A Qualitative Study on Nudging and Palliative Care: “An Attractive but Misleading Concept”

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Findings

3.2.1. Translating Nudging in the Palliative Care Setting: Something Attractive but Dangerous

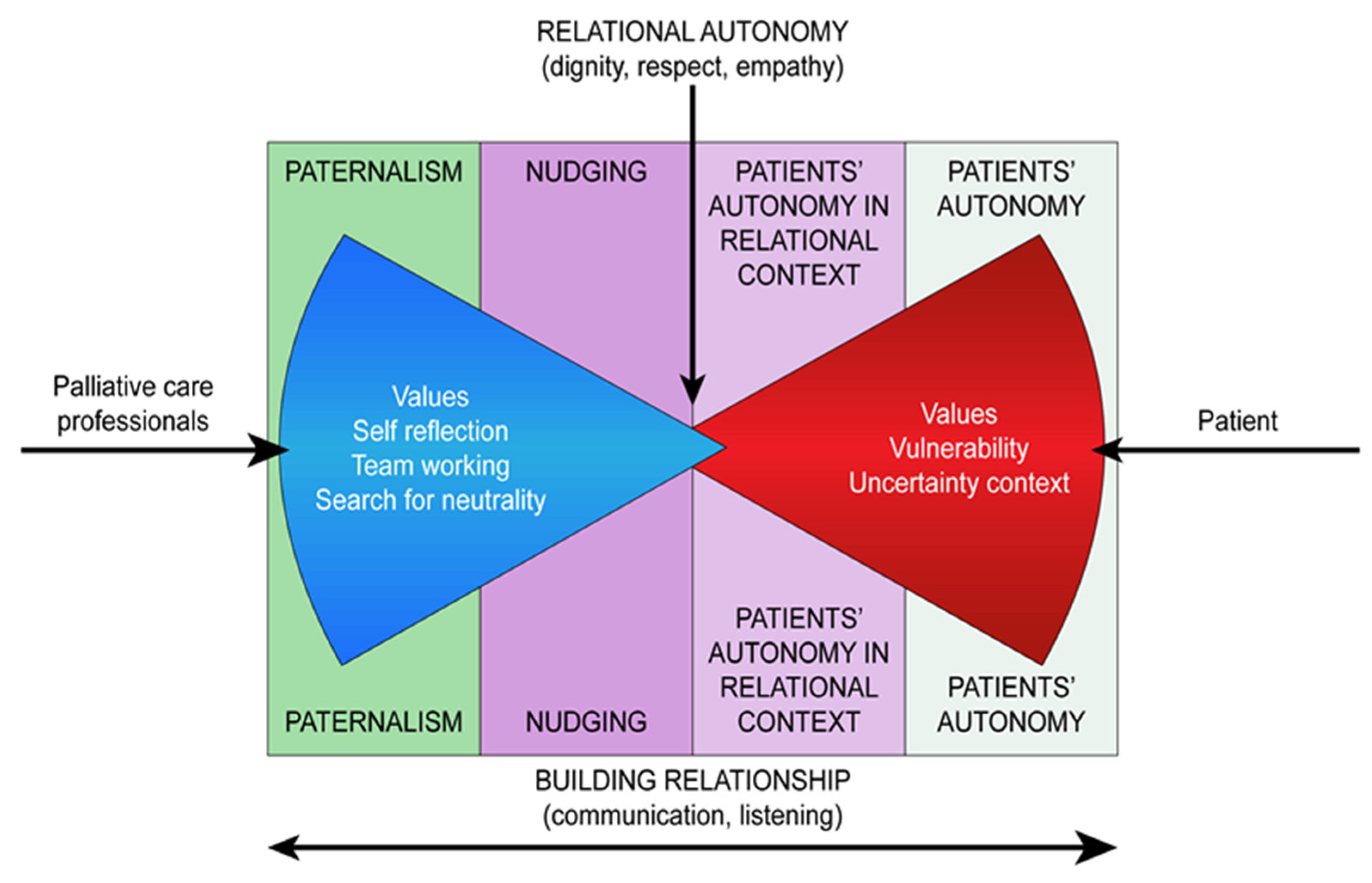

3.2.2. Towards a Neutral Space

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beachaump, T.; Childress, J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 7th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S.D. Three versions of an ethics of care. Nurs. Philos. 2009, 10, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, E.D.; Thomasma, D.C. The Virtues in Medical Practice, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Copp, D. Handbook of Ethical Theory, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cassileth, B.R.; Soloway, M.S.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Schellhammer, P.S.; Seidmon, E.J.; Hait, H.I.; Kennealey, G.T. Patients’ choice of treatment in stage D prostate cancer. Urology 1989, 33, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, S. Debate: State paternalism, neutrality and perfectionism. J. Polit. Philos. 2006, 14, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C.R.; Thaler, R.H. Libertarian paternalism is not an oxymoron. Univ. Chicago Law Rev. 2003, 70, 1159–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, L. Sulle spinte gentili del nudge: Un quadro d’insieme. Più libertà o nuovo paternalismo? Epidemiol. Prev. 2016, 40, 462–465. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal-Barby., J.; Opel, D.J. Nudge or Grudge? Choice Architecture and Parental decision-Making. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2018, 48, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelfand, S.D. The Meta-Nudge - A Response to the Claim That the Use of Nudges During the Informed Consent Process is Unavoidable. Bioethics 2016, 30, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, C.; Proudfoot, E. Nudging and the complicated real life of “informed consent”. Am. J. Bioeth. 2013, 13, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, D.J.; Ladin, K.; Mathew, P. The ethical imperative of healthy paternalism in advance directive discussions at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 429–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeland, E.; Cain, J.; Onderdonk, C.; Kerr, K.; Mitchell, W.; Thornberry, K. When open-ended questions don’t work: The role of palliative paternalism in difficult medical decisions. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C. Goals of Care in a Pandemic: Our Experience and Recommendations. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020, 60, e15–e17. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery, C.; Lewis, E.; Cardona, M. The Crucial Role of Nurses and Social Workers in Initiating End-of-Life Communication to Reduce Overtreatment in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gerontology 2020, 66, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Negro, S.M.L.; Borghi, L.; Ferrari, D.; Vegni, E. Comunicare l’indicibile: Proposte dalla medicina centrata sul paziente al paternalismo palliativo. Recenti Prog. Med. 2017, 108, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marron, J.M.; Truog, R.D. Against “healthy paternalism” at the end of life. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, S. Authenticity, best interest, and clinical nudging. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2017, 47, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Panfilis, L.; Tanzi, S.; Perin, M.; Turola, E.; Artioli, G. “Teach for ethics in palliative care”: A mixed-method evaluation of a medical ethics training programme. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, I. Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare; Wiley: Blackwell, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitzinger, J. The methodology of Focus Groups: The importance of interaction between research participants. Sociol. Health Illn. 1994, 16, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noggle, R. Manipulation, salience, and nudges. Bioethics 2018, 32, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, A. The physician-patient relationship and the ethic of care. CMAJ 1993, 148, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar]

- TenHave, H. Vulnerability: Challenging Bioethics; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, C.; Rogers, W.; Dodds, S. Vulnerability: New Essays in Ethics and Feminist Philosophy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mortari, L. Filosofia Della Cura; Raffaello Cortina: Milano, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmaster, C.B. What does vulnerability mean? Hastings Cent. Rep. 2006, 36, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, V. Justice and Care: Essential Reading in Feminist Ethics; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tronto, J.C. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, R. Feminine and Feminist Ethics; Wadsworth Publishing Company: Belmont, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Donchin, A. Reworking autonomy: Toward a feminist perspective. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 1995, 4, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, B.H. Four approaches to doing ethics. J. Med. Philos. 1996, 21, 7–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricou, C.; Yennu, S.; Ruer, M.; Bruera, E.; Filbet, M. Decisional control preferences of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care. Palliat. Support. Care 2018, 16, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabasenche, W.P. Forming the Self: Nudging and the Ethics of Shaping Autonomy. Am. J. Bioeth. 2016, 16, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhondali, W.; Perez-Cruz, P.; Hui, D.; Chisholm, M.S.; Dalal, S.; Baile, W.; Chittenden, E.; Bruera, E. Patient-physician communication about code status preferences: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2013, 119, 2067–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branch, W.T. A piece of my mind. The ethics of patient care. JAMA 2015, 313, 1421–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | Do you think that clinical nudging occurs in your daily care relationship? |

| 2 | Does palliative care approach differ from clinical nudging? If yes, how? |

| 3 | Are there ways to oppose nudging? |

| Code | Professional Features | Years of Experience in PC | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Specialist in Palliative Medicine | 8 | Female |

| 2 | Specialist in Palliative Medicine | 4 | Female |

| 3 | Nurse in Palliative Medicine | 1 | Female |

| 4 | Nurse in Palliative Medicine | 5 | Female |

| 5 | Psychologist | 15 | Female |

| 6 | Psychologist | 10 | Female |

| 7 | Specialist in Palliative Medicine | 30 | Male |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Panfilis, L.; Peruselli, C.; Artioli, G.; Perin, M.; Bruera, E.; Brazil, K.; Tanzi, S. A Qualitative Study on Nudging and Palliative Care: “An Attractive but Misleading Concept”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189575

De Panfilis L, Peruselli C, Artioli G, Perin M, Bruera E, Brazil K, Tanzi S. A Qualitative Study on Nudging and Palliative Care: “An Attractive but Misleading Concept”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189575

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Panfilis, Ludovica, Carlo Peruselli, Giovanna Artioli, Marta Perin, Eduardo Bruera, Kevin Brazil, and Silvia Tanzi. 2021. "A Qualitative Study on Nudging and Palliative Care: “An Attractive but Misleading Concept”" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189575