Facilitators and Barriers to Physical Activity and Sport Participation Experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Adults: A Mixed Method Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

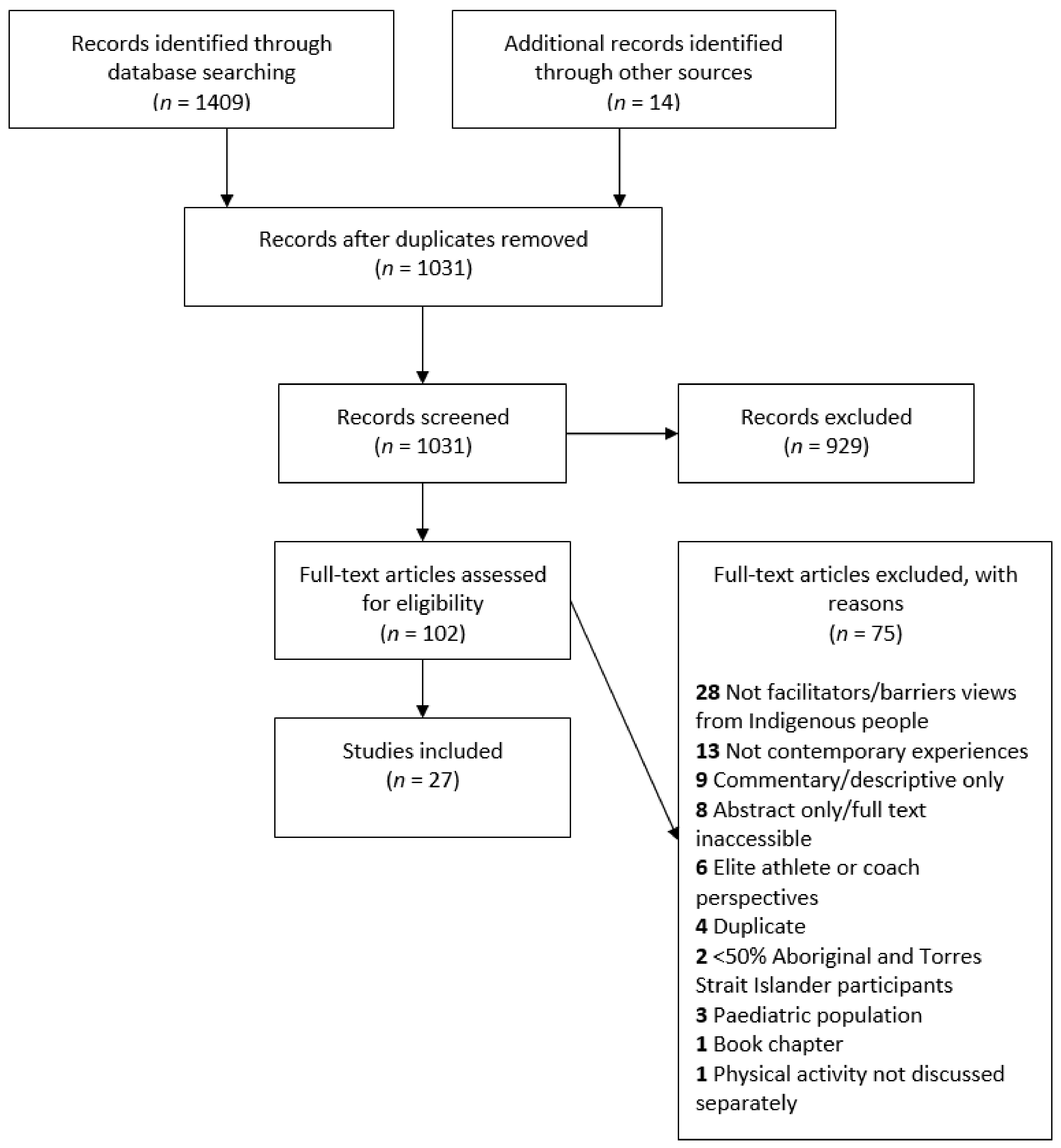

2. Materials and Methods

Critical Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Study Inclusion

3.2. Methodological Quality

3.3. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.4. Findings of the Review

| Reference (Author, Date) | Aim | Design | Program/ Context | Data Collection Methods | Data Analysis | Theoretical Framework/Epistemology | Type of Physical Activity or Sport | State and Geographic Context | Participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | Sex | Age (years) | |||||||||

| Andrews 2013 [34] | Evaluate an Aboriginal health & wellbeing intervention | Participatory action research, photovoice, semi-structured interviews, focus groups | Weekly free physical activities, healthy meal & “yarn” led by Aboriginal sports association | Interviews and focus groups, written notes | Thematic analysis | Not specified | Structured physical activity program: Zumba | WA Urban | n = 13 | M: 3 F: 10 | 25–75 |

| Canuto 2013 [39] | Identify perceived barriers & facilitators to attendance of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander women | Qualitative: individual semi-structured interviews | Cohort from pragmatic randomised control trial of a physical activity and nutritional education program | Interviews | Thematic network analysis | Chen’s program planning framework and socio-ecological frameworks (First Nations adapted) | Structured twice weekly exercise class | SA Urban | n = 16 | F | 18–64 |

| Caperchione 2009 [40] | To report the barriers, challenges and enablers to physical activity participation in priority women’s groups | Focus groups | Community walking groups | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Inductive thematic analysis | Not specified | General, walking groups | VIC, NSW, QLD Urban Rural | 3 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander focus groups | F | Not clear |

| Carr 2019 [35] | To explore perspectives of individuals and family on “what is important” and “what works best” to keep people with cerebellar ataxia walking and moving around | First Nations and participatory methodology, semi-structured interviews | N/A | Interviews and transcribed field notes | Inductive thematic analysis | Constructivist grounded theory | Walking and general | NT Remote | n = 12 | M: 4 F: 8 | 30+ |

| Cavanagh 2015 [54] | To identify impact of sport and active recreation programs on health, attitudes and behaviours, social connectedness, and sense of belongingness | Semi-structured individual interviews and Yarning circles | Pilot sport and recreation program combined with healthy eating program | Manually collected interview data | Thematic content analysis | Sarason’s framework of belongingness | Sports, recreational exercise | Not specified Remote | n = 9 | M | Not clear |

| Davey 2014 [53] | To report on participation and effectiveness of a combined cardio-vascular and pulmonary rehabilitation and secondary prevention program | Qualitative: participant evaluation survey | 8-week cardiopulmonary rehabilitation program, with bi-weekly exercise sessions and weekly educational sessions | Evaluation forms completed by participants at end of program | Iterative thematic analysis | Not specified | Rehabilitative exercise program | TAS Urban | n = 51 | M, F | 18+ |

| David 2018 [18] | To find out the health benefit of self-initiated On-Country activities | Qualitative: participatory methods, oral conversations | N/A | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | On-Country activities | NT Remote | Not specified | F | Not clear |

| Hunt 2008 [42] | To explore the meaning of, barriers to, and potential strategies to promote physical activity participation | Focus groups | N/A | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Iterative, thematic analysis | Not specified | General | QLD Urban | n = 96 | M: 45 F: 51 | 18+ |

| Lin 2012 [37] | To gain an in-depth understanding of chronic lower back pain experience | In-depth semi-structured informal interviews using Yarning | N/A | Recorded and transcribed interviews, additional data: field observation and notes from informal yarns | “Describe-compare-relate” process | Qualitative interpretive framework | General | WA Rural Remote | n = 32 | M: 21 F: 11 | 26–72 |

| Macdonald 2012 [43] | To examine discourse of lifestyle recruited to normalise living standards of Indigenous Australians, particularly women & girls | From larger study: semi-structured and open interviews with families, field notes and document collection | Cross-organizational network efforts to decrease diabetes through increasing recreational physical activity opportunities | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Iterative thematic analysis | Postcolonial critique | General | QLD Remote | 21 families | F | Not clear |

| Macniven 2020 [49] | To identify exercise motivators, barriers, habits and environment | First Nations or “Indigenist” research methods, online survey | N/A | Online survey through survey monkey | Descriptive statistics with difference testing by Indigenous status | Not specified | Exercise | NSW Urban | n = 167 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander n = 45 | M: 28 F: 17 | 18–64 |

| Macniven 2018 [36] | To examine perceptions of the health and community impact of the Indigenous Marathon Program on Thursday Island | (a) Qualitative: semi-structured interviews (b) Quantitative: questionnaire | Indigenous Marathon Program: annually a squad of 12 young Indigenous adults aged 18–30 are selected to train to run a marathon while living in community | Recorded and transcribed interviews, paper questionnaire | (a) Thematic content analysis. (b) Descriptive statistics with difference testing by Indigenous status | Not specified | Running | QLD Remote | (a) n = 18 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander n = 14 (b) n = 104 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander n = 43 | (b) M: 13 F: 29 | 18+ |

| Maxwell 2019 [50] | To explore how digital health technologies contribution to Indigenous Australian women’s increased participation in physical activity | Qualitative: digital tracking and diarizing of activity levels for 8 weeks, focus groups/Yarning circles, individual interviews | Individualised self-designed health and activity goals, digitally tracked activity levels for 8 weeks | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Typological analysis | Not specified | Leisure activities | NSW Urban Rural | n = 8 | F | 18+ |

| Mellor 2016 [41] | To record views on factors that contribute to poor physical health | Participatory action framework, focus groups, individual interviews | N/A | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Iterative analysis | Health belief model | General | VIC, WA Urban Rural Remote | n = 150 | M | 18–35 |

| Nalatu 2012 [32] | To understand the physical activity needs and experiences of post-natal women | Follow-up case studies, in-depth interviews | N/A | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Thematic analysis | Theory of planned behaviour | General | QLD Urban | n = 27 total n = 10 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | F | 24–32 |

| Nelson2016 [44] | To explore client and staff perception of the Work It Out program | Semi-structured small group or individual interviews | Chronic disease self-management and rehabilitation program: education session and tailored exercise session 2–4 times/week, optional individual meetings with allied health professionals | Transcribed interviews | Thematic analysis | Constructionism and Most Significant Change theory | Structured exercise program | QLD Urban | n = 22 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander n = 16 | M, F | 21–77 |

| Parmenter 2020 [45] | To explore perceptions of the factors that influence their participation in rehabilitation program | Focus groups using Yarning, strengths-based approach | 12-week cycle with twice weekly Yarning (education) and tailored supervised exercise | Recorded and transcribed focus groups | Inductive analysis | Not specified | Structured exercise program | QLD Urban | n = 102 | M: 43 F: 59 | 18–80 |

| Peloquin 2017 [46] | To determine regionally-based Indigenous Australian adults barriers or facilitators to PA, compared to regionally-based non-Indigenous Australians | Individual interviews | N/A | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Thematic analysis | Phenomenology | General | QLD Rural/ regional | n = 24 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander n = 12 | M: 5 F: 7 | 18–55 |

| Seear 2019 [52] | Identify how and why some Aboriginal people have made positive lifestyle changes | Individual interviews using Yarning | N/A | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Thematic analysis | Phenomonology | General | WA Remote | n = 4 | M | 20–35 |

| (i) Stronach 2015 [31] (ii) Stronach 2018 [30] (iii) Stronach 2019 [29] | (i) To explore meaning, place and experience of sport & physical activity to Indigenous women, their needs and wants, and contribution to their health and well-being. ( ii) To explore sporting experiences and community strengths of Indigenous women (iii) To consider significance of swimming for Aboriginal women | Dadirri methodology, group or individual interviews using a “conversation approach” | N/A | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Inductive and deductive thematic analysis guided by Dadirri methodology | (i) Bourdieu’s social theory (ii) Empowerment (iii) Not specified | Sport and physical activity, swimming | NSW, TAS Urban Remote | n = 22 | F | 18–74 |

| Sushames 2017 [47] | To explore barriers and enablers to participation in a community-tailored physical activity intervention | Semi-structured individual interviews | 8-week free physical activity program | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Thematic analysis | Health belief model | Structured physical activity program | QLD Rural/ regional | n = 12 | M, F | 18–45 |

| Thompson 2013 [51] | To explore local perspectives, experiences and meanings of physical activity | Participatory action research, semi-structured individual interviews,additional data sources: 5 local paintings and field observations | N/A | Recording and transcription of interviews, field observations recorded in journal | Thematic analysis of interviews and paintings | Not specified | General | NT Remote | n = 23 | M: 9 F: 14 | 16–65 |

| Thorpe 2014 [38] | To examine barriers and motivators for participation in Aboriginal community sporting team | Focus groups, semi-structured individual interviews | N/A | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Qualitative analysis | Grounded theory | Football | VIC Urban | n = 14 | Not clear | Not clear |

| Walker 2020 [48] | To explore meaning of being healthy and how social media influences health behaviours | Face-to-face or online group semi-structured interviews informal Yarning with participant by phone or in person prior to interview | N/A | Recorded and transcribed interviews | Thematic analysis | Integrated model of behaviour change theory | General | VIC Urban Rural | n = 18 | M: 9 F: 9 | 17–24 |

| Young 2018 [33] | To research sports participation and physical activity behaviour and its context, patterns and drivers | Focus groups, in-depth individual interviews | N/A | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | General | NT, SA, QLD, VIC, ACT, NSW Urban Rural Remote | 38 focus groups 32 in-depth interviews | M, F | 18+ |

3.5. Individual Facilitators and Barriers

3.6. Interpersonal Facilitators and Barriers

3.7. Community and Environment Facilitators and Barriers

3.8. Policy and Program Facilitators and Barriers

| Socio-Ecological Level | Urban | Regional/Rural | Remote | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | Barriers | Facilitators | Barriers | Facilitators | Barriers | |

| Individual | Health problems/desire to prevent disease progression [39] Expected benefit [33,42] Practical need, i.e., active transport [33] Desire to improve fitness [38,49] Enjoyment [38,39,53] Personal experience of injury or illness [41] Knowledge of First Nations health issues and risk factors [41] Digital health trackers and increased self-awareness of activity levels [50] Relieve stress, mental wellbeing [38] Self-motivation [32,39,49] Curiosity [39] Desire to support research [39] Poor body image perceptions [32] Feeling healthier/improved health [39,44,53] Learning new health information [53] Self-stereotype as natural athlete [31] Physical activity integrated into culture and daily life [31] | Lack of access to transport and logistical difficulty [33,34,39,41] Lack of self-motivation [32,33,49,50] Financial constraints [31,32,33,39,41,42] Lack of time [33,49,50] Injury or illness [33,34,42,45,49] Disability [42] Work commitments [33,34,39,50] Lack of resources [38] Study commitments [39,50] Challenges with digital health tracker technology [50] Other commitments [39] Major life events [39] Lack of confidence to try something new [44] General attitude to health and exercise [44] Pain from exercising the previous day [49] | Health problems/desire to prevent disease progression [47] Expected benefit [33] Practical need, i.e., active transport [33] Desire to improve fitness [47] Personal experience of injury or illness [41] Knowledge of First Nations health issues and risk factors [41] Digital health trackers and increased self-awareness of activity levels [50] | Lack of access to transport and logistical difficulty [33,41,46,47] Lack of self-motivation [33,50] Financial constraints [33,41,47] Lack of time [33,50] Injury or illness [33,37] Disability [37] Work commitments [33,47,50] Unemployment [47] Travelling for other reasons [47] Menstruation [47] Study commitments [50] Challenges with digital health tracker technology [50] | Health problems/desire to prevent disease progression [35,36,51] Expected benefit [33] Practical need, i.e., active transport [33,51] Desire to improve fitness [36] Enjoyment [36] Personal experience of injury or illness [41] Knowledge of First Nations health issues and risk factors [36,41] Weight control [36,51] Making small, slow behaviour changes [52] Relieve stress, mental wellbeing [36] Having a purpose [35,54] Assistive devices and home modifications [35] Modifying activities [35] Feeling internally strong/happy [35] Self-stereotype as natural athlete [31] Physical activity integrated into culture and daily life [31] | Lack of access to transport and logistical difficulty [31,33,54] Lack of self-motivation [33,36] Financial constraints [31,33,41] Lack of time [33] Injury or illness [33,37] Disability [35,37] Work commitments [33] Poor mental health [35] Lack of resources [18] Difficulty changing long-term behaviour [52] Perceived age or weight constraints [36] |

| Interpersonal | Peer support [38,53] Family support including material/instrumental support [39] Influence of role models [34,48] Influence of family [44,48] Influence of friends [48] Program staff support, respect, encouragement [39,45] Role-modelling for children [32] Inclusion of families in activities [38,42] Competition [38,50] Information sharing on social media [48] Group activities and exercise companions [42,45,53] Social connections [31,32,34,38,39] Challenging racism [38] Participation of others from community network [53] Positive/supportive group atmosphere [39,45] Women-only groups [29] | Cultural obligations including funerals [45] Racism [31,33,38,41] Family commitments including caring for children [31,33,39,42,45,49,50] Shame and embarrassment [33] Prioritising children’s participation [33] Gender roles and responsibilities [32] Lack of peer support [32] Peer rivalry [38] Lack of social interaction [50] Community/family conflict [34,38] Conflict with program staff [34] Public judgement [42] | Peer support [47] Family support including material/instrumental support [46,47] Influence of role models [48] Influence of family [46,48] Influence of friends [48] Program staff support, respect, encouragement [47] Role-modelling for children [46] Inclusion of families in activities [47] Competition [50] Information sharing on social media [48] Group activities and exercise companions [46] Role model/program leader of same gender [47] | Cultural obligations including funerals and Sorry Business [47] Racism [33,41] Family commitments including caring for children [33,46,50] Shame and embarrassment [33,47] Prioritising children’s participation [33] Lack of family support [47] Lack of peer support [47] Stigma around physical activity [47] Lack of social interaction [50] Non-Indigenous group atmosphere [46] | Peer support [52] Family support including material/instrumental support [35,52] Influence of role models [36] Influence of family [36] Influence of friends [36] Program staff support, respect, encouragement [36] Role-modelling for others [30,31] Social connections [31,54] | Cultural obligations including funerals [18] Racism [31,33,41] Family commitments including caring for children [31,33,43] Shame and embarrassment [33,35,36,43] Prioritising children’s participation [33] Gender roles and responsibilities [43] Families not included [54] Safety concerns for elderly [18] |

| Community | Community health behaviour, attitudes [48] Cultural activities [40] Culturally appropriate/ culturally safe environment [31,39,49] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific facility or activity [41] History and pride [38] Access to equipment [53] Community connections [38] | Culturally inappropriate activities/lack of cultural inclusiveness [33] Lack of available services/physical activity opportunities [31,33,42] General safety concerns [42] Unsafe or inadequate infrastructure [31,32] Weather and climate [32] Traffic [39] Urban setting [42] Disrupted connection with culture and land [41] Community expectations [38] High community death rates [34] | Community health behaviour, attitudes [48] Cultural activities [40] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific facility or activity [41] | Culturally inappropriate activities/lack of cultural inclusiveness [33] Lack of available services/physical activity opportunities [33] General safety concerns [46] Unsafe or inadequate infrastructure [46] Unfriendly and uncomfortable neighbourhood [46] Lack of access to facilities [47] Disrupted connection with culture and land [29] | Community health behaviour, attitudes [36] Cultural activities [35,51] Culturally appropriate/culturally safe environment [31] Appealing and varied locations for activity [36] Community connections [36] | Culturally inappropriate activities/lack of cultural inclusiveness [33,51] Lack of available services/physical activity opportunities [31,33] General safety concerns [36] Unsafe or inadequate infrastructure [31,36] Weather and climate [18] Dangerous dogs [36] Unappealing outstations [18] Distractions of community life [18] |

| Program and Policy | Free program [31,39,45] Supportive employers [34] Provision of transport [45,53] Structured program [53] Positive program experience [39] Convenient times and location [39] Provision of childcare [39] Program meets needs and expectations [39] Professionalism/ well-organised program [39] Program connected to local Aboriginal community-controlled health organisation [45] Flexibility [45] Variety of exercises in program [53] | Inconvenient program location [39] Program different to expectations, mismatched with fitness level [39] Lack of sustainable, local physical activity programs [42] Insufficient number of programs and locations [44] Lack of motivation, confidence of initiative around chronic disease self-management [44] Lack of knowledge about programs [44] | Free program [47] | Session times and frequency [47] | Support from services [35] | No one to run program [54] Session times and frequency [54] Loss of program funding [54] Lack of sustainable, local physical activity programs [43] Reliance on welfare [43] |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Mandated Areas: Environment. n.d. [cited 2020 Nov 24]. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/mandated-areas1/environment.html#:~:text=Indigenous%20peoples%20account%20for%20most,as%205%2C000%20different%20indigenous%20cultures (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Brass, G. Addressing global health disparities among Indigenous peoples. Lancet 2016, 388, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, P.; Cormack, D.; Paine, S.J. Colonial histories, racism and health—The experience of Māori and Indigenous peoples. Public Health 2019, 172, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carson, B.D.T.; Chenhall, R.D.; Bailie, R. (Eds.) Social Determinants of Indigenous Health; Allen and Unwin: Crows Nest, NSW, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, T.W.; Lawrence, C.; Wadley, G. Designing for diversity in Aboriginal Australia: Insights from a national technology project. In Proceedings of the 31st Australian Conference on Human-Computer-Interaction, Fremantle, WA, Australia, 2–5 December 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 418–422. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework (HPF) Report 2017; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yaman, F. The Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, 2011. Public Health Res. Pract. 2017, 27, e2741732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thompson, S.C.; Haynes, E.; Woods, J.A.; Bessarab, D.C.; Dimer, L.A.; Wood, M.M.; Sanfilippo, F.M.; Hamilton, S.J.; Katzenellenbogen, J.M. Improving cardiovascular outcomes among Aboriginal Australians: Lessons from research for primary care. SAGE Open Med. 2016, 4, 2050312116681224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sushames, A.; van Uffelen, J.G.; Gebel, K. Do physical activity interventions in Indigenous people in Australia and New Zealand improve activity levels and health outcomes? A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macniven, R.; Canuto, K.; Wilson, R.; Bauman, A.; Evans, J. The impact of physical activity and sport on social outcomes among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: A systematic scoping review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2019, 22, 1232–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach-Mortensen, A.M.; Verboom, B. Barriers and facilitators systematic reviews in health: A methodological review and recommendations for reviewers. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions; Atkins, L., West, R., Eds.; Silverback Publishing: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Pot, N.; Keizer, R. Physical activity and sport participation: A systematic review of the impact of fatherhood. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelly, S.; Martin, S.; Kuhn, I.; Cowan, A.; Brayne, C.; Lafortune, L. Barriers and Facilitators to the Uptake and Maintenance of Healthy Behaviours by People at Mid-Life: A Rapid Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, E.; Stavreski, B.; Jennings, G.L.; Kingwell, B.A. Exploring Motivation and Barriers to Physical Activity among Active and Inactive Australian Adults. Sports 2017, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, V.; Hughes, C.; Thornton, L.; Squibb, K.; Venn, A.; Ball, K. Environmental barriers and enablers to physical activity participation among rural adults: A qualitative study. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2015, 26, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- David, G.; Wilson, R.; Yantarrnga, J.; von Hippel, W.; Shannon, C.; Willis, J. Health Benefits of Going On-Country; The Lowitja Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea, K. Traditional Diet and Food Preferences of Australian Aboriginal Hunter-Gatherers [and Discussion]. Philos. Trans. Biol. Sci. 1991, 334, 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- May, T.; Dudley, A.; Charles, J.; Kennedy, K.; Mantilla, A.; McGillivray, J.; Wheeler, K.; Elston, H.; Rinehart, N.J. Barriers and facilitators of sport and physical activity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and adolescents: A mixed studies systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A.; Abbott, R.; Macdonald, D. Indigenous Australians and physical activity: Using a social–ecological model to review the literature. Health Educ. Res. 2010, 25, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aromataris, E.M.Z. (Ed.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. [cited 2020 July 15]. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Macniven, R.; Canuto, K.J.; Evans, J.R. Facilitators and barriers to physical activity participation experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults: A mixed methods systematic review protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2021, 19, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Information: Melbourne, Australia, 2014.

- Stern, C.; Lizarondo, L.; Carrier, J.; Godfrey, C.; Rieger, K.; Salmond, S.; Apostolo, J.; Kirkpatrick, P.; Loveday, H. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2108–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, R.; Pluye, P.; Bartlett, G.; Macaulay, A.C.; Salsberg, J.; Jagosh, J.; Seller, R. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfield, S.; Pearson, O.; Morey, K.; Kite, E.; Canuto, K.; Glover, K.; Gomersall, J.S.; Carter, D.; Davy, C.; Aromataris, E.; et al. Assessing the quality of health research from an Indigenous perspective: The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal tool. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stronach, M.; Adair, D.; Maxwell, H. ‘Djabooly-djabooly: Why don’t they swim?’: The ebb and flow of water in the lives of Australian Aboriginal women. Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 22, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronach, M.; Maxwell, H.; Pearce, S. Indigenous Australian women promoting health through sport. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 22, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronach, M.; Maxwell, H.; Taylor, T. ‘Sistas’ and Aunties: Sport, physical activity, and Indigenous Australian women. Ann. Leis. Res. 2015, 19, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalatu, S. Understanding the Physical Activity Patterns of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mothers, Including the Factors that Influence Participation; Griffith University: Nathan, QLD, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Young, C.W.A.; Sproston, K. Indigenous Australians’ Participation in Sports and Physical Activities: Part 2, Qualitative Research (National Report); ORC International for the Australian Sports Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Y. An Urban Aboriginal Health and Wellbeing Program: Participant Perceptions; The University of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, J.J.; Lalara, J.; Lalara, G.; O’Hare, G.; Massey, L.; Kenny, N.; Pope, K.E.; Clough, A.R.; Lowell, A.; Barker, R.N. ‘Staying strong on the inside and outside’ to keep walking and moving around: Perspectives from Aboriginal people with Machado Joseph Disease and their families from the Groote Eylandt Archipelago, Australia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macniven, R.; Plater, S.; Canuto, K.; Dickson, M.; Gwynn, J.; Bauman, A.; Richards, J. The “ripple effect”: Health and community perceptions of the Indigenous Marathon Program on Thursday Island in the Torres Strait, Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2018, 29, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, I.B.; O’Sullivan, P.B.; Coffin, J.A.; Mak, D.B.; Toussaint, L.; Straker, L.M. ‘I am absolutely shattered’: The impact of chronic low back pain on Australian Aboriginal people. Eur. J. Pain 2012, 16, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, A.; Anders, W.; Rowley, K. The community network: An Aboriginal community football club bringing people together. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2014, 20, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canuto, K.J.; Spagnoletti, B.; McDermott, R.A.; Cargo, M. Factors influencing attendance in a structured physical activity program for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in an urban setting: A mixed methods process evaluation. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caperchoine, C.; Mummery, W.K.; Joyner, K. Addressing the challenges, barriers, and enablers to physical activity participation in priority women’s groups. J. Phys. Act. Health 2009, 6, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.; McCabe, M.; Ricciardelli, L.; Mussap, A.; Tyler, M. Toward an Understanding of the Poor Health Status of Indigenous Australian Men. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.; Marshall, A.L.; Jenkins, D. Exploring the meaning of, the barriers to and potential strategies for promoting physical activity among urban Indigenous Australians. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2008, 19, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.; Abbott, R.; Jenkins, D. Physical Activity of Remote Indigenous Australian Women: A Postcolonial Analysis of Lifestyle. Leis. Sci. 2012, 34, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, A.; Mills, K.; Dargan, S.; Roder, C. “I Am Getting Healthier” Perceptions of Urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People in a Chronic Disease Self-Management and Rehabilitation Program. Health 2016, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parmenter, J.; Basit, T.; Nelson, A.; Crawford, E.; Kitter, B. Chronic disease self-management programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: Factors influencing participation in an urban setting. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 31, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péloquin, C.; Doering, T.; Alley, S.; Rebar, A. The facilitators and barriers of physical activity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander regional sport participants. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushames, A.; Engelberg, T.; Gebel, K. Perceived barriers and enablers to participation in a community-tailored physical activity program with Indigenous Australians in a regional and rural setting: A qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, T.; Molenaar, A.; Palermo, C. Aqualitative study exploring what it means to be healthy for young Indigenous Australians and the role of social media in influencing health behaviour. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2021, 32, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macniven, R.; Esgin, T. Exercise motivators, barriers, habits and environment at an Indigenous community facility. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, H.; O’Shea, M.; Stronach, M.; Pearce, S. Empowerment through digital health trackers: An exploration of Indigenous Australian women and physical activity in leisure settings. Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 24, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.L.; Chenhall, R.D.; Brimblecombe, J.K. Indigenous perspectives on active living in remote Australia: A qualitative exploration of the socio-cultural link between health, the environment and economics. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seear, K.H.; Lelievre, M.P.; Atkinson, D.N.; Marley, J.V. ‘It’s Important to Make Changes.’ Insights about Motivators and Enablers of Healthy Lifestyle Modification from Young Aboriginal Men in Western Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davey, M.; Moore, W.; Walters, J. Tasmanian Aborigines step up to health: Evaluation of a cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and secondary prevention program. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cavanagh, J.; Southcombe, A.; Bartram, T.; Hoye, R. The impact of sport and active recreation programs in an Indigenous men’s shed. J. Aust. Indig. Issues 2015, 18, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bessarab, D.; Ng’andu, B. Yarning About Yarning as a Legitimate Method in Indigenous Research. Int. J. Crit. Indig. Stud. 2010, 3, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- West, R.; Stewart, L.; Foster, K.; Usher, K. Through a Critical Lens: Indigenist Research and the Dadirri Method. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, K. Understanding the Australian Aboriginal experience of collective, historical and intergenerational trauma. Int. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 1522–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.J.; Dale, M.J.; Niyonsenga, T.; Taylor, A.W.; Daniel., M. Associations between area socioeconomic status, individual mental health, physical activity, diet and change in cardiometabolic risk amongst a cohort of Australian adults: A longitudinal path analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233793. [Google Scholar]

- Macniven, R.; Richards, J.; Gubhaju, L.; Joshy, G.; Bauman, A.; Banks, E.; Eades, S. Physical activity, healthy lifestyle behaviors, neighborhood environment characteristics and social support among Australian Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal adults. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macniven, R.; Elwell, M.; Ride, K.; Bauman, A.; Richards, J. A snapshot of physical activity programs targeting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2017, 28, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowitja Institute. We Nurture Our Culture for Our Future, and Our Culture Nurtures Us: Close the Gap; Lowitja Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, C.P.; Johnston, F.H.; Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Whitehead, P.J. Healthy Country: Healthy People? Exploring the health benefits of Indigenous natural resource management. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2005, 29, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, R.; Thurber, K.A.; Wright, A.; Chapman, J.; Donohoe, P.; Davis, V.; Lovett, R. Associations between Participation in a Ranger Program and Health and Wellbeing Outcomes among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People in Central Australia: A Proof of Concept Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennie, A.; Marlin, D.; Apoifis, N.; White, R.L. ‘We were made to feel comfortable and safe’: Co-creating, delivering, and evaluating coach education and health promotion workshops with Aboriginal Australian peoples. Ann. Leis. Res. 2021, 24, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, D. Ancestral footprints: Assumptions of ‘natural’ athleticism among Indigenous Australians. J. Aust. Indig. Issues 2012, 15, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifian, F. Cultural Conceptualisations in English Words: A Study of Aboriginal Children in Perth. Lang. Educ. 2005, 19, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Evans, J.; Macniven, R. Long term trends in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth sport participation 2005–2019. Ann. Leis. Res. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 Edition; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, South Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kilanowski, J.F. Breadth of the Socio-Ecological Model. J. Agromedicine 2017, 22, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, C.; Mays, N. Qualitative Research: Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: An introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ 1995, 311, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.; Macniven, R.; Thomson, N. Review of Physical Activity among Indigenous People; Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet: Perth, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Socio-Ecological Level | Facilitators | Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Self-beliefs and attitudes Poor body image perceptions [32] Self-motivation [32,39,49] Curiosity [39] Desire to support research [39] Self-stereotype as natural athlete [31] Digital health trackers and increased self-awareness of activity levels [50] Physical activity aligned with daily life Physical activity integrated into culture and daily life [31] Practical need, i.e., active transport [33,51] Expected and realised benefits Expected benefit [33,49] Enjoyment [36,38,39,53] Having a purpose [35,54] Feeling healthier/improved health [39,44,53] Health goals and issues Desire to improve fitness [36,38,47,49] Relieve stress, mental wellbeing [36,38] Knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health issues and risk factors [36,41] Personal experience of injury or illness [41] Learning new health information [53] Health problems/desire to prevent disease progression [35,36,39,47,51] Weight control [36,51] Feeling internally strong/happy [35] Overcoming specific challenges Making small, slow behaviour changes [52] Assistive devices and home modifications [35] Modifying activities [35] | Self-beliefs and attitudes Lack of self-motivation [32,33,36,49,50] Lack of confidence to try something new [44] General attitude to health and exercise [44] Challenges with digital health tracker technology [50] Personal circumstances Lack of access to transport and logistical difficulty [31,33,34,39,41,46,47,54] Financial constraints [31,32,33,39,41,42,46,47] Unemployment [47] Lack of time [33,49,50] Lack of resources [18,38] Work commitments [33,34,39,47,50] Study commitments [39,50] Other commitments [39] Travelling for other reasons [47] Major life events [39] Health goals and issues Injury or illness [33,34,37,42,45,49] Poor mental health [35] Menstruation [47] Pain from exercising the previous day [49] Other specific challenges Difficulty changing long-term behaviour [52] Disability [35,37,42] Perceived age or weight constraints [36] |

| Interpersonal | Having an impact and being impacted by others Influence of role models [34,36,48] Role model/program leader of same gender [47] Influence of family [36,44,46,48] Influence of friends [36,48] Role-modelling for children [32,46] Role-modelling for others [30,31] Information sharing on social media [48] Challenging racism [38] Family Inclusion of families in activities [38,42,47] Family support including material/instrumental support [35,39,46,47,52] Peers and social networks Social connections [31,32,34,38,39,54] Peer support [38,47,52,53] Competition [38,50] Program staff support, respect, encouragement [36,39,45,47,53] Group activities and exercise companions [42,45,46,53] Participation of others from community network [53] Positive/supportive group atmosphere [39,45] Women-only groups [29,30] | Having an impact and being impacted by others Racism [31,33,38,41] Public judgement [42] Stigma around physical activity [47] Family Families not included [54] Gender roles and responsibilities [32,43] Lack of family support [47] Family commitments including caring for children [31,33,39,42,43,45,46,49,50] Prioritising children’s participation [33] Community/family conflict [34,38] Peers and social network Lack of peer support [32,47] Shame and embarrassment [33,35,36,43,47] Peer rivalry [38] Safety concerns for elderly [18] Conflict with program staff [34] Lack of social interaction [50] Non-Indigenous group atmosphere [46] Cultural obligations, including funerals and Sorry Business [18,45,47] |

| Community/Environment | Community context, safety and resources Access to equipment [53] Appealing and varied locations for activity [36] Community relationships Community health behaviour, attitudes and initiatives [36,48] Community connections [36,38] History and pride [38] Connecting with culture Culturally appropriate/culturally safe environment [31,39,49] Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific facility or activity [41] Cultural activities [35,40,51] | Community context, safety and resources Weather and climate [18,32] Unsafe or inadequate infrastructure [31,32,36,46] General safety concerns [36,42,46] Dangerous dogs [36] Lack of available services/physical activity opportunities [31,33,42] Lack of access to facilities [47] Unappealing outstations [18] Traffic [39] Urban setting [42] Community relationships Unfriendly and uncomfortable neighbourhood [46] Community expectations [38] High community death rates [34] Distractions of community life [18] Connecting with culture Culturally inappropriate activities/lack of cultural inclusiveness [33,51] Disrupted connection with culture and land [41] |

| Program/Policy | Program delivery Provision of transport [45,53] Structured program [53] Free program [39,45,47] Positive program experience [39] Convenient times and location [39] Provision of childcare [39] Program meets needs and expectations [39] Professionalism/well-organised program [39] Program connected to local Aboriginal community-controlled health organisation [45] Flexibility [45] Variety of exercises in program [53] External support Supportive employers [34] Support from services [35] | Program delivery No one to run program [54] Session times and frequency [47,54] Loss of program funding [54] Inconvenient program location [39] Program different to expectations, mismatched with fitness level [39] Lack of sustainable, local physical activity programs [42,43] Insufficient number of programs and locations [44] Lack of motivation, confidence or initiative around chronic disease self-management [44] Lack of knowledge about programs [44] Reliance on welfare [43] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allen, B.; Canuto, K.; Evans, J.R.; Lewis, E.; Gwynn, J.; Radford, K.; Delbaere, K.; Richards, J.; Lovell, N.; Dickson, M.; et al. Facilitators and Barriers to Physical Activity and Sport Participation Experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Adults: A Mixed Method Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189893

Allen B, Canuto K, Evans JR, Lewis E, Gwynn J, Radford K, Delbaere K, Richards J, Lovell N, Dickson M, et al. Facilitators and Barriers to Physical Activity and Sport Participation Experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Adults: A Mixed Method Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189893

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllen, Bridget, Karla Canuto, John Robert Evans, Ebony Lewis, Josephine Gwynn, Kylie Radford, Kim Delbaere, Justin Richards, Nigel Lovell, Michelle Dickson, and et al. 2021. "Facilitators and Barriers to Physical Activity and Sport Participation Experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Adults: A Mixed Method Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189893

APA StyleAllen, B., Canuto, K., Evans, J. R., Lewis, E., Gwynn, J., Radford, K., Delbaere, K., Richards, J., Lovell, N., Dickson, M., & Macniven, R. (2021). Facilitators and Barriers to Physical Activity and Sport Participation Experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Adults: A Mixed Method Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189893