Barriers and Facilitators of Breast Cancer Screening amongst Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Women in South Western Sydney: A Qualitative Explorative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analysis

2.5. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Healthcare and Illness-Related Experiences Influencing Screening

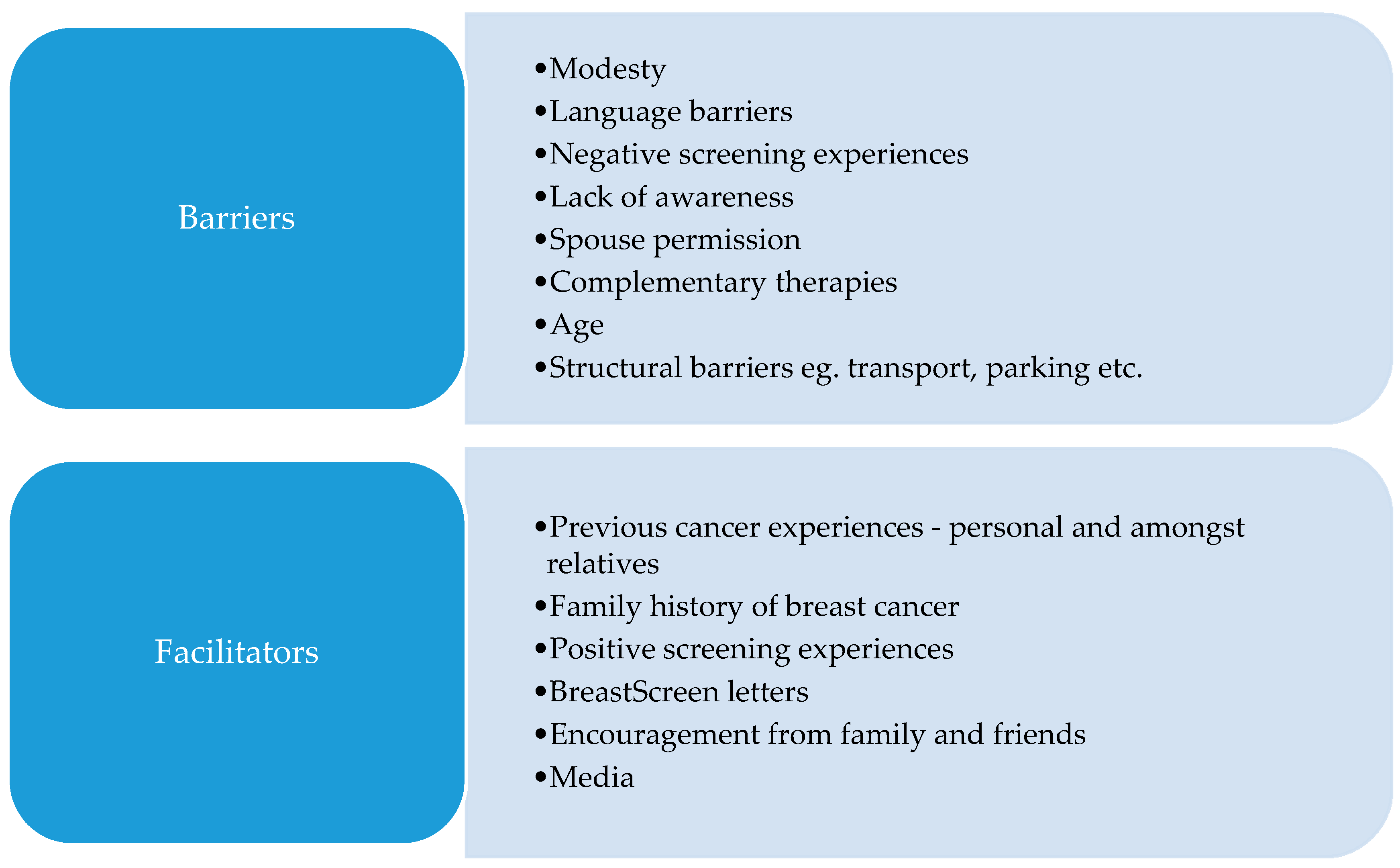

3.3. Cultural Barriers towards Screening Attendance

3.4. Personal Barriers towards Mammography

3.5. General Facilitators to Screening

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Schedule

- Have you had any breast cancer screening in the past?

- How many times have you attended?

- When did you have that screening?

- Why did you decide to have that screening?

- Were there any difficulties you had to overcome to have the screening?

- Who advised you to have screening?

- Why did you decide not to have that screening?

- What healthcare encounters have you had in the past that may have influenced your screening decision?

- What is the purpose of screening?

- How regularly mammograms need to be repeated?

- How do you feel about getting breast cancer screening in the future?

- What information and support would encourage you to participate in future screening?

- How clear are the messages you see about breast cancer screening?

- What do you think could be done to increase cancer screening participation in general?

- Is there anything you would like to ask me?

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer Data in Australia [Internet]; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer-data-in-australia (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2019 [Internet]; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/8c9fcf52-0055-41a0-96d9-f81b0feb98cf/aihw-can-123.pdf.aspx?inline=true (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia: Actual incidence data from 1991 to 2009 and mortality data from 1991 to 2010 with projections to 2012. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 9, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsbury, D.E.; Yap, S.; Weber, M.F.; Veerman, L.; Rankin, N.; Banks, E.; Canfell, K.; O’Connell, D.L. Health services costs for cancer care in Australia: Estimates from the 45 and Up Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BreastScreen NSW. Overdiagnosis [Internet]. Sydney (NSW). 2018. Available online: https://www.breastscreen.nsw.gov.au/about-screening-mammograms/screening-limitations/overdiagnosis (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Breast Screen NSW. Am I Eligible for a Screening Mammogram? [Internet]. Sydney (NSW). 2018. Available online: https://www.breastscreen.nsw.gov.au/about-screening-mammograms/am-i-eligible-for-a-mammogram/ (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- McCarthy, E.P.; Burns, R.B.; Freund, K.M.; Ash, A.S.; Shwartz, M.; Marwill, S.L.; Moskowitz, M.A. Mammography Use, Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis, and Survival Among Older Women. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2000, 48, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helvie, M.; Chang, J.; Hendrick, R.; Banerjee, M. Reduction in late-stage breast cancer incidence in the mammography era: Implications for overdiagnosis of invasive cancer. Cancer 2014, 120, 2649–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taplin, S.H.; Ichikawa, L.; Yood, M.U.; Manos, M.M.; Geiger, A.M.; Weinmann, S.; Gilbert, J.; Mouchawar, J.; Leyden, W.A.; Altaras, R.; et al. Reason for Late-Stage Breast Cancer: Absence of Screening or Detection, or Breakdown in Follow-up? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004, 96, 1518–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Australian Government Department of Health. The Australian Health System [Internet]; Australian Government Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/about-us/the-australian-health-system (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Cancer Council. Cancer Care and Your Rights [Internet]; Cancer Council Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://www.cancercouncil.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CANCER1.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Australian Government, Cancer Australia. Breast Screening Rates [Internet]; Cancer Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/screening/breast-screening-rates/breast-screening-rates (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- South Western Sydney Primary Health Network. SWSPHN: Cancer Screening Project Overview and Update; South Western Sydney Primary Health Network: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Breast Cancer [Internet]; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/breast-cancer/en/ (accessed on 19 July 2019).

- South Western Sydney Primary Health Network. Multicultural Health [Internet]; South Western Sydney Primary Health Network: Sydney, Australia, 2018; Available online: http://www.swsphn.com.au/multiculturalhealth (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016 Census QuickStats: Sydney-South West [Internet]; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2017. Available online: https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/127?opendocument (accessed on 19 July 2019).

- Rechel, B. Migration and Health in the European Union; McGraw Hill/Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, M.; Kwok, C.; Lee, M. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of routine breast cancer screening practices among migrant-Australian women. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 42, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phillipson, L.; Larsen-Truong, K.; Jones, S.; Pitts, L. Improving Cancer Outcomes among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities: A Rapid Review [Internet]; Sax Institute: Sydney, Australia, 2012; Available online: https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Improving-cancer-outcomes-among-CALD-communities-230413v2.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2019).

- McBride, K.A.; Sonego, S.; MacMillan, F. Community and Primary Care Perceptions on Cervical and Breast Screening Participation among CALD Women in the Nepean Blue Mountains Region; Wentworth Healthcare: Penrith, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, C.; Endrawes, G.; Lee, C. Cultural Beliefs and Attitudes about Breast Cancer and Screening Practices among Arabic Women in Australia. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Bogdan, R.; De Vault, M. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research. Encyclopaedia of Statistics in Behavioural Science; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health 2018. Australia’s Health Series no. 16. AUS 221 [Internet]; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2018. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/f3ba8e92-afb3-46d6-b64c-ebfc9c1f945d/aihw-aus-221-chapter-5-3.pdf.aspx (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- McBride, K.; Fleming, C.; George, E.; Steiner, G.; MacMillan, F. Double Discourse: Qualitative Perspectives on Breast Screening Participation among Obese Women and Their Health Care Providers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zapka, J.; Stoddard, A.; Costanza, M.; Greene, H. Breast cancer screening by mammography: Utilization and associated factors. Am. J. Public Health 1989, 79, 1499–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Azami-Aghdash, S.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Sheyklo, S.G.; Daemi, A.; Kolahdouzan, K.; Mohseni, M.; Moosavi, A. Breast Cancer Screening Barriers from the Womans Perspective: A Meta-synthesis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 3463–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexandraki, I.; Mooradian, A. Barriers Related to Mammography Use for Breast Cancer Screening among Minority Women. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2010, 102, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschel, K.; Thompson, B. Mammogram screening in Chile: Using mixed methods to implement health policy planning at the primary care level. Breast 2011, 20, S40–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentell, T.; Tsoh, J.; Davis, T.; Davis, J.; Braun, K. Low health literacy and cancer screening among Chinese Americans in California: A cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, L.; Harvey, E.; Hoffman-Goetz, L. Predicting Breast and Colon Cancer Screening among English-as-a-Second-Language Older Chinese Immigrant Women to Canada. J. Cancer Educ. 2010, 26, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawar, L. Barriers to breast cancer screening participation among Jordanian and Palestinian American women. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 17, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunsiji, O.O.; Kwok, C.; Fan, L.C. Breast cancer screening practices of African migrant women in Australia: A descriptive cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2017, 17, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Consedine, N.S.; Magai, C.; Neugut, A.I. The contribution of emotional characteristics to breast cancer screening among women from six ethnic groups. Prev. Med. 2004, 38, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Women Interviewed | n = 16 |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| 50–54 | 2 (13%) |

| 55–59 | 3 (19%) |

| 60–64 | 1 (6%) |

| 65–69 | 3 (19%) |

| 70–74 | 5 (31%) |

| 75–79 | 2 (13%) |

| Mean age | 65 ± 8.0 |

| CALD background | 16 (100%) |

| Italian | 8 (50%) |

| Lebanese | 1 (6%) |

| Maltese | 2 (13%) |

| Filipino | 1 (6%) |

| Croatian | 1 (6%) |

| Fijian | 1 (6%) |

| Uruguayan | 1 (6%) |

| Pakistani | 1 (6%) |

| Screening history | |

| Regular Screeners | 10 (63%) |

| Lapsed Screeners | 1 (6%) |

| Never Screeners | 5 (31%) |

| Emerging Theme | Excerpt Number | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer experiences | 2.1 | Sometimes through unfortunate experiences that women have gone through, it makes you stop and think as if—“No, I should still continue.” Because myself, I’ve had quite a few thoughts of like, “Oh, no, I’m not gonna do it anymore. What for? Wasting time, it’s uncomfortable.” We tend to have a lot of negativities in ourselves not to do it, but then when you hear an incident and it’s someone that you’ve dealt with for a long time, it sort of makes you change your way of thinking as if like, “No, I better continue”. (Italian woman, 57—Participant 2) |

| 2.2 | ....you hear friends having a problem with… this friend of mine, she’s in her 50s and she’s…gone through a chemo and all that and so you know that it’s an important thing to do. (Italian woman, 70—Participant 8) | |

| 2.3 | My neighbour, she’d done it [mammograms] and a couple of weeks later, she died from breast cancer. So what’s the point? They’re missing it already. (Lebanese woman, 53—Participant 1) | |

| 2.4 | My father had a bowel cancer, so I thought, “What if I have this sort of gene?” after losing my period so young and I have hysterectomy, [at] 36. (Italian woman, 67—Participant 5) | |

| 2.5 | I think lot of women, if they have… a family history of high risk in these malignant things, then of course… You would do it without even hesitation. (Italian woman, 57—Participant 2) | |

| 2.6 | I’m not gonna do... I’m not concerned at all because my history of my family… we don’t have cancer in the family at all. (Lebanese woman, 53—Participant 1) | |

| Screening experiences | 2.7 | I can’t fault the staff there that… do these tests. They’re very professional. …They know that it’s uncomfortable and …they’ve always—try and make you feel as comfortable as possible. (Italian woman, 57—Participant 2) |

| 2.8 | She wasn’t understanding that I was hurting. She said, “Gee, you’re a whinger,” and I thought, “Excuse me.” I said, “It hurts.” She says, “You’re not the only one.” I know I’m not the only one, but it hurts. (Italian woman, 67—Participant 5) | |

| 2.9 | No one is doing it in Liverpool because…. they do it rough. …and it doesn’t matter how many letters they send me. I’m not gonna go do it. (Lebanese woman, 53—Participant 1) |

| Emerging Theme | Excerpt Number | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| Modesty | 3.1 | It’s like you’re saying—it’s more—that invasive part of your body where you don’t really want people to go—so if there’s no—if you see no problem and you think that—okay, I’m fine. Why go there? (Italian woman, 56—Participant 15) |

| 3.2 | First of all, it’s humiliating. Okay, she’s a woman, all right, but it’s still a stranger. I don’t do that, not even with my bestest friends. I get embarrassed if we go to the beach together undressed. So you got to have this sensitivity. (Italian woman, 67—Participant 5) | |

| 3.3 | There’s always embarrassment. I mean, you can never sort of—even women to women, of course, it’s—you’re never at ease. (Italian woman, 57—Participant 2) | |

| 3.4 | I think it’s like just because that embarrassment, like having a pap smear, it’s the same like having breast—I think us, European women, we just think, “Oh, I will go next year,” and you don’t do it. (Croatian woman, 68—Participant 4) | |

| 3.5 | If it’s women doing—I prefer women—female doing it. I don’t like males doing it. I don’t mind seeing the male doctor, but when it’s got to do with just tests like that, I prefer female. (Italian woman, 70—Participant 11) | |

| Language | 3.6 | Yeah the government send the letter to me. And they help me for Italian. You know...for my language (Italian woman, 75—Participant 7) |

| 3.7 | My mother-in-law, she doesn’t speak English at all. Always she needs someone with her, her daughter or her son, anyone. She can’t speak, not even one word. And always she comments and say, “I don’t know this letter, what for.” I said “Mum, when I come to see you, I’ll read it for you.” (Lebanese woman, 53—Participant 1) | |

| 3.8 | Language. You know. I no understand everything. (Italian woman, 75—Participant 7) | |

| 3.9 | Sometimes—you know medical term is a bit harder—questions—so I can’t answer it, but if it is simple, I can answer it. (Fijian woman, 70—Participant 9) | |

| No symptoms | 3.10 | There’s actually no history of breast cancer in my family and I haven’t had no indication that there’s anything going wrong and everything seems to be pretty normal. (Italian woman, 56—Participant 15) |

| Lack of awareness | 3.11 | I don’t think many of my friends—they’re all 50, but I don’t think they have been to those services yet….they’re not really—their awareness is low. (Pakistani woman, 53—Participant 16) |

| 3.12 | Well, I know with the Maltese, they have the biggest morning tea and that’s—they collect money and thing for breast cancer. So that’s really big in our culture. When they’re having things like this, [they should use the opportunity to] make women more aware. (Maltese woman, 61—Participant 14) | |

| Spouse permission | 3.13 | These things I have to talk to my husband first… you know… and then we decide all together… you know.. me and my husband. (Italian woman, 75—Participant 7) |

| Complementary medicine | 3.14 | They’re thinking—some of my friends do not believe in this [screening] and believe they can do natural medicine instead you know. (Italian woman, 75—Participant 10) |

| Emerging Theme | Excerpt Number | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| Other conditions | 4.1 | I don’t wanna go. In my situation, I can’t do it. If they bruise, I’m not allowed to get the bruise. I get the bleeding and then I get sick. I don’t wanna do that. (Lebanese woman, 53—Participant 1) |

| Previous results | 4.2 | On that screening, they actually find that I did have something on the beginning of the breast. But they said, “Oh, there’s nothing to worry about ‘till maybe you’re 70. (Croatian woman, 68—Participant 4) |

| Self-examination | 4.3 | But I wouldn’t want to go, really, to screen. I already check every night, every day when I have my shower, every day. (Italian woman, 75—Participant 10) |

| 4.4 | Like I said before, my fingers can feel it now. If there’s something there, I would run to you [doctors]. I would rather do it that way. (Italian woman, 75—Participant 10) | |

| 4.5 | I think I did try to examine myself to see if there’s anything there. If I find something, I would go but you think, “Oh, yeah, there is nothing there, so I’m all right.” Well, you’re not really expert but you just think, “Oh, it’s okay.”(Croatian woman, 68—Participant 4) | |

| Age | 4.6 | I think up to a certain age, they do. Once you hit the 60 to 65, I’ve—through my experiences, women sort of say, “Look, I’m not gonna worry about it. What for? Everything’s been fine the last ten years. That’s it—I’m getting old. I am old. I’m not gonna bother. (Italian woman 57—Participant 2) |

| Fatalistic beliefs | 4.7 | I think sometimes it’s the fear, finding out. Yeah. They think it’s better if they don’t know. (Italian woman, 70—Participant 11) |

| 4.8 | And some time—actually, they are scared to go there. They don’t want to know anything. Even if they—they don’t want to know. Maybe that’s why—the reason not going. (Pakistani woman, 53—Participant 16) | |

| 4.9 | But if you talk to some people, that’s another thing with my friends, they say, “Oh, if it’s gonna happen, it will happen anyway”. (Italian woman, 67—Participant 5) | |

| Structural barriers | 4.10 | For me, it was the transport. My husband was working and it’s not that close to you to go. (Croatian woman, 68—Participant 4) |

| 4.11 | The traffic and it’s so busy, so different—yeah, I didn’t like going there. (Italian woman, 67—Participant 5) | |

| 4.12 | Yeah, because I think you have to bother people. The people work and they’ve got a family. (Italian woman, 75—Participant 10) | |

| 4.13 | Otherwise, people are so busy today they’re not gonna think for themselves as much, are they? Do you know what I mean? Especially mothers, grandmothers—(Maltese woman, 72—Participant 12) | |

| 4.14 | Because they busy with their children, or they work, and they don’t give it time for life. (Uruguayan woman, 74—Participant 13) |

| Emerging Theme | Excerpt Number | Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| General practitioner | 5.1 | So if the doctor said, “Look, when is the last time you had your checks? I think it’s time for you to go” and give you a referral, then you go. You don’t have no choice but to go. (Croatian woman, 68—Participant 4) |

| 5.2 | A lot of Middle Eastern women look at a GP as a little bit of a higher figure to anybody else. So, whether a friend would tell them, it will be, “Oh, yeah, I should.” But if a GP does make it an issue, I think they would. (Italian woman, 57—Participant 2) | |

| 5.3 | I think for me it’s easy, more easy, less embarrassing to go to the doctor. And I go to and he reminds me to do everything. (Uruguayan woman, 74—Participant 13) | |

| BreastScreen letters | 5.4 | Ladies get the cancer... breast cancer mostly. So, when I receive a letter, I take my interest in to go and see a—go and do a screening for it. (Fijian woman, 70—Participant 9) |

| 5.5 | Yeah, BreastScreen. That’s it, the pink envelope. They sent me a letter asking me to come and have the free breast mammogram done. So I went there and had it done. And then two years later, they sent me another letter reminding me that it’s due. So I went and I got it done again. (Pakistani woman, 53—Participant 16) | |

| Friends and family | 5.6 | I got my brother who—specialist, not here but back home, and he always says, “Make sure you do all the right thing and check yourself and look after yourself. It’s important.” (Italian woman, 67—Participant 5) |

| 5.7 | Yeah. Well, I’m starting to remind my daughter now ‘cause she’s coming of age now. Yes, I think so, mother-daughter thing. (Italian woman, 70—Participant 11) | |

| 5.8 | Every year, I might have breast cancer. My daughter, she says, “You need to go to the screening” for the breast cancer. (Uruguayan woman, 74—Participant 13) | |

| 5.9 | I grow up with the idea prevention is better than cure. So that’s how I was brought up by my grandparents, my parents, so better to know than not. (Italian woman, 67—Participant 5) | |

| Group attendance | 5.10 | That would be a good idea too like if the ladies go in group, maybe they will support each other. They will think, “Okay, we have some support with us.” (Pakistani woman, 53—Participant 16) |

| Media | 5.11 | I came across one of my friend who had—recently who has—diagnosed with cancer. Since then, I’m more aware of it. In addition to that, on TV, Pink Ribbon and stuff—was a campaign also promote me to also raise my awareness of this. (Pakistani woman, 53—Participant 16) |

| 5.12 | You get to hear a lot about famous people on television, like this one had it that one, and you go, “Oh, I should go.” But in family…women do not talk about it and you just put it behind you. (Croatian woman, 68—Participant 4) | |

| Social media | 5.13 | I think the kids, yes. I think so ‘cause you have to think of them and kids maybe persuade the mother. (Maltese woman, 72—Participant 12) |

| 5.14 | But if you put things on Facebook, everyone’s on it. (Maltese woman, 72—Participant 12) | |

| 5.15 | Social media is already playing some role, but I think they should play more than they’re doing at the moment. (Pakistani woman, 53—Participant 16) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jamal, J.; MacMillan, F.; McBride, K.A. Barriers and Facilitators of Breast Cancer Screening amongst Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Women in South Western Sydney: A Qualitative Explorative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179129

Jamal J, MacMillan F, McBride KA. Barriers and Facilitators of Breast Cancer Screening amongst Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Women in South Western Sydney: A Qualitative Explorative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(17):9129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179129

Chicago/Turabian StyleJamal, Javeria, Freya MacMillan, and Kate A. McBride. 2021. "Barriers and Facilitators of Breast Cancer Screening amongst Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Women in South Western Sydney: A Qualitative Explorative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 17: 9129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179129

APA StyleJamal, J., MacMillan, F., & McBride, K. A. (2021). Barriers and Facilitators of Breast Cancer Screening amongst Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Women in South Western Sydney: A Qualitative Explorative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179129