1. Introduction

The enactment of the revised Mental Health Welfare Act has highlighted the importance of mental health promotion services for psychiatric patients in South Korea. In addition, this act has contributed to increased awareness of mental illness and recognition of the importance to prevent, treat, and manage mental illness in addition to hospitals [

1]. In particular, the role of community mental health professionals, who are mental health welfare center practitioners providing mental health promotion services within the community, has been emphasized [

1,

2]. Community mental health professionals include mental health nurses, social professionals and psychologists educated for more than 1 year at a training institution designated by the Ministry of Health and Welfare [

2].

According to a 2018 survey that examined the working conditions of mental health professionals at the Seoul Mental Health Welfare Center, the average length of employment was 3 years, which is shorter than the 6.5-year average length of employment for all South Korean workers in 2018 [

3,

4]. The short duration of employment and the elevated number of turnover factors for community mental health professionals, responsible for the public’s mental health were found to be associated with burnout [

5]. Burnout is defined as physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion that occurs following repeated and long-term exposure to stress in the workplace [

6]. Such burnout is commonly reported by professionals working in mental health facilities [

5].

Burnout is primarily caused by occupational stress related to the work environment [

5,

6], which occurs when the environment is not suitable [

6]. Occupational stress is caused by work-related changes in an individual’s physical, physiological, and psychological conditions due to the environment and conditions they experience in the course of performing their roles. Burnout caused by occupational stress is commonly found in people whose job is to help others, such as community mental health professionals. People whose job involves helping others are placed in an environment where they must provide professional and moral care simultaneously with human empathy. Therefore, people with such jobs continue to experience occupational stress and eventually develop burnout [

7]. Community mental health professionals may experience burnout due to overlapping workplace roles, peer conflict, excessive workload, and employment insecurity [

5]. They often provide services under poor working conditions and insufficient staffing [

2,

5]. This environment increases the likelihood of mental health professionals becoming unable to provide high-quality services [

5].

Burnout may also occur in one’s interpersonal environment, including psychological pressure from interpersonal relationships and secondary trauma stress from vicarious experiences [

8]. A survey of employees at the Korea Mental Health Welfare Center reported that 63.6% of respondents experienced verbal threats from clients, 34.5% experienced threats from client guardians, 33.2% experienced physical assault from clients, and 27.3% experienced emotional sequelae following a client’s suicide [

2]. Among the job responsibilities of community mental health professionals are the identification and registration of clients, home visits for individual case management, and emergency services, which expose them to violent behavior, delusions, and other acts of aggression in interpersonal relationships [

2]. After experiencing symptoms following aggressive behavior from a client in the workplace, mental health professionals may avoid situations reminiscent of the attack and show symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including nightmares and insomnia. In severe cases, negative sequelae include burnout, depression, or suicide [

9].

Not all professionals display symptoms (e.g., PTSD) after experiencing such an attack [

10]. The symptoms of the attack experience are determined by variables corresponding to their personal environment following the experience [

10]. As service providers, such as community mental health professionals, sympathize with clients’ trauma, they experience cognitive changes and the fatigue process—the process of becoming victims themselves [

10]. Thus, it is critical for mental health professionals to recognize and control negative emotions they experience after facing aggressive behavior in the workplace, which requires cognitive emotional regulation strategies and the cognitive control of information that emerges during the experience of a stressful event [

11]. Cognitive emotional regulation strategies can also be a way for individuals to choose how to control their emotions and solve problems in certain situations that stimulate emotional response [

11].

With the increasing importance of balancing the positive and negative outcomes of individuals’ choices in the working process, the concepts of compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction emerged [

8,

12]. Both compassion fatigue and satisfaction contribute to understanding and confirming employee burnout by proving an integrated perspective, and research has confirmed their relevance to burnout [

8]. The compassion satisfaction–compassion fatigue (CS-CF) model is a subjective assessment of the possible factors experienced by professional care providers whose job responsibilities involve working to assist others [

12]. In this model, the variables theorized to precede burnout, compassion satisfaction, and compassion fatigue are divided into work, client, and personal environments [

12]. Compassion fatigue refers to the negative phenomenon experienced by professional care providers while taking care of people who have experienced stressful events [

12]. Increased compassion fatigue has a negative impact on physical and mental health [

8,

12]. This can lead to increased burnout, which can again result in poor quality patient care [

8,

12]. By contrast, professional care providers sometimes feel positive emotions when helping others, which are called compassion satisfaction, and this leads to positive rewards that reduce burnout [

12].

Research has been conducted on compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and burnout among nurses and doctors who may experience aggressive behavior during work [

8]; however, thus far, no research on this topic among community mental health professionals exists, to the best of our knowledge. Previous studies on community mental health professionals included those on the relationship between ordinary job-related variables and the factors influencing them [

5], qualitative research on burnout [

5], or those limited to trauma-related variables without specific mediating variables [

10].

The current study attempted to develop a path model that could explain the pathways to burnout among community mental health professionals, based on the CS-CF model, which might provide insight into reducing burnout by identifying predictor variables, including occupational stress (work environment), experiences with aggressive behavior in the workplace (client environment), and cognitive emotional regulation strategies as input (personal environment). Ultimately, this study attempts to develop a theoretical foundation for human resource management that promotes harmony between service providers and clients and ensures high-quality service by supporting the psychological well-being of community mental health professionals.

Based on existing research, this study tests the CS-CF model to identify the pathways leading to burnout in a sample of community mental health professionals, which might verify the model’s suitability and identify factors contributing to burnout directly and indirectly.

1.1. Study Purpose

Based on Stamm’s CS-CF model [

12], this study aimed to explain mental health professionals’ burnout as being a result of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue, considering the associations of the work, client, and personal environment.

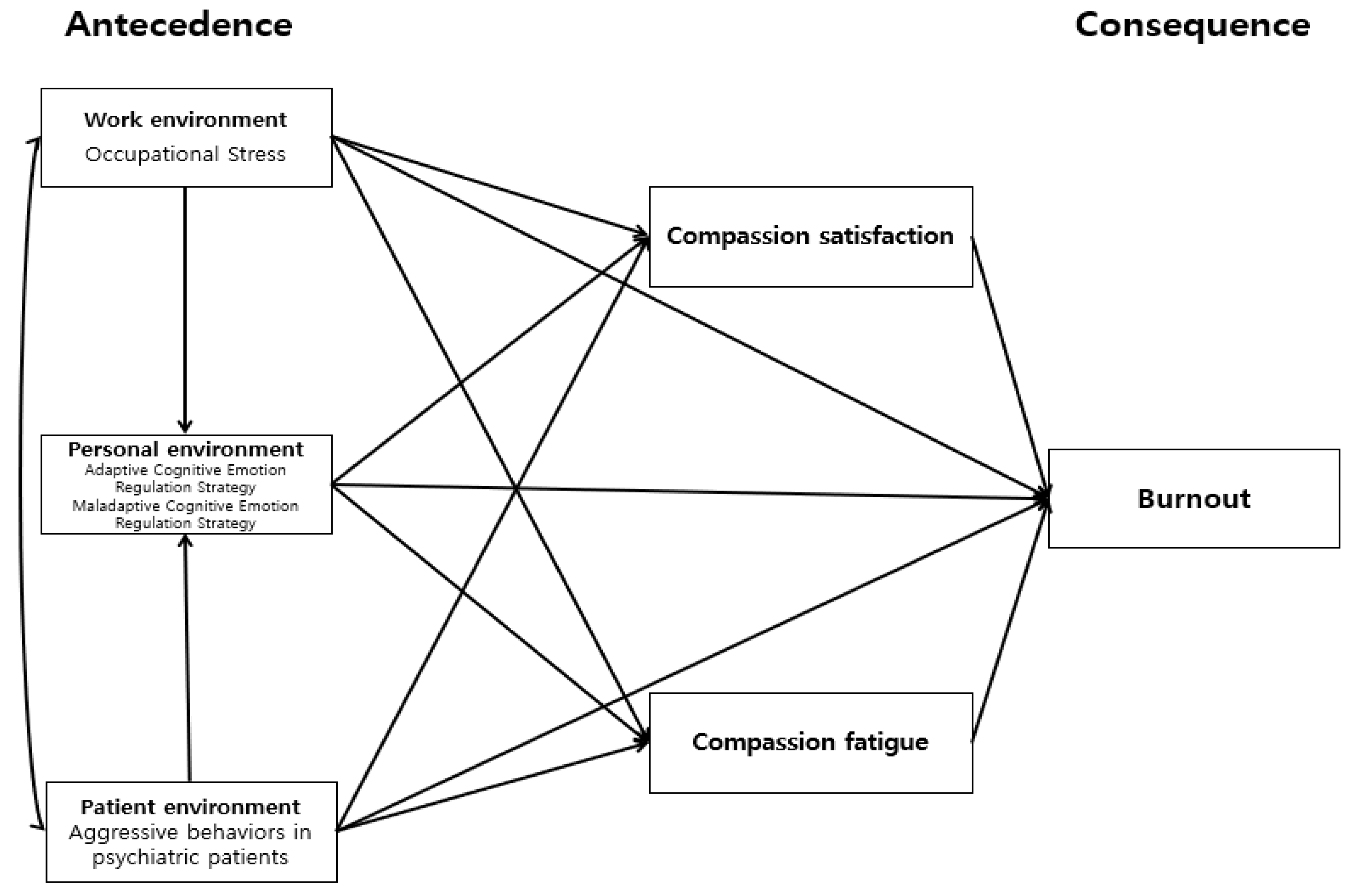

1.2. Conceptual Framework

The CS-CF model, including predictor and outcome variables, and the resulting variables that contribute to compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue, represents a subjective framework for understanding burnout among professional care providers [

12]. In this model, the variables proposed to determine burnout, compassion satisfaction, and compassion fatigue were divided into work, client, and personal environments [

12]. In the CS-CF model’s conceptual framework, the contributing factors are associated with the process, which, in turn, associates the results, and the impact connects in one direction. Stamm et al. [

12] proposed that the three environments would have a negative effect on compassion fatigue and burnout, and a positive effect on compassion satisfaction. The authors further identified the working environment as an environment for work-related care providers. This study defines the working environment as an occupational stressor that occurs when one’s working environment is unsuitable for an individual’s motivation or ability, or when an individual’s ability is ill-suited for the working environment [

6]. Client environment is an environment for caring for clients arising from interactions between care providers and clients [

12]. In this study, the client environment was conceptualized as the clients’ verbal, nonverbal, and physical behaviors threatening community mental health professionals, other people, or property during the provision of service [

12,

13]. The personal environment is that of the care providers [

12], and in this study, it was operationalized as the cognitive emotional regulation strategies following stressful events experienced by community mental health professionals [

11]. The personal environment could be associated with related variables even when individuals are exposed to the same working and client environments [

10]; thus, the working and client environments are associated with the personal environment in this study. The study was designed to complement the CS-CF model to understand the variables leading to burnout (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

This study attempted to identify a path model to explain burnout in community mental health professionals based on the CS-CF model and recognized variables that might reduce it. Burnout was found to significantly differ across age groups and was high in those aged between 26 and 30 years; however, Scheffé’s post-hoc test showed no significant differences between the groups. Jo and Kim [

8] reported that age was inversely correlated with the level of burnout, suggesting that older adults were less likely to experience professional burnout due to unfamiliarity with their work because they had more experience than younger workers. In this study, as for the ratios of community mental health professionals, regarding their age, 8.0% were younger than 25, 40.0% were aged between 26 and 30 years, and 52.0% were 31 or older; thus, the high degree of burnout in those aged 26 to 30 was consistent with Jo and Kim’s findings [

8].

Similarly, Lee and Kim [

19] analyzed burnout among psychiatric nurses using the instruments included in this study and reported that burnout was higher in those younger than 30 compared to those over 50, which was consistent with our results. Since community mental health professionals aged between 26 and 30 years were primarily responsible for practical tasks, such as weekly program management and visiting services for case management, working environment factors were likely to associate their burnout [

3].

The mean burnout among the participants in this study was 27.2. Stamm et al. [

12] examined burnout in a sample representing a variety of professions that included nurses in the United States and reported a mean score of 25, which is lower than that reported in this study. Furthermore, the mean burnout score in this study was also higher than that reported by Lee and Kim [

19], who measured burnout using the Korean version of the ProQOLS developed by Stamm et al. [

12], in a sample of full-time nurses who worked for over a year in psychiatric wards at university hospitals, psychiatric specialty hospitals, and psychiatric clinics. This is likely to be higher in all three, that is, nurses, social professionals, and clinical counselors, who were mental health professionals, rather than those who only worked in hospitals, given the unique nature of the work. Therefore, future research that compares burnout across various regions, occupations, and types of job responsibilities is necessary to gain a broader understanding of burnout and to separate and analyze variables related to its severity, such as environmental and personal characteristics.

In this study, burnout was significantly and positively correlated with occupational stress, experience with aggressive behavior in the workplace, maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, and compassion fatigue, and negatively correlated with adaptive cognitive emotion regulation and compassion satisfaction. Jang and Kim [

20] further examined compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and coping methods in a sample of emergency room nurses and reported that compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue were associated with participants’ coping methods, consistent with this study. The current findings are also consistent with those of Kim and Yeom [

21], who showed that compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction in nurses were the primary burnout predictors. The current results are consistent with those from studies that included samples of nurses, elementary school teachers, play therapists, and emergency medical professionals [

12,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Taken together, occupational stress, experience with aggressive behavior, maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, compassion fatigue, adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, and compassion satisfaction are burnout-related factors.

Considering the variables that could be associated with burnout in community mental health professionals, compassion fatigue was observed to have the greatest positive effect, and compassion satisfaction the largest negative effect. In other words, the greater the compassion fatigue and the lower the compassion satisfaction, the higher the burnout experienced by participants. In addition, Park and Chun [

8] reported that compassion satisfaction in child and youth welfare professionals had a negative effect on burnout, whereas compassion fatigue had a positive effect. They [

8] also described subcategories of compassion fatigue, such as PTSD and vicarious trauma. Specifically, aspects of PTSD that encompass emotional aspects such as negative emotions, constraints, threats, and irritations received from clients, and experiencing clients’ vicarious trauma, appeared to contribute to negative emotions in the relationship with clients [

10]. Thus, it is critical to check variables that can promote compassion satisfaction, a positive factor, and decrease compassion fatigue, a negative factor.

This study demonstrated that occupational stress, which is considered an aspect of the working environment, had no direct effect on burnout, compassion satisfaction, or compassion fatigue; however, it had an indirect effect on both compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue through maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies. In turn, maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, compassion satisfaction, and compassion fatigue were shown to have indirect effects on burnout. Previous research has demonstrated that community mental health professionals experience occupational stress, and ultimately burnout, due to workplace conflicts arising from overlapping roles within multidisciplinary teams across different occupations, identity confusion, lack of systematic education, and job insecurity [

5]. In a qualitative study of mental health social professionals, Jung [

23] reported that participants working at mental health sites were found to have residual occupational stress in their daily lives, which helped them avoid interpersonal relationships. As Jung’s research [

23] was qualitative, direct comparison with this study, which is a quantitative one, might be problematic. However, this study only validated the indirect effects of occupational stress on burnout, rather than the direct effects. The results showed that occupational stress was associated with compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and ultimately burnout through maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation, suggesting that maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation was a mediating variable.

In this study, experience with aggressive behavior, the variable assessing the client environment, was only directly associated with compassion fatigue, and was not directly related to compassion satisfaction or burnout. However, it had indirect effects on compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue through maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Furthermore, maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, compassion satisfaction, and compassion fatigue had indirect effects on burnout. Jung’s study of mental health social professionals [

23] reported that participants faced threatening situations, including verbal aggression, physical aggression, sexual violence, and intimidation, while providing services at mental health sites. In addition, secondary traumatic stress experienced due to clients, compassion satisfaction, and compassion fatigue were identified in a wide range of interpersonal service professionals, such as doctors, mental health professionals, health care professionals, childcare professionals, and social professionals [

23], consistent with this study. Numerous studies have examined the personal and internal responses of professionals after traumatic experiences [

22]. The mediating association of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, even following traumatic experiences, such as mental health professionals’ experiences with aggressive behavior in the workplace, suggests the possibility of having a healthy and positive well-being without showing adverse consequences, such as PTSD.

Adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies, which were measured constructs related to the personal environment of community mental health professionals, did not have direct or indirect effects on burnout, and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies were not directly associated with burnout but indirectly via compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. Maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies had indirect effects on burnout through occupational stress, representing the participants’ working environment, and their experience with aggressive behavior in the workplace, an aspect of the client environment. Increased occupational stress and more numerous experiences with aggressive behavior in the workplace contributed to the use of more maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Such strategies contributed to lowered compassion satisfaction and increased compassion fatigue, ultimately leading to higher burnout. These pathways are consistent with previous research showing that internal, individual protective factors mediate burnout, rather than external factors such as the working environment [

22,

23]. Im [

22] suggested that cognitive emotion regulation strategies in workers were a critical factor that could influence burnout through self-compassion. The results presented by Im [

22] are consistent with those in our study, indicating that cognitive emotion regulation strategies that balance emotions and cognition are critical to the overall delivery of client services, as well as burnout among community mental health professionals.

Maladaptive emotion regulation strategies that had indirect effects on burnout consisted of self-criticism about one’s experiences, blaming others for one’s experiences, rumination (i.e., thinking about feelings and accidents associated with static events), and destructive thinking, emphasizing the terrifying aspects of the experience. A study on the relationships between nurses’ experiences of traumatic events, cognitive emotion regulation strategies, and post-traumatic growth demonstrated that adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies had significant effects on post-traumatic growth [

24]. The current findings also indicate that maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies are a notable mediating variable in the theoretical burnout model for community mental health professionals, which is consistent with the mediating associations of trauma following experiences with aggressive behavior experienced during client service. A study of emergency room nurses by Jang and Kim [

20] showed that their active responses, such as active behavioral coping and positive reinterpretation, negatively affected their compassion fatigue, whereas passive responses such as emotional expression and passive withdrawal affected it positively. Although this study did not assess mental health professionals’ responses, the present findings could be interpreted similarly as cognitive emotion regulation strategies were ways of coping with situations using either adaptive or maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation. Numerous studies have examined the mediating association of hospital conditions with nurses [

20,

21]; however, little research has examined how the working environment of community mental health professionals mediates burnout. Thus, additional research, similar to this study, is needed with samples of community mental health professionals to understand the indirect effects on burnout via compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction, taking into account the aspects of the working, client, and personal environments in multidimensional ways.

This study suggests that cognitive emotion regulation strategies, seen as an aspect of community mental health professionals’ personal environment, represent a variable mediating burnout. Therefore, it is necessary to identify medium-and long-term policies that might ameliorate and manage burnout in community mental health professionals by actively utilizing psychological and emotional development programs, such as cognitive therapy, to reduce maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation. Specifically, programs should be developed that can help individuals who rely on inefficient regulation strategies, such as self-criticism, blaming others, constant thinking about feelings and accidents related to negative events, and emphasizing the fear of experience, to cope with conflict.

This study had several limitations. First, it did not consider various factors that could affect burnout among community mental health professionals. Second, it analyzed a path model for burnout that did not separate participants by specific occupation (e.g., mental health nurses, mental health social welfare professionals, and mental health clinical counselors). Third, in-depth analysis by occupation, and considering the characteristics of each job, will be required in the future. Finally, the study method requires discretion when attempting to generalize the results of this study. In addition, this study used a convenience sampling method to select mental health professionals working at mental health promotion centers throughout South Korea as participants; thus, further studies that include more widespread research sites and diverse participant groups are needed. This study also built on the cross-sectional data. The evidence to support this model based on the current cross-sectional data may be insufficient to draw causality, and more studies, including longitudinal and intervention studies, are needed to confirm the model.