Relational Capital and Post-Traumatic Growth: The Role of Work Meaning

Abstract

:1. Introduction

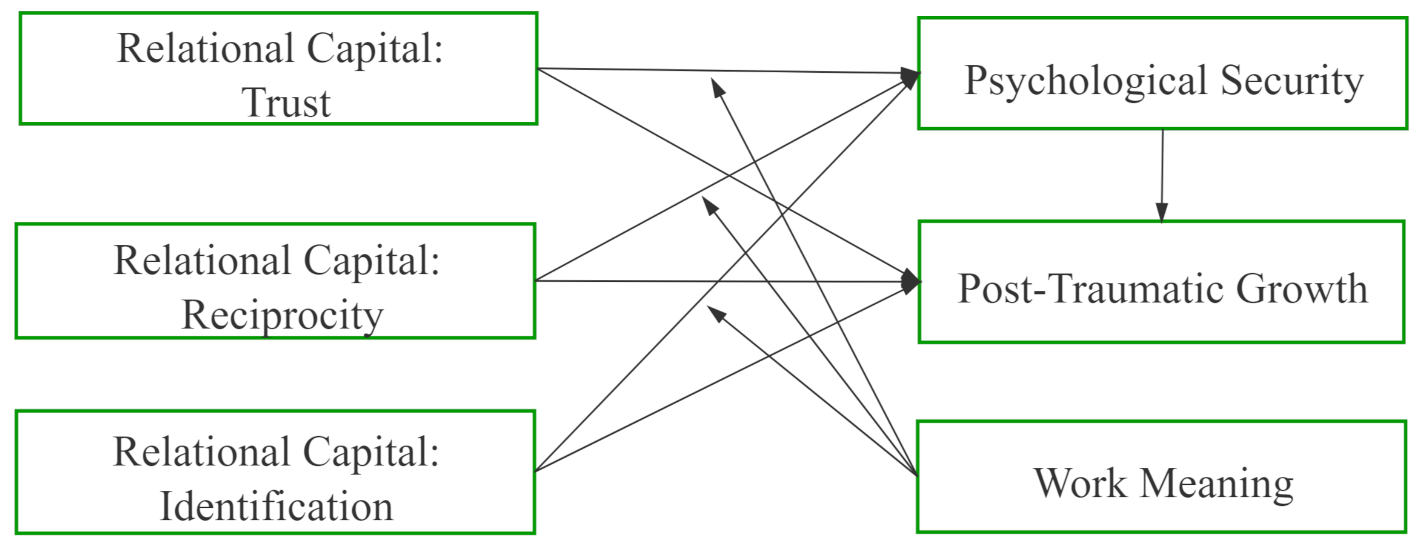

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. The Impact of Relational Capital on Employee’s Psychological Security

2.2. The Mediating Role of Psychological Security

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Work Meaning

3. Research Design

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Measurement

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Mediating Effect

4.4. Moderating Effect

5. Conclusions and Discussions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TRU | Trust |

| REC | Reciprocity |

| IDE | Identification |

| PS | Psychological Security |

| PTG | Post-Traumatic Growth |

| WM | Work Meaning |

References

- Dozois, D.J. Anxiety and depression in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2021, 62, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzi, S.; La Torre, A.; Silverstein, M.W. The psychological impact of preexisting mental and physical health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, S.; Huang, Y.; Chang, C.H.D. Supporting interdependent telework employees: A moderated-mediation model linking daily COVID-19 task setbacks to next-day work withdrawal. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, N. Tackling the negative impact of COVID-19 on work engagement and taking charge: A multi-study investigation of frontline health workers. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S. What Doesn’t Kill Us: The New Psychology of Posttraumatic Growth; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karanci, A.N.; Erkam, A. Variables related to stress-related growth among Turkish breast cancer patients. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2007, 23, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andel, S.A.; Shen, W.; Arvan, M.L. Depending on your own kindness: The moderating role of self-compassion on the within-person consequences of work loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. Active Social Capital: Tracing the Roots of Development and Democracy; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, A.; Hendriks, P.; Romo-Leroux, I. Knowledge sharing and social capital in globally distributed execution. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersema, M.F.; Nishimura, Y.; Suzuki, K. Executive succession: The importance of social capital in CEO appointments. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 1473–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batjargal, B. Internet entrepreneurship: Social capital, human capital, and performance of Internet ventures in China. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.E.; Ouyang, T.H.; Pan, S.L. The role of feedback in changing organizational routine: A case study of Haier, China. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, B.; Donate, M.J.; Guadamillas, F. Inter-organizational social capital as an antecedent of a firm’s knowledge identification capability and external knowledge acquisition. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1332–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang Yu-Hong, J.M.Y. Relationship, social capital and innovations of small- and micro-enterprises. Sci. Res. Manag. 2018, 39, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Inkpen, A.C.; Tsang, E.W. Social capital, networks, and knowledge transfer. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reber, A.S. The Penguin Dictionary of Psychology; Penguin Press: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, C.; Lijuan, A. Developing of security questionnaire and its reliability and validity. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2004, 18, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Aranzamendez, G.; James, D.; Toms, R. Finding antecedents of psychological safety: A step toward quality improvement. In Nursing Forum; Wiley Online Library: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 50, pp. 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, B.; Leather, P. Levels and consequences of exposure to service user violence: Evidence from a sample of UK social care staff. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2012, 42, 851–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Gittell, J.H. High-quality relationships, psychological safety, and learning from failures in work organizations. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2009, 30, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemsen, E.; Roth, A.V.; Balasubramanian, S.; Anand, G. The influence of psychological safety and confidence in knowledge on employee knowledge sharing. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2009, 11, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 1996, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoff-Bulman, R. Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events: Applications of the schema construct. Soc. Cogn. 1989, 7, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, S.; Nelson, K.; Corbo-Cruz, N. Adolescent perceptions on the impact of growing up with a parent with a disability. Psychology 2015, 5, 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnevsky, T.; Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; Demakis, G.J. Gender differences in self-reported posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Women Q. 2010, 34, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroevers, M.J.; Teo, I. The report of posttraumatic growth in Malaysian cancer patients: Relationships with psychological distress and coping strategies. Psycho-Oncology 2008, 17, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Armstrong, D. Trauma type and posttrauma outcomes: Differences between survivors of motor vehicle accidents, sexual assault, and bereavement. J. Loss Trauma 2010, 15, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milam, J.E.; Ritt-Olson, A.; Unger, J.B. Posttraumatic growth among adolescents. J. Adolesc. Res. 2004, 19, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, S.; Eshel, Y.; Zysberg, L.; Hantman, S.; Enosh, G. Sense of coherence and socio-demographic characteristics predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms and recovery in the aftermath of the Second Lebanon War. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.; Leigh, T.W. A new look at psychological climate and its relationship to job involvement, effort, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.W.; Velthouse, B.A. Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 666–681. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, E.; Au-Yeung, B. Relationship between organizational climate and empowerment of nurses in Hong Kong. J. Nurs. Manag. 2002, 10, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Chen, Z.X. Leader–member exchange in a Chinese context: Antecedents, the mediating role of psychological empowerment and outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henderson, D.J.; Liden, R.C.; Glibkowski, B.C.; Chaudhry, A. LMX differentiation: A multilevel review and examination of its antecedents and outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tian, B.; Shi, K. Transformational Leadership and Employee Work Attitudes: The Mediating Effects of Multidimensional Psychological Empowerment. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2006, 38, 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.M.; Hsu, M.H.; Wang, E.T. Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 1872–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | df | /df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Six-Factor Model | 230.722 | 125 | 1.846 | 0.987 | 0.992 | 0.018 |

| Five-Factor Model | 347.659 | 131 | 2.654 | 0.975 | 0.983 | 0.020 |

| Four-Factor Model | 450.671 | 135 | 3.338 | 0.965 | 0.975 | 0.036 |

| Three-Factor Model | 731.929 | 136 | 5.382 | 0.934 | 0.953 | 0.057 |

| Single-Factor Model | 2646.192 | 129 | 20.513 | 0.722 | 0.790 | 0.076 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.84 | 0.370 | ||||||||||

| Age | 1.51 | 0.740 | −0.262 ** | |||||||||

| Education | 2.07 | 0.575 | −0.297 ** | 0.360 ** | ||||||||

| Position | 1.76 | 0.427 | 0.512 ** | −0.465 ** | −0.585 ** | |||||||

| Tenure | 1.95 | 1.009 | −0.183 ** | 0.831 ** | 0.290 ** | −0.324 ** | ||||||

| TRU | 3.86 | 0.858 | 0.010 | −0.170 ** | −0.100 ** | 0.168 ** | −0.146 ** | |||||

| REC | 4.08 | 0.747 | 0.013 | −0.159 ** | −0.091 * | 0.157 ** | −0.130 ** | 0.713 ** | ||||

| IDE | 3.85 | 0.789 | −0.039 | −0.047 | −0.099 ** | 0.142 ** | −0.045 | 0.616 ** | 0.533 ** | |||

| PS | 4.02 | 0.726 | −0.070 | −0.031 | −0.030 | 0.068 | −0.028 | 0.518 ** | 0.565 ** | 0.493 ** | ||

| PTG | 3.98 | 0.723 | −0.023 | −0.127 ** | −0.085 * | 0.147 ** | −0.103 ** | 0.539 ** | 0.555 ** | 0.494 ** | 0.719 ** | |

| WM | 3.93 | 0.813 | −0.035 | −0.178 ** | −0.135 ** | 0.164 ** | −0.181 ** | 0.590 ** | 0.531 ** | 0.607 ** | 0.674 ** | 0.641 ** |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Mdoel 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTG | PS | PTG | PTG | PS | PTG | PTG | PS | PTG | |

| Gender | −0.156 * | −0.171 * | −0.053 | −0.165 | −0.174 * | −0.061 | −0.123 | −0.136 | −0.039 |

| Age | −0.020 | 0.057 | −0.054 | −0.012 | 0.068 | −0.052 | −0.094 | −0.018 | −0.083 |

| Education | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.008 | −0.001 | 0.031 | 0.035 | 0.009 |

| Position | 0.160 * | 0.097 | 0.102 | 0.168 | 0.096 | 0.111 | 0.140 | 0.072 | 0.095 |

| Tenure | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.003 | −0.005 | −0.008 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.004 |

| TRU | 0.440 *** | 0.442 *** | 0.176 *** | ||||||

| REC | 0.521 *** | 0.552 *** | 0.192 *** | ||||||

| IDE | 0.438 *** | 0.447 *** | 0.160 *** | ||||||

| PS | 0.601 *** | 0.596 *** | 0.624 *** | ||||||

| 0.229 *** | 0.277 *** | 0.562 *** | 0.317 *** | 0.328 *** | 0.558 ** | 0.259 *** | 0.247 *** | 0.554 *** | |

| F | 53.487 | 48.030 | 138.079 | 58.312 | 61.331 | 135.575 | 43.294 | 41.113 | 133.626 |

| Moderating Effect | Moderated Mediating Effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Effect | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | Effect | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | |||||

| TEU | 0.1052 | 0.0324 | 0.0416 | 0.1678 | 0.0456 | 0.0192 | 0.0084 | 0.0839 |

| 0.2386 | 0.0394 | 0.1612 | 0.3159 | |||||

| REC | 0.0706 | 0.0375 | −0.0030 | 0.1442 | 0.0434 | 0.0218 | 0.0005 | 0.0867 |

| 0.1919 | 0.0425 | 0.1086 | 0.2763 | |||||

| IDE | 0.0521 | 0.0317 | −0.0101 | 0.1143 | 0.0309 | 0.0228 | −0.0162 | 0.0738 |

| 0.0762 | 0.0260 | 0.0253 | 0.1272 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nie, T.; Tian, M.; Liang, H. Relational Capital and Post-Traumatic Growth: The Role of Work Meaning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147362

Nie T, Tian M, Liang H. Relational Capital and Post-Traumatic Growth: The Role of Work Meaning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(14):7362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147362

Chicago/Turabian StyleNie, Ting, Mi Tian, and Hengrui Liang. 2021. "Relational Capital and Post-Traumatic Growth: The Role of Work Meaning" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 14: 7362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147362

APA StyleNie, T., Tian, M., & Liang, H. (2021). Relational Capital and Post-Traumatic Growth: The Role of Work Meaning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7362. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147362