A Study of Environmentally Friendly Menstrual Absorbents in the Context of Social Change for Adolescent Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

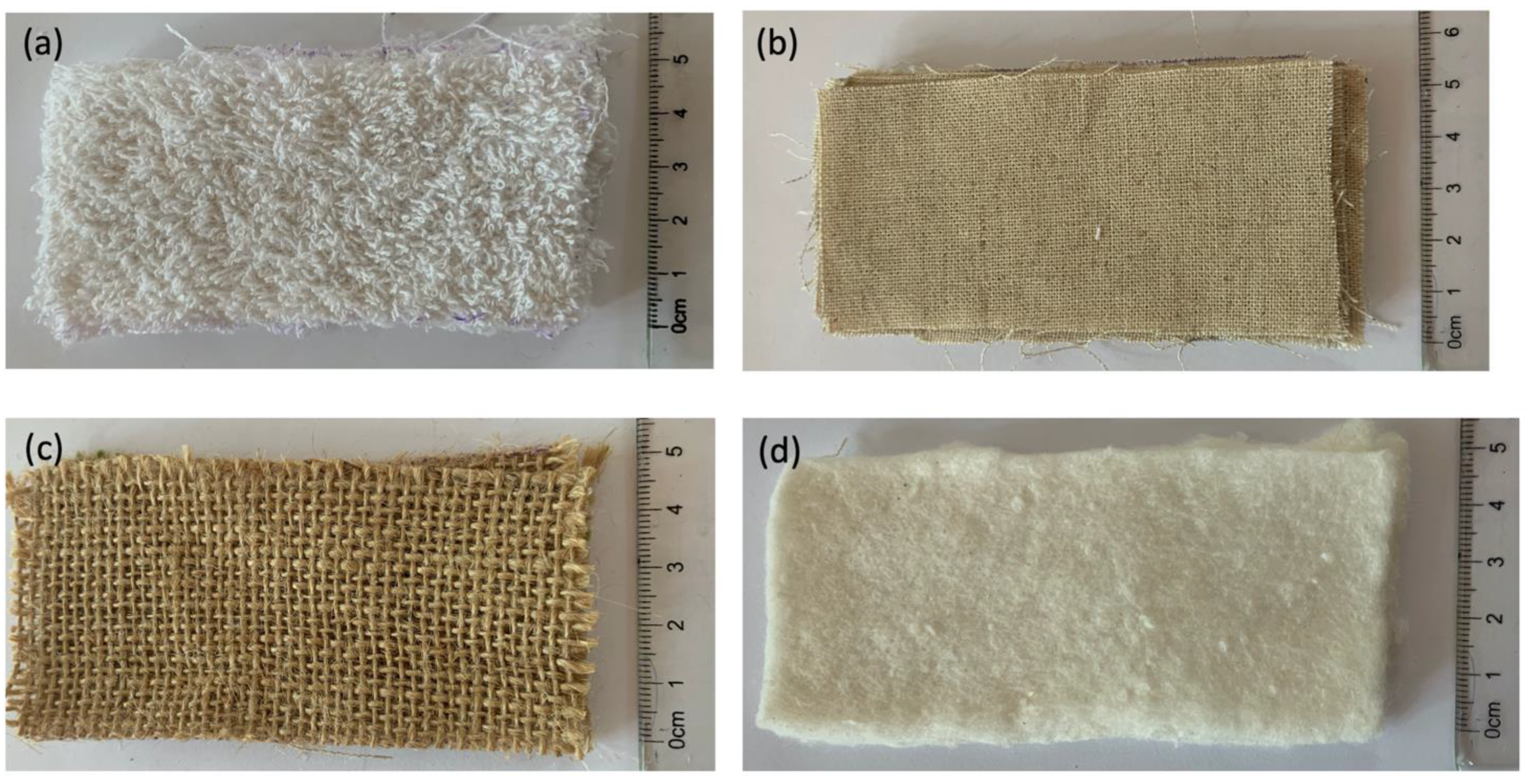

Biodegradable Materials for Sanitary Pads

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sebert Kuhlman, A.; Henry, K.; Lewis Wall, L. Menstrual Hygiene Management in Resource Poor Countries. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2017, 72, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hennegan, J.; Shannon, A.K.; Rubli, J.; Schwab, K.J.; Melendez-Torres, G.J. Women’s and girls’ experiences of menstruation in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e10022803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hennegan, J.; Montgomery, P. Do menstrual hygiene management interventions improve education and psychosocial outcomes for women and girls in low and middle income countries? A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ananda, E.; Singhb, J.; Unisaa, S. Menstrual hygiene practices and its association with reproductive tract infections and abnormal vaginal discharge among women in India. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2015, 6, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, A.M.; Sivakami, M.; Thakkar, M.B.; Bauman, A.; Laserson, K.F.; Coates, S.; Phillips-Howard, P.A. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vashisht, A.; Pathak, R.; Agarwalla, R.; Patavegar, B.N.; Panda, M. School absenteeism during menstruation amongst adolescent girls in Delhi, India. J. Fam. Community Med. 2018, 25, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boosey, R.; Wilson-Smith, E. A vicious cycle of silence: What are the implications of the menstruation taboo for the fulfilment of women and girls’ human rights and, to what extent is the menstruation taboo addressed by international human rights law and human rights bodies? In Research Report. ScHARR Report Series; School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2014; Volume 29, Available online: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/80597/1/A%20vicious%20cycle%20of%20silence%20white%20rose%20report.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Montgomery, P.; Ryus, C.R.; Dolan, C.; Dopson, S.; Scott, L.M. Sanitary Pad Interventions for Girls’ Education in Ghana: A Pilot Study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2004—Girls, Education and Development; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/sowc04/files/SOWC_O4_eng.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Dolan, C.; Ryus, S.; Caitlin, R.; Dopson, S.; Montgomery, P.; Scott, L. A Blind Spot in Girls’ Education: Menarche and its Webs of Exclusion in Ghana. J. Int. Dev. 2014, 26, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hennegan, J.; Dolan, C.; Steinfield, L.; Montgomery, P. A qualitative understanding of the effects of reusable sanitary pads and puberty education: Implications for future research and practice. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elledge, M.F.; Muralidharan, A.; Parker, A.; Ravndal, K.T.; Siddiqui, M.; Toolaram, A.P.; Woodward, K.P. Menstrual Hygiene Management and Waste Disposal in Low and Middle Income Countries-A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pokhrel, D.; Bhattarai, S.; Emgård, M.; Von Schickfus, M.; Forsberg, B.C.; Biermann, O. Acceptability and feasibility of using vaginal menstrual cups among schoolgirls in rural Nepal: A qualitative pilot study. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kaur, K.; Kaur, R. Menstrual Hygiene, Management, and Waste Disposal: Practices and Challenges Faced by Girls/Women of Developing Countries. J. Environ. Public Health 2018, 2018, 1730964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Caruso, B.A.; Torondel, B.; Warren, E.C.; Yamakoshi, B.; Haver, J.; Long, J.; Mahon, T.; Nalinponguit, E.; Okwaro, N.; et al. Menstrual hygiene management in schools: Midway progress update on the “MHM in Ten” 2014–2024 global agenda. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2021, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plesons, M.; Patkar, A.; Babb, J.; Balapitiya, A.; Carson, F.; Caruso, B.A.; Franco, M.; Hansen, M.M.; Haver, J.; Jahangir, A.; et al. The state of adolescent menstrual health in low- and middle-income countries and suggestions for future action and research. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, O.L.; Gowda, R.V. Development and characterization of bamboo and organic cotton fibre blended baby diapers. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 2010. Available online: http://nopr.niscair.res.in/bitstream/123456789/10217/1/IJFTR%2035%283%29%20201-205.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Hosseini Ravandi, S.A.; Valizadeh, M. Properties of fibers and fabrics that contribute to human comfort. In Improving Comfort in Clothing; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2011; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.R. Characterization of biobleaching of Cotton/Linen Fabrics. J. Text. Appar. Technol. Manag. 2008, 6. Available online: https://ojs.cnr.ncsu.edu/index.php/JTATM/article/view/311/251 (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Cruza, J.; Leitão, A.; Silveira, D.; Pichandi, S.; Pinto, M.; Fangueiro, R. Study of moisture absorption characteristics of cotton terry towel fabrics. Procedia Eng. 2017, 200, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, L.; Negulescu, I.; Wu, Q.; Henderson, G. Comparative Study of Hemp Fiber for Nonwoven Composites. J. Ind. Hemp 2007, 12, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Yang, Y.; An, I. Study on Antibacterial Mechanism of Hemp Fiber. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 887, 610–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, M. Application of Natural Fibres in Terry Towel Manufacturing. Int. J. Text. Eng. Process. 2015, 1, 87–91. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275571988_Application_of_Natural_Fibres_in_TerryTowel_Manufacturing (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Ahmad, I.; Farooq, A.; Baig, S.A.; Rashid, M.F. Quality parameters analysis of ring spun yarns made from different blends of bamboo and cotton fibres. J. Qual. Technol. Manag. 2012, 8, 1–12. Available online: http://nopr.niscair.res.in/bitstream/123456789/11215/1/IJFTR%2036(1)%2018-23.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Shanmugasundaram, O.; Gowda, R. Study of Bamboo and Cotton Blended Baby Diapers. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2011, 15, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekerden, F. Effect of pile yarn type on absorbency, stiffness, and abrasion resistance of bamboo/cotton and cotton terry towels. Wood Fiber Sci. 2012, 2, 189–195. Available online: https://wfs.swst.org/index.php/wfs/article/viewFile/335/335 (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Mishra, R.; Behera, B.K.; Pada Pal, B. Novelty of bamboo fabric. J. Text. Inst. 2012, 103, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, N.M.; Ahmad, M.R.; Yahya, M.F.; Fikry, A.; Che Muhamed, A.M.; Razali, R.A. Some Studies on the Moisture Management Properties of Cotton and Bamboo Yarn Knitted Fabrics. Adv. Mater. Res. 2015, 1134, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; Katkar, P.M.; Asagekar, S.D. Natural and Sustainable Raw Materials for Sanitary Napkin. Man-Made Text. India 2018, 46, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheba, A.; Mayeki, S. Bamboo for Green Development? The Opportunities and Challenges of Commercialising Bamboo in South Africa. Human Sciences Research Council. 2017. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/35190753/Bamboo_for_green_developmentThe_opportunities_and_challenges_of_commercialising_bamboo_in_South_Africa (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Musau, Z. Bamboo: Africa’s Untapped Potential. Afr. Renew. 2016, 30, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, L.; Mishra, S.P. Prospect of bamboo as a renewable textile fiber, historical overview, labeling, controversies and regulation. Fash. Text. 2016, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chanana, B. Development of low cost Sanitary Napkins: Breaking MHM taboos of women in India. Int. J. Appl. Home Sci. 2016, 3, 362–371. Available online: http://scientificresearchjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Home-Science-Vol-3_A-362-371-Full-Paper.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Longkumar, A. No Takers for Bamboo Pulp Sanitary Napkin Unit. Morung Express. 2011. Available online: https://morungexpress.com/no-takers-bamboo-pulp-sanitary-napkin-unit (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Sanjeev, G. GOONJ—success through innovation. Emerald Emerg. Mark. Case Stud. 2011, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Dry Weight (g) | Wet Weight (g) | Mass of Absorbed Solution (g) | Absorption Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kotex sanitary pad | 4.45 ± 0.06 | 23.94 ± 0.27 | 19.49 ± 0.21 | 4.38 ± 0.02 |

| Cotton terry cloth | 7.93 ± 0.03 | 14.61 ± 1.23 | 6.67 ± 1.23 | 0.84 ± 0.15 |

| Hemp cloth | 5.75 ± 0.10 | 13.61 ± 0.96 | 7.86 ± 0.97 | 1.40 ±0.17 |

| Linen | 6.55 ± 0.43 | 16.81 ± 0.10 | 10.26 ± 0.44 | 1.57 ± 0.16 |

| Bamboo wadding | 2.50 ± 0.34 | 22.23 ± 0.30 | 19.69 ± 0.06 | 7.86 ± 1.01 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Foster, J.; Montgomery, P. A Study of Environmentally Friendly Menstrual Absorbents in the Context of Social Change for Adolescent Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189766

Foster J, Montgomery P. A Study of Environmentally Friendly Menstrual Absorbents in the Context of Social Change for Adolescent Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189766

Chicago/Turabian StyleFoster, Jasmin, and Paul Montgomery. 2021. "A Study of Environmentally Friendly Menstrual Absorbents in the Context of Social Change for Adolescent Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189766

APA StyleFoster, J., & Montgomery, P. (2021). A Study of Environmentally Friendly Menstrual Absorbents in the Context of Social Change for Adolescent Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9766. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189766