Subjective Well-Being and Parenthood in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Variables and Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duarte-Duarte, J. Contemporary childhoods, media and authority. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez Juv. 2013, 11, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBlain, S.; Dunn, J.; Luke, I. Contemporary Childhood; Sage: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–256. [Google Scholar]

- Paris School of Economics. Available online: http://www.parisschoolofeconomics.com/clark-andrew/HappinessandtheParenthoodParadox.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- McLanahan, S.; Adams, J. The effects of children on adults’ psychological well-being: 1957–1976. Soc. Forces 1989, 68, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandel, M.; Melchiorri, E.; Ruini, C. The Dynamics of Eudaimonic Well-Being in the Transition to Parenthood: Differences Between Fathers and Mothers. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 2572–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.M.; A Wallace, S.; Doehler, K.; Dantzler, J. Parentification, Ethnic Identity, and Psychological Health in Black and White American College Students: Implications of Family-of-Origin and Cultural Factors. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2012, 43, 811–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.M.; Tomek, S.; Bond, J.M.; Reif, M.S. Race/Ethnicity, Gender, Parentification, and Psychological Functioning. Fam. J. 2015, 23, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, P.; Vergara, A. Ser Niño y Niña en el Chile de Hoy: La Perspectiva de sus Protagonistas Acerca de la Infancia, la Adultez y Las Relaciones Entre Padres e Hijos; Ceibo: Santiago, Chile, 2017; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, T.R.; Guimarães, L.E.; Silva, M.D.R.; Lopes, R.D.C.S.; Piccinini, C.A. Experiência da paternidade aos três meses do bebê. Psicol. Reflexão Crítica 2013, 26, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bustamante, V. Participação paterna no cuidado durante o primeiro ano de vida. Pensando Famílias 2019, 23, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Palladino, H. The cultural contradictions of fatherhood: Is there an ideology of intensive fathering? In Intensive Mothering: The Cultural Contradictions of Modern Motherhood; Ennis, L., Ed.; Demeter Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014; pp. 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Faircloth, C. Utterly heart-breaking and devastating: Couple relationships and intensive parenting culture in a time of Cold intimacies. In Romantic Relationships in a Time of Cold Intimacies; Carter, J., Arocha, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Yerkes, M.A.; Hopman, M.; Stok, F.M.; De Wit, J. In the best interests of children? The paradox of intensive parenting and children’s health. Crit. Public Heal. 2021, 31, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.K.; Kushlev, K.; Dunn, E.W.; Lyubomirsky, S. Parents Are Slightly Happier Than Nonparents, but Causality Still Cannot Be Inferred. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 25, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson-Coffey, S.K.; Stewart, D. Well-Being in Parenting. In Handbook of Parenting; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 596–619. [Google Scholar]

- Mikucka, M.; Rizzi, E. The Parenthood and Happiness Link: Testing Predictions from Five Theories. Eur. J. Popul. 2020, 36, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, R.J.; Simon, R.W. Clarifying the Relationship Between Parenthood and Depression. J. Heal. Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, J.; Simon, R.W.; Andersson, M.A. Parenthood and Happiness: Effects of Work-Family Reconciliation Policies in 22 OECD Countries. Am. J. Sociol. 2016, 122, 886–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugur, Z.B. Does Having Children Bring Life Satisfaction in Europe? J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 21, 1385–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanca, L. The geography of parenthood and well—being: Do children make us happy, where and why. World Happiness Rep. 2016, 2, 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Loui, A.D.; Cromer, L.D.; Berry, J.O. Assessing parenting stress: Review of the use and interpretation on the parental stress scale. Fam. J. 2017, 25, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomaguchi, K.; Milkie, M.A. Parenthood and well-being: A decade in review. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczak, M.; Gross, J.J.; Roskam, I. Parental burnout: What is it, and why does it matter? Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskam, I.; Aguiar, J.; Akgun, E.; Arikan, G.; Artavia, M.; Avalosse, H.; Aunola, K.; Bader, M.; Bahati, C.; Barham, E.J.; et al. Parental Burnout Around the Globe: A 42-Country Study. Affect. Sci. 2021, 2, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrazas-Carrillo, E.; McWhirter, P.T.; Muetzelfeld, H.K. Happy parents in Latin America? Exploring the impact of gender, work-family satisfaction, and parenthood on general life happiness. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2016, 3, 140–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, G.G. Las mujeres y el análisis de clases en la Argentina: Una aproximación a su abordaje. Lavboratorio 2018, 28, 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, K.; Martuccelli, D. Desafíos Comunes: Retrato de la Sociedad Chilena y Sus Individuos; LOM: Santiago, Chile, 2012; pp. 248–302. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara, A.C.; Sepúlveda, M.A.; Chávez, P.B. Parentalidades intensivas y éticas del cuidado: Discursos de niños y adultos de estrato bajo de Santiago, Chile. Psicoperspectivas 2018, 17, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD). Desarrollo Humano en Chile. Bienestar Subjetivo: El Desafío de Repensar el Desarrollo; Salesianos Impresores S.A.: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2012; pp. 30–306. [Google Scholar]

- Edlund, J. Trabalhos Exigentes? Demandas conflitantes de atividade remunerada e não remunerada entre casais que trabalham em 29 países. In Novas Conciliações e Antigas Tensões? Gênero, Família e Trabalho em Perspectiva Comparada; Edlund, J., Ed.; EDUSC: Bauru, Brasil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bornatici, C.; Heers, M. Work–Family Arrangement and Conflict: Do Individual Gender Role Attitudes and National Gender Culture Matter? Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio Ministerio de Desarrollo Social. Available online: http://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/encuesta-casen-2011 (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Observatorio Ministerio de Desarrollo Social. Available online: http://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/encuesta-casen-2017 (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Domínguez, A.; Amorós, M.; Muñiz Terra, L.M.; Donoso, G.R. El trabajo doméstico y de cuidados en las parejas de doble ingreso. Análisis Comparativo entre España, Argentina y Chile. Papers 2019, 104, 307–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña, I.; Calquín, C.; Silva, S.; García, M. Diversidad Familiar, Relaciones de Género y Producción de Cuidados en Salud en el Modelo de Salud Familiar: Análisis de Caso en un CESFAM de la Región Metropolitana, Chile. Ter. Psicológica 2011, 29, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.J.; Urrutia, V.G.; Palomo-Vélez, G. Work-Family Balance, Participation in Family Work and Parental Self-Efficacy in Chilean Workers. Can. J. Fam. Youth 2017, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio Ministerio de Desarrollo Social. Available online: http://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/encuesta-casen-2009 (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Valdés, X. El lugar que habita el padre en Chile contemporáneo. Estudio de las representaciones sobre la paternidad en distintos grupos sociales. Polis 2009, 8, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña-Muñoz, L. Relaciones de género y arreglos domésticos: Masculinidades cambiantes en Concepción, Chile. Polis Rev. Latinoam. 2018, 30, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollmann-Schult, M. Single motherhood and life satisfaction in comparative perspective: Do institutional and cultural contexts explain the life satisfaction penalty for single mothers? J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 2061–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olhaberry, M.; Farkas, C. Estrés materno y configuración familiar: Estudio comparativo en familias chilenas monoparentales y nucleares de bajos ingresos. Univ. Psychol. 2012, 11, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Díaz, P.A.; Cádiz, D.O. Burnout parental en Chile y género: Un modelo para comprender el burnout en madres chilenas. Rev. Psicol. 2020, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beytía, P.; Calvo, E. Cómo medir la felicidad. Inst. Políticas Públicas UDP 2011, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013; pp. 27–125. [Google Scholar]

- Cantril, H. The Pattern of Human Concerns; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1965; pp. 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Villarroel, P.; Urzúa, A.; Jaime, D.; Contreras, D.; Zych, I.; Celis-Atenas, K.; Silva, J.R.; Lillo, S. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Psychometric properties and discriminative capacity in several Chilean samples. Eval. Health Prof. 2019, 42, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, O.F.; Fuentes, M.C.; Gracia, E.; Serra, E.; Garcia, F. Parenting Warmth and Strictness across Three Generations: Parenting Styles and Psychosocial Adjustment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H. Handbook of Parenting, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; Volume 4, pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, S.; Kushlev, K.; Lyubomirsky, S. The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well-being? Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 846–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinraub, M.; Kaufman, R. Single Parenthood. In Handbook of Parenting, 3rd ed.; Bornstein, M.H., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 271–310. [Google Scholar]

- Faircloth, C. Intensive parenting and the expansion of parenting. In Parenting Culture Studies; Lee, E., Bristow, J., Faircloth, C., Macvarish, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Musick, K.; Meier, A.; Flood, S. How parents fare: Mothers’ and fathers’ subjective well-being in time with children. Am. Soc. Rev. 2016, 81, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupica, C. Trabajo Decente y Cuidado Compartido: Hacia una Propuesta de Parentalidad; Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT)/Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD): Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2013; pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Aguayo, F.; Levtov, R.; Brown, V.; Barker, G.; Barindelli, F. Estado de La Paternidad: América Latina y El Caribe; Promundo-US: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 1–130. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T. Parenthoods: Setting the Contemporary Context. In Making Sense of Parenthood: Caring, Gender and Family Lives; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 8–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson-Coffey, S.K.; Killingsworth, M.; Layous, K.; Cole, S.W.; Lyubomirsky, S. Parenthood is associated with greater well-being for fathers than mothers. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 45, 1378–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, S.; Kassam, K.S.; Loewenstein, G. A reassessment of the defense of parenthood. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothrauff, T.; Cooney, T.M. The role of generativity in psychological well-being: Does it differ for childless adults and parents? J. Adult Dev. 2008, 15, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chee, K.H.; Gerhart, O. Redefining generativity: Through life course and pragmatist lenses. Sociol. Compass 2017, 11, e12533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, C. La Política en el Neoliberalismo. Experiencias Latinoamericanas; LOM Ediciones: Santiago, Chile, 2019; pp. 34–72. [Google Scholar]

- Castilla, M. La construcción de la “buena paternidad” en hombres jóvenes residentes en barrios pobres de Buenos Aires. Rev. Punto Género 2018, 10, 110–132. [Google Scholar]

- Minkov, M.; Dutt, P.; Schachner, M.; Morales, O.; Sanchez, C.; Jandosova, J.; Khassenbekov, Y.; Mudd, B. A revision of Hofstede’s individualism-collectivism dimension. Cross Cult. Strat. Manag. 2017, 24, 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, G.; Marín, B.V. Research with Hispanic Populations; Sage Publications Inc: Newbury, UK, 1991; pp. 1–144. ISBN 9780803937215. [Google Scholar]

| Men with and without Children | Women with and without Children | Men and Women with and without Children | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With (Media) | SD | Without (Media) | SD | With and Without (Media) | SD | p | With (Media) | SD | Without (Media) | SD | With and Without (Media) | SD | p | With (Media) | SD | Without (Media) | SD | With and Without (Media) | SD | p | |

| 1. Life satisfaction | 7.21 | 2.11 | 7.41 | 1.96 | 7.27 | 2.07 | 7.2 | 2.25 | 7.76 | 1.87 | 7.27 | 2.21 | *** | 7.2 | 2.19 | 7.52 | 1.94 | 7.27 | 2.14 | *** | |

| 2. Ladder of the best possible life | 6.9 | 1.97 | 7.1 | 1.99 | 6.96 | 1.97 | 6.87 | 2.11 | 7.48 | 1.89 | 6.95 | 2.09 | *** | 6.88 | 2.05 | 7.22 | 1.97 | 6.95 | 2.04 | *** | |

| 3. Suffering | 5.99 | 2.36 | 5.55 | 2.44 | 5.87 | 2.39 | * | 6.59 | 2.53 | 5.3 | 2.41 | 6.42 | 2.55 | *** | 6.32 | 2.47 | 5.47 | 2.43 | 6.14 | 2.49 | *** |

| 4. Depressive symptomatology | 2.17 | 0.85 | 2.09 | 0.81 | 2.15 | 0.84 | 2.51 | 0.97 | 2.23 | 0.8 | 2.47 | 0.95 | *** | 2.36 | 0.94 | 2.14 | 0.81 | 2.31 | 0.91 | *** | |

| 5. Positive affect | 3.83 | 0.68 | 3.94 | 0.66 | 3.86 | 0.68 | * | 3.73 | 0.77 | 3.9 | 0.64 | 3.75 | 0.75 | *** | 3.77 | 0.73 | 3.92 | 0.65 | 3.8 | 0.72 | *** |

| 6. Negative affect | 2.72 | 0.75 | 2.69 | 0.74 | 2.71 | 0.74 | 3.02 | 0.8 | 2.79 | 0.66 | 2.99 | 0.79 | *** | 2.89 | 0.79 | 2.72 | 0.71 | 2.85 | 0.78 | *** | |

| 7. Happiness | 3.1 | 0.68 | 3.06 | 0.67 | 3.09 | 0.68 | 2.97 | 0.76 | 3.14 | 0.66 | 2.99 | 0.75 | ** | 3.03 | 0.73 | 3.09 | 0.67 | 3.04 | 0.71 | . | |

| 8. SR a | 8.8 | 1.65 | 8.77 | 1.6 | 8.79 | 1.63 | 8.38 | 2.1 | 8.82 | 1.66 | 8.44 | 2.05 | ** | 8.57 | 1.92 | 8.79 | 1.62 | 8.61 | 1.87 | ||

| 9. Sex life | 7.64 | 2.25 | 7.59 | 2.34 | 7.63 | 2.27 | 6.65 | 2.8 | 7.44 | 2.47 | 6.76 | 2.77 | *** | 7.09 | 2.62 | 7.54 | 2.38 | 7.19 | 2.58 | * | |

| 10. Free time | 2.97 | 0.99 | 2.97 | 0.97 | 2.97 | 0.99 | 2.91 | 1.02 | 3.13 | 0.92 | 2.94 | 1.01 | ** | 2.94 | 1.01 | 3.02 | 0.95 | 2.95 | 1 | * | |

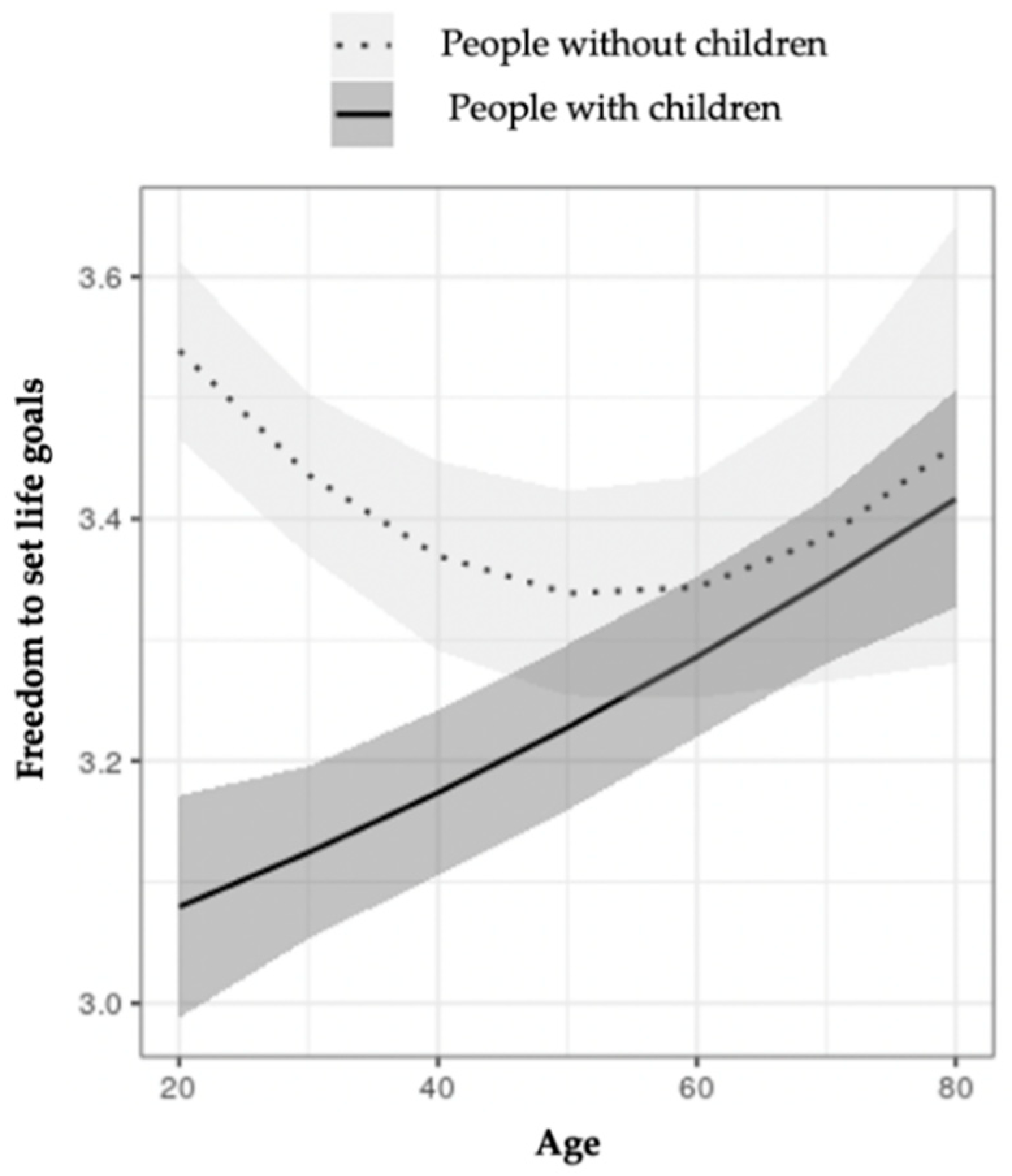

| 11. FSLG b | 3.23 | 0.87 | 3.42 | 0.74 | 3.29 | 0.84 | ** | 3.07 | 0.93 | 3.48 | 0.71 | 3.12 | 0.91 | *** | 3.14 | 0.91 | 3.44 | 0.73 | 3.2 | 0.88 | *** |

| Well-Being Dimensions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Life satisfaction | 1 ** | 0.62 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.36 ** | 0.35 ** | −0.36 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.22 ** |

| 2. Ladder of the best possible life | 1 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.34 ** | 0.35 ** | −0.32 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.23 ** | |

| 3. Suffering | 1 ** | 0.27 ** | −0.11 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.00 | −0.09 ** | ||

| 4. Depressive Symptomatology | 1 ** | −0.44 ** | 0.55 ** | −0.39 ** | −0.26 ** | −0.26 ** | −0.09 ** | −0.26 ** | |||

| 5. Positive affect | 1 ** | −0.42 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.28 ** | ||||

| 6. Negative affect | 1 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.22 ** | |||||

| 7. Happiness | 1 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.26 ** | ||||||

| 8. Satisfaction with relationship | 1 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.18 ** | |||||||

| 9. Sex life | 1.00 ** | 0.05 | 0.20 ** | ||||||||

| 10. Free time | 1.00 ** | 0.16 ** | |||||||||

| 11. Freedom to set life goals | 1.00 ** |

| Well-Being Dimensions | Without Children | With Children | d | Test of the Difference between People with and without Children a | Interaction between Having and Not Having Children with Socioeconomic Status and Age b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Life satisfaction (LS) | 7.7 | 7.47 | 0.11 | F (1.000, 70634.595) = 2.518, p = 0.113 | F (7.000, 880577.800) = 1.021, p = 0.414 |

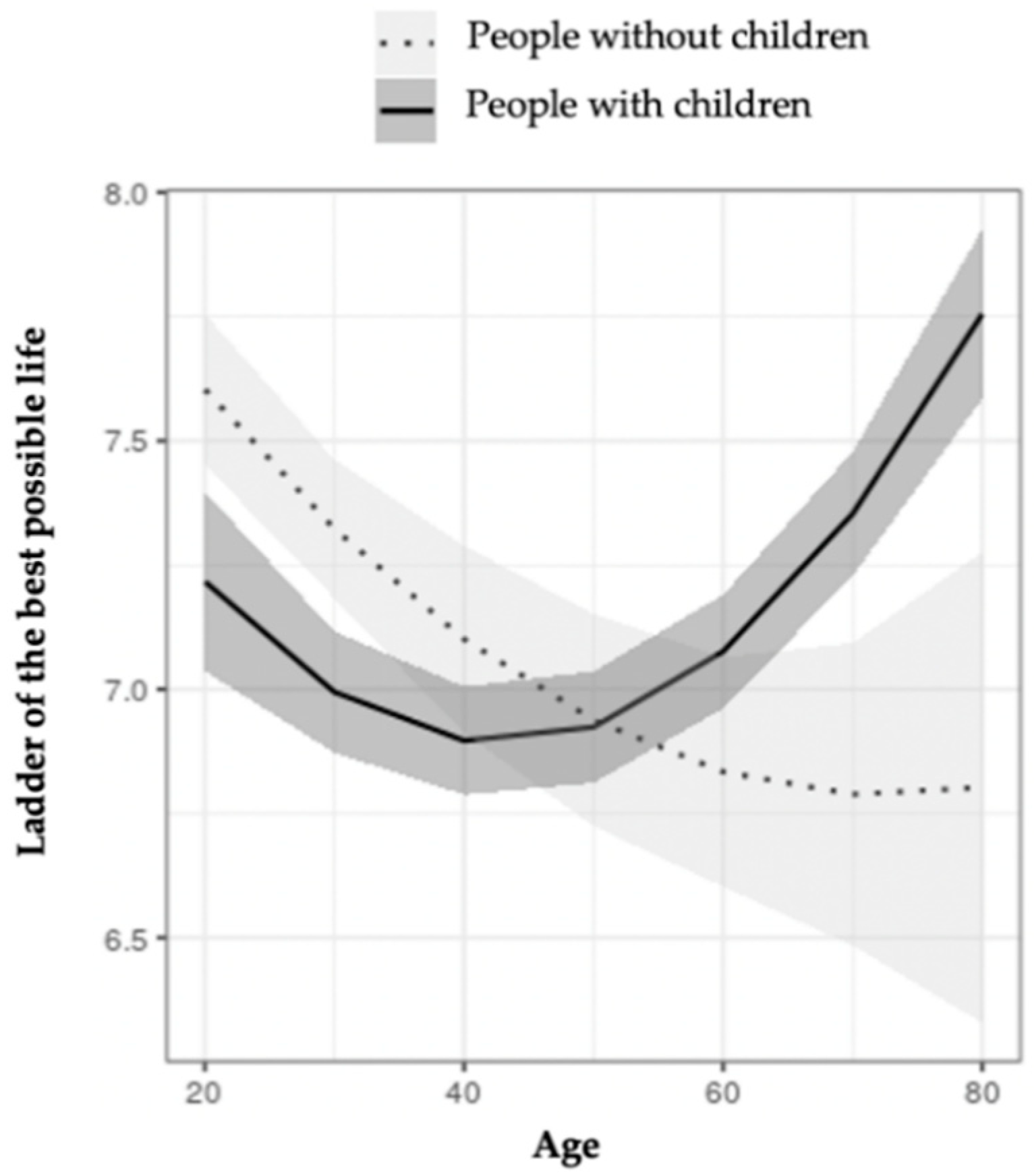

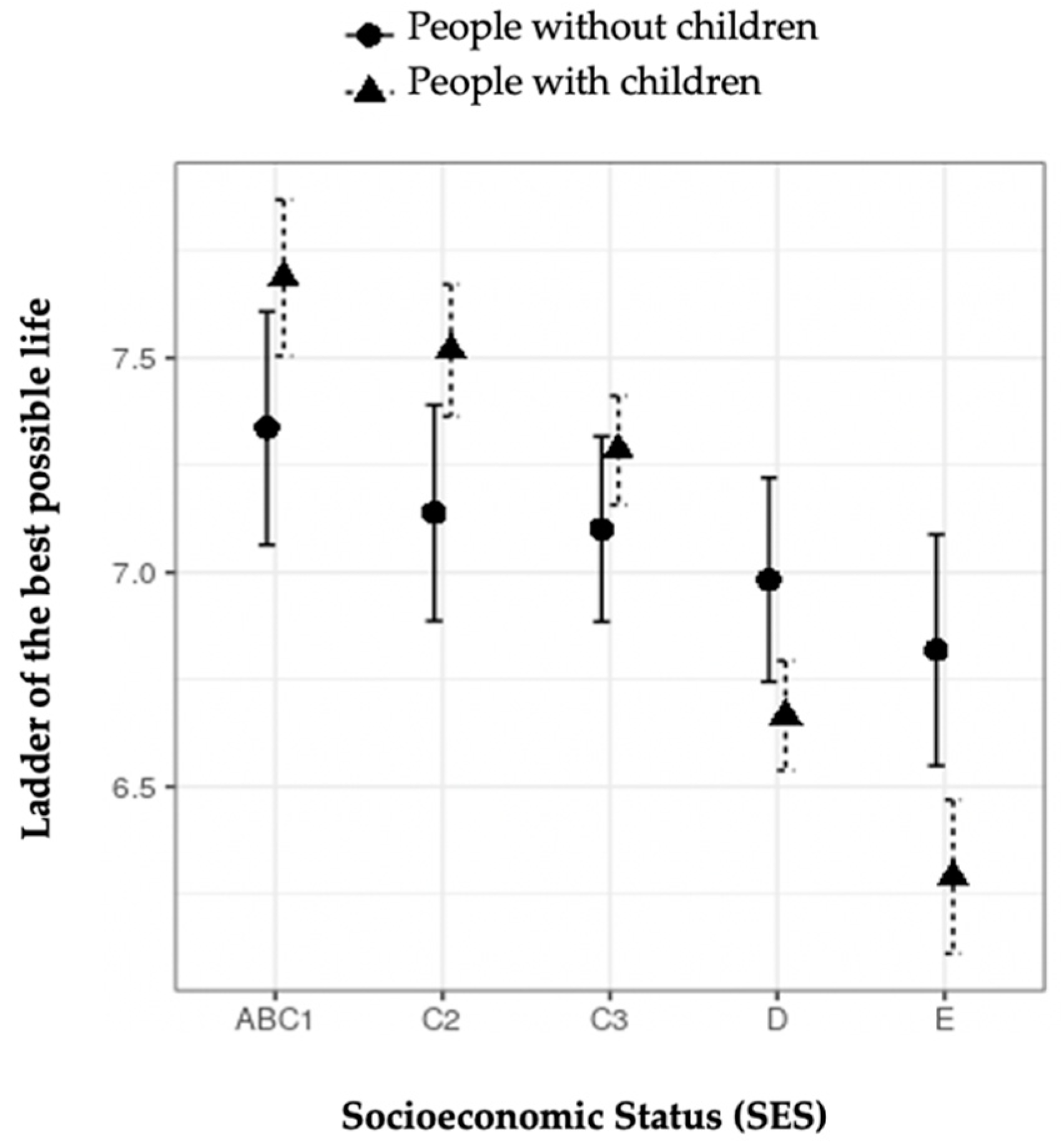

| 2. Ladder of the best possible life | 7.24 | 7.09 | 0.08 | F (1.000, 25325.281) = 1.104, p = 0.293 | F (7.000, 1101321.113) = 2.278, p = 0.026 |

| 3. Suffering | 5.65 | 5.95 | 0.13 | F (1.000, 27216.497) = 3.820, p = 0.051 | F (7.000, 2120919.148) = 1.775, p = 0.087 |

| 4. Depressive symptomatology (DS) | 2.12 | 2.2 | 0.09 | F (1.000, 26554.745) = 1.871, p = 0.171 | F (7.000, 1719087.595) = 0.857, p = 0.540 |

| 5. Positive affect (PA) | 4.01 | 3.83 | 0.24 | F (1.000, 41284.314) = 15.044, p = 0.000 | F (7.000, 1825570.601) = 1.105, p = 0.357 |

| 6. Negative affect (NA) | 2.56 | 2.74 | 0.24 | F (1.000, 44297.595) = 13.278, p = 0.000 | F (7.000, 3793673.359) = 1.126, p = 0.343 |

| 7. Happiness | 3.07 | 3.09 | 0.02 | F (1.000, 29844.828) = 0.118, p = 0.731 | F (7.000, 830267.892) = 1.609, p = 0.127 |

| 8. Satisfaction with relationship | 8.88 | 8.66 | 0.12 | F (1.000, 15.322) = 1.472, p = 0.243 | F (7.000, 446.394) = 0.655, p = 0.710 |

| 9. Sex life | 7.3 | 7.08 | 0.09 | F (1.000, 861.028) = 1.926, p = 0.166 | F (7.000, 769.221) = 1.349, p = 0.224 |

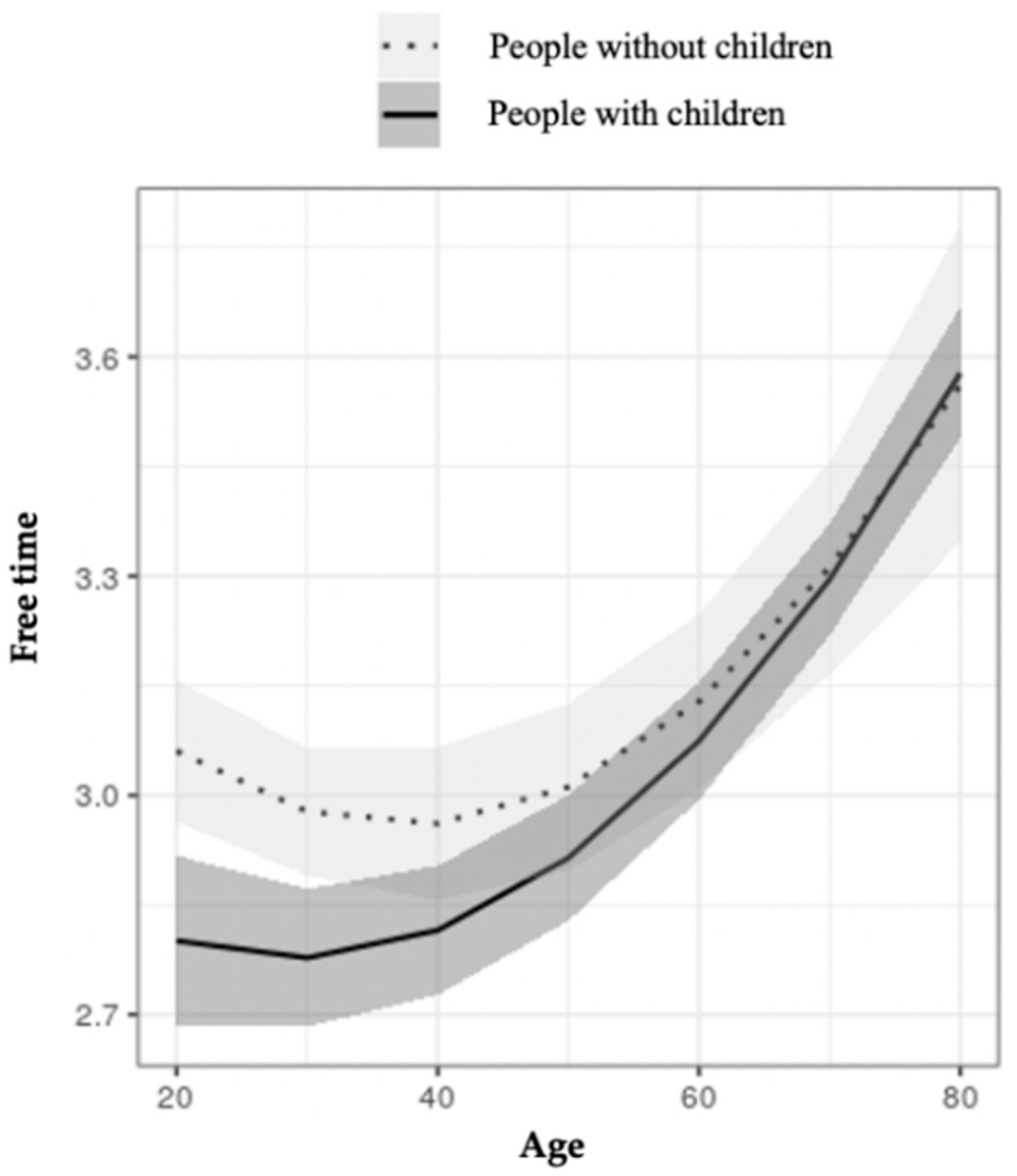

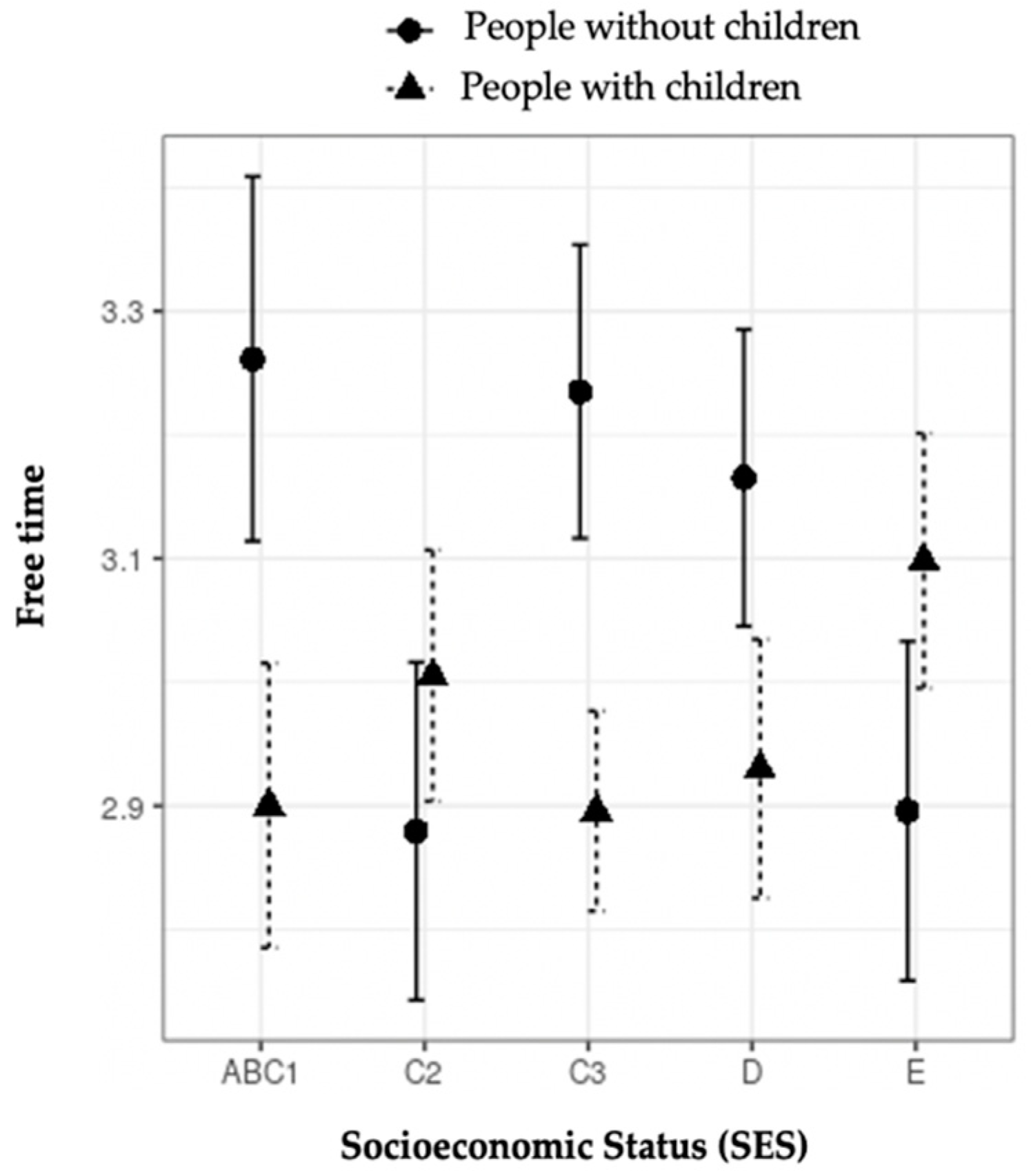

| 10. Free time | 3.14 | 2.97 | 0.18 | F (1.000, 8577.039) = 7.254, p = 0.007 | F (7.000, 910339.668) = 3.564, p = 0.001 |

| 11. Freedom to set life goals | 3.45 | 3.23 | 0.26 | F (1.000, 25616.367) = 15.429, p = 0.000 | F (7.000, 754387.778) = 2.149, p = 0.035 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Novoa, C.; Bustos, C.; Bühring, V.; Oliva, K.; Páez, D.; Vergara-Barra, P.; Cova, F. Subjective Well-Being and Parenthood in Chile. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147408

Novoa C, Bustos C, Bühring V, Oliva K, Páez D, Vergara-Barra P, Cova F. Subjective Well-Being and Parenthood in Chile. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(14):7408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147408

Chicago/Turabian StyleNovoa, Consuelo, Claudio Bustos, Vasily Bühring, Karen Oliva, Darío Páez, Pablo Vergara-Barra, and Félix Cova. 2021. "Subjective Well-Being and Parenthood in Chile" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 14: 7408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147408

APA StyleNovoa, C., Bustos, C., Bühring, V., Oliva, K., Páez, D., Vergara-Barra, P., & Cova, F. (2021). Subjective Well-Being and Parenthood in Chile. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147408