Views and Experiences of LGBTQ+ People in Prison Regarding Their Psychosocial Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

- To synthesize the best available qualitative evidence regarding the views and experiences LGBTQ+ people in prisons and their psychosocial needs;

- To identify psychosocial interventions and supports of LGBTQ+ people in prisons;

- To highlight areas of good practice regarding meeting the psychosocial needs of LGBTQ+ people in prisons

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Quality Assessment

3. Results

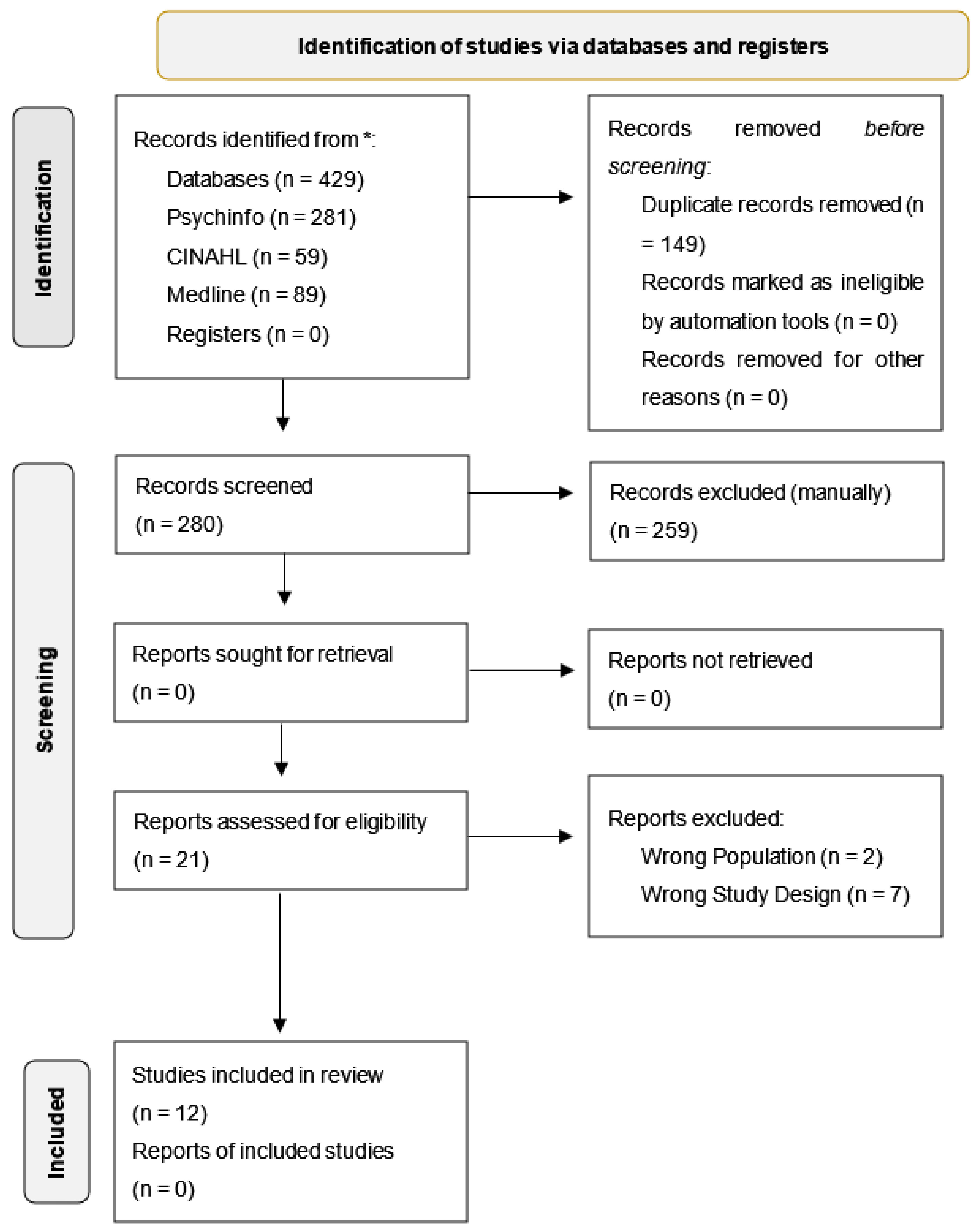

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Study Characteristics

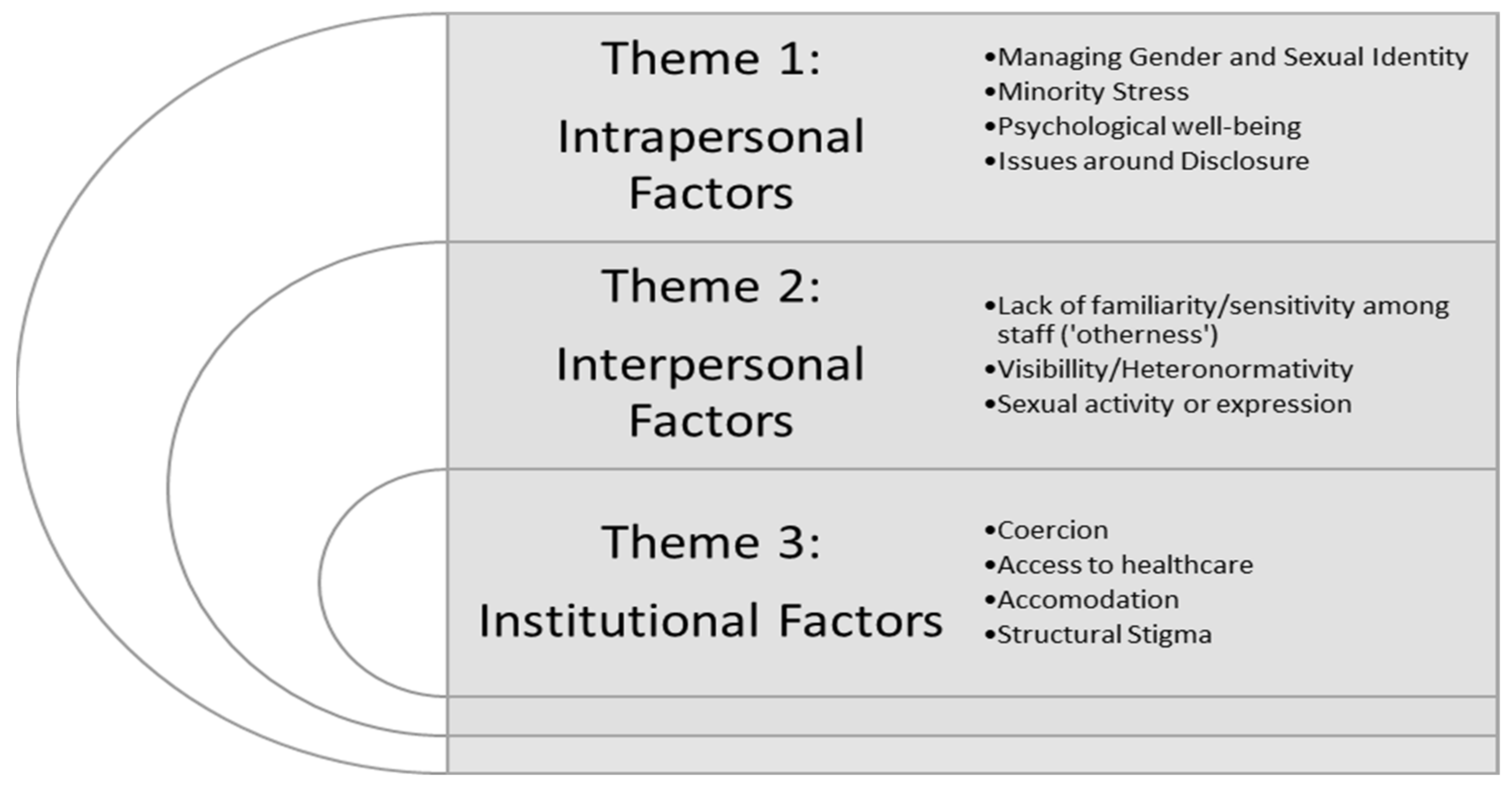

3.3. Thematic Analysis

3.3.1. Theme One: Intrapersonal Factors

3.3.2. Theme Two: Interpersonal Factors

3.3.3. Theme Three: Institutional Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy

4.2. Education and Practice Development

4.3. Practice

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mereish, E.H.; Poteat, V.P. A relational model of sexual minority mental and physical health: The negative effects of shame on relationships, loneliness, and health. J. Couns. Psychol. 2015, 62, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentine, S.E.; Shipherd, J.C. A systematic review of social stress and mental health among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 66, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lydon, J.; Carrington, K.; Low, H.; Miller, H.; Yazdy, M. Coming Out of Concrete Closets: A Report on Black & Pink’s National LGBTQ Prisoner Survey; Black and Pink: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann, B.; Cahill, S.; Wang, P.; Levengood, T. Emerging Best Practices for the Management and Treatment of Incarcerated Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex (LGBTI) Individuals; The Fenway Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Handbook on Prisoners with Special Needs; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Vienna, Austria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Majd, K.; Marksamer, J.; Reyes, C. Hidden injustice: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Juvenile Courts. Legal Services for Children, National Juvenile Defender Center, and National Center for Lesbian Rights. 2009. Available online: http://www.equityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/hidden_injustice.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Rosario, M.; Schrimshaw, E.W.; Hunter, J. Risk factors for homelessness among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A developmental milestone approach. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Snapp, S.D.; Hoenig, J.M.; Fields, A.; Russell, S.T. Messy, Butch, and Queer: LGBTQ Youth and the School-to-Prison Pipeline. J. Adolesc. Res. 2015, 30, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.E.; Herman, J.L.; Rankin, S.; Keisling, M.; Mottet, L.; Anafi, M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey; National Center for Transgender Equality: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 184–190. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, I.H.; Flores, A.R.; Stemple, L.; Romero, A.P.; Wilson, B.D.; Herman, J.L. Incarceration Rates and Traits of Sexual Minorities in the United States: National Inmate Survey, 2011–2012. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.R. Qualitative Analysis of Transgender Inmates’ Correspondence: Implications for Department of Correction. J. Correct. Health Care 2014, 20, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenness, V.; Maxson, C.; Matsuda, K. Violence in California Correctional Facilities: An Empirical Examination of Sexual Assault; California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Routh, D.; Abess, G.; Makin, D.; Stohr, M.; Hemmens, C.; Yoo, J. Transgender Inmates in Prisons: A Review of Applicable Statutes and Policies. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2017, 61, 645–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, E.F.; Khin, E.K. Fundamental Principles Inherent in the Comprehensive Care of Transgender Inmates. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law Online 2014, 42, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003, 42 USC §5101–5106. Available online: https://www.ojjdp.gov/about/PubLNo108-79.txt (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Yogyakarta Principles. The Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. 2006. Available online: http://yogyakartaprinciples.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/A5_yogyakartaWEB-2.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- National Institute of Corrections in the USA. Policy Review and Development Guide: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex Persons in Custodial Settings, 2nd ed. U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Corrections National Institute of Corrections: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://info.nicic.gov/sites/info.nicic.gov.lgbti/files/lgbti-policy-review-guide-2_0.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software, Melbourne, Australia. 2021. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffer, M.; Ayad, J.; Tungol, J.G.; MacDonald, R.; Dickey, N.; Venters, H. Improving transgender healthcare in the New York City correctional system. LGBT Health 2016, 3, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilty, J. I just wanted them to see me: Intersectional stigma and the health consequences of segregating Black, HIV + transwomen in prison in the US state of Georgia. Gend. Place Cult. 2020, 22, 1019–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, L.; Simpson, P.; Richters, J.; Donovan, B.; Grant, L.; Butler, T. Disclosing sexuality: Gay and bisexual men’s experiences of coming out, forced out, going back in and staying out of the ‘closet’ in prison. Cult. Health Sex. 2020, 22, 1222–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCauley, E.; Eckstrand, K.; Desta, B.; Bouvier, B.; Brockmann, B.; Brinkley-Rubinstein, L. Exploring healthcare experiences for incarcerated individuals who identify as transgender in a southern jail. Transgender Health 2018, 3, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harvey, T.D.; Keene, D.E.; Pachankis, J.E. Minority stress, psychosocial health, and survival among gay and bisexual men before, during, and after incarceration. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J.; Sexton, L. Same difference: The “dilemma of difference” and the incarceration of transgender prisoners. Law Soc. Inq. 2016, 41, 616–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschi, T.; Rees, J.; Klein, E. “Coming out” of prison: An exploratory study of LGBT elders in the criminal justice system. J. Homosex. 2016, 63, 1277–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.; Simpson, P.L.; Butler, T.G.; Richters, J.; Yap, L.; Donovan, B. You’re a woman, a convenience, a cat, a poof, a thing, an idiot: Transgender women negotiating sexual experiences in men’s prisons in Australia. Sexualities 2017, 20, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochdorn, A.; Faleiros, V.P.; Valerio, P.; Vitelli, R. Narratives of transgender people detained in prison: The role played by the utterances “not” (as a feeling of hetero-and auto-rejection) and “exist” (as a feeling of hetero-and auto-acceptance) for the construction of a discursive self. A suggestion of goals and strategies for psychological counseling. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jenness, V.; Fenstermaker, S. Agnes goes to prison: Gender authenticity, transgender inmates in prisons for men, and pursuit of “the real deal”. Gend. Soc. 2014, 28, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White-Hughto, J.M.; Clark, K.A.; Altice, F.L.; Reisner, S.L.; Kershaw, T.S.; Pachankis, J.E. Creating, reinforcing, and resisting the gender binary: A qualitative study of transgender women’s healthcare experiences in sex-segregated jails and prisons. Int. J. Prison. Health 2018, 14, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, R.; Oswin, N. Trans embodiment in carceral space: Hypermasculinity and the US prison industrial complex. Gend. Place Cult. 2015, 22, 1269–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRI & APT [Penal Reform International & Association for the Prevention of Torture]. LGBTI Persons Deprived of Their Liberty: A Framework for Preventative Monitoring; Penal Reform International: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, N.; McAlister, S.; Serisier, T. Out on the Inside. The Rights, Experiences and Needs of LGBT People in Prison; Irish Penal Reform Trust: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shabazz, R. So high you can’t get over it, so low you can’t get under it: Carceral spatiality and black masculinities in the United States and South Africa. Souls 2009, 11, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, F. Discrimination against LGBT people triggers health concerns. Lancet 2014, 383, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hout, M.C.; Kewley, S.; Hillis, A. Contemporary transgender health experience and health situation in prisons: A scoping review of extant published literature (2000–2019). Int. J. Transgender Health 2020, 21, 258–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moagi, M.M.; Der Wath, A.E.V.; Jiyane, P.M.; Rikhotso, R.S. Mental health challenges of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people: An integrated literature review. Health SA Gesondheid 2021, 26, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayhan, C.H.B.; Bilgin, H.; Uluman, O.T.; Sukut, O.; Yilmaz, S.; Buzlu, S. A systematic review of the discrimination against sexual and gender minority in health care settings. Int. J. Health Serv. 2020, 50, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimble, P.E. Ignored LGBTQ prisoners: Discrimination, rehabilitation, and mental health services during incarceration. LGBTQ Policy J. 2019, 9, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada, R.; Marksamer, J. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young people in state custody: Making the child welfare and juvenile justice systems safe for all youth through litigation, advocacy, and education. Temp. L. Rev. 2006, 79, 415. [Google Scholar]

- Kahle, L.L.; Rosenbaum, J. What staff need to know: Using elements of gender-responsive programming to create safer environments for system-involved LGBTQ girls and women. Crim. Justice Stud. 2021, 34, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughto, J.M.; Clark, K.A. Designing a transgender health training for correctional health care providers: A feasibility study. Prison J. 2019, 99, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevelius, J.; Jenness, V. Challenges and opportunities for gender-affirming healthcare for transgender women in prison. Int. J. Prison. Health 2017, 13, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Hout, M.C.; Crowley, D. The “double punishment” of transgender prisoners: A human rights-based commentary on placement and conditions of detention. Int. J. Prison. Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Code | Query | PsycINFO | MEDLINE | CINAHL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | LGBT * OR gay OR homosexual OR ‘sexual minority’ OR transgender OR bisexual OR lesbian | 15,436 | 18,233 | 15,434 |

| S2 | ‘mental health’ OR psychosocial | 89,446 | 46,588 | 17,001 |

| S3 | prisons OR jail OR penitentiary OR correctional OR ‘penal institution’ or lockup OR prisoner or inmate OR convict OR criminal OR offender OR incarcerated | 55,302 | 36,734 | 8166 |

| S4 | opinions OR views OR perceptions OR experiences OR qualitative | 637,325 | 908,616 | 21,861 |

| S5 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 | 281 | 89 | 59 |

| CASP Criteria | Harvey et al. (2021) | Hochdorn et al. (2018) | Jaffer et al. (2016) | Janness and Fenster-Maker (2014) | Kilty (2020) | Maashi et al. (2016) | McCauley et al. (2018) | Rosenberg and Oswin (2015) | Sumner and Sexton (2016) | White-Hughto et al. (2018) | Wilson et al. (2017) | Yap et al. (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Clear statement of aims | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2. Appropriate methodology | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 3. Appropriate research design | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 4. Appropriate recruitment strategy | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 5. Appropriate data collection methods | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 6. Research relationships considered | CT | CT | N | N | Y | CT | Y | CT | CT | Y | Y | CT |

| 7. Consider ethical issues | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | CT | CT | CT | Y | CT | CT |

| 8. Rigorous analysis | Y | Y | CT | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 9. Clear findings | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 10. Value of the research | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Citation and Country | Aim | Sample | Methods | Main Results | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvey et al. (2021) USA [25] | To examine previously incarcerated gay and bisexual male (GBM) experiences of minority stress and management of their sexual identity. | Formerly incarcerated GBM in New York City (n = 20). Mean age 40.2 (±12.4) | Semi-structured, in-depth interviews. | Findings document the ways in which this population manages their sexual identities in the context of minority stress alongside the associated psychosocial health risks. Themes include minority stress: (1) as catalyzing incarceration-related experiences, (2) as motiving identity management techniques and (3) as a determinant to re-entry support and sexual expression after incarceration. | Recommendations are for changes to public health policy and practice. These changes will better serve the needs of incarcerated GBM and will inform practice that aims to prevent incarceration in the first place. |

| Hochdorn et al. (2018) Italy/Brazil [29] | To investigate how the discursive positioning among the ‘Self’ and the ‘Other’ might promote the internalization of positive and/or negative attitudes toward the self in trans women. | Transgender women detained in prison contexts in Italy and Brazil. Aged 24–51 years | In-depth interviews | The findings demonstrated language differences amongst transgender inmates in Brazilian and Italian samples. Additionally, in Brazil, transgender women assumed masculine-driven behavior due to a common imprisonment with cis-gender men. Transgender women in Italy however are detained in protected sections, where they are allowed to wear female clothing and continue hormonal treatments. Finally, transgender inmates in Italy suffered more violence in a female sector when compared to exclusively male jails. | The needs of transgender people should receive special attention as they vary greatly to their cis gender inmates. Psychological counseling with transgender women should pay particular attention to the psycho-social issues of this population. |

| Jaffer et al. (2016) USA [21] | To review and evaluate the provision of care for transgender people in the New York City prison system. | Transgender people housed in jail facilities (n = 27) Age range—n/a | A brief in-person survey | The dominant concern of transgender people in prison was their inability to obtain hormone therapy. Almost all participants felt there was a lack of familiarity and sensitivity to their specific health and other concerns. | Opportunities exist to deliver dedicated services to the transgender population in prison. Participants recommended hiring clinical staff with transgender experience or designating qualified transgender healthcare providers. All particiapants emphasized the need for specific transgender housing. |

| Jenness and Fenstermaker (2014) USA [30] | To explore how gender is accomplished by trans prisoners in prisons for men. | Transgender inmates (n = 315). Age range—n/a | Semi-structured interviews | In prison, transgender people engage in behaviors that constitute what the authors refer to as the pursuit of gender authenticity. There exists a gender order for participants that underpins prison life for transgender inmates. | Further research necessary looking specifically at transgender women in order to understand more about the context of living as transgneder in prisons. |

| Kilty (2020) USA [22] | To explore how stigma emerges in the prison environment and to explore the ways that HIV and transgender stigma are linked to harmful practices. | Black HIV-positive transgender women (n = 10). Age range—n/a | Interviews, face-to-face. | Participants revealed that the many different forms of stigma resulted in a type of coercive practice that resulted in the suppression of their gender identity. They also spoke of the inappropriate use of solitary confinement and their expereinces of often being denied access to HIV medication and hormone replacement therapies (HRT). | In order to help curb transgender and HIV stigma and discrimination it is essential to significantly improve correctional staff members and health care providers knowledge about HIV and transgender issues. Mandatory transgender and HIV education classes and sensitivity training would help to build cultural and clinical competence. |

| Maashi et al. (2016) USA [27] | To explore the experiences of formerly incarcerated LGBT elders before, during, and after prison. | LGBT elders (n = 10). Aged 50–65 years. | Focus groups and individual interviews | A core theme that emerged concerned LGBT elders ongoing coming-out process that is concurrently being managed via multiple stigmatized identities. These findings increase our awareness of an often neglected population of LGBT who are older and in prison. | Formerly incarcerated LGBT elders should be included in future recommendations for services and policy reform in carceral settings. |

| McCauley et al. (2018) USA [28] | To document the health-related experiences and needs of transgender women of color in prison. | Transgender women of color (n = 10) Age range—n/a | Semi-structured interviews | Participants experienced high levels of abuse and harassment. This led to mental health issues which were exacerbated by the lack of access to hormone treatments. | Policy changes necessary to address housing issues, and to improve access to healthcare for transgender women in prison. Training is required for prison staff to better understand the unique needs and experiences of transgender people. |

| Rosenberg and Oswin (2015) USA [32] | To examine the experiences of incarcerated transgender people. | Trans feminine inmates (n = 23) Aged 19–50 years. | In-depth questionnaires | Participants experienced harsh conditions of confinement. Part of the diffculty with carceration for this population is having to cope with hypermasculine and heteronormative prison environment. | None identified. |

| Sumner and Sexton (2016) USA [26] | To examine the “dilemma of difference” transgender prisoners face within a sex-segregated prison system. | Transgender prisoners (n = 10), prisoners (n = 27) and prison staff (n = 20) Mean Prisoner Age-41 Years | In-depth qualitative interviews and focus groups. | Transgender prisoners are and should be treated like everyone else, despite their unique situations. Themes addressed included the differences and meaning of being transgnder in prison. The consequences of these differences are also addressed. | Need for provision of gender specific clothing, housing assignments, and treatment. In order to esure this, the institution must understand the point of difference for transgender prisoners in the context of gender as opposed to sexuality. |

| White-Hughto et al. (2018) USA [31] | To explore the healthcare experiences and interactions with correctional healthcare providers of incarcerated transgender women. | Transgender Women (n = 20) Mean age 36.9 years (SD ¼ 10.0) | Semi-structured interviews. | Participants described an institutional culture in which their feminine identity was not recognized. They also described the ways in which prison policies acted as a form of structural stigma. Some participants attributed healthcare barriers to bias whilst others understood it as provider’s limited knowledge of transgender issues. These barriers to appropriate physical, mental, and gender transition-related healthcare negatively impacted participants’ health while incarcerated | Delivery of healthcare to incarcerated transgender individuals is under researched. Access to gender affirmative care for incarcerated transgender communities can be achived throught educational and policy interventions. |

| Wilson et al. (2017) Australia [28] | To examine the sexual experiences of trans women in men’s prisons specifically addressing sexual safety. | Transgender Women (n = 7). Aged 20 to 47 years. | Semi-structured interviews. | Whilst there were some rape experiences described by particpants, accounts of sexual activity were not always physically violent and issues of consent were not always clearly defined. | There is a need to look at ways to prevent the incarceration of trans women. In the absence of this, recomendations are needed to explore ways in which trans women can be better supported in the prison setting. |

| Yap et al. (2020) Australia [23] | To explore the concept of coming out in prison. | Prisoners and one ex-prisoner who self-identified as gay, homosexual or bisexual men (n = 13). Aged 20–59 years. | In-depth interviews | Respondents were required to continuously manage their sexual identities and disclosure to different audiences while incarcerated. Findings suggest that the heteronormative prison environment and its’ consequences, apply considerable pressure on gay and bisexual men, around mangaing the disclosure of their sexual identity. | None identified. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donohue, G.; McCann, E.; Brown, M. Views and Experiences of LGBTQ+ People in Prison Regarding Their Psychosocial Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9335. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179335

Donohue G, McCann E, Brown M. Views and Experiences of LGBTQ+ People in Prison Regarding Their Psychosocial Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(17):9335. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179335

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonohue, Gráinne, Edward McCann, and Michael Brown. 2021. "Views and Experiences of LGBTQ+ People in Prison Regarding Their Psychosocial Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 17: 9335. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179335

APA StyleDonohue, G., McCann, E., & Brown, M. (2021). Views and Experiences of LGBTQ+ People in Prison Regarding Their Psychosocial Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9335. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179335