Systematic Review on Mentalization as Key Factor in Psychotherapy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Operationalization of Mentalization

1.2. Concepts of Psychotherapy Process Factors

2. Method

2.1. Literature Search and Study Selection

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

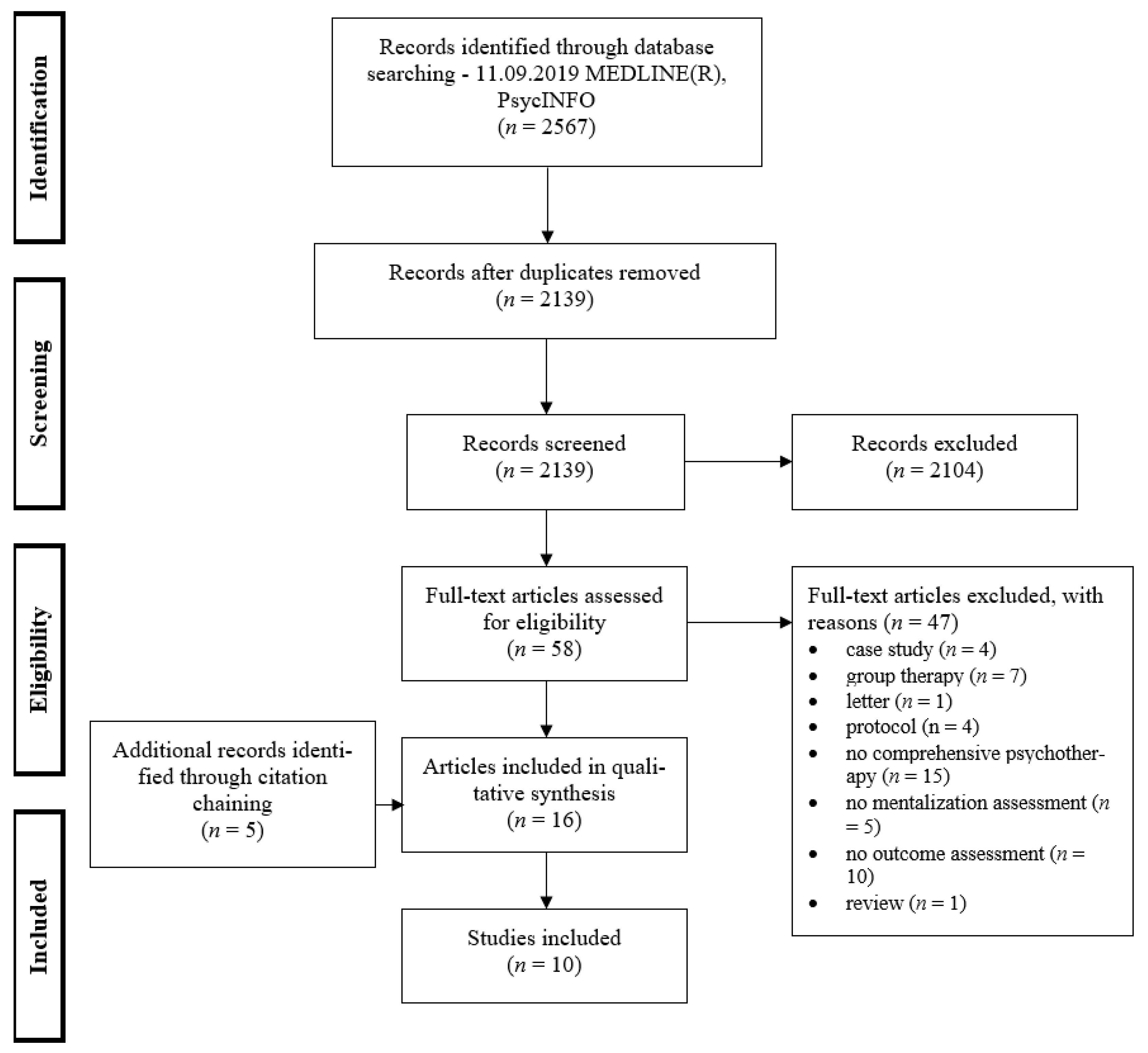

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. The Mentalization Variable in the Psychotherapy Process

3.4. Mentalization as Predictor

3.5. Mentalization as Moderator

3.6. Mentalization as Mediator

3.7. Mentalization Change

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bateman, A.; Fonagy, P. Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A.; Fonagy, P. Randomized Controlled Trial of Outpatient Mentalization-Based Treatment Versus Structured Clinical Management for Borderline Personality Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 8, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A.; Fonagy, P. Mentalization Based Treatment for Personality Disorders: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed.; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 9780191669910. [Google Scholar]

- Luyten, P.; Malcorps, S.; Fonagy, P.; Ensink, K. Assessment of Mentalizing. In Handbook of Mentalizing in Mental Health Practice, 2nd ed.; Bateman, A., Fonagy, P., Eds.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 37–62. ISBN 9781615372508. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P. Attachment theory approach to treatment of the difficult patient. Bull. Menn. Clin. 1998, 62, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P.; Steele, H.; Steele, M. Maternal representations of attachment during pregnancy predict the organization of infant-mother attachment at one year of age. Child Dev. 1991, 62, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Bateman, A. The development of borderline personality disorder—A mentalizing model. J. Pers. Disord. 2008, 22, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonagy, P.; Steele, M.; Steele, H.; Moran, G.S.; Higgitt, A.C. The capacity for understanding mental states: The reflective self in parent and child and its significance for security of attachment. Infant Ment. Health J. 1991, 12, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Kern, M.; Buchheim, A.; Hörz, S.; Schuster, P.; Doering, S.; Kapusta, N.; Taubner, S.; Tmej, A.; Rentrop, M.; Buchheim, P.; et al. The relationship between personality organization, reflective functioning, and psychiatric classification in borderline disorder. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2010, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fonagy, P.; Target, M. Playing with reality: III. The persistence of dual psychic reality in borderline patients. Int. J. Psychoanal. 2000, 81, 853–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skårderud, F. Eating one’s words, part I: ‘Concretised metaphors’ and reflective function in anorexia nervosa—An interview study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2007, 15, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skårderud, F. Eating one’s words, part II: The embodied mind and reflective function in anorexia nervosa—Theory. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2007, 15, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skårderud, F. Eating one’s words: Part III. Mentalisation-based psychotherapy for anorexia nervosa—An outline for a treatment and training manual. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2007, 15, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemma, A.; Target, M.; Fonagy, P. The development of a brief psychodynamic intervention (dynamic interpersonal therapy) and its application to depression: A pilot study. Psychiatry 2011, 74, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Markowitz, J.C.; Meehan, K.B. Does depressive state influence reported attachment status? J. Clin. Psychiatry 2009, 70, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robinson, P.; Hellier, J.; Barrett, B.; Barzdaitiene, D.; Bateman, A.; Bogaardt, A.; Clare, A.; Somers, N.; O’Callaghan, A.; Goldsmith, K.; et al. The NOURISHED randomised controlled trial comparing mentalisation-based treatment for eating disorders (MBT-ED) with specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM-ED) for patients with eating disorders and symptoms of borderline personality disorder. Trials 2016, 17, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Staun, L.; Kessler, H.; Buchheim, A.; Kächele, H.; Taubner, S. Mentalisierung und chronische Depression. Psychotherapeut 2010, 55, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubner, S.; Kessler, H.; Buchheim, A.; Kächele, H.; Staun, L. The role of mentalization in the psychoanalytic treatment of chronic depression. Psychiatry 2011, 74, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P. A developmental, mentalization-based approach to the understanding and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Dev. Psychopathol. 2009, 21, 1355–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyten, P.; Fonagy, P.; Lowyck, B.; Vermote, R. Assessment of mentalization. In Handbook of Mentalizing in Mental Health Practice, 1st ed.; Bateman, A., Fonagy, P., Eds.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P.; Bateman, A. Introduction. In Handbook of Mentalizing in Mental Health Practice, 2nd ed.; Bateman, A., Fonagy, P., Eds.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 3–20. ISBN 9781615372508. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.G.; Fonagy, P.; Bateman, A. Mentalizing in Clinical Practice, 1st ed.; American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; ISBN 9781585628360. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.G. Restoring Mentalizing in Attachment Relationships: Treating Trauma with Plain Old Therapy, 1st ed.; American Psychiatric Pub: Arlington, VA, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781585624188. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P.; Campbell, C.; Allison, E. Therapeutic Models. In Handbook of Mentalizing in Mental Health Practice, 2nd ed.; Bateman, A., Fonagy, P., Eds.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 169–180. ISBN 9781615372508. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.G.; Fonagy, P. The Handbook of Mentalization-Based Treatment; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Khorashad, B.S.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Roshan, G.M.; Kazemian, M.; Khazai, L.; Aghili, Z.; Talaei, A.; Afkhamizadeh, M. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test: Investigation of Psychometric Properties and Test-Retest Reliability of the Persian Version. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 2651–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudden, M.; Milrod, B.; Target, M.; Ackerman, S.; Graf, E. Reflective functioning in panic disorder patients: A pilot study. J. Am. Psychoanal. Assoc. 2006, 54, 1339–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P.; Moulton-Perkins, A.; Lee, Y.-W.; Warren, F.; Howard, S.; Ghinai, R.; Fearon, P.; Lowyck, B. Development and Validation of a Self-Report Measure of Mentalizing: The Reflective Functioning Questionnaire. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyten, P.; Mayes, L.C.; Nijssens, L.; Fonagy, P. The parental reflective functioning questionnaire: Development and preliminary validation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rutherford, H.J.V.; Booth, C.R.; Luyten, P.; Bridgett, D.J.; Mayes, L.C. Investigating the association between parental reflective functioning and distress tolerance in motherhood. Infant Behav. Dev. 2015, 40, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hayden, M.C.; Müllauer, P.K.; Gaugeler, R.; Senft, B.; Andreas, S. Improvements in mentalization predict improvements in interpersonal distress in patients with mental disorders. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 2276–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, G.S.; van Loenhout, Z.; van der Ark, L.A.; Bekker, M.H.J. Is reduction of symptoms in eating disorder patients after 1 year of treatment related to attachment security and mentalization? Eat. Disord. 2018, 26, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A.E. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kazdin, A.E. Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychother. Res. 2009, 19, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, H.C.; Wilson, G.T.; Fairburn, C.G.; Agras, W.S. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2002, 59, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambless, D.L.; Hollon, S.D. Defining empirically supported therapies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 66, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P. Thinking about thinking: Some clinical and theoretical considerations in the treatment of a borderline patient. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1991, 72, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antonsen, B.T.; Johansen, M.S.; Rø, F.G.; Kvarstein, E.H.; Wilberg, T. Is reflective functioning associated with clinical symptoms and long-term course in patients with personality disorders? Compr. Psychiatry 2016, 64, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gullestad, F.S.; Johansen, M.S.; Høglend, P.; Karterud, S.; Wilberg, T. Mentalization as a moderator of treatment effects: Findings from a randomized clinical trial for personality disorders. Psychother. Res. 2013, 23, 674–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnevik, E.; Wilberg, T.; Urnes, O.; Johansen, M.; Monsen, J.T.; Karterud, S. Psychotherapy for personality disorders: Short-term day hospital psychotherapy versus outpatient individual therapy—A randomized controlled study. Eur. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J.P.; Milrod, B.; Gallop, R.; Solomonov, N.; Rudden, M.G.; McCarthy, K.S.; Chambless, D.L. Processes of therapeutic change: Results from the Cornell-Penn Study of Psychotherapies for Panic Disorder. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomonov, N.; Aafjes van-Doorn, K.; Lipner, L.M.; Gorman, B.S.; Milrod, B.; Rudden, M.G.; Chambless, D.L.; Barber, J.P. Panic-Focused Reflective Functioning and Comorbid Borderline Traits as Predictors of Change in Quality of Object Relations in Panic Disorder Treatments. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2019, 49, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, T.; Nazzaro, M.P.; Damiani, R.; Genova, F.; Gazzillo, F.; Lingiardi, V. Mentalization as a predictor of psychoanalytic outcome: An empirical study of transcribed psychoanalytic sessions through the lenses of a computerized text analysis measure of reflective functioning. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2018, 35, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressi, C.; Fronza, S.; Minacapelli, E.; Nocito, E.P.; Dipasquale, E.; Magri, L.; Lionetti, F.; Barone, L. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy with mentalization-based techniques in major depressive disorder patients: Relationship among alexithymia, reflective functioning, and outcome variables—A Pilot study. Psychol. Psychother. 2016, 90, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeblad, A.; Falkenström, F.; Holmqvist, R. Reflective functioning as predictor of working alliance and outcome in the treatment of depression. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 84, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Kern, M.; Doering, S.; Taubner, S.; Hörz, S.; Zimmermann, J.; Rentrop, M.; Schuster, P.; Buchheim, P.; Buchheim, A. Transference-focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Change in reflective function. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tmej, A.; Fischer-Kern, M.; Doering, S.; Alexopoulos, J.; Buchheim, A. Changes in Attachment Representation in Psychotherapy: Is Reflective Functioning the Crucial Factor? Z. Psychosom. Med. Psychother. 2018, 64, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doering, S.; Hörz, S.; Rentrop, M.; Fischer-Kern, M.; Schuster, P.; Benecke, C.; Buchheim, A.; Martius, P.; Buchheim, P. Transference-focused psychotherapy v. treatment by community psychotherapists for borderline personality disorder: Randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 196, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Karlsson, R.; Kermott, A. Reflective-functioning during the process in brief psychotherapies. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2006, 43, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elkin, I.; Shea, M.T.; Watkins, J.T.; Imber, S.D.; Sotsky, S.M.; Collins, J.F.; Glass, D.R.; Pilkonis, P.A.; Leber, W.R.; Docherty, J.P. National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. General effectiveness of treatments. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1989, 46, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.E.; Pulos, S.M. Comparing the process in psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral therapies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1993, 61, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, C.; Kaufhold, J.; Overbeck, G.; Grabhorn, R. The importance of reflective functioning to the diagnosis of psychic structure. Psychol. Psychother. 2006, 79, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taubner, S.; Schulze, C.I.; Kessler, H.; Buchheim, A.; Kächele, H.; Staun, L. Veränderungen der mentalisierten Affektivität nach 24 Monaten analytischer Psychotherapie bei Patienten mit chronischer Depression. Psychother. Forum 2015, 20, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertuck, E.A.; Mergenthaler, E.; Target, M.; Levy, K.N.; Clarkin, J.F. Development and criterion validity of a computerized text analysis measure of reflective functioning. Psychother. Res. 2012, 22, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milrod, B.L. Manual of Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; ISBN 0-88048-871-9. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, S.; Moscovitz, S.; Lundin, J.; Helm, F.; Jemerin, J.; Gorman, B. Evaluating the outcomes of psychotherapies: The Personality Health Index. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2011, 28, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katznelson, H.; Falkenström, F.; Daniel, S.I.F.; Lunn, S.; Folke, S.; Pedersen, S.H.; Poulsen, S. Reflective functioning, psychotherapeutic alliance, and outcome in two psychotherapies for bulimia nervosa. Psychotherapy 2020, 57, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antonsen 2016 | Barber 2020 | Boldrini 2018 | Bressi 2016 | Ekeblad 2016 | |

| Publication | [39,40,41] | [42,43] | [44] | [45] | [46] |

| (NCT00353470) | |||||

| Country | Norway | USA | USA | Italy | Sweden |

| Study type | RCT | RCT | Pre–post n,d | Pre–post n | RCT |

| N patients | 37 a | 138 a | 27 | 24 | 85 |

| Mean Age | 31.6 (SD 7.7) | Not reported | 33 (range: 20–70) | 44.63 (SD 5.88) | 34.2 (SD 10.82) |

| Female % | 75 | 62.3 | 48 | 45.83 | 68.8 |

| Diagnoses | BPD, AvPD | PD | Mixed e | MDD | MDD |

| Intervention | Mixed b | CBT, PFPP | Psychoanalytic treatment | STMBP | CBT, IPT |

| N Therapist | 32 | 24 | 8 | 2 | 34 |

| Duration | 65 (SD 60) sessions | 19–24 sessions (twice-weekly) | 366 sessions (range: 120–2836) | 40 sessions | 14 sessions |

| Outcome | SCL-90-R | PDSS | GAF, PHI | GAF, HAM-D | BDI-II |

| measurement points | T0: baseline | T0: baseline | T1: first 4 sessions | T0: baseline | Before every session |

| T1: 8 months | T1: week 1 | T2: 4 sessions | T1: 40 weeks (end) | ||

| T2: 18 months | T2: week 5 | after 1 month | T2: 1 year follow-up | ||

| T3: 36 months | T3: week 10 | T3: 1 month before termination | |||

| T4: 72 months | T4: at termination | T4: last 4 sessions | |||

| Mentalization | RFS (AAI) | RFS (AAI-short c), PSRF (PSRF-I) | CRF (sessions) | RFS (AAI) | RFS, DSRF (AAI-short f) |

| measurement points | T0: baseline | TO: baseline | T1: first 4 sessions | T0: baseline | T0: baseline |

| T1: 36 months | T1: week 5 | T2: 4 sessions | T1: 40 weeks (end) | ||

| T2: at termination | after 1 month | T2: 1 year follow-up | |||

| T3: 4 sessions in the middle phase | |||||

| T4: 1 month before termination | |||||

| T5: last 4 sessions | |||||

| Outcome | Significant improvement T0–T3 (d = 1.0) | Improvement T0–T4 | Significant improvement T1–T5 | Significant improvement T0–T3 | Significant improvement session 1–14 (CBT: d = 1.15; IPT: d = 1.49) |

| Mentalization change | Not reported | RFS did not improv;e PSRF significantly improved in PFPP, not in CBT | No significant CRF change | Small, non- significant RFS change in therapy (T0-T1); significant RFS change at follow-up (T1-T2) | Not examined |

| Mentalization-Outcome-relation | a. RFS is not a significant predictor of outcome | Early change in RFS is not significantly associated with outcome change | Early CRF significantly predicts outcome change | RFS significantly predicts outcome change | RFS/DSRF significantly predicts outcome change |

| b. RFS is a significant moderator of treatment effects (low RF patients had better outcomes in outpatient individual therapy compared to control condition) | Early change in PSRF was associated with significantly greater change in outcome (the association was stronger for CBT) | ||||

| Fischer-Kern 2015 | Karlsson 2006a | Karlsson 2006b | Müller 2006 | Taubner 2015 | |

| Publication | [9,47,48,49] | [50,51] | [50,52] | [53] | [18,54] |

| Country | Austria, Germany | USA | USA | Germany | Germany |

| Study type | RCT | RCT (archival) | Pre–post (archival) | Pre–post | Pre–post |

| N patients | 92 | 64 | 30 | 24 | 20 |

| Mean Age | 27.7 (SD 7.3); range: 18–51 | 35 (SD 8.5) | 50 (range: 20–81 years) | 28 (SD 10) | 39.2 (SD 12.7) |

| Female % | 100 | 70 | 66.6 | 70.5 | 80 |

| Diagnoses | BPD | MDD | Mixed i | Mixed j | MDD |

| Intervention | TFP, mixed g | CBT, IPT | BPDT | Mixed k | psychoanalytic treatment |

| N Therapist | 67 | 18 | 15 | not reported | 16 |

| Duration | at least 1 year h | 16.2 (SD 2.5) sessions | 15.8 (SD 1.35) sessions | 3 months | 227,95 (SD 88,48) hours |

| Outcome | STIPO | BDI, HSCL-90, HRSD | HSCL-90: GSI, BPRS | SCL-90-R | BDI, SCL-90-R |

| measurement points | T0: pre-treatment | T1: session 4 | T1: session 1 | T0: baseline | T0: pre-treatment |

| T1: 1 year after start of therapy | T2: session 12 | T2: session 5 | T1: end of treatment | T1: 24 months in treatment | |

| T3: session 14 | T2: 36 months in treatment | ||||

| Mentalization | RFS (AAI) | RFS (sessions) | RFS (sessions) | RFS (AAI-shortc) | RFS (AAI) |

| measurement points | T0: pre-treatment | T1: session 4 | T1: session 1 | T1: first week in treatment | T0: pre-treatment |

| T1: 1 year after start of therapy | T2: session 12 | T2: session 5 | T1: 24 months in treatment | ||

| T3: session 14 | |||||

| Outcome | Significant improvement T0–T1 | Significant improvement T1–T2 | Significant improvement T1–T3 | Improvement T0–T1 | Significant improvement session 1–14 (GSI: d = 1.64; BDI: d = 2.1) |

| Mentalization change | RFS significantly improved in TFP, but not in the control condition | Significant RFS decrease (T1–T2) | No significant RFS change | Not examined | Significant RFS increase (T0–T1) |

| Mentalization-Outcome-relation | RFS improvement significantly predicts outcome change | Process correlates associated with low/high RFS predicted poor/good outcome | RFS is partly related to outcome change | RFS significantly predicts outcome change | RFS significantly predicts outcome change for BDI, but not for GSI |

| RFS change had no significant effect on outcome |

| RFS | T1 | T2 | T1 Control | T1 Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonsen 2016 | 3.5 (SD 1.7) | n/r | 3.0 (SD 1.5) a | n/r |

| Bressi 2016 | 4.00 (SD 2.09) | 4.13 (SD 1.80) | ||

| Ekeblad 2016 | 2.62 (SD 1.22) | n/r | ||

| Fischer-Kern 2015 | 2.82 (SD 1.29) | 3.32 (SD 0.99) | 2.80 (SD 0.96) b | 2.92 (SD 1.00) |

| Karlsson 2006a | 5.13 (SD 1.37) | 3.99 (SD 1.35) | 3.79 (SD 1.29) c | 3.41 (SD 1.26) |

| Karlsson 2006b | 4.62 (SD 1.39) | 4.37 (SD 0.82) | ||

| Müller 2006 | median: 3 (range: 1–5) | n/r | ||

| Taubner 2015 | 3.85 (SD 0.94) | 4.38 (SD 0.93) | ||

| Barber 2020 | 4.04 (SD 1.23) | 4.42 (SD 1.27) | 4.39 (SD 1.32) d | 4.37 (SD 1.13) |

| CRF | T1 | T2 | ||

| Boldrini 2018 | 29.09 (SD 7.75) | 27.25 (SD 9.00) | ||

| DSRF | T1 | |||

| Ekeblad 2016 | 2.37 (SD 0.98) | |||

| PSRF | T1 | T2 | T1 Control | T1 Control |

| Barber 2020 | 3.50 (SD 1.19) | 4.43 (SD 1.38) | 3.68 (SD 1.21) d | 3.68 (SD 1.10) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lüdemann, J.; Rabung, S.; Andreas, S. Systematic Review on Mentalization as Key Factor in Psychotherapy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179161

Lüdemann J, Rabung S, Andreas S. Systematic Review on Mentalization as Key Factor in Psychotherapy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(17):9161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179161

Chicago/Turabian StyleLüdemann, Jonas, Sven Rabung, and Sylke Andreas. 2021. "Systematic Review on Mentalization as Key Factor in Psychotherapy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 17: 9161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179161

APA StyleLüdemann, J., Rabung, S., & Andreas, S. (2021). Systematic Review on Mentalization as Key Factor in Psychotherapy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179161