Assessing Concerns and Care Needs of Expectant Parents: Development and Feasibility of a Structured Interview

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Instrument

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Analysis

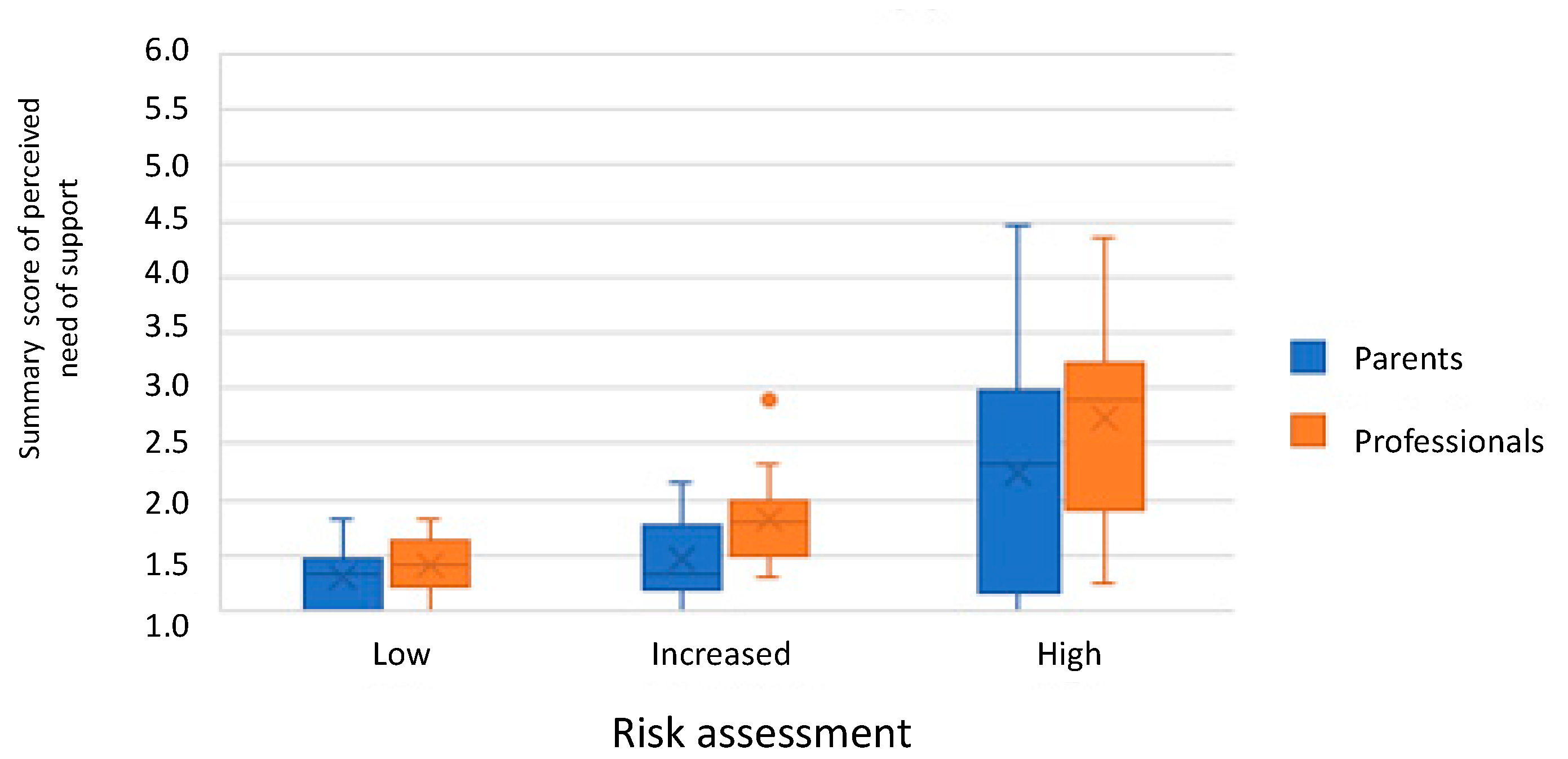

3. Results

User Experience

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glascoe, F.P. Early Detection of Developmental and Behavioral Problems. Pediatr. Rev. 2000, 21, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Expert Groep. Zorgstandaard Integrale Geboortezorg; College Perinatale Zorg: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Nkansah-Amankra, S.; Dhawain, A.; Hussey, J.R.; Luchok, K.J. Maternal social support and neighborhood income inequality as predictors of low birth weight and preterm birth outcome disparities: Analysis of South Carolina pregnancy risk assessment and monitoring system survey, 2000–2003. Matern. Child Health J. 2010, 14, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detmar, S.; De Wolff, M.S. De 1e 1000 Dagen: Het Versterken van de Vroege Ontwikkeling—Een Literatuurverkenning ten Behoeve van Gemeenten; TNO: Leiden, the Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Loomans, E.M.; van Dijk, A.E.; Vrijkotte, T.G.M.; van Eijsden, M.; Stronks, K.; Gemke, R.J.B.J.; Van den Bergh, B.R.H. Psychosocial stress during pregnancy is related to adverse birth outcomes: Results from a large multi-ethnic community-based birth cohort. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 23, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijpers, F. Prenataal Huisbezoek Door de Jeugdgezondheidszorg; Nederlands Centrum Jeugdgezondheid: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker, D.; Davis, M.S.; Squires, J.M. Mental Health Screeing in Young Children. Infants Young Child. 2004, 17, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.S.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Davis, O. Assessment of young children’s social emotional development. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Carter, A.S.; Irwin, J.R.; Wachtel, K.; Cicchetti, D.V. The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment: Screening for Social-Emotional Problems and Delays in Competence. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2004, 29, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijneveld, S.A.; Brugman, E.; Verhulst, F.C.; Verloove-Vanhorick, S.P. Identification and management of psychosocial problems among toddlers in Dutch preventive child health care. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Holmes, C.A. Improving the early detection of children with subtle development problems. J. Child Heal. Care 2004, 8, 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Vink, R.; van Sleuwen, B.; Boere-boonekamp, M. Evaluatie Prenatale Huisbezoeken JGZ ZonMw-Project in Het Kader van Programma “Vernieuwing Uitvoeringspraktijk Jeugdgezondheidszorg”; TNO: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns, J.; Öry, F.; Schrijvers, G. Helpen bij Opgroeien en Opvoeden: Eerder, Sneller en Beter. Een advies over Vroegtijdige Signalering en Interventies bij Opvoed- en Opgroeiproblemen; de Inventgroep: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 1–144. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on psychosocial aspects of child and family health and task force on mental health. The Future of Pediatrics: Mental Health Competencies for Pediatric Primary Care. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, A.A.; Van Veen, M.J.; Birnie, E.; Denktas, S.; Steegers, E.A.; Bonsel, G.J. An instrument for broadened risk assessment in antenatal health care including non-medical issues. Int. J. Integr. Care 2016, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steegers, E. Sociale verloskunde voorkomt armoedeval. Med. Contact 2013, 68, 714–717. [Google Scholar]

- Zwijgers, P.; Carmiggelt, B. Ben Ik in Beeld ? Definities Jeugdgezondheidszorg In Beeld, In Zorg en Bereik; Nederlands Centrum Jeugdgezondheid: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Oudhof, M.; de Wolff, M.S.; de Ruiter, M.; Kamphuis, M.; L’Hoir, M.P.; Prinsen, B. JGZ Richtlijn Opvoedingsondersteuning Voor Hulp bij Opvoedingsvragen en Lichte Opvoedproblemen; Nederlands Centrum Jeugdgezondheid: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 1–228. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, P.; Ghate, D.; van der Merwe, A. What Works in Parenting Support ? A Review of the International Evidence; Report No.:E RR574; Department for Education and Skills: Nottingham, UK, 2004; pp. 1–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppenbrouwers, K.; De Cock, P. Onderzoek Naar de Wetenschappelijke State of the Art op Het Vlak van Preventieve Gezondheidszorg Voor Kinderen Onder de 3 Jaar; Kind & Gezin: Leuven, Belgium, 2010; pp. 1–129. [Google Scholar]

- Theunissen, M.; de Wolff, M. JGZ-richtlijn Psychosociale Problemen; Nederlands Centrum Jeugdgezondheid: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid Welzijn en Sport. Basistakenpakket Jeugdgezondheidszorg 0–19 Jaar; Ministerie van Volksgezondheid Welzijn en Sport: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Nederlands Centrum Jeugdgezondheid (NCJ). Landelijk Professioneel Kader—Uitvoering Basispakket Jeugdgezondheidszorg (JGZ); Nederlands Centrum Jeugdgezondheid (NCJ): Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid Welzijn en Sport. Wetswijziging “Prenataal huisbezoek door de JGZ” Is Aangenomen. Available online: https://www.kansrijkestartnl.nl/actueel/nieuws/2021/06/23/wetswijziging-prenataal-huisbezoek-door-de-jgz-is-aangenomen (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Vink, R.M.; Detmar, S. Psychosociale risicosignalering in de zwangerschap, een overzicht van Nederlandse instrumenten. Tijdschr Voor Gezondh. 2012, 90, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staal, I.I.E.; van den Brink, H.A.G.; Hermanns, J.M.A.; Schrijvers, A.J.P.; van Stel, H.F. Assessment of parenting and developmental problems in toddlers: Development and feasibility of a structured interview. Child. Care. Health Dev. 2011, 37, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staal, I.I.E.; Hermanns, J.M.A.; Schrijvers, A.J.P.; van Stel, H.F. Risk assessment of parents’ concerns at 18 months in preventive child health care predicted child abuse and neglect. Child Abus. Negl. 2013, 37, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- van Stel, H.F.; Staal, I.I.; Hermanns, J.M.; Schrijvers, A.J. Validity and reliability of a structured interview for early detection and risk assessment of parenting and developmental problems in young children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staal, I.I.E.; van Stel, H.F.; Hermanns, J.M.A.; Schrijvers, A.J.P. Early detection of parenting and developmental problems in toddlers: A randomized trial of home visits versus well-baby clinic visits in the Netherlands. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staal, I.I.E.; van Stel, H.F.; Hermanns, J.M.A.; Schrijvers, A.J.P. Early detection of parenting and developmental problems in young children: Non-randomized comparison of visits to the well-baby clinic with or without a validated interview. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 62, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nu Niet Zwanger. Een Eerlijk Gesprek over Kinderwens, Seksualiteit en Anticonceptie Zodat Kwetsbare Mensen (m/v) Niet Onbedoeld Zwanger Raken. Available online: https://www.nunietzwanger.nl (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Wulffraat, A.; Blanchette, L.; Bertens, L.; Ernst, H.; van der Meer, L.; de Graaf, H. Definitie Kwetsbaarheid—Zwangere Vrouwen; Gemeente Rotterdam en afdeling Verloskunde & Gynaecologie Erasmus EC: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Caris, C.J. Let’s Talk. A Study on Parenting Support at the Well-Baby Clinic; SWP Uitgeverij: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO). Your Research: Is It Subject to the WMO or Not? Available online: https://english.ccmo.nl/investigators/legal-framework-for-medical-scientific-research/your-research-is-it-subject-to-the-wmo-or-not (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Bellis, M.A.; Hughes, K.; Ford, K.; Ramos Rodriguez, G.; Sethi, D.; Passmore, J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e517–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijlstra, M.; Prinsen, B.; Schulpen, T. Kwetsbaar Jong; Uitgeverij S.W.P.: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sidebotham, P.; Heron, J. ALSPAC Study Team Child maltreatment in the “children of the nineties”: A cohort study of risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. 2005, 30, 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Lynch, M.A. Predicting child abuse: Signs of bonding failure in the maternity hospital. Br. Med. J. 1977, 1, 624–626. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, L.; Anderson, P.; Battin, M.; Bowen, J.; Brown, N.; Callanan, C.; Campbell, C.; Chandler, S.; Cheong, J.; Darlow, B.; et al. Long term follow up of high risk children: Who, why and how? BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Minde, M.R.C.; Blanchette, L.M.G.; Raat, H.; Steegers, E.A.P.; De Kroon, M.L.A. Reducing growth and developmental problems in children: Development of an innovative postnatal risk assessment. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, R.; Yan, T. Sensitive Questions in Surveys. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 859–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Topics | Main Question(s) | Illustrative Examples (such as e.g., ….) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Summary of period before pregnancy | How was your life before you were pregnant? | We first start with reviewing the period before you were pregnant. What was your life like without children? How was your own childhood? |

| 2. Pregnancy experience | How do you like being pregnant? | Mood, reactions from others Is your pregnancy planned, desired? How do the people around you react to the news of your pregnancy? Do you notice any contact with your baby already? |

| 3. Health and lifestyle | How do you think about your own health and lifestyle (now that you are pregnant)? Do you pay attention to that? How do you do that? | Physical growth, healthy diet, exercise, sleep, fever, (chronic or frequent) illnesses, smoking, drinking, drug use How will you integrate these principles after your child has been born/into raising your child? Are there any illnesses that are common in your family? |

| 4. Looking ahead to giving birth | We look forward to the birth | Expectations, feelings, place where to give birth, preparation, pregnancy gym, yoga or course Who would you like near you while giving birth? Has childcare already been arranged for the other children? Have you thought about how you are going to travel to the hospital? And after childbirth? |

| 5. Looking ahead to the first days after birth | What do you expect from the maternity period? | Maternity care, living area, day–evening–night rhythm Have you thought about your preference with regard to your child’s nutrition? What preparation did you undertake? What are your preferences with regard to visits from other people? |

| 6. Looking ahead to raising your child | Do you already have ideas on raising your child? | Crying, regularity, sleeping Are you, as a father and a mother, in agreement on parenting? How was your family upbringing when you were a child? Do you know what to expect from me and my colleagues from the preventive child healthcare services? |

| 7. Language use of (expectant) parents (if relevant) | Which language(s) do you speak at home? Have you thought about what language you are going to speak with your child? | Choice of sthe poken language, bilingual upbringing Do you experience difficulties reading a brochure in Dutch or with filling out forms? What is your experience with talking to healthcare providers? |

| 8. Living environment in and outside the home | Do you have any questions or need information about your living environment and the environment outside your home? | Room and opportunity for the child to play, hygiene and safety at home, housing problems, safety or violence in the neighbourhood, discrimination or cohesion in the neighbourhood Do you like the house and the neighborhood where you live? Is this a kid-friendly neighborhood? |

| 9. Social contacts and informal support | How do you experience the amount and quality of social contacts and informal support? (with respect to your pregnancy and looking ahead to raising your child) | Need for contacts, need for support from others, need someone to share experiences with, need for logistical support Who could you call if you happen to start labor? Do you have any family members that live near you? How is your relationship with them? Does this feel like enough? |

| 10. Concerns communicated by others | Has anybody (for example, your obstetric care provider, employer, parents, parents in law or neighbor) ever indicated any worries? Note: the nurse can also refer to the reason for their visit. | Do you recognize their worries? How did you respond to their worries? |

| 11. Family issues | Sometimes, external factors can influence your expectant child. Such as | Health problems from other family members (are you an informal caregiver?), lifestyle of the (expectant) father, addiction, psychiatric problems, relationship problems, financial problems Are you and the (expectant) father of the child happy together? If unmarried, have you thought about steps to undertake in terms of the legal acknowledgement of your child? Does one of you have a job or do you both work? Have you had any financial consequences from the crisis? |

| 12. Looking at your (own) future | What are your expectations for the future after your child has been born? | Work and/or study, day-care, time for yourself, desire to have more children, role of partner/colleague/friend, sexuality and anticonception * Have you thought about pregnancy/maternity leave? For how long can you take a leave? Will you go back to work afterwards? Have you already thought about how you can fulfill other roles in addition to your mother role? |

| 13. Forgot something? | Do you have any questions or do you need information on a topic that has not been covered during our conversation? | There might be questions about other child(ren) in the family |

| Topics | Parent Concerns | Perceived Need of Support | p-Value * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents Assessment * | Professional Assessment * | |||||

| Concerned/very Concerned (%) | Information Wanted/Personal Advice/Counselling (%) | Intensive Help/Immediate Intervention Required (%) | Information/Personal Advice/Counselling (%) | Intensive Help/Immediate Intervention Required (%) | Parents vs. Professional | |

| Summary of period before pregnancy | 31.9 | 23.9 | 13.0 | 34.9 | 14.0 | 0.34 |

| Pregnancy experience | 10.2 | 19.6 | 6.5 | 34.9 | 7.0 | 0.014 |

| Health and lifestyle | 6.0 | 25.5 | 2.1 | 43.2 | 0 | 0.13 |

| Looking ahead to giving birth | 14.3 | 29.8 | 6.4 | 45.7 | 8.7 | 0.033 |

| Looking ahead to the first days after birth | 14.0 | 43.5 | 6.5 | 57.4 | 6.4 | 0.44 |

| Looking ahead to raising your child | 2.0 | 37.0 | 2.2 | 73.9 | 2.2 | <0.001 |

| Language use | 5.1 | 25.7 | 2.9 | 48.6 | 2.9 | 0.009 |

| Living environment (in and outside the home) | 14.0 | 10.6 | 8.5 | 23.9 | 8.7 | 0.014 |

| Social contacts and informal support | 8.2 | 17.8 | 2.2 | 31.8 | 2.3 | 0.016 |

| Concerns communicated by others | 21.3 | 21.3 | 10.6 | 39.1 | 10.9 | 0.004 |

| Family issues | 30.6 | 27.9 | 9.3 | 44.2 | 9.3 | 0.011 |

| Looking at your (own) future | 8.5 | 7.0 | 4.7 | 16.3 | 7.0 | 0.034 |

| Forget something? | 8.3 | 0 | 23.1 | 0 | 0.100 | |

| Parent Assessment of Perceived Need of Support | Professional Assessment of Perceived Need of Support | Risk Assessment Professional | Parents with Low Education | Parents Unemployed/Unemployable | Not Two-Parent Household | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent concerns | 0.53 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.80 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.37 * | 0.27 |

| Parent assessment of perceived need of support | 0.60 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.07 | |

| Professional assessment of perceived need of support | 0.71** | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.28 | ||

| Risk assessment | 0.51 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.41 ** |

| Low-Risk Group N(%) | Increased-Risk Group N(%) | High-Risk Group N(%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family characteristics | 0.041 | |||

| Two-parent household | 14 (93.3) | 14 (77.8) | 5 (45.5) | |

| One-parent household | 2 (11.1) | 3 (27.3) | ||

| Shared household | 3 (27.3) | |||

| Other (foster family/adoption/divorcement/living with grandparents) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (11.1) | 0 | |

| Parent characteristics | ||||

| Age mother, mean in years (SD) | 28 (SD 6.2) | 25 (SD 2.8) | 29 (SD 6.7) | 0.24 |

| Mother age <20 years at birth | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Age father, mean in years (SD) | 30 (SD 7.5) | 26 (SD 3.0) | 30 (SD 4.4) | 0.15 |

| Father age <20 years at birth | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0.56 |

| Ethnicity: non-Dutch mother | 8 (53.3) | 6 (31.6) | 5 (35.7) | 0.42 |

| Ethnicity: non-Dutch father | 6 (54.5) | 5 (38.5) | 4 (50.0) | 0.73 |

| Language: non-Dutch used at home by the mother | 6 (50.0) | 5 (31.3) | 4 (40.0) | 0.61 |

| Language: non-Dutch used at home by the father | 5 (41.7) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (14.3) | 0.36 |

| Education Mother | 0.048 | |||

| Low | 2 (16.7) | 4 (26.7) | 7 (63.6) | |

| Intermediate | 6 (50.0) | 8 (53.3) | 3 (27.3) | |

| High | 4 (33.3) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Education Father | 0.081 | |||

| Low | 4 (30.8) | 5 (38.5) | 7 (77.8) | |

| Intermediate | 4 (30.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1 (11.1) | |

| High | 5 (38.5) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (11.1) | |

| Employment Mother | 0.71 | |||

| Employed | 6 (40.0) | 2 (11.1) | 0 | |

| Unemployed | 6 (40.0) | 8 (44.4) | 7 (58.3) | |

| Unemployable/unable to work | 0 | 4 (22.2) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Employment Father | 0.36 | |||

| Employed | 10 (66.7) | 14 (82.4) | 3 (27.3) | |

| Unemployed | 2 (13.3) | 2 (11.8) | 5 (45.5) | |

| Unemployable/unable to work | 0 | 0 | 3 (37.3) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Driessche, A.; van Stel, H.F.; Vink, R.M.; Staal, I.I.E. Assessing Concerns and Care Needs of Expectant Parents: Development and Feasibility of a Structured Interview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9585. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189585

van Driessche A, van Stel HF, Vink RM, Staal IIE. Assessing Concerns and Care Needs of Expectant Parents: Development and Feasibility of a Structured Interview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9585. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189585

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Driessche, Anne, Henk F. van Stel, Remy M. Vink, and Ingrid I. E. Staal. 2021. "Assessing Concerns and Care Needs of Expectant Parents: Development and Feasibility of a Structured Interview" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9585. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189585

APA Stylevan Driessche, A., van Stel, H. F., Vink, R. M., & Staal, I. I. E. (2021). Assessing Concerns and Care Needs of Expectant Parents: Development and Feasibility of a Structured Interview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9585. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189585