Acceptability of a Mobile-Health Living Kidney Donor Advocacy Program for Black Wait-Listed Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

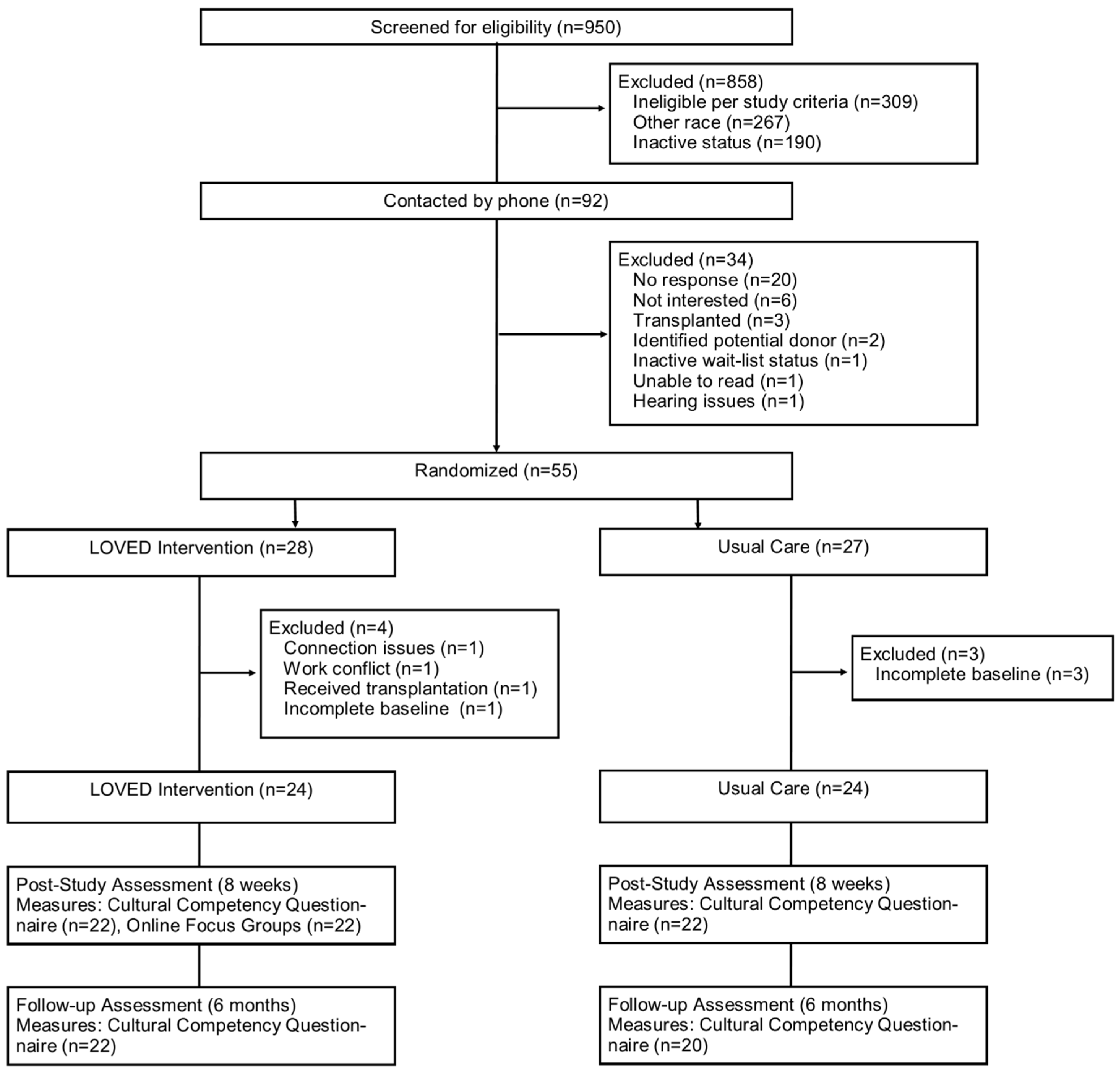

2.1. Study Design

2.2. LOVED Intervention

2.3. Participants

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Protocol

2.6. Measures

2.7. Data Analyses

2.7.1. Quantitative Analyses

2.7.2. Qualitative Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Variables

3.2. Summary of Primary and Secondary Findings

3.3. Thematic Findings

3.3.1. Theme: Video Chat Sessions Provided Essential Support and Encouragement

3.3.2. Theme: Videos Motivated and Made Participants More Knowledgeable

3.3.3. Theme: Connectivity with Tablets Was Acceptable in Most Areas

3.3.4. Theme: Material Was Culturally Sensitive

3.3.5. Theme: Participation Was Overall a Positive Experience

3.3.6. Theme: More Willing to Ask for a Kidney Now

3.4. Participant Perspectives on the LOVED Navigators

“He kept it interesting. He always um bring some good to the table or give us like homework that we can have something to discuss when we come back together.”

“He kept us engaged, and he didn’t just allow you to sit back and not participate. Um he drew you in even when you didn’t want to answer, you had to say something.”

“The format was good because he uh, he been through the process I’m going through so any advice that he gave helped me cross that bridge in my process so…the way it was laid out, the way he gave it was good.”

3.5. Quantitative Findings with Qualitative Integration

“The staff have always been nice and helpful to me when I ask questions.”

“Everyone does a great job; everybody is patient and understanding with any question you have. Thank you for the program and [I] learned a lot.”

“My experience with [the facility’s] Transplant Team has been wonderful. However, there was a few times where there was miscommunication.”

The LOVED group specific questionnaire on trust demonstrated high mean scores for both 8-weeks (mean = 3.95 out of 4 [95% CI: 3.85, 4.05]) and at 6 months. Focus group comments also showed high levels of trust when speaking about their navigators, research staff, and medical staff.

“I have had two prior kidney transplants within a twelve-year period. The doctors and surgeons at [the facility] are very knowledgeable in their field. They perform hundreds of transplants per year. I trust them completely with my life.”

“He’s [speaking about their navigator] had that experience and he told us about stuff that he experienced. Which was great, because to hear somebody else talk about it, without them turning up their nose at you and saying, “oh, you have this”, and they don’t want to hear what you have or whatever, he wasn’t even like that. Not at all. He was great.”

“Me personally? I don’t have a problem with it [meaning discrimination]. But by the way things are looking, this is a disease that affects African Americans a lot, I mean because that basically who’s in this group.”

“For me it was helpful because I was blind to the fact. I thought because I’m a black man, that only a black person could donate a kidney to me, and I found out that’s not true.”

“The format was good because he been through the process I’m going through so any advice that he gave helped me cross that bridge in my process so…the way it was laid out, the way he gave it was good.”

“And I really learned that from him. Because I’m just like, “I’m tired, I’m ready to move forward in my life, I’m just tired of waiting.” So, you know, I learned that from him. That is the most valuable thing that I can get from the program.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Themes

4.2. Comparisons to Other Studies

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Considerations

4.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- System USRD. 2020 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda: Rockville, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Data Reports: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/ (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Taber, D.J.; Gebregziabher, M.; Srinivas, T.; Egede, L.E.; Baliga, P.K. Transplant Center Variability in Disparities for African-American Kidney Transplant Recipients. Ann. Transplant. 2018, 23, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, K.J.; Cmunt, K. Early Experience with New Kidney Allocation System: A Perspective from the Organ Procurement Agency. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 2057–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Robinson, D.H.; Arriola, K.R. Strategies to facilitate organ donation among African Americans. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverdes, J.C.; Nemeth, L.S.; Magwood, G.S.; Baliga, P.K.; Chavin, K.D.; Brunner-Jackson, B.; Treiber, F.A. Patient-Centered mHealth Living Donor Transplant Education Program for African Americans: Development and Analysis. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2015, 4, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Yuen, E.K.; Goetter, E.M.; Herbert, J.D.; Forman, E.M.; Acierno, R.; Ruggiero, K.J. mHealth: A mechanism to deliver more accessible, more effective mental health care. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2014, 21, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaris, E.M.; Warrens, A.N.; Smith, G.; Tekkis, P.; Papalois, V.E. Live kidney donation: Attitudes towards donor approach, motives and factors promoting donation. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012, 27, 2517–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sieverdes, J.C.; Nemeth, L.S.; Magwood, G.S.; Baliga, P.K.; Chavin, K.D.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Treiber, F.A. African American kidney transplant patients’ perspectives on challenges in the living donation process. Prog. Transplant. 2015, 25, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Ralph, A.; Chapman, J.R.; Gill, J.S.; Josephson, M.A.; Hanson, C.S.; Craig, J.C. Public attitudes and beliefs about living kidney donation: Focus group study. Transplantation 2014, 97, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.H.; Klammer, S.M.; Perryman, J.P.; Thompson, N.J.; Arriola, K.R. Understanding African American’s religious beliefs and organ donation intentions. J. Relig. Health 2014, 53, 1857–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnell, T.S.; Powe, N.R.; Troll, M.U.; Wang, N.Y.; Haywood, C., Jr.; LaVeist, T.A.; Boulware, L.E. Measuring and explaining racial and ethnic differences in willingness to donate live kidneys in the United States. Clin. Transplant. 2013, 27, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulware, L.E.; Hill-Briggs, F.; Kraus, E.S.; Melancon, J.K.; Senga, M.; Evans, K.E.; Powe, N.R. Identifying and addressing barriers to African American and non-African American families’ discussions about preemptive living related kidney transplantation. Prog. Transplant. 2011, 21, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, E.A.; Ruck, J.M.; Garonzik-Wang, J.; Bowring, M.G.; Kumar, K.; Purnell, T.; Segev, D.L. Addressing Racial Disparities in Live Donor Kidney Transplantation through Education and Advocacy Training. Transplant. Direct 2020, 6, e593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaPointe Rudow, D.; Geatrakas, S.; Armenti, J.; Tomback, A.; Khaim, R.; Porcello, L.; Shapiro, R. Increasing living donation by implementing the Kidney Coach Program. Clin. Transplant. 2019, 33, e13471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobile Fact Sheet: Pew Research Center. 2019. Updated 12 June 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Sieverdes, J.C.; Price, M.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Baliga, P.K.; Chavin, K.D.; Brunner-Jackson, B.; Treiber, F.A. Design and approach of the Living Organ Video Educated Donors (LOVED) program to promote living kidney donation in African Americans. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2017, 61, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieverdes, J.C.; Treiber, F.A.; Mueller, M.; Nemeth, L.S.; Brunner-Jackson, B.; Anderson, A.; Baliga, P.K. Living Organ Video Educated Donors Program for Kidney Transplant-eligible African Americans to Approach Potential Donors: A Proof of Concept. Transplant. Direct 2018, 4, e357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverdes, J.C.; Mueller, M.; Nemeth, L.S.; Patel, S.; Baliga, P.K.; Treiber, F.A. A distance-based living donor kidney education program for Black wait-list candidates: A feasibility randomized trial. Clin. Transplant. 2021, e14426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, J.R.; Green, A.R.; Carrillo, J.E. New York: The Commonwealth Fund. 2002. Updated 1 October 2002. Available online: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2002/Oct/Cultural-Competence-in-Health-Care--Emerging-Frameworks-and-Practical-Approaches.aspx (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Your Health and Health Opinions, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): Department of Health & Human Performance. 2010. Available online: https://meps.ahrq.gov/survey_comp/hc_survey/paper_quest/2010/2010_SAQ_ENG.shtml (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Dugan, E.; Trachtenberg, F.; Hall, M.A. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2005, 5, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N.; Smith, K.; Naishadham, D.; Hartman, C.; Barbeau, E.M. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1576–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriston, L.; Scholl, I.; Holzel, L.; Simon, D.; Loh, A.; Harter, M. The 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 80, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, A. How to Design Survey Studies. The Survey Kid, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage Publications: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Dickinson, W.B.; Leech, N.L.; Zoran, A.G. A Qualitative Framework for Collecting and Analyzing Data in Focus Group Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkan, J. Immersion/Crystallization; Crabtree, B.F., Miller, W.L., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A.D.; McSorley, A.M.; Peipert, J.D.; Goalby, C.J.; Peace, L.J.; Lutz, P.A.; Thein, J.L. Explore Transplant at Home: A randomized control trial of an educational intervention to increase transplant knowledge for Black and White socioeconomically disadvantaged dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2015, 16, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strigo, T.S.; Ephraim, P.L.; Pounds, I.; Hill-Briggs, F.; Darrell, L.; Ellis, M.; Sudan, D.; Rabb, H.; Segev, D.; Wang, N.-Y. The TALKS study to improve communication, logistical, and financial barriers to live donor kidney transplantation in African Americans: Protocol of a randomized clinical trial. BMC Nephrol. 2015, 16, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Overall program administration:

|

| Characteristics | LOVED (n = 24) | Usual Care (n = 24) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y [mean (SD)] | 50.9 (9.2) | 47.9 (10.0) | 0.29 |

| Sex (Male), [n, %] | 12, 50.0% | 12, 50.0% | >0.99 |

| Marital status, [n, %] Lives alone Married or living with significant other | 9, 37.5% 15, 62.5% | 13, 54.2% 11, 45.8% | 0.31 |

| Educational attainment, [n, %] Less than high school High school diploma or GED College or Technical School | 4, 16.7% 5, 20.8% 15, 62.5% | 1, 4.3% 7, 30.4% 15, 65.2% | 0.85 a |

| Employment status, [n, %] Working part or full time Retired Disabled or unemployed | 8, 33.3% 1, 4.2% 15, 62.5% | 4, 17.4% 2, 8.7% 17, 73.9% | 0.37 b |

| Themes | Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Scale | LOVED Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Usual Care Mean (SD) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication at 8 weeks | 3.93 (0.15) | 3.86, 3.99 | 3.78 (0.33) | 3.62, 3.93 | 0.07 * |

| Communication at 6 months | 3.85 (0.31) | 3.71, 3.99 | 3.82 (0.28) | 3.68, 3.95 | 0.71 |

| Trust at 8 weeks | 3.95 (0.22) | 3.85, 4.05 | - | - | - |

| Trust at 6 months | 3.85 (0.31) | 3.70, 4.00 | - | - | - |

| Discrimination at 8 weeks | 3.96 (0.13) | 3.89, 4.02 | 3.86 (0.36) | 3.71, 4.02 | 0.27 * |

| Discrimination at 6 months | 3.96 (0.15) | 3.89, 4.02 | 3.78 (0.72) | 3.42, 4.14 | 0.32 * |

| Decision Making at 8 weeks | 1.33 (0.67) | 1.01, 1.64 | - | - | - |

| Decision Making at 6 months | 1.63 (1.03) | 1.16, 2.12 | - | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sieverdes, J.C.; Nemeth, L.S.; Mueller, M.; Rohan, V.; Baliga, P.K.; Treiber, F. Acceptability of a Mobile-Health Living Kidney Donor Advocacy Program for Black Wait-Listed Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168239

Sieverdes JC, Nemeth LS, Mueller M, Rohan V, Baliga PK, Treiber F. Acceptability of a Mobile-Health Living Kidney Donor Advocacy Program for Black Wait-Listed Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168239

Chicago/Turabian StyleSieverdes, John C., Lynne S. Nemeth, Martina Mueller, Vivik Rohan, Prabhakar K. Baliga, and Frank Treiber. 2021. "Acceptability of a Mobile-Health Living Kidney Donor Advocacy Program for Black Wait-Listed Patients" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168239

APA StyleSieverdes, J. C., Nemeth, L. S., Mueller, M., Rohan, V., Baliga, P. K., & Treiber, F. (2021). Acceptability of a Mobile-Health Living Kidney Donor Advocacy Program for Black Wait-Listed Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168239