zaborski, L.; Ejsmont, J. Survival and cause-specific mortality among unemployed individuals in Poland during economic transition. J. Public Health 2008, 31, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Åhs, A.M.; Westerling, R. Mortality in relation to employment status during different levels of unemployment. Scand. J. Public Health 2006, 34, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdtham, U.-G.; Johannesson, M. A note on the effect of unemployment on mortality. J. Health Econ. 2003, 22, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.; Cook, D.; Shaper, A.G. Loss of employment and mortality. BMJ 1994, 308, 1135–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefansson, C.-G. Long-term unemployment and mortality in Sweden, 1980–1986. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martikainen, P. Unemployment and mortality among Finnish men, 1981–1985. BMJ 1990, 301, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, L.; Sabroe, S.; Damsgaard, M.T. Hospital admissions before and after shipyard closure. BMJ 1989, 299, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iversen, L.; Andersen, O.; Andersen, P.K.; Christoffersen, K.; Keiding, N. Unemployment and mortality in Denmark, 1970–1980. BMJ 1987, 295, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, K.A.; Fox, A.J.; Jones, D.R. Unemployment and mortality in the OPCS Longitudinal Study. Lancet 1994, 2, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.M.; Jackson, P.R. Golden parachutes: Changing the experience of unemployment for managers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reininghaus, U.A.; Morgan, C.; Simpson, J.; Dazzan, P.; Morgan, K.; Doody, G.A.; Bhugra, D.; Leff, J.; Jones, P.; Murray, R.; et al. Unemployment, social isolation, achievement–expectation mismatch and psychosis: Findings from the AESOP Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, N.; Karniol, R. The sense of self-continuity as a resource in adaptive coping with job loss. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broman, C.L.; Hamilton, V.L.; Hoffman, W.S.; Mavaddat, R. Race, gender, and the response to stress: Autoworkers’ vulnerability to long-term unemployment. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 1995, 23, 813–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarström, A. Health consequences of youth unemployment. Public Health 1994, 108, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarstrom, A. Early unemployment can contribute to adult health problems: Results from a longitudinal study of school leavers. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2002, 56, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossakowski, K.N. Is the duration of poverty and unemployment a risk factor for heavy drinking? Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.W.; Balluz, L.S.; Ford, E.S.; Giles, W.H.; Strine, T.W.; Moriarty, D.G.; Croft, J.B.; Mokdad, A.H. Associations Between Short- and Long-Term Unemployment and Frequent Mental Distress Among a National Sample of Men and Women. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 45, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, D.; Catalano, R. Do economic variables generate psychological problems? Different methods, different answers. In Economic psychology: Intersections in Theory and Application; MacFadyen, A.J., MacFadyen, H.W., Eds.; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1986; pp. 503–546. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, F.; Florence, C.S.; Quispe-Agnoli, M.; Ouyang, L.; Crosby, A.E. Impact of Business Cycles on US Suicide Rates, 1928–2007. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee-Ryan, F.; Song, Z.; Wanberg, C.R.; Kinicki, A.J. Psychological and Physical Well-Being During Unemployment: A Meta-Analytic Study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanberg, C.R. The Individual Experience of Unemployment. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galambos, N.L.; Barker, E.T.; Krahn, H.J. Depression, self-esteem, and anger in emerging adulthood: Seven-year trajectories. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 42, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moller, H. Health Effects of Unemployment. Wirral Performance & Public Health Intelligence Team. 2012. Available online: https://www.wirralintelligenceservice.org/media/1086/unemployment-2-sept-12.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Bartley, M. Accumulated labour market disadvantage and limiting long-term illness: Data from the 1971–1991 Office for National Statistics’ Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 31, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefft, N.; Kageleiry, A. State-Level Unemployment and the Utilization of Preventive Medical Services. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 49, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.E. A conceptual formulation for research on stress. In Social and Psychological Factors in Stress; McGrath, J.E., Ed.; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D.N.; Blanchflower, D.G. The well-being of the overemployed and the underemployed and the rise in depression in the UK. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2019, 161, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Johnson, G. Underemployment, underpayment, and psychosocial stress among working Black men. West. J. Black Stud. 1989, 13, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Wooden, M.; Warren, D.; Drago, R. Working Time Mismatch and Subjective Well-being. Br. J. Ind. Relations 2009, 47, 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, R. The Consequences of Underemployment for the Underemployed. J. Ind. Relations 2007, 49, 247–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prause, J.; Dooley, D. Effect of underemployment on school-leavers self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 1997, 20, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooley, D.; Prause, J. Underemployment and alcohol abuse in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. J. Stud. Alcohol 1998, 59, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulfgramm, M. Life satisfaction effects of unemployment in Europe: The moderating influence of labour market policy. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2014, 24, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voßemer, J.; Gebel, M.; Täht, K.; Unt, M.; Högberg, B.; Strandh, M. The Effects of Unemployment and Insecure Jobs on Well-Being and Health: The Moderating Role of Labor Market Policies. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 138, 1229–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandh, M.; Strandh, M.; Strandh, M.; Strandh, M. State Intervention and Mental Well-being among the Unemployed. J. Soc. Policy 2001, 30, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundert, S.; Hohendanner, C. Active Labour Market Policies and Social Integration in Germany: Do ‘One-Euro-Jobs’ Improve Individuals’ Sense of Social Integration? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 31, 780–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, M.; Mooney, A. Unemployment and health in the context of economic change. Soc. Sci. Med. 1983, 17, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, T.; Greene, A.; Hunter, D.; McKee, L.; Elliott, E.; Harrington, B.; Marks, L.; Williams, G. Performance assessment and wicked problems: The case of health inequalities. Public Policy Adm. 2006, 21, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, J. Wicked problems and social complexity. In Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems; Dans Conklin, J., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- JPMorgan Chase &Co. Skills Gap: A National Issue That Requires Regional Focus. New Skills at Work Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.economicmodeling.com/wp-content/uploads/EMSI-SkillsGap-Brief.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Ison, R. Systems Practice: How to Act. In Situations of Uncertainty and Complexity in a Climate-Change World, 2nd ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahonen, E.Q.; Fujishiro, K.; Cunningham, T.; Flynn, M. Work as an Inclusive Part of Population Health Inequities Research and Prevention. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, M.A.; Wickramage, K. Leveraging the domain of work to improve migrant health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, M.A. Immigration, Work, and Health: Anthropology and the Occupational Health of Labor Immigrants. Anthro-Pology Work. Rev. 2018, 39, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckham, T.K.; Baker, M.G.; Camp, J.E.; Kaufman, J.D.; Seixas, N.S. Creating a Future for Occupational Health. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2017, 61, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, M.A.; Carreón, T.; Eggerth, D.E.; Johnson, A.I. Immigration, Work, and Health: A Literature Review of Immigration Between Mexico and the United States. Rev. de Trab. Soc. 2014, 6, 129–149. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. In Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Employment Conditions Knowledge Network of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. In Employment Conditions and Health Inequalities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Benach, J.; Muntaner, C. Precarious employment and health: Developing a research agenda. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2007, 61, 276–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranford, C.J.; Vosko, L.F.; Zukewich, N. Precarious employment in the canadian labour market: A statistical portrait. Just Labour 1969, 3, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosko, L.F.; Zukewich, N.; Cranford, C. Beyond Non-standard Work: A New Typology of Employment. Perspect. Labour Income 2003, 4, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, P.A.; Cunningham, T.R.; Nickels, L.; Felknor, S.; Guerin, R.; Blosser, F.; Chang, C.-C.; Check, P.; Eggerth, D.; Flynn, M.; et al. Translation research in occupational safety and health: A proposed framework. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coburn, C.E.; Penuel, W.R.; Geil, K.E. Research-Practice Partnerships: A Strategy for Leveraging Research for Educational Improvement in School Districts; William, T., Ed.; Grant Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health 3.0. A Call to Action to Create a 21st Century Public Health Infrastructure. 2016. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/Public-Health-3.0-White-Paper.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2019).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pratap, P.; Dickson, A.; Love, M.; Zanoni, J.; Donato, C.; Flynn, M.A.; Schulte, P.A. Public Health Impacts of Underemployment and Unemployment in the United States: Exploring Perceptions, Gaps and Opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910021

Pratap P, Dickson A, Love M, Zanoni J, Donato C, Flynn MA, Schulte PA. Public Health Impacts of Underemployment and Unemployment in the United States: Exploring Perceptions, Gaps and Opportunities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910021

Chicago/Turabian StylePratap, Preethi, Alison Dickson, Marsha Love, Joe Zanoni, Caitlin Donato, Michael A. Flynn, and Paul A. Schulte. 2021. "Public Health Impacts of Underemployment and Unemployment in the United States: Exploring Perceptions, Gaps and Opportunities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910021

APA StylePratap, P., Dickson, A., Love, M., Zanoni, J., Donato, C., Flynn, M. A., & Schulte, P. A. (2021). Public Health Impacts of Underemployment and Unemployment in the United States: Exploring Perceptions, Gaps and Opportunities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10021. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910021