Deviant Peer Affiliation and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Chinese Adolescents: Depression as a Mediator and Sensation Seeking as a Moderator

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Depression as a Potential Mediator

1.2. Sensation Seeking as a Moderator

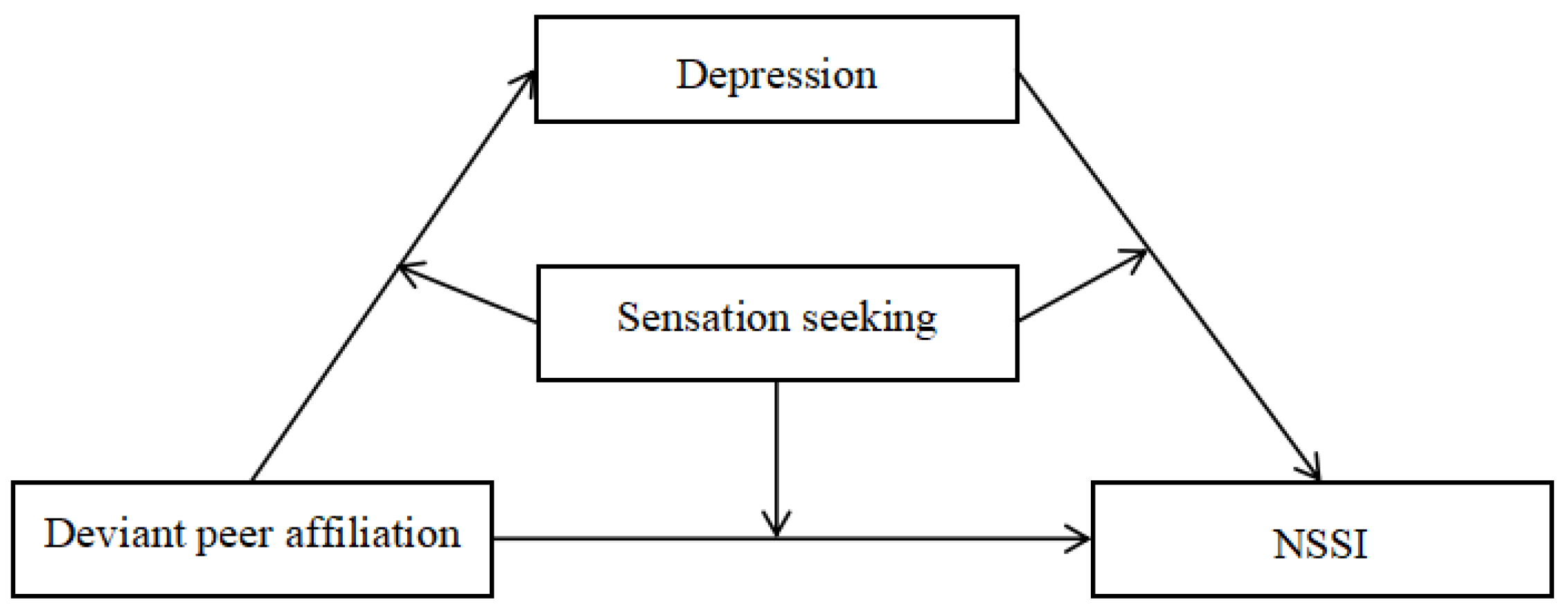

1.3. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Deviant Peer Affiliation

2.2.2. Depression

2.2.3. Sensation Seeking

2.2.4. NSSI

2.2.5. Control Variables

2.3. Procedure and Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

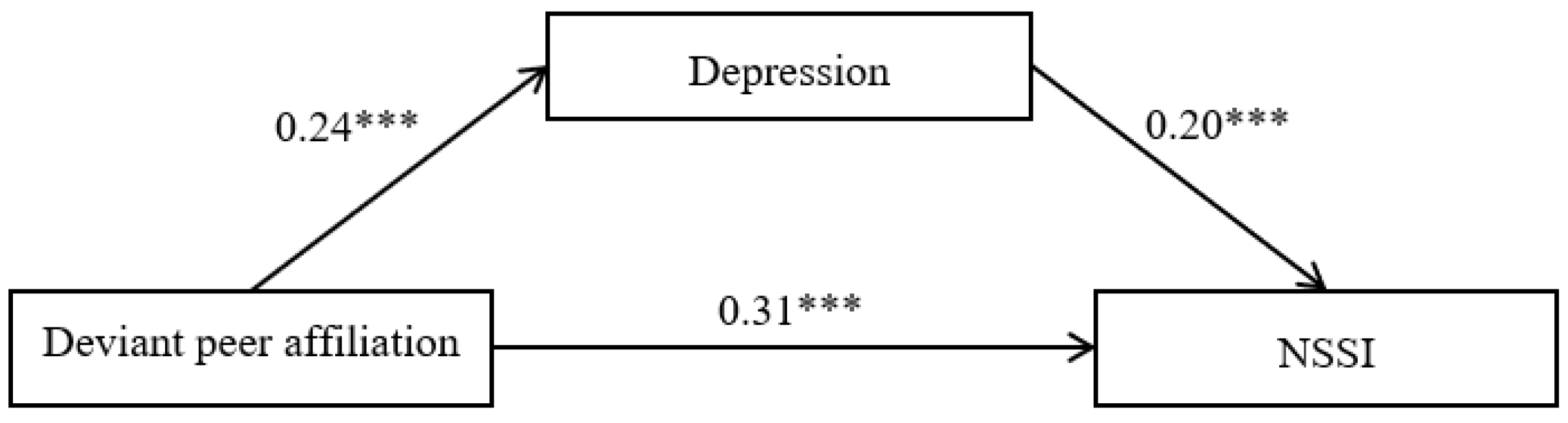

3.2. Mediation Effect of Deviant Peer Affiliation

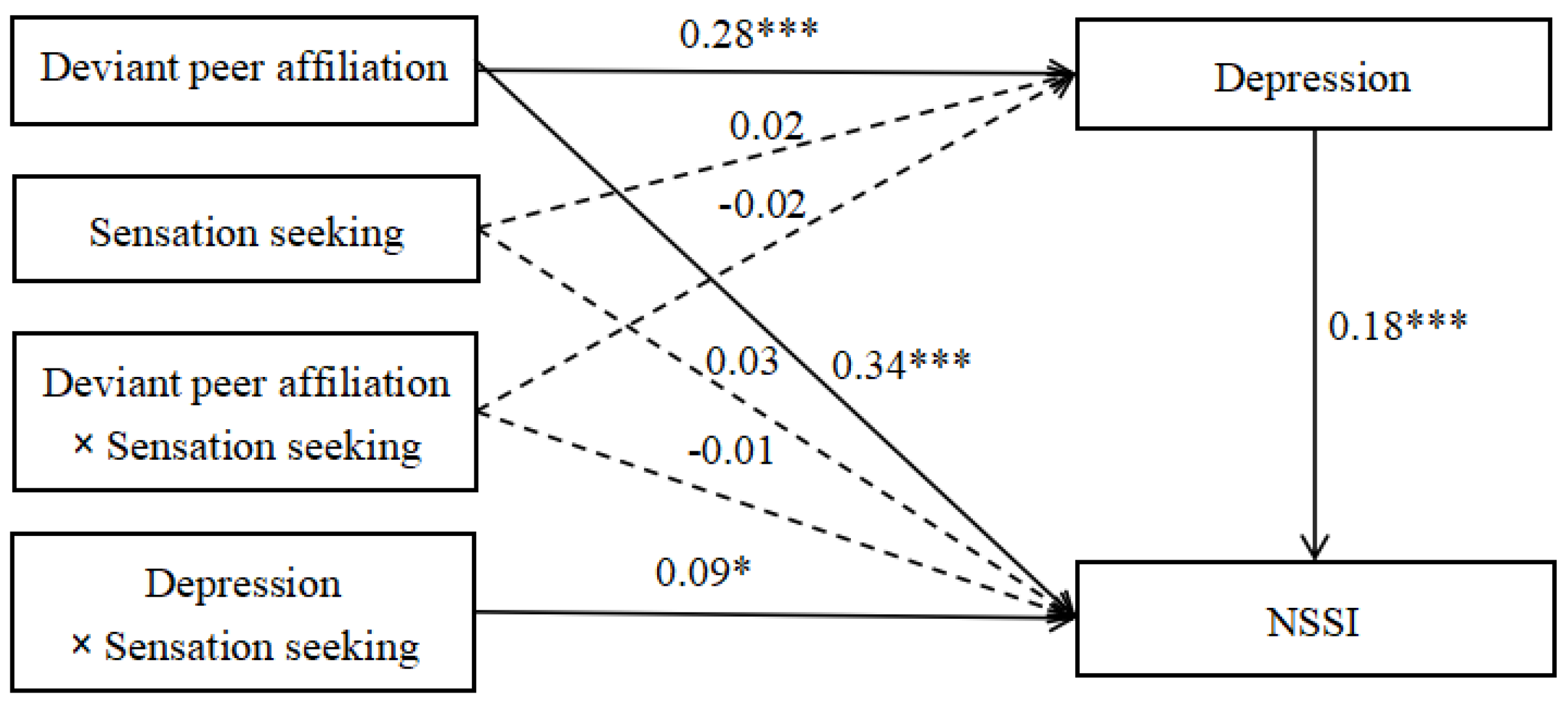

3.3. Moderated Mediation

4. Discussion

4.1. The Mediating Role of Depression

4.2. The Moderating Role of Sensation Seeking

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nock, M.K. Self-injury. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swannell, S.V.; Martin, G.E.; Page, A.; Hasking, P.; St John, N.J. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2014, 44, 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, C.M.; Gould, M. The epidemiology and phenomenology of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents: A critical review of the literature. Arch. Suicide Res. 2007, 11, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.C.; Plener, P.L. Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, R.R.; Lambert, C.E.; La Rochelle, M.; Billet, M.I.; Fekken, G.C. Invalidating childhood environments and nonsuicidal self-injury in university students: Depression and mental pain as potential mediators. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 77, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresin, K.; Mekawi, Y. Different ways to drown out the pain: A meta-analysis of the association between nonsuicidal self-injury and alcohol use. Arch. Suicide Res. 2020, 8, 1802378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, K.-Y.; Hsiao, R.; Yang, Y.-H.; Liu, T.-L.; Yen, C.-F. Predictive effects of sex, age, depression, and problematic behaviors on the incidence and remission of internet addiction in college students: A prospective study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, D. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a predictor of suicidal behavior in depressed adolescents. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, K.; Fox, K.R.; Prinstein, M.J. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a time-invariant predictor of adolescent suicide ideation and attempts in a diverse community sample. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 80, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, E.; Sayal, K.; Townsend, E. Functional coping dynamics and experiential avoidance in a community sample with no self-injury vs. non-suicidal self-injury only vs. those with both non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claes, L.; Houben, A.; Vandereycken, W.; Bijttebier, P.; Muehlenkamp, J. Brief report: The association between non-suicidal self-injury, self-concept and acquaintance with self-injurious peers in a sample of adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2010, 33, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yu, C.; Chen, J.; Sheng, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhong, L. The association between parental psychological control, deviant peer affiliation, and internet gaming disorder among Chinese adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Yu, C.; Lin, S.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W. Sensation seeking, deviant peer affiliation, and internet gaming addiction among Chinese adolescents: The moderating effect of parental knowledge. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J. Prospective childhood predictors of deviant peer affiliations in adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1999, 40, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Wanner, B.; Vitaro, F.; Horwood, L.J.; Swain-Campbell, N. Deviant peer affiliations and depression: Confounding or causation? J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2003, 31, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinstein, M.J.; Heilbron, N.; Guerry, J.D.; Franklin, J.C.; Rancourt, D.; Simon, V.; Spirito, A. Peer influence and nonsuicidal self injury: Longitudinal results in community and clinically-referred adolescent samples. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, S.; Kingsbury, M.; Bennett, K.; Manion, I.; Colman, I. Adolescents’ knowledge of a peer’s non-suicidal self-injury and own non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 142, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K. Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Curr. Dir. Psychol. 2009, 18, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.D.; Weis, J.G. The social development model: An integrated approach to delinquency prevention. J. Prim. Prev. 1985, 6, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotlib, I.H.; Hammen, C.L. (Eds.) Handbook of Depression, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Guerry, J.D.; Prinstein, M.J. Longitudinal prediction of adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: Examination of a cognitive vulnerability-stress model. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Hou, Y.; Chen, P.; You, J. Peer acceptance and nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal moderated mediation model. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1806–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.C.; Li, Q. Adolescent delinquency in child welfare system: A multiple disadvantage model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 73, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G. Childhood emotional abuse and depression among adolescents: Roles of deviant peer affiliation and gender. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; Zhao, F. Paternal parenting and depressive symptoms among adolescents: A moderated mediation model of deviant peer affiliation and school climate. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Prinstein, M.J. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 72, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, C.R.; Klonsky, E.D. A multimethod analysis of impulsivity in nonsuicidal self-injury. Personal. Disord. 2010, 1, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, A.C.; Jenkins, A.L.; Conner, B.T. The role of sensation seeking in non-suicidal self-injury. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2013, 37, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, M.; Bone, R.N.; Neary, R.; Mangelsdorff, D.; Brustman, B. What is the sensation seeker? Personality trait and experience correlates of the Sensation-Seeking Scales. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1972, 39, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, F.D.; Kretsch, N.; Tackett, J.L.; Harden, K.P.; Tucker-Drob, E.M. Person×environment interactions on adolescent delinquency: Sensation seeking, peer deviance and parental monitoring. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 76, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B.; Li, D.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y. Sensation seeking and tobacco and alcohol use among adolescents: A mediated moderation model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2011, 27, 417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Xie, Q.; Lin, S.; Liang, Y.; Wang, G.; Nie, Y.; Wang, J.; Longobardi, C. Cyberbullying victimization and non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among Chinese adolescents: School engagement as a mediator and sensation seeking as a moderator. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 572521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Yang, Q.; Hu, Z. The effect mechanism of parental control, deviant peers and sensation seeking on drug use among reform school students. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2012, 28, 641–650. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. Interaction Effects of Individual Traits and Environmental Factors on Internalization Problems. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Karyadi, K.; Coskunpinar, A.; Dir, A.L.; Cyders, M.A. The interactive effects of affect lability, negative urgency, and sensation seeking on young adult problematic drinking. J. Addict. 2013, 2013, 636854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Yu, C.; Xu, Q.; Wei, C.; Lin, Z. The relationship between peer victimization and pathological Internet games use among junior high school students: A moderated mediation model. Educ. Meas. Eval. 2014, 10, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Su, P.; Zhang, W.; Yu, C.; Liu, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhen, S. Influence of parental marital conflict on adolescent aggressive behavior via deviant peer affiliation: A moderated mediation model. J. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 40, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Ma, L. (Eds.) Handbook of Mental Health Assessment Scales; Chinese Journal of Mental Health Press: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Gao, T.; Ren, H.; Hu, Y.; Qin, Z.; Liang, L.; Mei, S. The relationship between bullying victimization and depression in adolescents: Multiple mediating effects of internet addiction and sleep quality. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 26, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L.; Albert, D.; Cauffman, E.; Banich, M.; Graham, S.; Woolard, J. Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1764–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerman, M.; Eysenck, S.B.; Eysenck, H.J. Sensation seeking in England and America: Cross-cultural, age, and sex comparisons. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1978, 46, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zhen, S.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W. Sensation seeking and online gaming addiction in adolescents: A moderated mediation model of positive affective associations and impulsivity. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Zhen, S.; Wang, Y. Stressful life events and problematic Internet use by adolescent females and males: A mediated moderation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Lin, M.P.; Fu, K.; Leung, F. The best friend and friendship group influence on adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013, 41, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sornberger, M.J.; Heath, N.L.; Toste, J.R.; McLouth, R. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Gender: Patterns of Prevalence, Methods, and Locations among Adolescents. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2012, 42, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Xhunga, N.; Brausch, A.M. Self-injury age of onset: A risk factor for NSSI severity and suicidal behavior. Arch. Suicide Res. 2018, 23, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, A.M.; Dishion, T.J. The contribution of peers to monthly variation in adolescent depressed mood: A short-term longitudinal study with time-varying predictors. Dev. Psychopathol. 2006, 18, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zuckerman, M. Behavioral Expressions and Biosocial Bases of Sensation Seeking; Cambridge Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, M.; Kuhlman, D.M. Personality and risk-taking: Common biosocial factors. J. Personal. 2000, 68, 999–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentopp, S.D.; Conner, B.T.; Fetterling, T.J.; Delgadillo, A.A.; Rebecca, R.A. Sensation seeking and nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescent psychiatric patients. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Ahemaitijiang, N.; Peng, W.; Zhai, B.; Wang, Y. Perceived school climate and delinquency among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation analysis of moral disengagement and effortful control. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, R.K.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Hemphill, S.A.; Catalano, R.F. Peer Group Patterns of Alcohol-Using Behaviors Among Early Adolescents in Victoria, Australia, and Washington State, United States. J. Res. Adolesc. 2015, 26, 902–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wei, C.; Lu, H.; Lai, W.; Xing, J.; Yu, C.; Zhen, S.; Zhang, W. Peer victimization and adolescent depression: The mediating effect of social withdrawal and the moderating effect of teacher-student relationship. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2021, 37, 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H.; Ma, P.; Xia, T. Childhood emotional abuse and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: The mediating role of identity confusion and moderating role of rumination. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 106, 104474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.00 | |||||

| 2. Age | 0.07 * | 1.00 | ||||

| 3. DPA | 0.19 *** | 0.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 4. SS | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.16 *** | 1.00 | ||

| 5. Depression | −0.10 ** | −0.06 | 0.22 *** | 0.06 | 1.00 | |

| 6. NSSI | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.35 *** | 0.10 ** | 0.29 *** | 1.00 |

| Mean | 0.31 | 16.35 | 1.33 | 3.11 | 1.81 | 1.10 |

| SD | 0.47 | 1.15 | 0.45 | 0.97 | 0.36 | 0.27 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, C.; Li, J.; Yu, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhen, S.; Zhang, W. Deviant Peer Affiliation and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Chinese Adolescents: Depression as a Mediator and Sensation Seeking as a Moderator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168355

Wei C, Li J, Yu C, Chen Y, Zhen S, Zhang W. Deviant Peer Affiliation and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Chinese Adolescents: Depression as a Mediator and Sensation Seeking as a Moderator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168355

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Chang, Jingjing Li, Chengfu Yu, Yanhan Chen, Shuangju Zhen, and Wei Zhang. 2021. "Deviant Peer Affiliation and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Chinese Adolescents: Depression as a Mediator and Sensation Seeking as a Moderator" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168355

APA StyleWei, C., Li, J., Yu, C., Chen, Y., Zhen, S., & Zhang, W. (2021). Deviant Peer Affiliation and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Chinese Adolescents: Depression as a Mediator and Sensation Seeking as a Moderator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168355